Commissioner Edwards: Liberal Reform

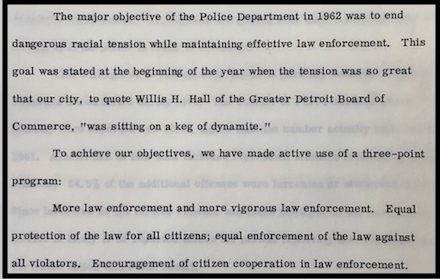

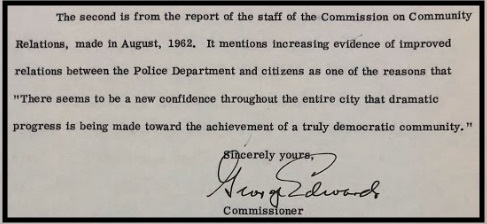

In 1962, Mayor Jerome Cavanagh appointed George Clifton Edwards as police commissioner of the city of Detroit. Edwards, who had previously served as a justice on the Michigan Supreme Court, accepted the position with the goal of easing "dangerous racial tensions" in the city and implementing a liberal reform agenda based on equal law enforcement (right).

African American anger over the DPD's violation of civil rights in the crash program of 1960-1961 had helped to bring the Cavanagh administration to power, but many black residents as well as white believed that crime was a problem that had to be addressed. Commissioner Edwards promised to do so by combining "vigorous law enforcement" with equal treatment under the law, which he believed would encourage more citizens (in particular black citizens) to assist the police department in fighting crime. For this stance, Edwards faced fierce resistance from within the DPD. As one historian writes, "from the outset, the department's top commanders tried to undermine his efforts, seizing every opportunity to discredit him." But he also enjoyed the strong support of Detroit's leading civil rights organizations during his two-year tenure as police commissioner, with the exception of the protests following the police killing of Cynthia Scott in July 1963.

George Edwards was born in Dallas, Texas, in 1914, into a household of liberal activists. His mother was one of the first female graduates of the University of Texas, and his father was a radical attorney who defended civil rights and labor activists. Edwards attended Harvard College during the Great Depression and committed himself to a career fighting poverty and racial oppression. He arrived in Detroit in 1936 as a 22-year-old who embraced socialist politics, worked for the United Auto Workers, and was even arrested twice during protests. During World War II, he briefly headed the Detroit Housing Commission, unsuccessfully pressing for residential integration of low-income projects, and then was elected to the city council. In 1949, he ran for mayor but lost to Albert Cobo, a conservative Republican who openly supporting housing segregation. Edwards received almost all of the African American vote in this losing cause. In 1951, he became a local judge and ultimately ended up on the Michigan Supreme Court before resigning to take the Detroit police commissioner job in 1962. Edwards served as commissioner for two years, before President Kennedy appointed him as a federal appellate judge, the position he held until his death in 1995.

