3. Corruption in the DPD

The Detroit Police Department as an institution, and many of its individual officers, engaged in a wide range of corrupt and illegal activities. Some of this conduct was pursued in secret and was endemic in law enforcement agencies across the nation, most notably the unconstitutional surveillance and harassment of civil rights organizations and other radical activists on the political left. Other aspects of police corruption were so widespread as to constitute formal--if unstated--DPD policy toward the African American community, including warrantless home invasions, racial profiling and unconstitutional "stop and frisk" searches of motorists and pedestrians, and routine coverups of brutality and misconduct toward civilians.

A third category of police corruption involved individual officers, at times operating through small networks within the department and in their precincts, who engaged in explicit criminal conduct such as taking narcotics payoffs and committing sexual assaults. While the DPD did not condone such criminal activity, the police hierarchy also minimized its scope, did not always try very hard to eradicate it, and often placed obstacles in the way of anti-corruption investigations of its officers.

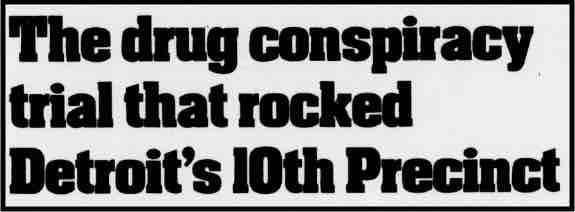

The Pingree Street Conspiracy, first exposed by the Detroit Free Press in the spring of 1973, provided a window into the depths of narcotics corruption in the DPD but also indicated the lengths to which police networks would go to obstruct criminal investigations. The Pingree Street Conspiracy, covered in detail later in this section, resulted in the indictment of ten police officers in the Tenth Precinct for crimes that included supplying street dealers with heroin, robbing and extorting other dealers, leaking information about police raids, and offering major traffickers protection from investigation. Only three of the officers were ultimately found guilty, and investigators estimated that at least two hundred members of the DPD, included high-ranking officials, were actively involved. The Pingree Street investigation ended with a widespread consensus that powerful forces inside the DPD had managed to successfully cover up the depth and extent of law enforcement involvement in not only taking heroin payoffs but actively facilitating and regulating the illegal narcotics market.

