Murder at Algiers Motel

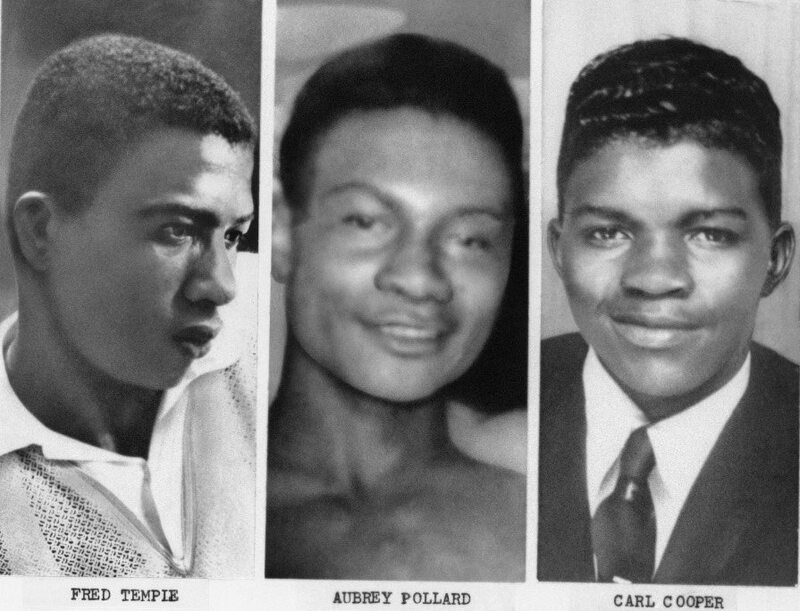

On July 26, the fourth day of the Uprising, three white police officers murdered three innocent African American teenagers at the Algiers Motel. The DPD officers were part of a contingent of ten policemen and National Guardsmen who stormed the motel and then brutalized and tortured the interracial group of youth they found inside. Their cover-up of the incident ultimately unraveled, but none of the perpetrators was convicted. Carl Cooper, Aubrey Pollard, and Fred Temple lost their lives.

Snipers?

It all began with a starter pistol. At least, that's the story according to Juli Hysell and Karen Malloy. Hysell and Malloy were two young white females who were inside the Algiers Motel with Carl Cooper, Michael Clark, Lee Forsythe, Auburey Pollard, and James Sortor, five young African American males, on the evening of July 25, 1967.

Most of the black youth were members of a music group, the Dramatics, and either worked at Ford Motor Company or had recently been laid off from the automaker. The two white females, Hysell and Malloy, were subsequently convicted on prostitution charges. The Algiers Motel was a known location for narcotics trafficking and sex work, frequently raided by the precinct vice squad. That night, the interracial group of youth were hanging out and seeking a refuge from the chaos engulfing the city.

The scene was originally relaxed. As Hysell later testified, Carl Cooper "had a record player . . . and asked us if we wanted to listen to some records." The two females went with Carl and his friend Lee Forsythe up to their room, #A-14. About 15 minutes later, according to Juli Hysell, "Carl Cooper pulled a pistol out from under the bed. Cooper and Forsythe were playing with it. They had blanks in it, and Cooper shot it twice." Nobody's life was in danger. The gun was a starter pistol, used in track competitions, or, as Hysell described it, "a pellet gun or something, just looked like a plastic gun to me. . . . It wasn’t a real gun."

Interestingly, Lee Forsythe denied that his friend Carl had the starter pistol at that time. He later testified, "not while I was there, no. . . . I saw a blank cap pistol earlier, that day, I didn’t see any gun that night." James Sortor, who was not in the room, said that Carl came downstairs at one point and fired the blanks at him and Aubrey Pollard, as a joke, as if it were a real gun. The truth of what actually happened is not known, and the specific details are also not important, except that reports of gunfire caused a contingent of DPD officers and National Guardsmen to open fire into, and then storm, the Algiers Motel.

Outside, a National Guard warrant officer, Theodore Thomas, phoned in a report to the Detroit Police Department that "he and his men were being fired upon." Based on the sound of shots alone, Thomas and his unit began firing into the Algiers Motel and also shooting out the streetlights in the area.

Forensic evidence later confirmed that at no point did anyone inside the Algiers Motel fire any gunshots toward the street.