Edwards Reform Agenda

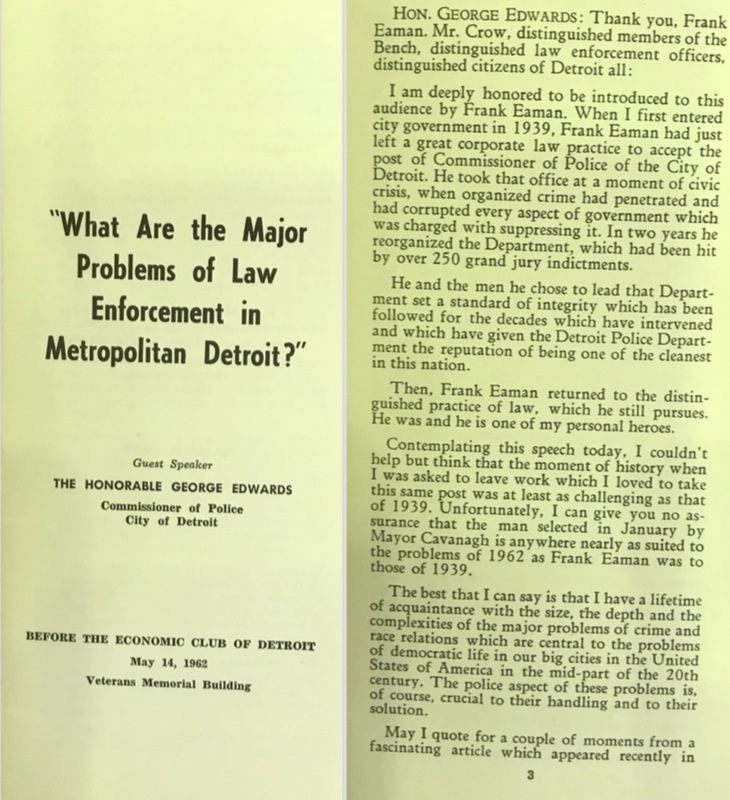

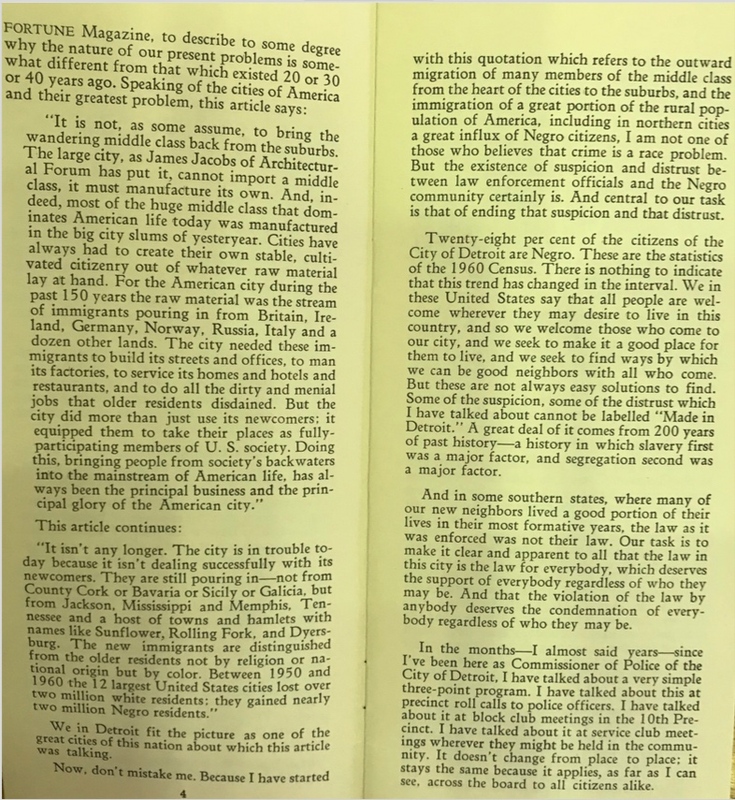

In May 1962, Police Commissioner George Edwards laid out his reform vision in a speech on the "Major Problems of Law Enforcement in Metropolitan Detroit" to a group of white business leaders. He rejected the view that "crime is a race problem," because of the migration of black southerners to the urban North. Instead, Edwards argued that the main problem was "the existence of suspicion and distrust between law enforcement officials and the Negro community." He advocated more effective policing, including far more arrests, in order to protect everyone in the city. This required assuring the black population of Detroit that law enforcement would be fair and color-blind.

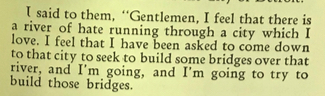

Edwards told the businessmen that he took the job to build a bridge over the "river of hate" that separated white and black Detroit and separated the black community from its police department. He also emphatically challenged the popular white view that equated criminality with the African American community. According to Edwards, "there is not one single neighborhood in the city of Detroit where the overwhelming majority of residents are not themselves law-abiding citizens." He finished with an eloquent flourish, that the law-abiding black people in Detroit would never know true liberty unless they could trust rather than fear their police department.

Read Edward's full speech in the gallery below.

Commissioner Edwards worked to build the trust of the black community through promises of fair law enforcement. He proposed greater police professionalism through higher wages and promoted human relations training of officers so that they would understand constitutional rights and be more sensitive to people of different races and backgrounds. Most of all, Edwards constantly promised that the DPD would enforce the law equally. For this, the new commissioner received much praise from white liberals and black leaders, including the NAACP, and very positive coverage in the Michigan Chronicle.

