Community Pushes Back

The Rochester Street Massacre of March 9, 1972, created a political crisis for the STRESS operation and inspired a second round of mass protests, six months after the first wave by the State of Emergency Committee in response to the killings of teenagers Ricarco Buck and Craig Mitchell. Unlike most other STRESS homicides, the DPD was not able to completely cover up the circumstances of the Rochester Incident, in which a STRESS team and its DPD backup fired more than 40 shots into a private apartment, fatally shot Sheriff's Deputy Henry Henderson, and wounded several other African American law enforcement officers.

The uproar in the Black community was immediate and escalated even further five days later, when a white STRESS officer shot and killed Curtis McConnell, a 15-year-old African American male, in suspicious circumstances during a decoy operation. Patrolman Gary Boiger, who had already shot five other Black civilians non-fatally, claimed that the teenager lunged at him with a knife. Radical left groups led by the Labor Defense Coalition denounced Patrolman Boiger as a murderer, and mainstream civil rights organizations including the NAACP and Urban League also condemned STRESS's "shoot first" philosophy. The DPD covered up what really happened in the McConnell killing, and as usual the Wayne County prosecutor did as well. Seven years later the city of Detroit settled a lawsuit brought by Curtis McConnell's family and acknowledged that Patrolman Boiger had lied about being attacked, shot the youth in the back as he fled, and "used unjustified deadly force."

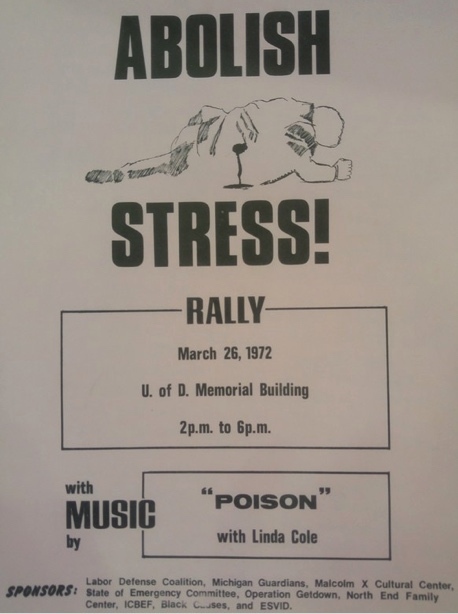

The spring 1972 campaign to abolish STRESS culminated in a mass demonstration on March 26 and a lawsuit filed by the Labor Defense Coalition (covered on the STRESS Trial page) accusing STRESS of being a "murder squad" that must be disbanded. In an effort to salvage the STRESS operation and quell the public fury, Mayor Roman Gribbs forced the DPD to scale back the decoy program and make some other cosmetic changes. Although STRESS officers killed five more people after the McConnell shooting, and engaged in massive abuses during the manhunt of December 1972/January 1973, only one of these fatalities came through the decoy tactic that had resulted in most of the 17 STRESS homicides up through March 1972. This outcome demonstrated the political power of the African American community, mobilized broadly across traditional lines of division, to force changes even under a conservative white-dominated police department and mayoral administration.

Campaign to Abolish STRESS

The shocking news of the Rochester Street Incident brought immediate condemnation from civil rights, black power, and radical left organizations in Detroit. The Guardians of Michigan, an association of African American police officers that had labeled STRESS a "form of genocide" against Black people after the Buck and Mitchell killings, demanded "the elimination of STRESS as of today" and called on all Black officers to quit the unit. The Guardians further denounced STRESS as a "murder squad" and "assassination squad" and threatened to initiate a recall campaign of Mayor Gribbs unless he ordered Commissioner Nichols to disband the unit (gallery below, left).

The Detroit chapter of the NAACP, whose leadership had somewhat tentatively endorsed the State of Emergency Committee protests in September 1971, passed a much stronger resolution calling on Mayor Gribbs and Commissioner Nichols to abolish "the entire STRESS operation." The civil rights organization blamed STRESS for rupturing the relationship between the police department and the Black community through its "shoot first, ask questions later" mentality (gallery below, second from left).