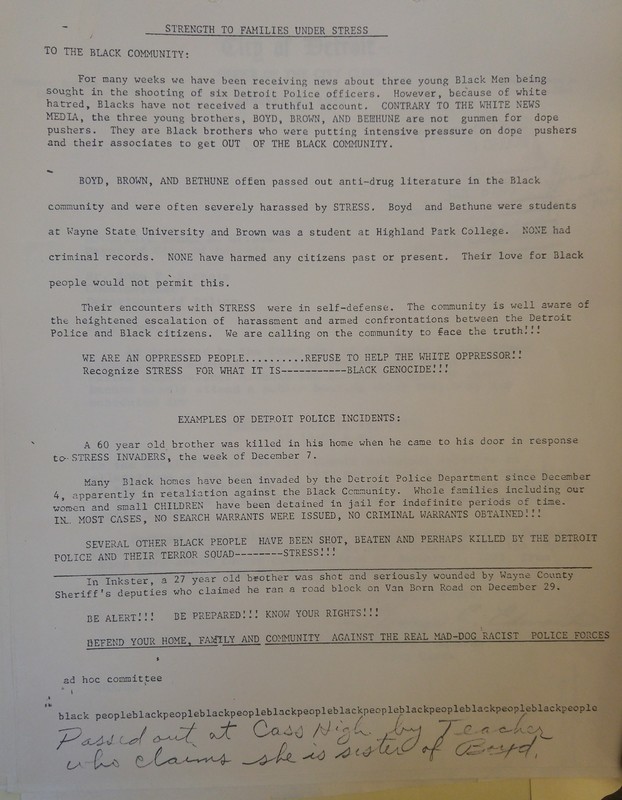

This section includes detailed pages about three controversies that blew the issue of police corruption wide open in 1972-1973: the Rochester Street Massacre, STRESS Patrolman Raymond Peterson's coverup of murder, and the Pingree Street Conspiracy. While only the Pingree Street Conspiracy trial directly implicated DPD officers in narcotics corruption, anti-STRESS activists demanded to know whether the police vs. police ambush in the Rochester Street Massacre also resulted from a law enforcement turf war over control of heroin payoffs, and the eight civilian fatalities that Patrolman Peterson committed or participated in raised additional questions about the motives and patterns of STRESS killings. The DPD's manhunt for three Black anti-narcotics activists during late 1972 and early 1973 (covered in the next section) further fueled the speculation that the extraordinary violence committed by STRESS officers was not random but rather potentially linked to police criminality in regulating the narcotics traffic and eliminating dealers who did not pay bribes. "All black people know about police complicity in drugs, about STRESS officers going into dope houses to get payoffs," Ron Lockett, a co-founder of the Committee to Abolish STRESS, argued in the spring of 1973. While hard evidence of these charges was elusive, Lockett claimed that some STRESS teams even supplied the street dealers with the heroin that they sold: "They bring dope to dope houses--I myself have seen this."

The remainder of this overview page examines organized police corruption and criminal conspiracies in the areas of sexual assault of women, "Blue Curtain" coverups of violence against African American youth and Black police officers, and illegal surveillance of political activists.

Sexual Assault of Women by Plainclothes Police Officers

The policing of "vice" markets involving prostitution and narcotics had long facilitated violence by law enforcement officers against women, including sexual assault as well as other forms of physical brutality. The DPD often covered up incidents of sexual violence by its officers and did not fully confront the issue of violence against women until the mid-to-late 1970s, when forced to do so by feminist activism. In one shocking case from 1969, covered in the previous section, the Wayne County Prosecutor dropped charges against two Detroit police officers who had raped and stabbed a 21-year-old African American sex worker after the DPOA union paid her a $5,000 bribe to stop cooperating in the criminal proceedings. Black women were particularly vulnerable to physical and sexual abuse by police officers who often acted in concert with their partners or squad units. The plainclothes disguises and undercover tactics utilized in vice and narcotics enforcement also enabled some police officers to act with more impunity and commit clearly criminal acts.

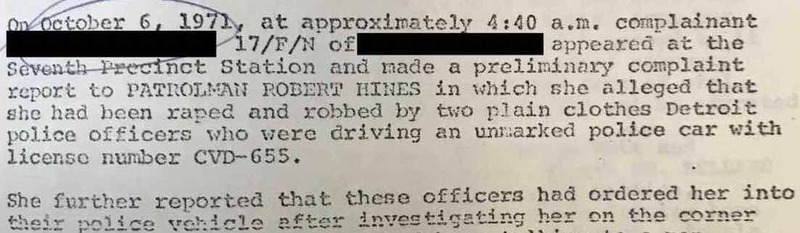

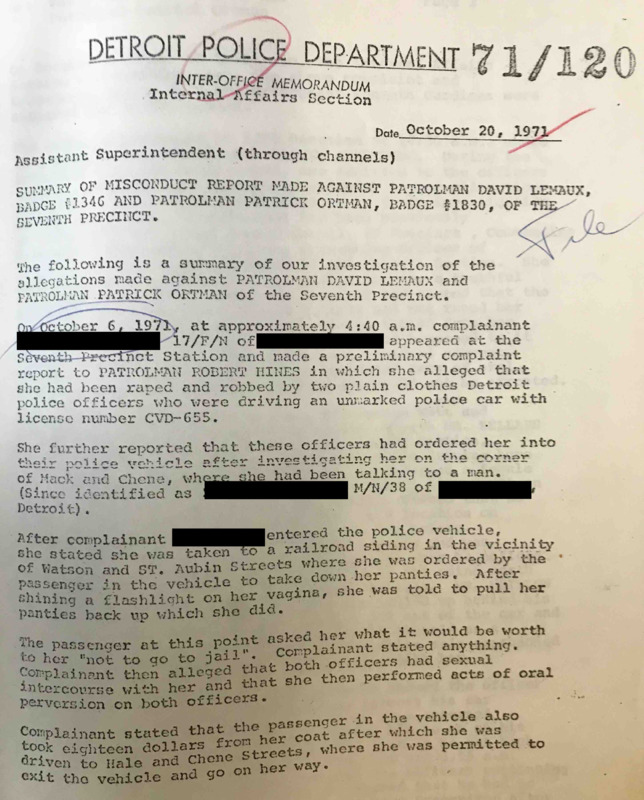

Rape by On-Duty Officers. In October 1971, a 17-year-old African American female filed a complaint that two white Detroit police officers in plainclothes and an unmarked car had raped and robbed her after ordering her into their vehicle in a late-night incident. (Our project has redacted the name of the underage female from the Internal Affairs report excerpted at right and reproduced in full in the gallery below). The partners, Patrolmen David Lemaux and Patrick Ortman, drove the underage female to an isolated location and made it clear that she would be arrested unless she engaged in sexual activities with them. She stated that both men then raped her, took $18 from her coat pocket, and let her go.

