2. Youth Criminalization

The Detroit Police Department, through both its formal policies and its unofficial practices, intensified the criminalization of African American youth in the late 1960s and early 1970s. After the July 1967 Uprising, most investigations had attributed the civil disorder to the criminality and anti-social hostility of African American teenagers and young adults, while differing on the degree to which police brutality and underlying forces such as inner-city unemployment and racial discrimination had caused the disturbances. While the Kerner Commission placed ultimate responsibility on "white racism," the Detroit Police Department and the majority of white Detroit residents rejected this analysis and instead called for an even tougher crackdown on African American youth whom they labeled as criminals, radicals, and anti-social juveniles. The city of Detroit's passage of a stop-and-frisk law in the summer of 1968, with the open understanding that the DPD would apply it aggressively in poor African American neighborhoods and against black youth in public spaces, symbolized the full-blown criminalization of African American youth during the "law and order" politics of the late 1960s. The federal government's launching of a war on crime in the mid-1960s, and then a war on drugs a few years later, also channeled funding and resources to militarized get-tough policing in Detroit and other urban centers.

The criminalization of African American youth was about far more than aggressive, "get-tough," crime control. During the late 1960s and early 1970s, the overwhelmingly white DPD consistently criminalized black youth in pursuit of its political objectives of maintaining racial segregation and suppressing civil rights activism and radical political dissent. The DPD operated as an extension of the segregationist white majority in the city of Detroit, which continued to aggressively defend white neighborhoods and schools in the face of rapid demographic transition that had brought the city population to the brink of a black majority by the end of the decade. Many white residents defended police brutality as necessary to control the 'criminal' black population and viewed the stop-and-frisk law, in particular, as critical to maintaining the police department's discretionary authority to monitor and contain African American youth inside their own ghetto communities and ensure the 'safety' of so-called 'law-abiding' white neighborhoods. The police department deployed stop-and-frisk tactics with particular aggression along the racial boundaries between black and white neighborhoods.

The pages in this section document the criminalization of black youth, and in one case of countercultural white youth, in four general areas or specific incidents. This list does not include the unprovoked DPD assault on young civil rights activists in the 1968 Poor People's Campaign, which will be covered later.

- School Criminalization: Between 1968 and 1971, the DPD intervened with force and brutality when African American students engaged in civil rights and black power protests, especially inside the senior and junior high schools. The DPD further criminalized black students first and foremost when white students and community members attacked them in newly integrated schools, especially those located in the mostly white sections of Northwest and Northeast Detroit.

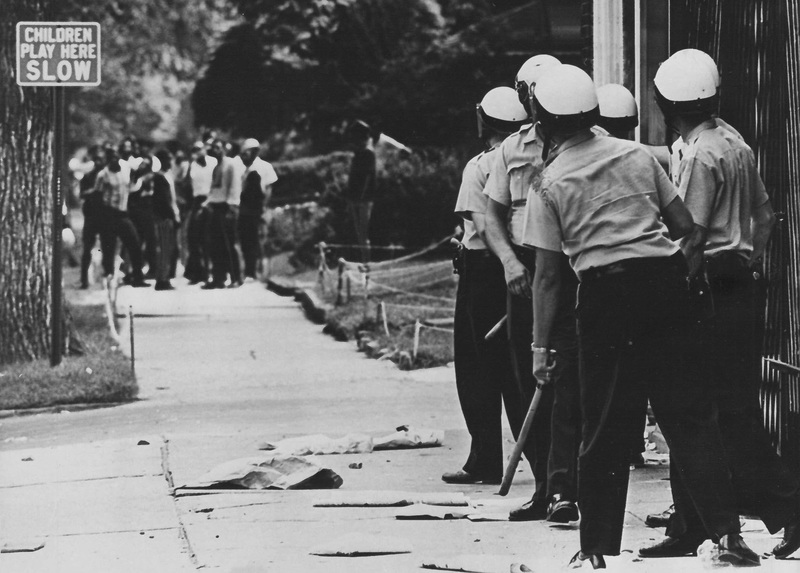

- Neighborhood Criminalization: The DPD harassed, persecuted, and brutalized members of an African American youth club that was located in a black enclave surrounded by segregated white neighborhoods in Northwest Detroit during the year after the July 1967 Uprising.

