Black Officers and DPD Discrimination

The Detroit Police Department had a long history of racial discrimination and exclusion in its hiring and promotion practices. Civil rights organizations, led by the Detroit Urban League, had for decades maintained pressure on the DPD to discontinue its discriminatory policies by integrating the force and promoting more black officers to leadership positions. The small number of African American officers hired before the late 1960s also faced extreme prejudice from many of their white counterparts on the job and systematic racism from the department as a whole. Civil rights groups and liberal police reformers considered a racially diverse and better trained police force to be the key to improving police-community relations and curbing the epidemic of law enforcement brutality against black citizens. Black police officers also became increasingly involved in civil rights politics during the late 1960s and early 1970s, especially through their Guardians of Michigan association, which advocated for affirmative action and became a strong critic of police brutality and indiscriminate deadly force against African American citizens, as detailed in the final section on this page.

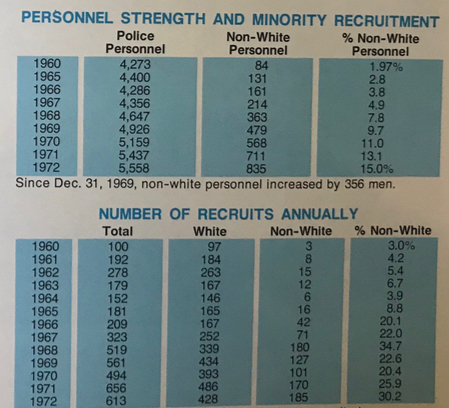

After the 1967 Uprising, the overwhelmingly white nature of the DPD became part of a broader legitimacy crisis for law enforcement, and even conservative police executives recognized that the situation had to change. During the final three years of the Cavanagh administration, under a liberal white mayor who strongly supported affirmative action to diversify the force, the number of black officers doubled as the DPD slowly increased from 5% to 10% nonwhite. (Police integration in the almost all-male department focused on race and not gender during this era, and official efforts to bring more women into the DPD did not happen until after Coleman Young's election in 1973). Despite the Cavanagh adminstration's public commitment to increased diversity, civil rights organizations and government agencies such as the Detroit Commission on Community Relations and the Michigan Civil Rights Commission accused the DPD of overt racial discrimination in hiring and promotion during the late 1960s. These civil rights groups demanded a comprehensive affirmative action program to ensure that half of all new officers were nonwhite, with the ultimate goal of achieving a 50-50 racial ratio that would reflect the makeup of the city's population. Despite some real improvements, this never came close to happening while the city government and police department remained under white leadership.

Diversity and Discrimination during the Gribbs-Nichols Administration

Mayor Roman Gribbs, a law-and-order conservative, expressed support for increasing the levels of black officers and promoting more black executives after he took office in 1970. Police Commissioner John Nichols, appointed by Gribbs to lead a crackdown on street crime, denied that the department's hiring and promotion practices were discriminatory but did make a public commitment to "attract and maintain qualified black officers," although he opposed the use of quotas to do so. The nonwhite makeup of the police department as a whole expanded from 10% to 15% during the first three years of the Gribbs mayoralty, including 4,723 white personnel and 835 nonwhite employees (see chart). The number of black patrolmen was somewhat higher, around 19% of the total by 1972. Between one-quarter and one-third of annual recruits during the Gribbs-Nichols administration were nonwhite, which was no better than during the second term of the Cavanagh administration and well below the majority-black population of the city of Detroit by the early 1970s. The DPD under Nichols, and his replacement Phillip Tannian, did elevate several African American officers to senior leadership positions and publicized their roles aggressively to demonstrate its commitment to racial diversity and equal opportunity (right).