The female victim immediately filed this complaint at the 7th Precinct station, around 4:40 a.m. The DPD's Internal Affairs unit launched an investigation and, in the process, the 17-year-old female withdrew her rape and robbery accusations yet insisted that she had oral sex with both officers to avoid arrest. She also admitted to being a narcotics addict but denied that she engaged in prostitution. While it is not completely clear why the female would have withdrawn the rape allegation under police interrogation, the DPD booked her for accosting and soliciting prostitution the day after she filed the complaint, and it seems likely that law enforcement officers sought to coerce the witness. Patrolmen Lemaux and Ortman denied that anything had happened and stated that the female never even got into their car. However, the investigation recovered a pocket knife from the back seat of their vehicle that the female victim admitted she had stashed there to avoid a concealed weapons charge. After this, the officers--with legal assistance from the Detroit Police Officers Association union--changed their sworn statements to admit that they had ordered the "suspected prostitute" into the car after finding her on the street talking to a 38-year-old African American man (name also redacted), and that they had driven her around for a while before dropping her off again, with nothing else happening. Lemaux and Ortman refused to answer additional questions and were suspended under DPD regulations when they further refused to take a lie detector test. Internal Affairs did administer a polygraph test to the female victim who had been charged for prostitution and, after finding that she was "telling the truth," requested a warrant for arrest of the two officers. The Wayne County Prosecutor denied the warrant request, citing lack of evidence for their alleged crime because it was based only on the word of a "suspected prostitute." The administrative suspension was the extent of the officers' punishment for the sexual assault of a 17-year-old female.

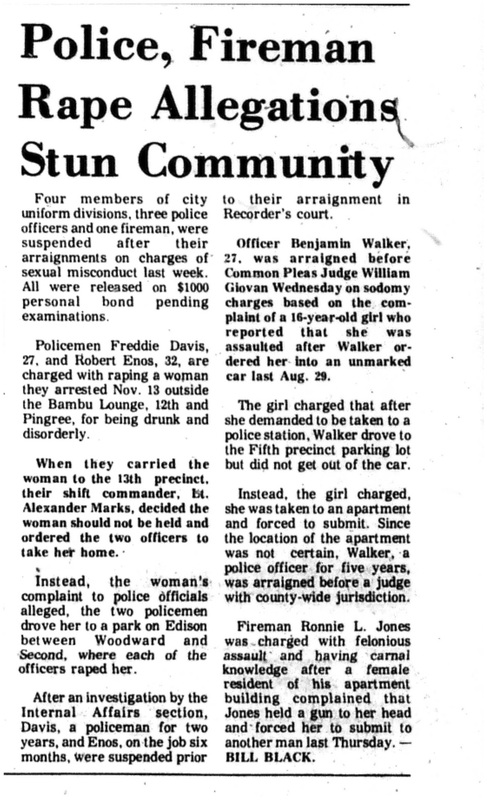

Two years later, the Michigan Chronicle reported on rape and sexual assault allegations against three more DPD officers (gallery below, second from left). Officers Freddie Davis and Robert Enos arrested a woman for being "drunk and disorderly" and then raped her in a secluded park near Woodward Avenue. Both were suspended in advance of their arraignment. Officer Benjamin Walker also faced charges for detaining a 16-year-old female while driving an unmarked car and then sexually assaulting her in a private apartment. These documented cases, which required female victims to go to the precincts of the officers involved in order to file criminal complaints, are likely only the tip of iceberg.