Edwards also pledged to hire more African American police officers and admitted that the police department in the past had discriminated against qualified applicants. He guaranteed nondiscrimination in hiring from then on and even promised to publicly discuss any case where the DPD rejected a qualified person because of race. Despite this commitment, very little actually happened in this area, and the percentage of black officers was the same when Edwards stepped down as it had been in 1958, largely because of internal DPD resistance to implementation of this policy.

Edwards also sought to strengthen the toothless Community Relations Bureau (CRB), which the previous Miriani administration had formed as a public relations gesture after the sustained civil rights attack on the crash program. Edwards gave the internal CRB more power to investigate allegations of officer brutality and misconduct, but the proceedings were confidential and all it could do was send its findings to the commissioner. Any disciplinary decisions would still be made by a three-person DPD Trial Board on which the police commissioner had only one of the votes. This remained an ineffective system for achieving punishment when officers brutalized civilians (see below). Edwards, and Mayor Cavanagh, continued to oppose an independent civilian review board, choosing to believe that a reformed DPD could police itself.

Most of all, Edwards believed that fair and equal policing would encourage African American neighborhoods to join forces with the police department to fight crime by reporting it. He understood that in the past, many black residents of Detroit did not trust the police department enough to call on officers, even when they were crime victims. indeed, as the NAACP told the U.S. Civil Rights Commission not long before, many black residents viewed the DPD as an "anti-Negro" agency committed to enforcing racial segregation rather than protecting citizens or fighting crime.