Enter the DPD

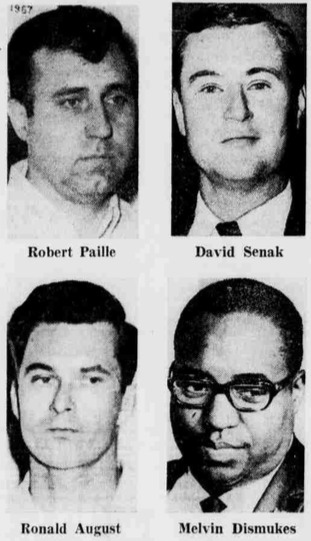

Three DPD patrolmen--David Senak, Ronald August, and Robert Paille--were among the law enforcement officials who responded to the reports of a sniper attack from inside the Algiers Motel. They also led the raid into the building and are the three officers most directly involved in the murders of Carl Cooper, Aubrey Pollard, and Fred Temple.

A contingent of DPD officers, Michigan State Police, National Guardsmen, and even a private security guard working nearby responded to the sniper fire alert. There was no clear chain of command. All of the law enforcement officials were white; the security guard, Melvin Dismukes, was African American.

Shortly after midnight, the law enforcement contingent began to direct concerted gunfire into the Algiers Motel and then stormed the building. Everything that precipitated the raid and that occurred inside is contested and subject to competing memories and the partial vantage points of a chaotic situation, not least the clear incentive for the law enforcement officials to lie to cover up their actions.

As a policy matter, it is worth emphasizing that the police officers' actions at the Algiers Motel violated the DPD's "Riot Control Plan." Its protocols included: "when rioters or snipers are barricaded in a building, chemical agents should be used through windows or doors. . . . The use of tear gas is an effective and humane method of riot control."

Instead, the DPD officers who arrived on the scene immediately began shooting into the building, joining the National Guardsmen who were already firing their weapons, and resulting in at least 200 rounds fired in a 10-15 minute time span. The teenagers inside were panicking and taking cover wherever possible.

The law enforcement contingent, including members of the Michigan State Police and National Guard, entered the building and spread most of the teenagers up against the wall. The situation was extremely violent, and they were striking the teenagers with their rifle butts and otherwise beating and brutalizing them, in theory trying to identify the "sniper." They officers used many racial slurs and called the two white females "n----- lovers." They also stripped the two white females. Michael Clark, one of the African American males, recounted:

Murder

Carl Cooper, 17 years old, died first, during or possibly before the mass interrogation in the lobby area. Cooper's body was found in room #A-2. The evidence indicates that Patrolman David Senak shot and killed Carl Cooper that night. Witnesses claim that they heard Cooper say, "take me to jail, I don't have any weapon," right before the gunshot, and that a law enforcement officer yelled out, "I already killed one of them." There is another theory, that Cooper was killed in the initial assault on the building, which the Wayne County prosecutor cited to clear Senak and others present in Cooper's death.

Fred Temple, 18 years old, died next. Patrolman Robert Paille later told investigators that "I shot one of the other men," clearly meaning Temple, and that Patrolman Senak "shot almost simultaneously." (Paille's statement was later ruled inadmissible in court because of alleged improprieties in the Homicide investigation).

The interrogations, beatings, and torture in the lobby continued for a long time. Lee Forsythe specifically accused Patrolman Senak of being the most aggressive:

At some point, the police officers began pulling each of the African American teenagers into separate rooms, in theory to ask them about the alleged sniper weapon. When they denied that such a weapon existed, the officers beat them more. The State Police left the building during these events, apparently not wanting to be involved further.

Then the officers escalated the situation with a "death game." Patrolman Senak asked Theodore Thomas, the National Guard warrant officer, if he "wanted to kill one" and "wanted to shoot a n-----." Thomas took Michael Clark into a room and fired a shot into the ceiling, in order to scare the other youth into confessing. The same thing happened with Roderick Davis. These and other black youth were also beaten and required medical treatment afterward.

Then DPD Patrolman Ronald August took Aubrey Pollard, 19 years old, into a third room. The coroner reported that Pollard was shot and killed while either lying on the floor or in a kneeling position. Patrolman August admitted shooting Pollard to Homicide investigators but later amended his statement, after facing charges, claiming it was in self-defense because the teenager lunged at him. All available evidence contradicts the self-defense claim.