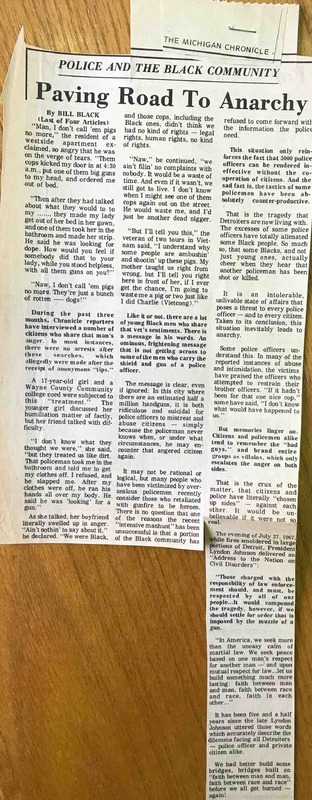

Sexual Assaults and Cover Ups by STRESS. Plainclothes officers in the undercover STRESS unit faced multiple allegations of sexual assault against African American women, usually during warrantless (illegal) searches of cars and private homes. This was part of a broader pattern of male police officers ordering female civilians to strip off their clothes during crime investigations, especially involving narcotics "suspects," and then physically groping them or worse. Although this type of misconduct and brutality presumably happened across multiple police units, it was particularly common in plainclothes and undercover operations where victims could not identify the officers by name and badge number.

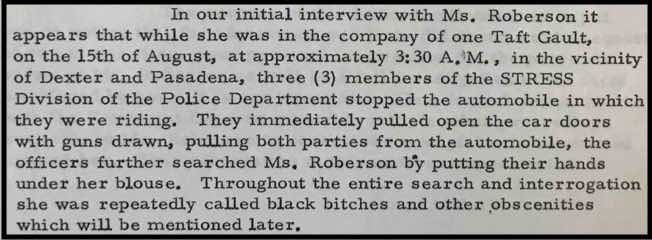

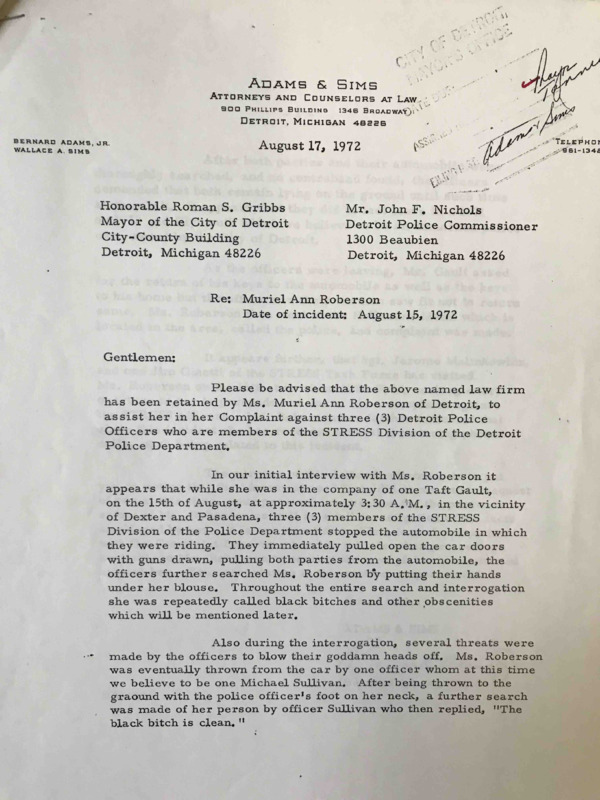

In 1972, Muriel Ann Roberson filed a civil lawsuit against the Detroit Police Department alleging sexual assault and other misconduct by three plainclothes STRESS officers in an unmarked car who pulled her and a male companion over at 3:30 a.m. Roberson could not identify the undercover officers, an endemic issue in plainclothes operations that facilitated police criminality and made it extremely difficult for victims to file brutality and misconduct complaints. She alleged that the STRESS team held the couple at gunpoint for no legitimate reason, roughly groped her chest area during an alleged search, threw her onto the ground, called her a "black bitch," and made multiple threats to "blow their goddamn heads off" (gallery below, second from right). Then, after she filed a complaint to the DPD, two STRESS officers visited her home at 11:00 p.m. to pressure her into withdrawing the allegations, and she received multiple anonymous threatening phone calls as well. After STRESS officers sought to silence and intimidate the victim, the DPD did not pursue the complaint and the civil lawsuit did not succeed, in large part because of the deniability afforded to undercover units by their lack of identification.