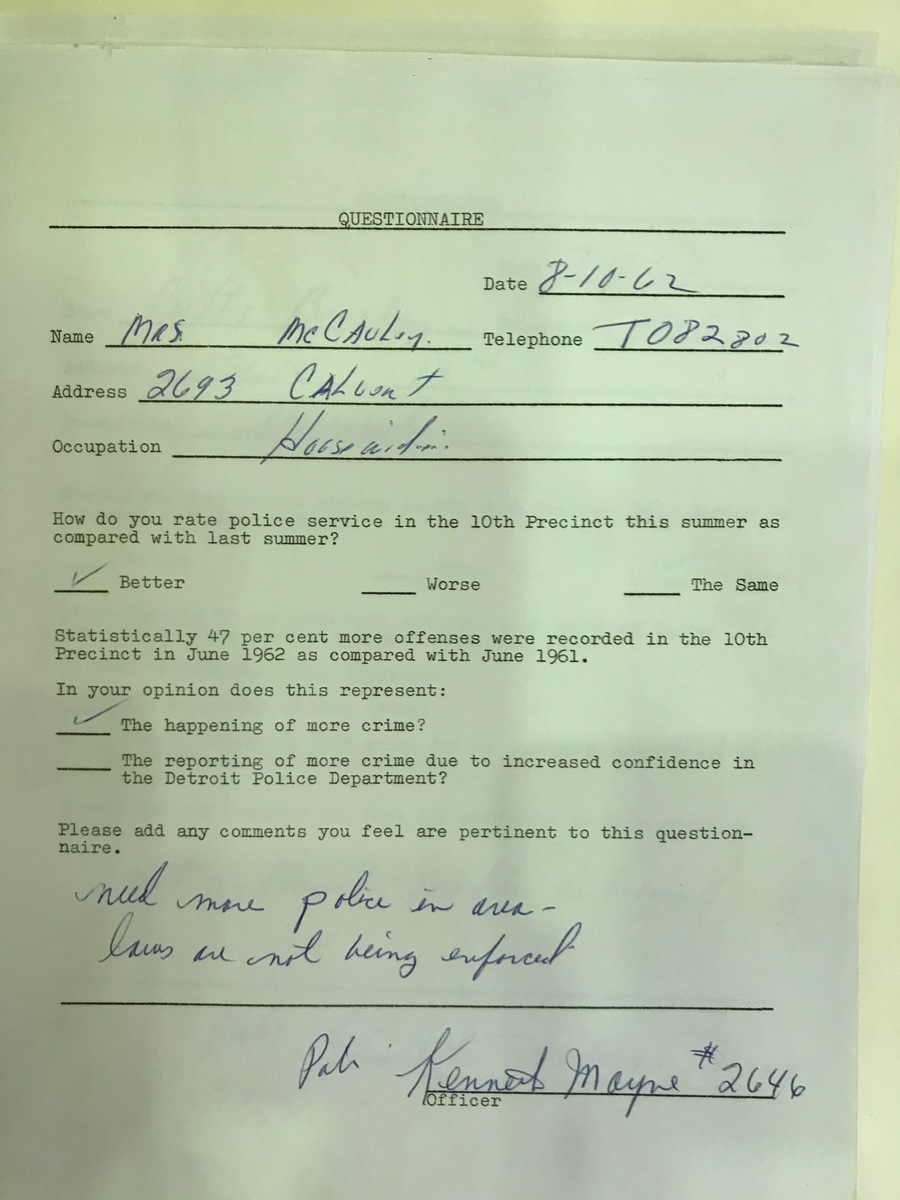

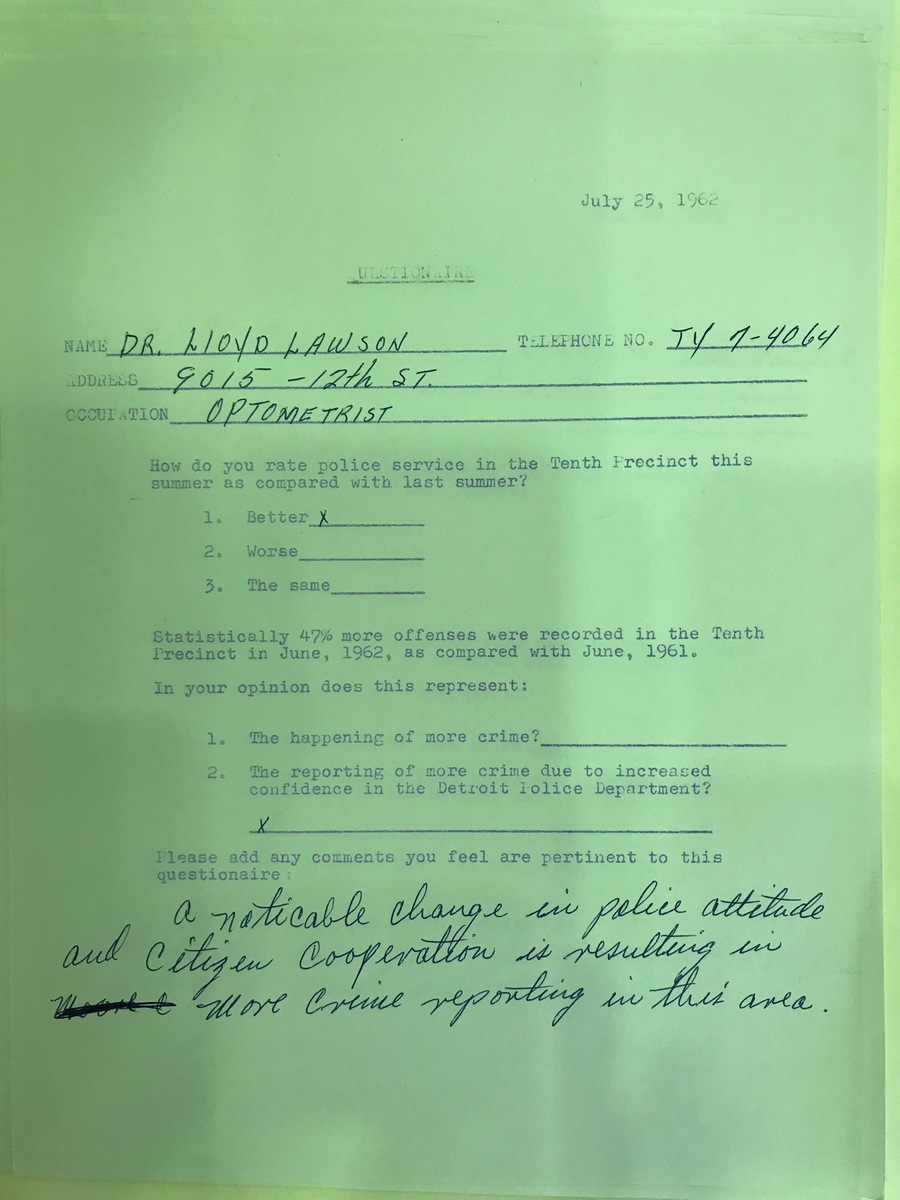

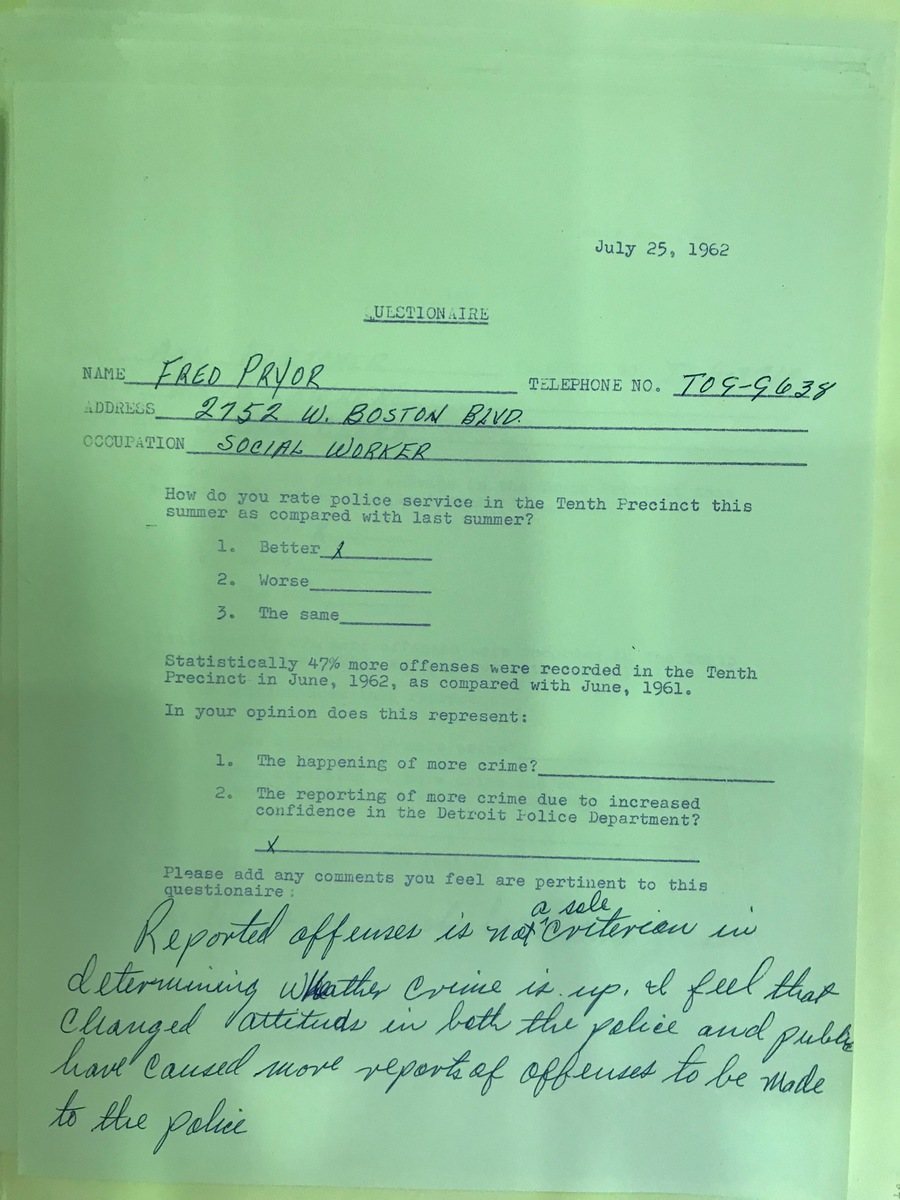

Edwards recognized that the DPD had often not even tried to protect black neighborhoods from crime, a concept known as "underpolicing," which is its own form of racial discrimination. In fact, Edwards interpreted the 12.4% increase in reported crime in Detroit during 1962 as a positive development, because he believed that it meant that "Negroes are getting over their traditional fear of calling upon the police in times of difficulty.". He sent police officials to talk to community groups and neighborhood block clubs, and often did so himself. The DPD also surveyed African American neighborhoods and discovered that many homeowners wanted a greater police presence and believed that the Edwards reforms had improved police-community relations (see gallery below).