- Off-Duty Criminalization: In the Veterans Memorial Incident of November 1968, dozens of drunken off-duty white police officers brutally attacked, and fired guns at, African American teenagers attending a church youth dance.

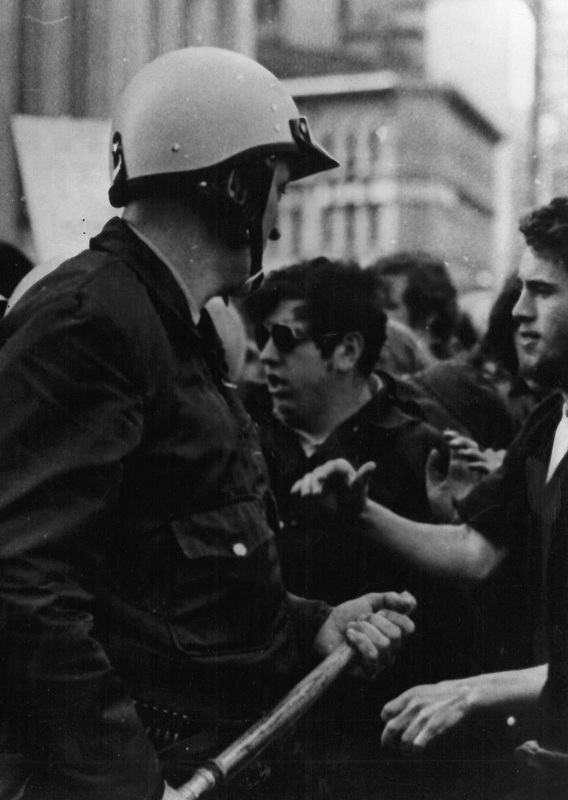

- Countercultural Criminalization: The Balduck Park Incident of 1970, a militarized police assault on white youth who were congregating in public space, revealed the extreme brutality that "riot control" police were eager to deploy against political and cultural dissidents of all races.

Youth Criminalization as Public Policy

DPD officers enjoyed almost unlimited discretion to criminalize youth on the streets, in their cars, in their schools, and in other public spaces. Under state law, police officers could detain juveniles for essentially any reason and did not need to pretend to adhere to the "probable cause" or even "reasonable suspicion" that due process protections theoretically guaranteed to adult citizens. The juvenile justice system processed most youth on a separate track, with investigations by social workers into the circumstances of their "delinquency" and disciplinary decisions by juvenile court judges that rarely could be appealed. In this system of comprehensive discretion, the DPD criminalized African American youth in particular by focusing more on the public order than on the criminal conduct side of "law and order." Selective enforcement of discretionary authority against youth was the most discriminatory feature of the entire criminal-legal system.