STRESS teams also committed sexual assault and other forms of violence and misconduct toward women during the monthlong manhunt that resulted in widespread abuses of African American residents of Detroit during December 1972 and January 1973. In an investigation, the Michigan Chronicle documented numerous incidents that took place during illegal home invasions where STRESS officers without warrants terrorized innocent citizens. In one incident, a group of officers kicked in an African American couple's door at 4:30 a.m., held them at gunpoint while they were still in bed, and forced the female to strip out of her nightgown--claiming to be looking for drugs. In another, armed officers broke into an apartment where Black college students were having a party, forced the males against the wall and then made the females under the pretense of checking to see if they were hiding any weapons. In a third case, police officers ordered a 17-year-old female to remove her clothes, claiming to be looking for a gun. When she refused, the male officer slapped her, forced her to disrobe, and "ran his hands all over my body." Her enraged boyfriend, who was present, told the Chronicle that it would be too dangerous to file a complaint because STRESS officers would likely retaliate against them, maybe even murder them.

Read the full accounts of these incidents in the gallery below.

"Fifth Precinct Incident" and the Blue Curtain

The "Fifth Precinct Incident" saga during 1972-1973 became famous for illustrating the power of the so-called Blue Curtain, the street-level code of silence that shielded police officers who committed criminal acts of brutality as well as the corrupt and organized conspiracy by the Detroit Police Department as an institution to cover up such criminal misconduct. While police brutality against African American civilians was a rampant problem in the DPD, the main issue was not individual "bad apples" so much as the broader, systemic culture of covering up their crimes and retaliating against the few officers who dared to buck the Blue Curtain.

On July 22, 1972, a DPD scout car responded to a call and encountered a group of seven African American teenagers in a neighborhood. One of them had discovered an American flag in a trash can, and there are conflicting accounts of what happened when the police arrived. Curtis Lewis, a 14-year-old, stated that he and some friends, were playing keepaway with the flag when a group of white officers approached and grabbed the flag while using racial epithets and claiming it was being desecrated. Gilbert Lewis, Curtis's father, along with his uncle James Lewis intervened to defend the youth. Gilbert later testified that he "saw them being viciously beaten" and that when he protested, Patrolman Martin Joseph cocked a gun to his head and said, "Stand still, n-----." The police then beat Gilbert Lewis in front of his wife and children, as he begged them to spare his family, and arrested him along with Curtis and James.

The officers claimed that instead, the African American youth were desecrating the flag and responded to the presence of the police by hurling obscenities and then physical assault. In this improbable scenario, a Black teenager kicked a white officer in the shins and then a group of 5-7 African American adults began to attack the armed patrolmen with sticks. The squad car called for backup and transported Curtis, Gilbert, and James Lewis to the Fifth Precinct station. (The three were ultimately acquitted of all charges).

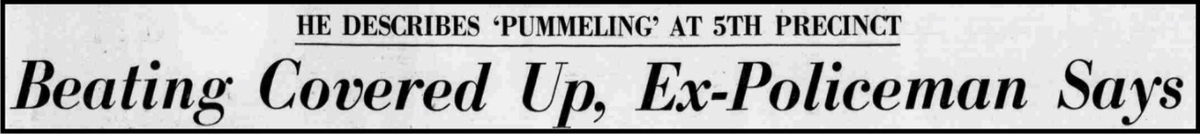

In the precinct parking garage, white police officers viciously beat the three handcuffed and defenseless African American prisoners. Gilbert Lewis suffered a spinal injury and lost consciousness, and his 14-year-old son Curtis received two black eyes and suffered what his lawyers labeled long-term "severe mental anguish." The worst abuse happened to James Lewis, who arrived in a separate squad car during a shift change and was beaten in a racist frenzy, akin to mob action, by between 15-20 white officers. Two African American rookie officers, Glenn Walker and Curtis Burton, intervened to try to stop the assault and were themselves beaten severely by the white law enforcement gang. A single white officer, a 23-year-old rookie named Jeffrey Patzer, witnessed the incident in shock and then reported what happened to his superiors. When they refused to investigate and warned him to be quiet, he told his story to the newspapers and eventually to an internal Trial Board that did not convene until April 1973, when the DPD coverup began to unravel nine months after the "Fifth Street Incident." By then, the DPD had forced Officer Patzer to quit in retaliation for his decision to cross the Blue Curtain. The DPD also initiated Trial Board proceedings against Patrolmen Walker and Burton, the two Black officers who tried to stop the incident and then filed their own reports, in an effort to intimidate them as well.