Resistance to the Edwards Reform Agenda

Commissioner Edwards's liberal reform agenda and outspoken belief in racial equality produced a substantial backlash from within the police department and from regular white residents of Detroit. Many white Detroiters, and also many police officers, clearly disagreed with Edwards's view that crime was not a "race problem" and that most African Americans in the city were "law-abiding" citizens. They openly talked about "Negro crime" and believed that the police had to use rough tactics in black and integrated/racially transitional neighborhoods. This is yet more evidence of the links between racial segregation and crime politics in the Jim Crow North, given that a majority of white residents openly defended housing segregation and voted for a referendum guaranteeing their right to discriminate in property sales and rentals in 1964.

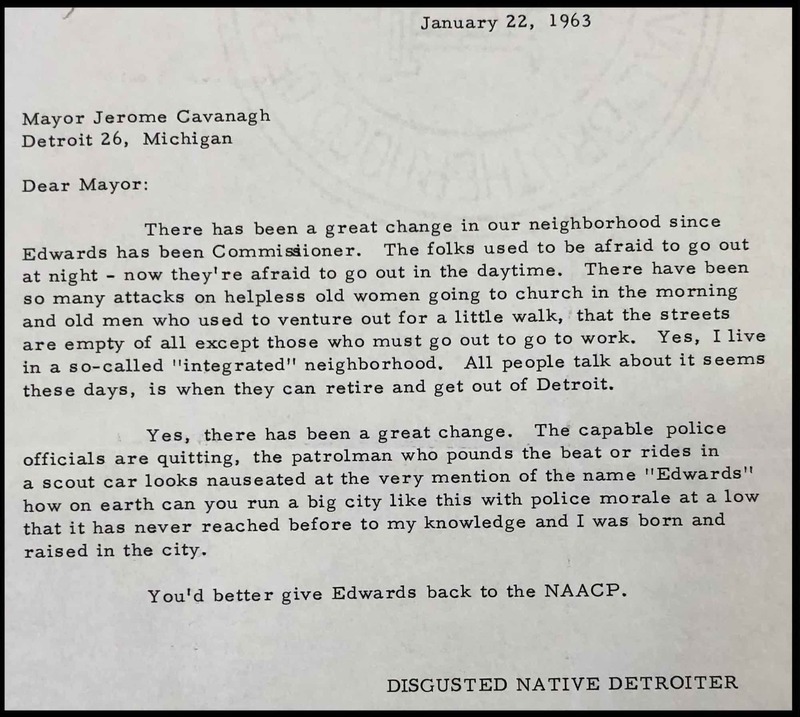

Critics argued that Edwards was "handcuffing the police" and predicted that crime would spiral out of control because of his policies. In the Detroit Free Press, white residents repeated rumors that "officers are afraid of making an arrest in certain areas of the city" and blamed Edwards's softness toward black criminals for an increase in crime (note that Edwards credited black residents for reporting crime). In the letter at right, a "Disgusted Native Detroiter" informed Mayor Cavanagh that [white] people in this person's integrated neighborhood were afraid to leave their homes and that "you'd better give Edwards back to the NAACP."

The fiercest resistance to the Edwards program of racial equality came from inside the DPD. The new commissioner had expected this and jokingly remarked, when taking over, that his chance for success was around 30%. He soon discovered that his enemies in the DPD were manipulating crime statistics in an effort to make it look like his reforms were responsible for an immediate spike in crime. They also planted false and misleading stories about him in the Detroit newspapers. In February 1963, the Free Press even called for a new police commissioner and blamed Edwards for an increase in crime, citing "the feeling among police officers that their boss was less interested in civil safety than civil rights." The Free Press also joined many police officers in rejecting Edwards's efforts to curb illegal investigative arrests and so-called rough justice: "Like the commissioner, we hold no brief for arrests without probable cause, or for unequal enforcement of the law. But neither do we believe that crime can be prevented if law enforcement is limited to tracking down the culprit after the crime is committed."