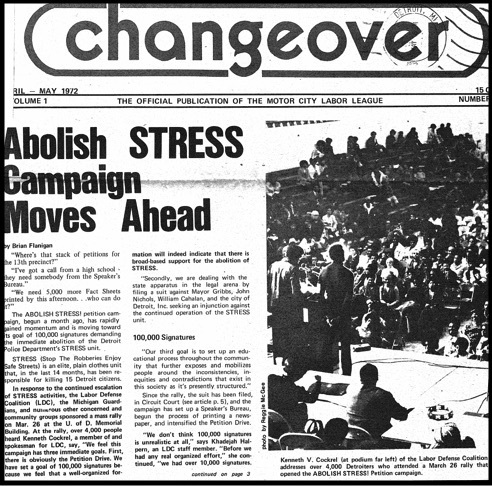

The radical Labor Defense Coalition continued to spearhead the campaign to abolish STRESS through its unity coalition, the State of Emergency Committee. On March 26, the LDC organized a mass "Abolish STRESS!" rally at the University of Detroit, drawing a crowd of around 5,000 people, approximately 80% African American and 20% white attendees. The rally marked the launch of a petition drive against STRESS demanding that Mayor Gribbs and Commissioner Nichols abolish the unit (gallery below, second from right). Ken Cockrel, the cofounder of the LDC, gave the main address accusing STRESS of a pattern of murder and charging the DPD and the Wayne County Prosecutor with systematic coverups. More than a dozen other speakers denounced STRESS as a racist terror campaign, with many comparing its operations to the U.S. "search and destroy" tactics in the Vietnam War, and called dramatic reforms to disarm the police and bring the DPD under civilian oversight.

The Intelligence Division of the Detroit Police Department conducted a surveillance operation of the anti-STRESS rally, part of its broader illegal spying campaign against the anti-STRESS movement and other radical activists in Detroit. The DPD surveillance report (gallery below right) listed 48 members of the audience by name, meaning that the Intelligence Division had active files on each of them, as well as a rundown of the remarks made by each of the speakers.

Preserving STRESS through Modest Reforms

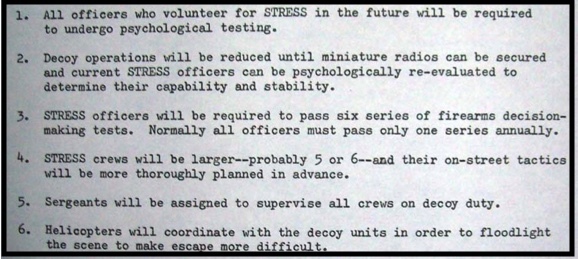

On March 17, Mayor Roman Gribbs addressed the widespread and growing sentiment against STRESS in the city's African American community after the fatal shootings of two more Black males, Deputy Harry Henderson in the Rochester Incident and teenager Curtis McConnell in a decoy operation. The mayor lamented the deaths but insisted that "certain actions which can lead to violence," meaning the aggressive and preemptive tactics of the STRESS unit, were necessary and justified "in the interest of public safety" (gallery below left). He then praised Police Commissioner John Nichols and promised to "make the streets of Detroit as safe as possible for our people, and yet avoid any unnecessary violence." To do so, the mayor announced that he he had directed the DPD to "revamp" the STRESS unit through psychological testing of the officers who volunteered, assignment of command officers to each team, and other reforms to make the program "more effective and more responsible."

The STRESS reforms implemented by Commissioner Nichols were quite limited and in some cases just for show (right). It is notable that the reforms did not include the policies most likely to curb police violence: restraints on the DPD's permissive use of force guidelines, including authorization to shoot unarmed 'fleeing felons'; banning of the entrapment techniques of the undercover decoy operation; barring 'volunteer' officers with a track record of brutality and misconduct complaints by citizens; and a commitment to independent external investigations of police-involved homicides.

