IN FOCUS: Raymond Peterson

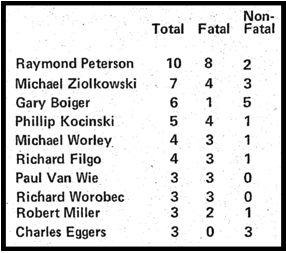

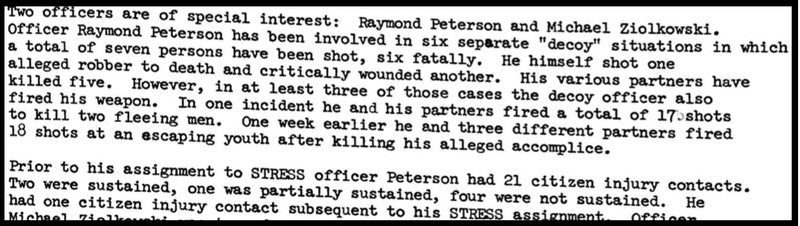

Patrolman Raymond Peterson was the most notorious member of the STRESS unit and probably killed more civilians in separate incidents in a compressed time period than any other police officer in modern American history. During 1971 alone, the first year of the STRESS operation, Peterson's undercover decoy unit was responsible for eight fatal shootings and two additional non-fatal incidents. Raymond Peterson pulled the trigger in at least five of these homicides, all of African American males, all in suspicious circumstances, and fired his weapon in the rest as well. He offered no apologies for keeping the streets safe from "vicious people" and doing his part to maintain order in Detroit's low-income Black neighborhoods, which he considered to be worse than a "jungle."

Before he volunteered for the STRESS unit in 1971, Peterson had compiled a long track record of brutality toward African American citizens since joining the DPD in 1961 as a 25-year-old. This included the vicious beating of Barbara Jackson in 1964, which the DPD covered up until the Michigan Civil Rights Commission found Peterson responsible for violating her civil and constitutional rights in a landmark ruling. Instead of removing Peterson from the force and charging him with felony assault, the Detroit Police Department issued a mild "reprimand" and kept him on the streets. Patrolman Peterson received at least twenty more excessive force complaints from residents of Detroit over the next six years but managed to stay out of the news until September 1971, when the civil rights investigations of STRESS that followed the deaths of Ricardo Buck and Craig Mitchell uncovered the stunning data that a single white officer had participated in seven of the first nine fatal STRESS shootings during a five-month period. In the burst of publicity that followed, Peterson compared himself to a soldier in a war and attributed his frequent use of deadly force to the dangers of walking point in the undercover decoy operation.

In the spring of 1973, Patrolman Raymond Peterson was indicted for second-degree murder for the fatal shooting of Robert Hoyt, a 24-year-old African American male. He admitted to planting a knife on the victim's body but testified that his DPD superiors were really to blame for transforming an ordinary cop into a killer and celebrating his STRESS homicide ratio. A majority-white jury acquitted him despite overwhelming evidence. The circumstances of the Robert Hoyt incident necessarily cast doubt on the cover stories for all of Patrolman Peterson's previous shootings and also raise hard questions about systematic corruption in the DPD Homicide Bureau investigations and internal Trial Board proceedings that repeatedly cleared him, as well as the Wayne County Prosecutor's eight previous determinations of "justifiable homicide."

Any balanced historical assessment of Raymond Peterson's role in the STRESS operation must implicate broader DPD policies and the reflexive justification of deadly force by the Wayne County Prosecutor, not just the actions of an individual officer. The architects of STRESS--in particular Commissioner John Nichols, Commander James Bannon, and Mayor Roman Gribbs--designed the operation to "effectively police the black community" through the omnipresent threat of deadly force and the empowerment of undercover units to exercise preemptive and discretionary violence on the streets. Patrolman Raymond Peterson was the deadliest individual officer in the deadliest police unit anywhere in the United States during the early 1970s, but he also did what he did as an instrument of the Detroit Police Department and the white political leadership of the city.

The Deadliest Police Officer in the Nation

Patrolman Raymond Peterson participated in eight fatal encounters in undercover decoy operations from April-November 1971 and personally shot and killed the African American male 'suspects' in at least five of them, and probably seven. All of these incidents raise questions of excessive and unjustified force, and at least two appear likely to have been premeditated murder, a preview of Peterson's killing of the unarmed Robert Hoyt in March 1973. Based on Peterson's admission that he planted a knife to frame Robert Hoyt, and the habit of many DPD officers to carry "drop" weapons in case they shot someone, the 'discovery' of knives on the alleged suspects in many of these killings likely also involved a STRESS conspiracy to frame the victims. The Wayne County Prosecutor declared all eight of the fatal shootings that involved Raymond Peterson during 1971 to be "justifiable homicides." Each of these incidents is analyzed at length on the "Remembering STRESS Victims" page and summarized only briefly here.