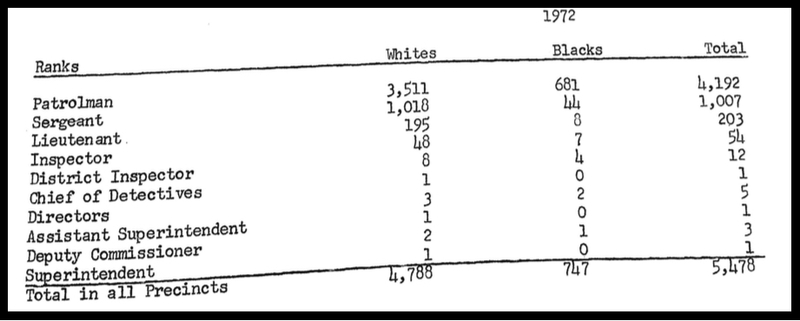

The Detroit Urban League assessed the successes and failures of the DPD's promise to diversify the force and eradicate discriminatory practices in a major report released in the fall of 1972 (gallery below left). The DUL praised the police department for making some gains, especially in elevating a number of black officers to the top leadership ranks, but also emphasized that "there needs to be more progress." The DPD routinely rejected more than 90% of job applicants, and civil rights groups had long contended that the department's written examination was culturally biased and its discretionary evaluation process was racially discriminatory. The DUL investigation showed that in 1971, the DPD had rejected 3,455 of 3,625 African American applicants as unqualified and had accepted white applicants at more than twice the rate of their black counterparts. In other words, if the same percentage of black and white applicants were admitted to the Police Academy, each new class of officers would represent the 50-50 ratio that the city government and police hierarchy claimed to be the goal.

The DUL investigation also revealed that, despite some improvement in promotion policies, most African American officers continued to occupy the entry-level position of patrolman and to be passed over for supervisory positions that brought more authority and higher pay (see chart). Only 12% of black officers held a rank above patrolman, including 52 with the position of either sergeant or lieutenant. By contrast, 27% of white officers held a rank above patrolman, including 1,213 sergeants and lieutenants. Black officers were actually somewhat better represented in the upper ranks of the DPD leadership than in the street-level supervisory roles, occupying 14 of the 78 positions ranging from precinct inspector to administrators at the central headquarters. White officers dominated at all ranks of the most prestigious bureaus and special operations units, such as Homicide, Narcotics, the Tactical Mobile Unit, and STRESS.

The DPD consistently denied that its application and promotion processes were racially discriminatory, despite the considerable evidence compiled by civil rights groups that just as consistently rejected these claims. In the area of affirmative action, new federal oversight policies and court decisions in the early 1970s also made it clear that the city of Detroit's approach was vulnerable to class-action litigation and almost certainly inadequate as a matter of equal protection law. Francis Kornegay, the executive director of the Detroit Urban League, informed Mayor Gribbs in a letter accompanying the investigative report that its evidence constituted "prima facie discrimination in hiring" (gallery, second from left). Kornegay urged the mayor to adopt "an Affirmative Action program which is comprehensive, progressive and enforceable." To assist in this effort, the DUL devised an affirmative action plan for the targeted recruiting and training of African American applicants, in advance of the written exam and evaluation process, in order to increase the acceptance rate (gallery, below right). As always, the Detroit Urban League argued that the hiring and promotion of black officers would "be a vital force in changing the low image of the police department in the black community, which is needed to improve the police-citizens cooperative relationship in Detroit."

Map of Racial Breakdown of Black and White Officers at DPD Precinct Stations in 1972

The interactive map below contains the number of Black and white officers at each DPD precinct station, based on the Detroit Urban League's 1972 report (gallery above, left). Note that the 3rd, 8th, and 9th precincts had been eliminated in a prior consolidation. The small percentage of Black officers in the 1st and 5th precincts is particularly notable, since those stations policed the racial boundary lines surrounding the downtown/midtown business corridor and on the East Side (the 1st precinct was located in the same building as DPD headquarters).

The Lives and Politics of Black Officers

Black police officers continued to face substantial discrimination within the DPD during the early 1970s, and in response they mobilized politically in unprecedented ways to fight against racism within the department and to protest systemic brutality against African American citizens. At least 250 black officers in Detroit belonged to the Guardians of Michigan, a statewide organization of African American officers that was part of a broader Guardians network with chapters in other large cities around the nation. The Guardians of Michigan first formed in the late 1960s as a counterpoint to the Detroit Police Officers Association (DPOA), which most black officers considered to be a racist and right-wing union that only represented the interests of white officers and supported brutality and terror against the African American community as a whole. The Guardians joined other civil rights organizations in the first mass protests against STRESS in the fall of 1971 and consistently denounced the unit as a racist and illegal force of repression. Some black officers in Detroit also joined the Concerned Police Officers for Equal Justice, a group that formed in the early 1970s to operate as a political organization that would protect their interests. Isaiah (Ike) McKinnon, a black officer who joined the DPD in 1965 and faced extensive prejudice and discrimination from his white colleagues, stated in an interview with our project that almost all African American policemen viewed the DPOA union as an openly "racist organization" during this era. The Guardians of Michigan pledged to "fight racism" against black officers inside the Detroit Police Department and to speak out against police brutality and misconduct in order to make law enforcement "more effective in controlling and preventing crime" (gallery, below left).