- Psychological Screening. The most ineffective reform involved the implementation of psychological screening of officers who volunteered for STRESS, a longtime demand of mainstream civil rights organizations who hoped that this process would weed out racist and violent policemen. Several months later, the DPD announced that all current STRESS officers had passed the psychological assessment--including notorious patrolmen such as Raymond Peterson, who had already participated in the killing of eight African American males and would stand trial a year later for murder.

- Technological Fixes. The "revamp" of STRESS revolved heavily around technological solutions such as better radio communications and the use of helicopters to illuminate crime scenes.

- Better Oversight and Training. The revisions promised better oversight of field operations by commanding officers and more firearms training for patrolmen.

- "Improved" Decoy Operations. Nichols and Gribbs did not end the most controversial and deadly STRESS program, as the activist coalition demanded, but the DPD did end up unofficially pausing the decoy operation pending implementation of these reforms. In November 1972, the DPD announced the resumption of the decoy operations, perhaps suprising observers given that the police department never publicly acknowledged that the secretive undercover operation had been on a temporary hiatus. This news accompanied the first fatal shooting by a STRESS officer since Curtis McConnell in March and also turned out to be the last known decoy operation killing, because the DPD again scaled back the undercover operation after a third wave of mass protests in early 1973.

The Detroit Commission on Community Relations noted that some of the DPD reforms represented a move in the direction of the recommendations made by its own investigation and by the Michigan Civil Rights Commission after the first round of anti-STRESS protests in fall 1972, but the critical problem remained: "They do not attempt to limit the broad discretionary latitude which an officer is allowed in the use of his firearms" (gallery below, second from right).

Conditional Black Support for STRESS Reforms. The Detroit Urban League endorsed the STRESS reforms promised by Mayor Gribbs and Commissioner Nichols, becoming the only prominent civil rights organization not to join the calls for the immediate abolition of STRESS (gallery, second from right). The Urban League, which had long worked closely with the police department and reliably supported tough-on-crime programs, did so with a stark warning, however: either transform STRESS into a "good community protection police unit" or end the program altogether. Francis Kornegay, the executive director of the DUL, criticized the mayor for not imposing any specific use-of-force constraints on STRESS officers and stated that additional killings of unarmed and fleeing youth could not be tolerated. "Muggers should be arrested for the crimes they commit," Kornegay explained, "but they should not be killed for them."

Organized White Support for STRESS. Since the first round of community pushback in September 1971, the Detroit Police Department had consistently argued that a large majority of Detroit residents supported STRESS, including a so-called 'silent majority' of the African American community. While there is no question that Black support for STRESS declined as the unit's body count rose, the white public continued to register strong backing for the crackdown aimed primarily at young African American males on the street. In April 1972, as the anti-STRESS campaign expanded, the DPD announced that private citizens (who lived in white neighborhoods of the city) had collected 10,507 petition signatures and 2,700 postcards expressing their full backing for STRESS (gallery below right). Commissioner Nichols would continue to insist that the overwhelming majority of Detroiters wanted STRESS to protect them from crime until the very last days of the operation, when he lost the 1973 mayoral election on a pro-STRESS platform that drew the votes of most white residents and almost no African American citizens.

Turning the Anti-STRESS Campaign into a Movement

The Labor Defense Coalition and its allies in the anti-STRESS campaign rejected the DPD reforms announced after the Rochester Incident as mere window dressing to preserve a racist terror squad. In the spring of 1972, the LDC and allied groups attacked STRESS on multiple fronts, from street-level organizing to courtroom litigation, part of a conscious strategy to mobilize Black and poor residents of Detroit behind a radical left-labor political movement. According to Sheila Murphy, a white radical activist with the Labor Defense Coalition, "we see this as more than just a movement to abolish STRESS. We think that it is necessary for us to organize in our communities to gain the power that has been taken away from us by Gribbs, Nichols, and the people they work for" (the latter referring to the downtown business establishment).