The white officers claimed that James Lewis managed to get free inside the precinct parking garage and kicked one of them in the groin, requiring them to use force to subdue him. Jeffrey Patzer disputed this cover story and described a "multitude of blue-suited policemen swinging in melee fashion, just pummeling the guy," with a line of officers yelling "'My turn,' 'My turn'" and then joining in. Patzer emphasized that the victim, James Lewis, was handcuffed with his hands behind his back throughout the assault and seemed close to death. One officer, Patrolman Gerald Joseph, began jumping up and down on James Lewis's head. Then Curtis Burton, one of the two Black officers, intervened and pushed Patrolman Joseph off of the prisoner, which caused a large group of white officers to begin beating Patrolman Burton with fists and flashlights. White officers also attacked his partner, Patrolman Glenn Walker, in what the DPD inaccurately labeled a racial brawl. The prisoner, James Lewis, and the two African American officers were hospitalized.

"Boys will be boys." Officer Patzer immediately reported what he had witnessed to two sergeants inside the precinct building. One said that the officers were just letting off steam, and the other responded, "boys will be boys." When Jeffrey Patzer persisted, his superiors warned him that he would either be reassigned to walk a midnight beat alone or be "bumped off." He resigned the next day and told his story to the newspapers instead. Patrolmen Burton and Walker also filed reports charging the white officers with brutality, but the DPD covered this up as well. The Fifth Precinct's internal investigation concluded that the white officers had used "no more force than necessary" to arrest and restrain the Lewis family members and instead recommended disciplinary action against the two Black patrolmen, Burton and Walker, for allegedly drawing their guns on their fellow officers, a fabricated charge.

Nine months later, after a front-page expose in the Detroit Free Press, the DPD came under pressure from the city council as well as the Guardians of Michigan and the Concerned Police Officers for Equal Justice, two civil rights associations for Black officers that were actively protesting racial discrimination in the DPD at the time. A DPD spokesman dismissed Patzer's account, stating that "eyewitnesses aren't always right," and the department also initiated Trial Board proceedings against the two Black officers, Patrolmen Burton and Walker, for "conduct unbecoming an officer" by alleging that they had started the fight by improperly threatening other police officers with firearms. In his report to the city council, Commissioner John Nichols showed that the corrupt coverup conspiracy went all the way to the top, preemptively exonerated all of the white officers, and blamed the Lewis family for their own injuries:

To resolve the public controversy, after nine months of a complete Blue Curtain whitewash, the department reluctantly initiated a Trial Board hearing against a single white officer, Patrolman Gerald Joseph, who had stomped repeatedly on James Lewis's head. Patrolman Joseph claimed to be acting in self-defense but admitted to putting his foot on Lewis's neck to restrain him, and the Trial Board found him guilty of "mistreating a prisoner" and suspended him without pay for 30 days. The Trial Board proceedings did clear the two African American officers of any wrongdoing, but the DPD did not bring any additional internal charges against the more than a dozen other white officers who participated in the assault. Two of the three Trial Board members later said that they believed at least 10 white officers had lied in their testimony, but nothing came of that in the end either.

The token administrative punishment received by Patrolman Joseph was far more than usually happened when DPD officers committed felony assaults against civilians. Without the refusal of a white police officer to go along with the coverup of the "Fifth Precinct incident," the Blue Curtain would have held up completely. But in the end, the DPD still succeeded in suppressing the evidence of the violent criminal conduct and conspiracy to concoct a false cover story by more than a dozen white police officers both at the scene in front of the Lewis's house and in the Fifth Precinct parking garage.