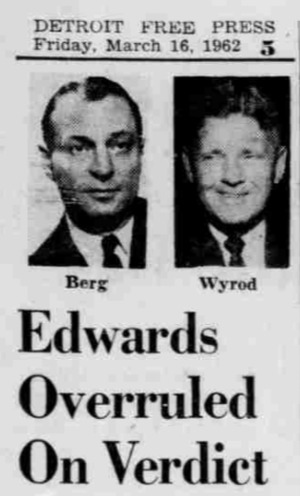

The Berg brothers (above left) led the anti-Edwards campaign inside the DPD. Since 1958, Louis Berg had been the superintendent of the DPD, in charge of tactical operations on the streets. His younger brother, James, was the deputy superintendent. Both men had been centrally involved in the crash program and clearly resented the reform agenda of Mayor Cavanagh and Commissioner Edwards, made possible through the mobilization of African American voters. For the first ten months of 1962, the Bergs worked against Edwards behind the scenes, leaking stories to newspapers, selectively releasing negative information, and encouraging their allies to disparage his agenda. Then, in November 1962, they both quit the force in a dramatic gesture. Despite their resistance to his reforms, Commissioner Edwards was still shocked and dismayed to lose two police officials so valued for their knowledge of crime control tactics. In public, the Bergs and Edwards praised one another after their retirement. In private, DPD sources told the newspapers that the brothers could not stand Edwards's "'accommodation' of Negro groups in Detroit" and rejected his "sociological" approach to crime.

The Edwards-Berg schism revealed two competing models of crime control in the urban North and in 1960s America. The liberal reform model, represented by Edwards and Cavanagh, advocated racial equality in law enforcement in order to make policing more effective by gaining widespread community support, and believed that police brutality damaged community relations and therefore the ability of the police department to work with citizens to fight crime. The Bergs represented a traditional law enforcement model that rejected human relations training as "sociological" and irrelevant, justified the targeted focus on the black community by stating openly that the statistics showed that the "Negro community" committed most of the crime, and opposed "handcuffing" the police through restrictions on the right to stop and search civilians on the street and to use force when they wanted to do so. The Berg model did not ask the question of whether the targeted focus on African American neighborhoods actually created the statistics showing disproportionate "Negro crime," as the NAACP had argued in the recent civil rights commission hearing, that police officers cited and arrested black civilians for all sorts of things that they did not enforce in white areas of the city.

The most damaging resistance to Edwards's reform agenda of racial equality in law enforcement came from police officers who continued to use brutality against African American civilians and an internal DPD investigative process that remained unwilling to punish them. The Willie Daniels case brought the limits of liberal reform into sharp relief.

Willie Daniels and the Limits of Police Reform

On January 28, 1962, a woman named Permetta Jones called police and said that Willie Daniels, an African American man, threatened her with a gun because she owed him $20. They got in a fight, and she hit him over the head with a lamp. When five police officers arrived at Willie Daniels’s home, his wife said her husband was not there, but the police insisted on searching the house and found him hiding in the basement. The police arrested Daniels and searched the house for a gun, but found nothing. Following the arrest, the five officers knocked Daniels on the floor and kicked him. They took him to the precinct station, where he stayed the night and was released the next day, after Jones dropped charges. A doctor examined Daniels the day after the incident and said he had bruises on his legs and that his wrists and stomach were also swollen. Willie Daniels then hired an attorney to file a civil lawsuit against the city of Detroit, the police department, and the five patrolman who beat him.

Commissioner George Edwards had been in charge for less than a month and had promised that police brutality would not be tolerated. Edwards publicly pledged to conduct a prompt and thorough investigation and asked deputy commissioner James Berg to lead it. In March, the case came before the trial board, consisting of three white men: Edwards himself, Superintendent Louis Berg (brother of James), and Chief of Detectives Walter Wyrod. Daniels testified before the trial board and told a convincing story of police brutality. The officers also testified and seemed to have forgotten all of the details after the arrest. To Commissioner Edwards, it seemed obvious that the officers were lying and that they had beaten a prisoner in their custody to try to force a confession. He viewed their actions as criminal and expected the trial board to find them guilty.