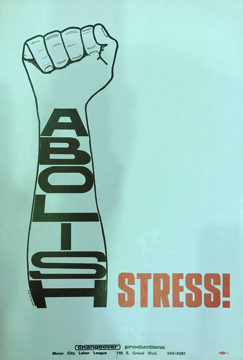

The centerpiece of this movement was the "Abolish STRESS" petition drive launched at the mass rally on March 26 and carried forth by hundreds of LDC volunteers in an organized precinct-level operation. The petition argued that the DPD and the Wayne County Prosecutor had engaged in a corrupt conspiracy to enable police officers to murder Black citizens at will by making clear that every incident would be declared a "justifiable homicide," most recently in the killings of Deputy Henry Henderson in the Rochester Incident and teenager Curtis McConnell on the street. The petition also denounced Mayor Gribbs and Commissioner Nichols for pretending to reform STRESS but really planning to deploy technology in a "conscious escalation of the approach of stopping crime by the method of open terror."

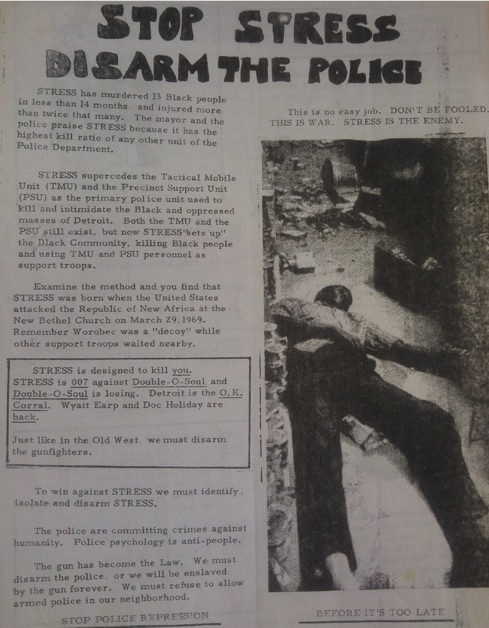

Radical anti-STRESS activists directly compared the DPD's racist war on Detroit's Black neighborhoods to the racist and imperialist U.S. war in Vietnam. According to one flyer circulated in spring 1972, "STRESS patrols see Blacks as the enemy and conduct search and destroy missions in the Black Community to prove it" (gallery below, second from left). Changeover, the publication of the Motor City Labor League, dedicated an entire issue to the analysis of the relationship between STRESS and Vietnam: "Two Fronts-One War" (gallery below left). In an ideological manifesto, LDC leader Ken Cockrel argued that STRESS was a deliberate strategy by "ruling class racists" to distract the public from the crimes and violence of capitalism by turning low-level street muggers into public enemy number one. Cockrel labeled STRESS part of a violent gentrification strategy--"murder by the State as a public relations tactic"--championed by corporate interests to convince white suburbanites that it was safe to shop downtown. The only way for the anti-STRESS campaign to defeat this enemy would be a broad-based political uprising to build a new "system of power for powerless people."

The Labor Defense Coalition and its allied coalition also filed an ambitious and unconventional lawsuit seeking to dismantle STRESS on April 6, 1972. The plaintiffs charged the DPD, Gribbs administration, and Wayne County Prosecutor with engaging in a corrupt conspiracy to deploy deadly force against Black citizens and cover up the actions of a police murder squad. The STRESS trial, covered in the next section, took place in May 1972 and exposed dramatic evidence of DPD criminality and corruption before an appeals court abruptly shut down the proceedings and insulated the STRESS operation and its architects from legal accountability.

The gallery below contains newsletters and flyers by radical anti-STRESS organizations in spring 1972 and the "Why STRESS Must Be Abolished" manifesto by Labor Defense Coalition leader Ken Cockrel.

Sources:

Kenneth V. and Sheila M. Cockrel Collection, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Roman S. Gribbs Mayoral Collection, Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library

Detroit Commission on Community Relations/Human Rights Department Records, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

William Lucas Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

Detroit Urban League Records, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

Toni Swanger Papers, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Changeover (April-May 1972)

Michigan Chronicle, April 1, 1972

Detroit News, June 5, 1972

Detroit Free Press, March 10, Nov. 19, 1972