Illegal Surveillance of Political Activists and Organizations

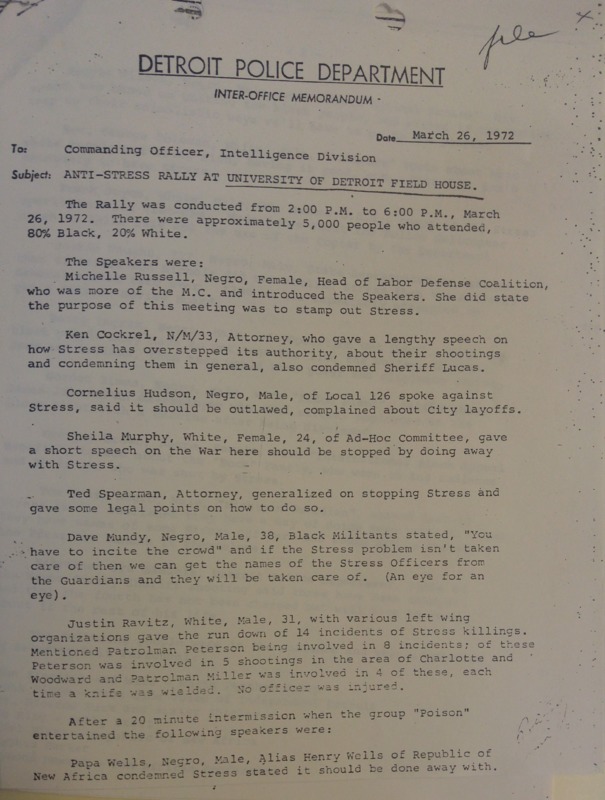

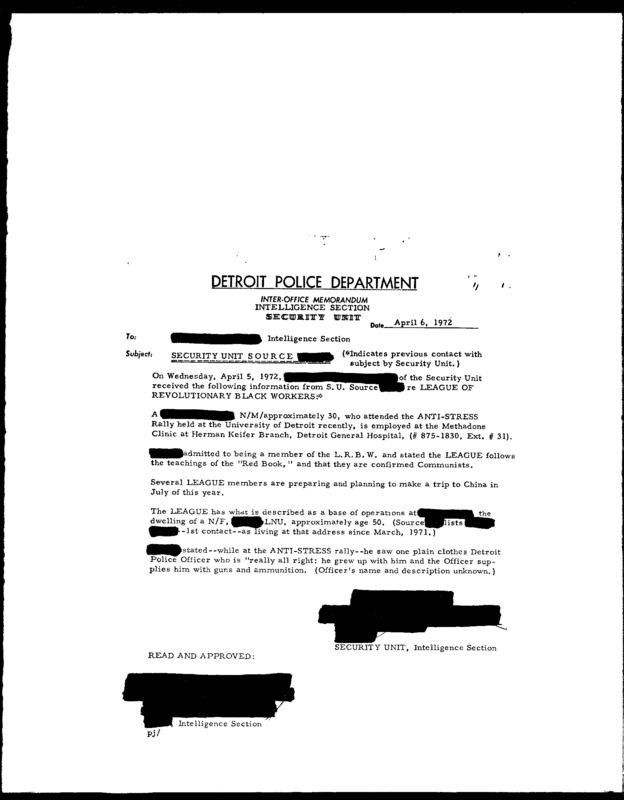

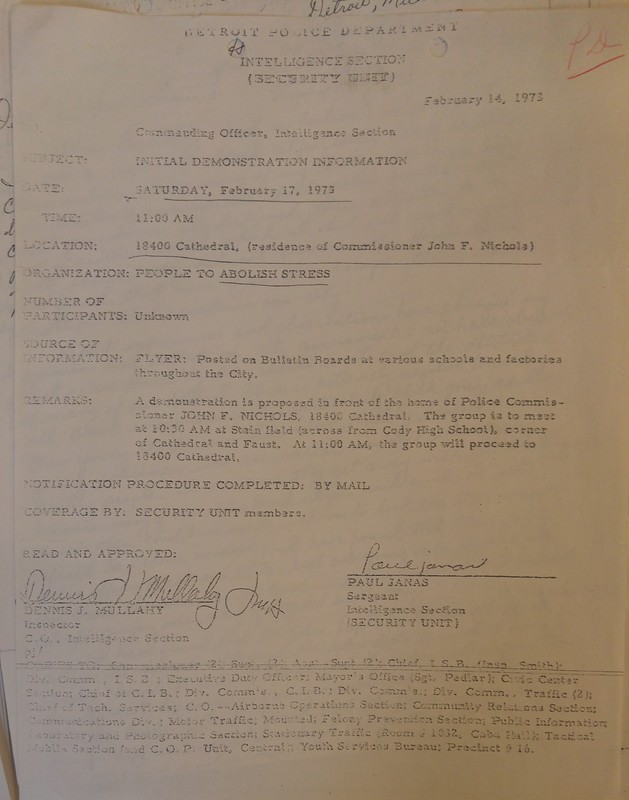

The Detroit Police Department systematically broke the law and violated the U.S. constitution through its program of surveillance against political activists and groups defined as "subversive." This program was a centerpiece of the DPD's repression campaign against Black radical organizations and a clear example of how the police department intervened as a right-wing political institution, not just a crime control agency, in Detroit politics. The secret DPD operation was based in the Criminal Intelligence Bureau and worked in parallel with the clandestine Special Investigation Unit of the Michigan State Police, which also violated civil liberties on a mass scale. Along with similar operations in urban police departments across the nation, the DPD provided and received information from the FBI's COINTELPRO program, whose mission was to "disrupt" and "neutralize" civil rights, black power, New Left, and other progressive and radical organizations and movements. The scope of the DPD's political surveillance activities, covered in detail in previous sections of the exhibit (see the Red Squad and Political Surveillance pages), came to light starting in the mid-1970s, when lawsuits revealed that the police department had compiled secret files on 1.4 million people since the 1940s.