Louis Berg and Walter Wyrod disagreed and argued that Willie Daniels had sought to evade arrest by hiding in the basement (although the beating took place after the arrest). They also contended that whenever a civilian's testimony came into conflict with a police officer's, the police officer should receive the benefit of the doubt. This standard, of course, meant that a trial board would almost never, if ever, find a police officer guilty as long as he denied the charges. As they argued, Wyrod said to Edwards: "Boss, we can’t do that. Why, if I voted these men guilty, my own men would never work for me again." The trial board voted 2-1 to exonerate the officers, with Edwards in dissent.

When Edwards announced the decision, he publicly stated that he believed the officers were guilty: "I find, after weighing all the testimony, a deep conviction that Willie Daniels, after being handcuffed, was struck and that each officer struck him at least once."

The exoneration of obviously guilty officers, who had committed felonious assault on an unarmed prisoner in their custody, showed the power of the code of silence among law enforcement and the inability of the police department to police itself. Civil rights and civil liberties groups were very unhappy with the verdict and reiterated their demands for a civilian review board (right), which Edwards continued to oppose. But the episode also made them even more supportive of the commissioner, whom they viewed as an ally in the fight for racial equality and police reform.

Black radicals in Detroit were less forgiving of Edwards and accused him of not taking strong enough steps to curb police brutality. A group called the Independent Negro Committee to End Racism and Ban the Bomb wrote the commissioner after the trial board exoneration and said the issue was not whether or not Willie Daniels had committed a crime, but "whether any policeman has a right to beat any Negro, whether guilty or innocent."

Brutality remained an endemic problem in police interactions with African Americans, despite Edwards's efforts to reform the DPD. Even a civilian review board would not have solved the problem, because police violence and misconduct were part of the way that discretionary policing operated in aggressive crime control, which Edwards strongly supported. And his toughest challenge lay on the horizon, when a massive protest movement by mainstream and radical civil rights groups erupted after Edwards participated in the exoneration of a white officer who killed a black woman in July 1963.

Edwards's Final Months as Commissioner

In July 1963, Commissioner George Edwards and the DPD received widespread praise for the peaceful civil rights march of 125,000 people in downtown Detroit, followed by large protests and unanimous condemnation from African American groups after he personally exonerated a white officer who shot and killed a black woman, Cynthia Scott. Edwards resigned from the DPD soon thereafter, with a decidedly mixed legacy. He took on the job of police commisioner with strong support from Detroit's African American leadership, but in the end his policies were not capable of reforming the DPD and changing the patterns of racially discriminatory and brutal policing in the city's black neighborhoods.

Throughout Edwards's time as police commissioner, there were rumors that President John F. Kennedy was eyeing him for an appointment to the federal appeals court for the Sixth Circuit. The anger of African American groups after the Cynthia Scott exoneration briefly threatened his appointment, but Lyndon Johnson ultimately nominated him, following the assassination of President Kennedy. Edwards resigned as police commissioner on December 19, 1963, and spent the rest of his distinguished career as a federal judge. He tried diligently to bridge the "river of hate," but he left behind a city in turmoil.

Sources:

Charles William Ungermann Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

Detroit Free Press, March 16, 1962

Detroit News, January 15, 1963

George C. Edwards, Jr. Papers, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Jerome P. Cavanagh Collection, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

American Civil Liberties Union of Michigan/Metropolitan Detroit Branch Collection, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Detroit Commissions on Community Relations (DCCR)/Human Rights Department, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Image Gallery, Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University

Charles William Ungermann Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

Mary M. Stolberg, Bridging the River of Hatred: The Pioneering Efforts of Detroit Police Commissioner George Edwards (1998)

Heather Ann Thompson, Whose Detroit? Politics, Labor, and Race in a Modern American City (2017)

ACLU Papers, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

DCCR Papers, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University