- Herbert Childress (May 11, 1971), a 35-year-old African American male, shot and killed by Patrolman Peterson acting as decoy inside a private apartment during a prostitution sting operation after Childress allegedly attacked the officer with a knife.

- Clarence Manning, Jr. (May 29, 1971), a 25-year-old African American male, shot and killed by Patrolman Peterson acting as decoy backup from a distance of less than five inches away, contrary to his statement. In 1975, the city of Detroit settled a wrongful death lawsuit in recognition that a jury would find that the STRESS team used excessive force and lied about the encounter.

- Horrace Fennicks and Howard Moore (July 5, 1971), a 28-year-old African American male and a 32-year-old African American male, respectively, shot in the back and killed by Patrolman Peterson and another STRESS officer acting as decoy backup while both men fled the scene of an alleged mugging. The STRESS team 'discovered' a knife on the victims. The city of Detroit later settled wrongful death lawsuits by both families.

- James Smith (July 14, 1971), a 32-year-old African American male, shot and killed by Patrolman Peterson and other STRESS officers acting as decoy backup after allegedly being part of a group that tried to mug the decoy with a knife. The wounded survivors testified in the STRESS lawsuit that Smith was an innocent bystander and that the decoy team had initiated the attack and fabricated the entire encounter.

- James Henderson (September 9, 1971), a 24-year-old African African male and eyewitness to Raymond Peterson's previous killing of Herbert Childress, shot and killed by Peterson and another STRESS officer inside a hotel after allegedly attacking them with a knife. The hotel clerk testified in the STRESS lawsuit that Peterson and his partner executed James Henderson in an act of premeditated murder.

- Neil Bray (November 13, 1971), a 21-year-old African American male, shot and killed by Patrolman Peterson and other STRESS officers acting as decoy backup, after he allegedly attacked Peterson with a knife while fleeing from the decoy officer, who shot him from point-blank range in the chest in an act that the STRESS lawsuit labeled an "execution."

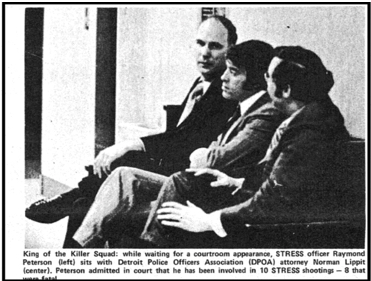

In May 1972, the Legal Defense Coalition named Raymond Peterson and other STRESS officers as defendants in its conspiracy lawsuit and accused him of having "murdered innocent people," specifically including Clarence Manning, James Henderson, and Neil Bray. The anti-STRESS movement turned Peterson into the deadly face of the STRESS unit and labeled him "King of the Killer Squad" (right). The LDC called Peterson as a witness on the first day of the trial and walked him through admissions that he had shot ten men during undercover operations. Then, when the defense attorney asked how many brutality complaints had been filed against Patrolman Peterson by citizens, he mocked the inquiry. "It may have been three, may have been more," Raymond Peterson responded. "Could have been more than three but less than a million."

The Murder of Robert Hoyt and Acquital of Raymond Peterson

Patrolman Raymond Peterson did not kill any additional African American males in undercover STRESS operations after November 1971, at least none documented in available archives, probably because the DPD responded to the anti-STRESS protests by scaling back the decoy technique and assigning its most notorious officer to different tasks (the department kept undercover assignments a closely guarded secret). Then, in March 1973, Patrolman Peterson burst back into the news in dramatic fashion after his fatal off-duty shooting of Robert Hoyt, a 24-year-old African American male. The anti-STRESS movement held three separate protests at DPD headquarters in the week after the incident, labeling him "Mad Dog Peterson" and demanding prosecution for murder. Before his coverup unraveled, Peterson told the Detroit News that he didn't "like taking another man's life, but it seems that I am a magnet for trouble."

There is indisputable evidence that Raymond Peterson fabricated his account of the Robert Hoyt incident and attempted to frame the deceased victim by planting a knife that the officer had brought to the scene of the crime. Forensic evidence proved that Peterson had been carrying the knife around in his pocket for at least a week, a clear illustration of the practice of many DPD officers to have "drop" weapons at the ready to justify an unjustified shooting. Peterson himself even admitted to making up the knife story as part of a risky but successful strategy as a trial defendant, after the Detroit Police Lab disproved his cover story and the Wayne County prosecutor charged him with second-degree murder.