In spring 1971, a coalition of Black activists led by Coleman Young and Kenneth Cockrel demanded the abolition of the DPD's Criminal Intelligence Bureau as an "illegitimate intrusion of the police into the political sphere." The DPD adamantly refused and in fact had long been spying on both men, who would soon become leading figures in the anti-STRESS campaign. Cockrel, who was the driving force behind the State of Emergency Committee's anti-STRESS protests and the attorney for the League of Revolutionary Black Workers and other radical groups, faced almost constant harassment from the Detroit Police Department, including dozens of traffic citations each year in addition to being under frequent surveillance. The Criminal Intelligence Bureau also sent undercover spies into meetings of the anti-STRESS coalition to gather information and seek to disrupt operations, as did the Special Investigation Unit of the Michigan State Police.

The gallery below includes four archival documents that provide only a sampling of the massive illegal political surveillance operation conducted by the DPD against anti-STRESS activists and events during 1972-1973, especially during the protests that escalated after the Rochester Street Massacre and after the abusive manhunt. The map below the gallery documents additional examples of systematic police surveillance and infiltration of the anti-STRESS campaign.

The interactive map below documents 14 separate incidents of illegal surveillance by the DPD or the Michigan State Police (MSP) against the anti-STRESS movement between 1971 and 1973. The groups surveilled include the State of Emergency Committee, Ad-Hoc Action Group, Socialist Workers Party, Labor Defense Coalition, From the Ground Up, and Families Under STRESS. This is likely only a fraction of the anti-STRESS surveillance conducted by the DPD and MSP, and definitely only a small percentage of the illegal police spying on radical political organizations in Detroit during this time period. The secret police documents that this map is based on come from the archival papers of Kenneth Cockrel and Sheila Murphy at Wayne State University's Reuther Library and represent only the meetings and protests that one or both of these anti-STRESS leaders attended. Under a series of controversial state laws and litigation settlements in the late 1970s and 1980s, after the exposure of mass police surveillance, only the individual person surveilled can request access to the secret files. Based on archival restrictions, the documents that this map is based on cannot be directly quoted from or reproduced.

Kenneth Cockrel, a key leader of the State of Emergence Committee, also co-filed the Labor Defense Coalition's civil lawsuit against STRESS in April 1972. Sheila Murphy, who later married Kenneth Cockrel, founded the Ad-Hoc Action Group, an anti-police brutality organization, in 1968 and also played a central role in the anti-STRESS campaign, including through the white radical organization From the Ground Up. The Cockrel and Murphy archive also includes 18 other incidents of police surveillance of one or both of these activists between 1965 and 1970, not included on this STRESS map (visit this page for a map showing all of these surveillance incidents between 1965 and 1973).

Click on the dots to read the incident descriptions of each STRESS event placed under surveillance, and zoom the map to view the high concentration of surveilled organizational meetings (often in progressive churches) and protests in downtown Detroit. In particular, it is necessary to zoom to view the cluster of four protest incidents that took place outside of the DPD's downtown headquarters at the intersection of Beaubien and Monroe.

Map of 14 Incidents of DPD and MSP Surveillance of Anti-STRESS Events, 1971-1973

Sources

Howard Kohn, "6 Policemen's Roles Bared in Probe of Heroin Racket," Detroit Free Press, April 29, 1973

Judith Frutig, "Beating Covered Up, Ex-Policeman Says," Detroit Free Press, April 9, 1973

Additional sources for "Fifth Street Incident": Detroit Free Press, April 10, 14, 17, 28, May 2, 10-11, 1973

Detroit Free Press, August 5, 1972, July 31, 1975, Sept, 26, 1976

Detroit News, May 4, 1971

The Fifth Estate, April 1973

Michigan Chronicle, Jan. 20, 1973, March 17, 1973, Dec. 1, 1973

Roman S. Gribbs Mayoral Records, Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library

Detroit Commissions on Community Relations (DCCR)/Human Rights Department, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Kenneth V. and Sheila M. Cockrel Collection, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University