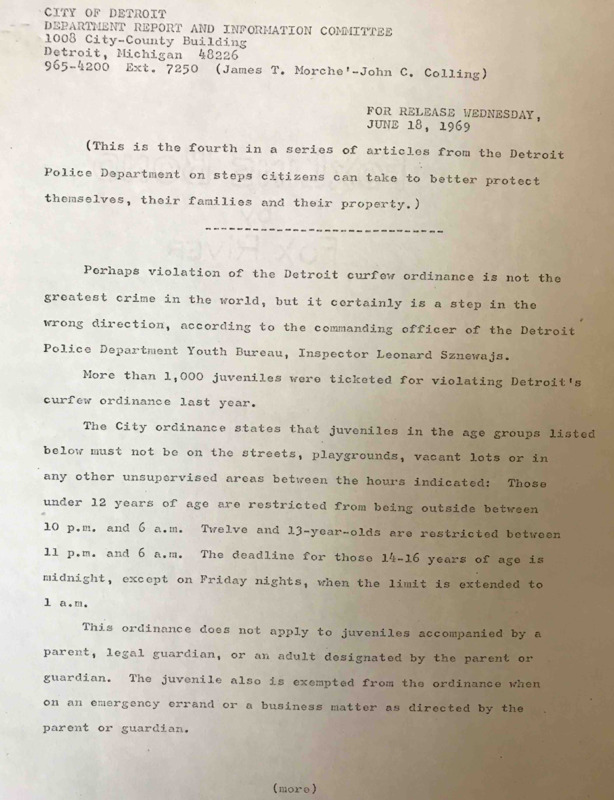

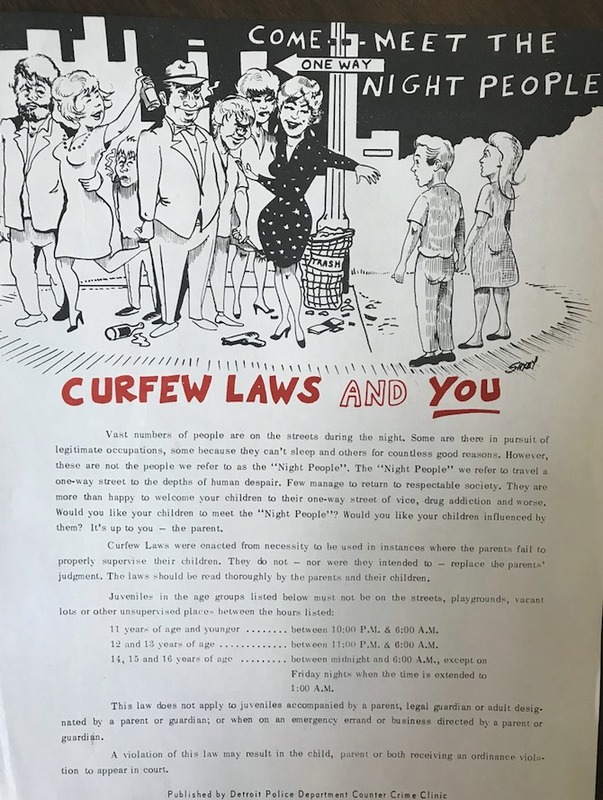

The municipal curfew, for example, was a "public safety" law that explicitly discriminated against all youth based on their status, meaning their age, rather than on actual criminal conduct. Curfew regulations, as deliberately designed, enabled police to exercise discretionary criminalization and, inevitably, to enforce the policy in highly selective and discretionary ways based on race, economics, gender, geography, and other variables. During 1968, the DPD ticketed more than 1,000 juveniles for violating the city of Detroit's curfew ordinance, although the number of youth who violated curfew was of course far, far higher. Juveniles between the ages of 14 and 16 who were not accompanied by their parents or guardians could be arrested and cited if on the streets or "in any other unsupervised areas" after 11 p.m., six nights a week, and after 1:00 a.m. on Friday evenings. Younger children had earlier curfews, depending on their age. Juveniles under age 17 were also barred completely from entering pool halls, and specific curfew restrictions applied to bowling alleys, theaters, and other public amusements. They could not attend dances without parents or chaperones unless the police department had specifically granted a permit. The DPD Youth Bureau warned teenagers that any "objectionable noise and disorderly conduct" in public parks could result in a loitering citation. DPD officers selectively enforced these policies, especially in African American neighborhoods and commercial districts but also increasingly against white "hippies" and other countercultural youth as their subculture expanded in the late 1960s. Read the DPD's full list of youth regulations in the gallery below.