Robert Hoyt Incident. The encounter began around 6:00 a.m. on March 9, 1973, when Robert Hoyt and Raymond Peterson allegedly were involved in a "sideswipe" car accident on the Fisher Freeway shortly after the officer had gone off duty and was driving home. Peterson, who was driving an unmarked car, claimed in his report that Hoyt caused the accident and then illegally fled the scene. Peterson and his off-duty partner, Patrolman Gary Prochorow, who was somehow (and suspiciously) also on the scene in a separate personal vehicle, then chased Robert Hoyt down and shot at him several times from their moving vehicles. Raymond Peterson claimed that he finally managed to pull Robert Hoyt over but then had to shoot him dead because Hoyt first appeared to be reaching for a gun and then jumped out of the car and attacked the officer with a knife, slashing his jacket. Hoyt was actually unarmed, and after shooting him, Patrolman Peterson 'discovered' a knife at the scene--just as he had in so many of his previous fatal shootings.

Patrolman Peterson's account of the Hoyt shooting was deeply suspicious even before the forensic evidence proved that he had planted the knife on the victim. Robert Hoyt's family and coworkers immediately denied that the 24-year-old, who had been on the way home from his job on the night shift at an automobile plant, could possibly have been carrying a knife. Relatives also accused the DPD investigation of covering up the evidence that his impounded car showed no signs of a "sideswipe," as Peterson claimed. His brothers also told the Michigan Chronicle that different STRESS units had continually harassed Robert Hoyt in the weeks before his death, which they speculated might have been because he was driving a used car that he had recently purchased from a known drug dealer. This raises the tantalizing possibility that what happened might not have been an off-duty police officer reacting with rage to a fender-bender but instead a targeted killing by a corrupt cop, perhaps even related to the extensive DPD complicity in the narcotics market and the Black community accusations of direct STRESS involvement (no specific evidence has emerged linking Peterson to narcotics corruption). Another possibility raised in the subsequent investigation was that Patrolman Peterson and Robert Hoyt might have been involved with the same African American woman and that the officer could have instigated the encounter for that reason. Several of Hoyt's friends told reporters that the two men had "hung out in the same bars" and previously argued over the woman, raising the possibility of a revenge hit by the off-duty officer that morning.

On March 22, the Wayne County Prosecutor charged Patrolman Peterson with second-degree murder after the Detroit Police Lab uncovered evidence that the knife that he claimed to have found on Robert Hoyt's body had cat hairs and fibers traceable to the officer's own pet and jacket pocket. The discover was made by Mary Jarrett Jackson, an African American scientist in the DPD crime lab who went on to become the department's first female deputy chief. Prosecutor William Cahalan stated that Patrolman Peterson had shot Robert Hoyt in anger after the automobile worker accidentally rear-ended the officer's vehicle, and so the charge would be second-degree murder because the result was not premeditated. Cahalan declined to charge Peterson's partner, Gary Prochorow, even though the forensic evidence revealed that he had shot Robert Hoyt in the wrist during the car chase. The DPD removed both officers from the STRESS unit and suspended Peterson pending trial.

Trial and Acquital. Raymond Peterson's second-degree murder trial took place in early 1974, soon after the abolition of STRESS by Coleman Young, Detroit's new African American mayor. Peterson's counsel from the DPOA union, Norman Lippitt, opened the defense by admitting that his client had lied about Robert Hoyt attacking him with a knife but insisted that the officer had done so because "he actually felt his life was in danger." The DPOA attorney then took the extraordinary step of blaming Peterson's actions on the higher-up officers who designed STRESS and then "hid" in their offices while tough patrolmen such as Raymond Peterson "have to go out into the streets and deal with robbers, muggers, pimps and prostitutes while laying their lives on the line." Peterson then testified that DPD commanding officers had pressured the STRESS decoy squads to act more aggressively after the first few quiet months of early 1971 and then "congratulated us" whenever they shot and killed supects. During the cross-examination, Peterson broke down crying when confronted with the evidence of his fabrication of Robert Hoyt's knife attack but insisted that he had feared for his life on the side of the highway that morning. Peterson said, through sobs:

Peterson's partner, Gary Prochorow, also testified that Robert Hoyt had threatened both of their lives by driving so recklessly that "I actually thought the man was trying to kill us." Given that both officers were actually chasing Hoyt down the freeway at high speed, this witness testimony under oath seems like an obvious lie, designed to buttress the self-defense claim. In closing arguments, defense counsel Lippitt again blamed the DPD hierarchy for Hoyt's death, insisting that Raymond Peterson was "given a gun by an ignorant bureaucracy, and when he used it with fatal results, was lauded and praised by narrow-minded, non-thinking superiors." Peterson's attorney also blamed the criminality of Black Detroit for Peterson's actions in barely veiled racist language: "He was conditioned by the cruelty in the streets of this city, by the hate that permeated the very air we breathe."

In his instructions to the jury, Judge Joseph Maher arguably prejudiced the verdict by requiring them to evaluate Peterson's actions under the 'reasonable discretion' standard for use of force by law enforcement officers, rather than the stricter standard for regular citizens, even though the policeman had been off duty and in his private car at the time of the incident. The judge told the jurors that in assessing Peterson's own state of mind, if he "reasonably believed that Robert Hoyt was about to do him great bodily harm, you are required to find the defendant not guilty." The jury, made up of 12 white members and 2 African Americans, then proceeded to acquit Raymond Peterson of second-degree murder.