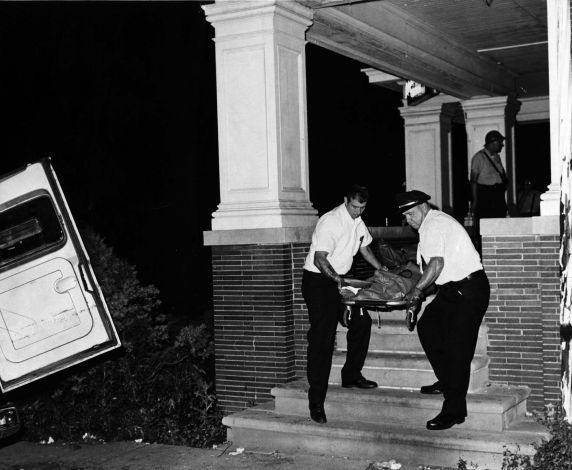

After Patrolman August executed Aubrey Pollard, the DPD officers and their colleagues began to clear out the motel. The survivors were told to "get out of here, because I don’t want to see you get killed like the rest of them."

Cover Up and Justice Denied

The DPD officers--David Senak, Ronald August, and Robert Paille--covered up the murders and did not even mention the deaths of three civilians in their report of the incident. The DPD did not learn about the fatalities until the clerk at the Algiers Motel called the morgue to report three bodies.

The autopsy revealed that all three teenagers had been shot from close range and were in "non-aggressive postures" when they died.

On July 30, four days after the event, the three DPD officers filed a false report saying that they discovered three wounded civilians in the motel, called for an ambulance, and left before it arrived. A few days later, Patrolmen August and Paille admitted their direct involvement in the killings to Homicide detectives, and Paille also implicated Patrolman Senak in Fred Temple's death. (These confessions were either ruled inadmissable or amended to include self-defense claims that juries believed).

In the aftermath, the families of the three deceased teenagers filed a civil rights complaint with the Department of Justice, and black radicals held a mock trial to convict the officers. An investigation by the Detroit Free Press also helped forced local officials and the Wayne County prosecutor to act.

In August 1967, Prosecutor William Cahalan filed charges against Officer Robert Paille, for the murder of Fred Temple, and against Officer Ronald August, for the murder of Aubrey Pollard. These were the only felony charges filed against any DPD officers for the fatalities of civilians during the 1967 Uprising, since Cahalan ruled all other killings to be justifiable homicides. These were also the only felony charges filed against any DPD officers for the homicides of any civilians over a several decade time span. The Detroit Police Officers Association union provided the legal defense for the officers as part of its hardline defense of all police officers against all brutality allegations and criminal charges in the late 1960s and 1970s.

In fall 1967, the Wayne County prosecutor also brought conspiracy charges against Senak, Paille, August, and Melvin Dismukes, the African American security guard, for their role in the broader event, including the physical abuse of the survivors. A local judge dismissed the case after slandering the victims as "unemployed Negroes" and citing the warlike atmosphere of the riot.

In 1968, a state judge dismissed the murder charge against Robert Paille, ruling that his statement that he killed Fred Temple was inadmissable.

In 1969, an all-white jury acquited Ronald August of the murder of Aubrey Pollard, believing his claim of self-defense and his description of Detroit in July 1967 as a "full scale war" with police officers operating as "soldiers in the battlefield."

John Hersey's blockbuster expose, The Algiers Motel Incident (1968), raised even more public awareness about the DPD's gross abuse of power and contributed to the pressure on the federal government to intervene.

In 1970, the U.S. Department of Justice brought charges against the three white officers, and the black security guard who joined the raid, for conspiracy to violate the civil rights of the occupants of the Algiers Motel. An all-white jury acquitted them of these charges.

The city of Detroit paid small settlements after the families of the three teenagers filed civil lawsuits.

The Detroit Police Department rehired Ronald August and David Senak in 1971, after firing them in the aftermath of the Algiers Motel killings. The DPD refused to rehire Robert Paille, citing the false statements he made in his initial incident report, even though August and Senak had also made the same false statements. The DPD also rehired Senak despite the overwhelming evidence that he was the ringleader of the torture and brutality of the youth inside the Algiers Motel, and despite the fact that he had admitted killing two other African Americans in separate, suspicious circumstances during July 1967.

Sources:

Tony Spina Photographs, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Detroit News Collection, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

John Hersey, The Algiers Motel Incident (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1968)

Sidney Fine, Violence in the Model City: The Cavanagh Administration, Race Relations, and the Detroit Riot of 1967 (Lansing: Michigan University Press, 2007)

Danielle L. McGuire, "Detroit Police Killed their Sons at the Algiers Motel," Bridge (July 25, 2017), https://www.bridgemi.com/urban-affairs/detroit-police-killed-their-sons-algiers-motel-no-one-ever-said-sorry