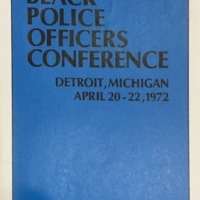

In April 1972, the Guardians of Michigan hosted a national Black Police Officers Conference in the city of Detroit, just a month after the group issued a call for the abolition of STRESS. Speakers at the conference condemned STRESS and similar tactical assault units in other cities as a "more sophisticated" form of police brutality that had also undermined police-community relations and increased rather than decreased crime. Keynote speaker Renault Robinson, the head of the Chicago Afro-American Patrolmen's League, declared that "we're not saying we're against law enforcement, . . . but we're also saying we're going to join the struggle" for civil rights and against police brutality. Another Guardians leader called police officers on the street the "agents of fear and repression" of a completely corrupt criminal justice system. The Black Police Officers Conference resulted in a list of 22 recommendations circulated by the Guardians of Michigan (see gallery, second from left), including:

- Support for a civilian review board to investigate and punish police brutality

- Recruitment of more black police officers

- Forums where Guardians officers interacted with the black community

- Formal coalitions between the Guardians and community-based civil rights groups, especially to resist and expose police brutality

- "Abolishment of STRESS and other such racist units"

White officers attacked the Guardians of Michigan as a political organization that leveled "persistent and irresponsible challenges to the necessary authority" of the DPD, accusations that increased after the Guardians formally joined the anti-STRESS coalition (below right). Such charges ignored the openly political role of the white-dominated DPOA union, which defended white officers against all charges of brutality and misconduct and sued the DPD on multiple occasions to protect them from investigation and discipline. While some black police officers also committed brutality and misconduct against African American citizens and participated in other forms of corrupt law enforcement, the political debate about police violence during this time period operated along a clear racial dividing line between an overwhelming majority of white officers who defended the system of discretion and unaccountability and a vocal contingent of black officers who demanded fundamental changes and expressed open support for civil rights demands.

Black officers experienced significant discrimination on the job and often were targeted for retaliation when they reported or protested brutality and misconduct by white officers. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, black patrolmen consistently charged that the DPD assigned them to the most dangerous beats and the least prestigious precincts and units. Supervisors also generally forced black officers to enter hazardous situations first, especially in cases of reported gunfire, effectively using their bodies as shields for white officers. Black policemen recounted many cases of unprovoked verbal harassment and even physical brutality from their fellow white officers, which the DPD hierarchy and the DPOA union habitually denied and showed no interest in investigating.

The Guardians of Michigan, and the smaller black police association known as the Concerned Police Officers for Equal Justice, protested such racial discrimination within the police department and defended African American officers who sought to bring criminal activity by law enforcement officials to justice. For example, the Guardians of Michigan strongly denounced the DPD's retaliation against Lt. George Bennett, a black officer who sued the department for racial discrimination in 1971 and was reassigned to a less prestigious post. Then Commissioner Nichols placed Lt. Bennett in charge of the investigation of narcotics corruption by DPD officers, which led to an outpouring of harassment from white officers and even anonymous threats on his life. The Guardians of Michigan defended Bennett's inquiry and even provided him with a 24-hour bodyguard as protection against these threats. (For more on this case, see the Pingree Street Conspiracy page later in this section). Mary Jarrett Jackson, a police lab technician and one of the first black women to become a DPD officer, also faced death threats and other harassment after she exposed the criminal misconduct that led to the firing of STRESS officer Raymond Peterson and his (unsuccessful) prosecution for the murder of an African American civilian.

Black police associations also protested the DPD's discriminatory treatment of African American officers who were injured in the line of duty, especially the 1972 case of Donald Kimbrough, examined in detail on the next page.

Sources:

Detroit Urban League Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

Roman S. Gribbs Mayoral Records, Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library

Detroit Police Department Additional Papers (1965-1993), Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library

Detroit Commission on Community Relations/Human Rights Department Records, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Detroit News Photograph Collection, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Detroit Free Press, April 22, 1972, June 25, 1973

Isaiah (Ike) McKinnon Interview, Part 1, December 3, 2019, https://lsa-dss.mivideo.it.umich.edu/media/t/1_rxtil0md/145739741