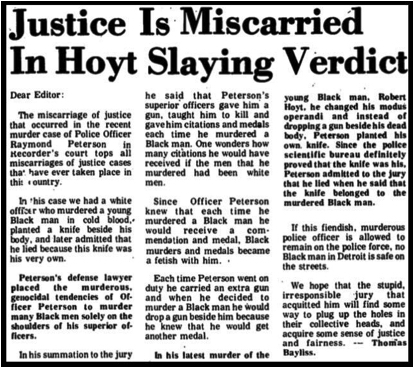

African American residents of Detroit expressed outrage after Raymond Peterson's acquital but also a profound sense of inevitability based on the traditional deference of white jurors toward police officers who killed Black citizens. The Michigan Chronicle reported at length on the anger and shock in the Black community and also emphasized that the defense counsel had disqualified many African Americans in order to obtain a mostly white jury pool of city residents predisposed to sympathize with the police. The Chronicle additionally ran commentary by enraged Black citizens such as Thomas Bayliss (right), who emphasized that Peterson had once again gotten away with murdering "a young Black man in cold blood." Bayliss dramatically labeled the verdict the greatest "miscarriage of justice" in the history of the United States.

Even Prosecutor William Cahalan, who had accepted with equanamity the acquitals of the police officers in the only other STRESS-related prosecution, the Rochester Incident trial, expressed dismay and confusion as to how "the jury could reach that verdict." And even the Detroit Police Department, which had almost always welcomed back officers who were charged with felonies but then acquitted, terminated Raymond Peterson after an internal Trial Board proceeding. The DPD's decision to punish a highly decorated STRESS officer after his ninth killing of an African American citizen was presumably based on Peterson's admission of lying in his incident report, but probably also not unrelated to his eagerness on the witness stand to blame commanding officers for his two-year killing spree.

Postscript

In 1976, the Detroit Free Press published a lengthy profile of fired STRESS officer Raymond Peterson, shortly after he successfully took the Detroit Police Department to arbitration to receive two years of back pay and a disability pension. The article portrayed Peterson as a friendly middle-aged man, with the "eyes of a playful cat that suddenly purrs for affection." The working-class Detroit native was now working as a truck driver, but five years before he had been "a hero to the officials of the Detroit Police Department," an elite policeman and killer who "was doing exactly what he was conditioned and trained to do."

Looking back, two years after his acquital for the murder of Robert Hoyt, Peterson reiterated his racist description of the Black neighborhoods of the city of Detroit as more dangerous than a jungle and their residents as more depraved than wild animals. "It's worse than a jungle on those streets," Peterson insisted, "because in a jungle the animals they just kill for food, but on those goddamn streets, boy, they will kill you just for kicks." Raymond Peterson then justified his own track record of deadly violence--he almost certainly killed more people than anyone else, whether police officer or civilian, in modern Detroit history--by drawing an ultimately murky distinction between the righteous side of the law versus the unwritten rules of the streets. "When the line comes down to push or shove and you got the hammer," the white man responsible for the deaths of nine African American men explained, "you got to use it because chances are you aren't going to get another chance."

Peterson then argued, rightly, that his superiors in the Detroit Police Department were also responsible for his actions, having designed and celebrated the lethality of the STRESS operation and repeatedly praised and rewarded him personally. "I really believed I was doing the right thing," the truck driver recalled. "We were cutting down on crime. They [the DPD hierarchy] were happy with me. Whenever I shot someone, I would have to go to headquarters to fill out a report and the guys would cheer me when I walked in. . . . The brass in the department went out of its way to encourage me."

Raymond Peterson sought absolution but also ended the profile with a lingering question: "Was I right in what I did because that's what I was told to do?"

Sources:

Michigan Department of Civil Rights, Community Relations Bureau, RG 83-55, Michigan State Archives

Michael Graham, "STRESS Decoy Defends His Violent Role," Detroit Free Press, Dec. 19, 1971

Robert M. Pavich, "STRESS Officer Says He Attracts Trouble," Detroit News, March 14, 1973

Tom Ricke, "The Man with the Flash-Card Gun: Raymond Peterson since STRESS," Detroit Free Press, Sept. 12, 1976

Detroit Free Press, April 28, May 2, 1972, March 23, 1973, Aug. 27, 1976

Michigan Chronicle, May 6, 1972, March 17, 24, 1973, Feb. 23, March 2, 9, 16, 23, 1974

Howard Kohn, "Terror In the Streets: Detroit's Super Cops," Ramparts (Dec. 1973), 38-41, 55

Toni Swagner Papers, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University