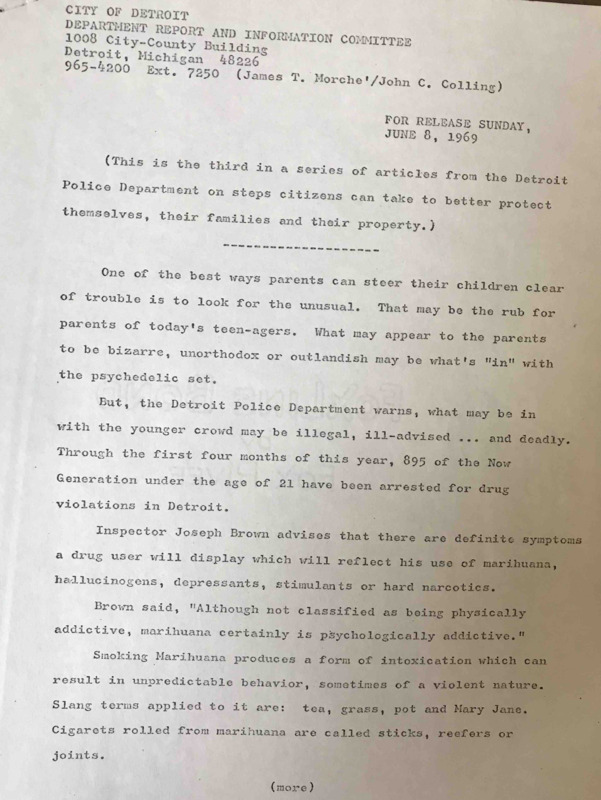

Although the DPD's policies of youth criminalization primarily targeted black neighborhoods, the police also cracked down on particular groups of white youth in the late 1960s and early 1970s, especially "hippie" rebels associated with the counterculture and radical activists in the New Left and anti-Vietnam War movements (these categories often overlapped). While New Left activists were most concentrated on university campuses, and countercultural radicals clustered in bohemian urban enclaves, both political movements also had a significant following among white high school and some junior high students during this time period. In 1969, along with its curfew warning, the DPD released a report about the growing illegal drug crisis among the "psychedelic set," which was a euphemism for white hippies (below, second from right). The DPD warned parents that thousands of youth had been arrested on drug charges and focused in particular on the dangers of marijuana and LSA, the psychedelic drugs popular in the white counterculture. Like the Nixon administration, the DPD warned that recreational use of marijuana would lead youth to a life of heroin addiction and crime.

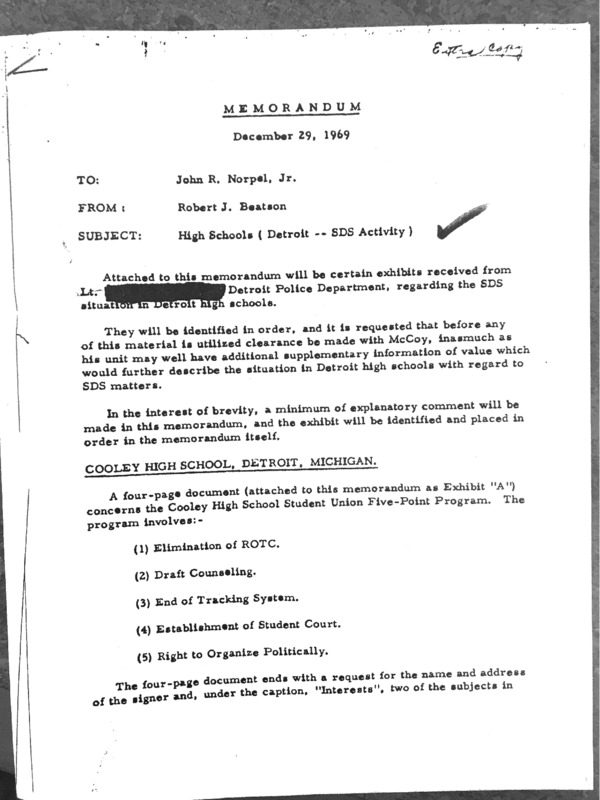

The DPD also targeted radical youth political activists of all races through its top-secret political surveillance unit, the Intelligence Bureau, which routinely engaged in illegal activities by monitoring and spying on left-wing and racial justice organizations. While most of the Intelligence Bureau activities concentrated on black power organizations and white New Left groups, especially those active in the campaign against the Vietnam War, police surveillance also monitored teenage activists and radicals in the city's public high schools. The DPD Intelligence Bureau's report on youth radicalism in Detroit high schools in December 1969, reproduced below right, focused most on black power activists and on the white antiwar radicals in Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). The DPD reported that the SDS chapter at Cooley High School, which had a strong black power movement during this time period, sought to eliminate military ROTC training, end draft counseling, and encourage students to "organize politically." The DPD Intelligence Bureau also provided a thorough account of the political activities of the black power movement at Northern High School, including analysis of articles from its underground newspaper. Nothing described in this report was illegal, and every single activity fell under the category of constitutionally protected speech or freedom of assembly, even more evidence that the DPD so often criminalized youth for their political beliefs and actions rather than for actual law-breaking.

Sources:

Detroit Police Department Additional Papers (1965-1993), Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library

Fifth Estate Records, Joseph A. Labadie Collection, Special Collections Library, University of Michigan