Domestic Violence & Sex Crimes

“Domestic violence was not what [the police] saw as a ‘glorious crime’… ‘locking a guy up in his home, for beating up his wife, who is his property.’ That was the mindset.” – Former Detroit Police Chief Ike McKinnon

Under-policing of Domestic Violence and Sex Crimes

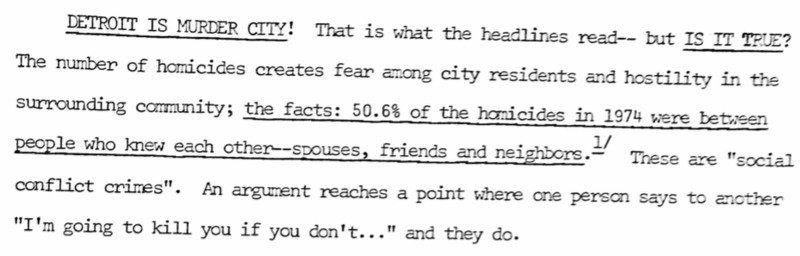

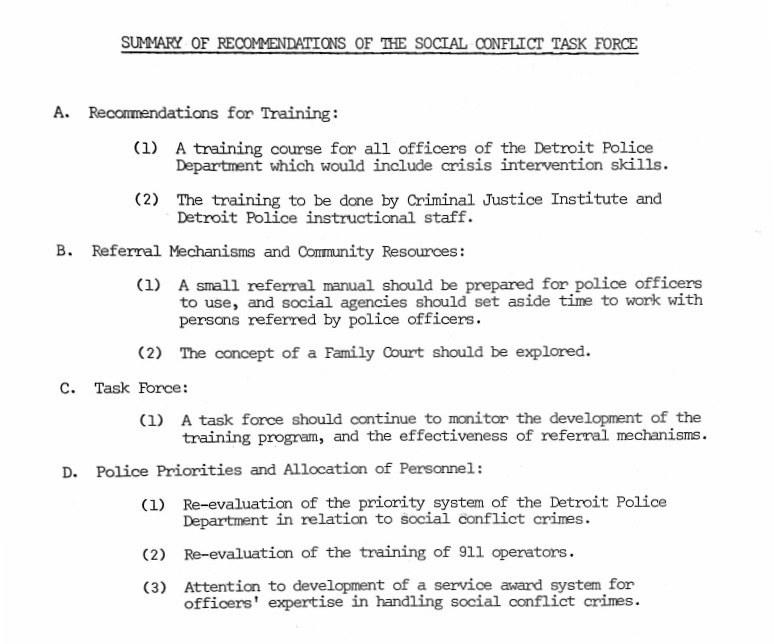

During the 1970s, the Detroit Police Department faced pressure from local feminist organizations and women’s groups to reform its practices around domestic violence and sex crimes. Local media drew attention to the desperate circumstances of many abused women and the lack of legal recourse available to them. In 1974, the Detroit Police Department reported that more than half of homicides were due to personal social conflict, debunking the perception that stranger-crimes predominantly accounted for the danger of violence in Detroit. The Social Conflict Task Force (SCTF), a commission under the DPD tasked with researching and developing training for policing social conflict, released a report of their findings in 1974. In this report, the SCTF claimed that a large number of homicides in Detroit result from conflicts like interpersonal arguments between people that know each other, often within the home. The SCTF was especially concerned with one type of social conflict within the home—domestic violence. Because police were the first responders of social conflict, untrained police often escalated the conflict, killing some citizens on arrival. Importantly, the task force pointed out that these tensions especially affected the “poor, under- or unemployed,” and Black citizens.

This pattern held true for sexual assault, as well. The DPD reported in 1974 that one-third of all rapes committed in the state of Michigan occurred in the city of Detroit, and 74% of victims were Black. The pressing reality of these crimes did not mean that law enforcement prioritized them, however.

In Detroit, a complacent attitude towards and trivialization of violence against women manifested in systemic under-policing of domestic violence and sexual assault cases. Former Police Chief Isaiah McKinnon, who served in the Detroit Police Department (DPD) for over 20 years, witnessed the disregard for domestic violence prior to institutional reforms of domestic violence policing. In the interview below, McKinnon discussed the limited training that officers received to respond to domestic violence calls. When asked how seriously the Detroit Police Department took domestic violence, McKinnon said “it wasn’t, it wasn’t taken seriously.”:

“A man could beat his wife up and very little was done… When we were young officers, they told us that… if you responded to a place where there was domestic violence, you take the guy out of the house and take him for a ride.” McKinnon detailed how young officers were told to drive “the guy” (perpetrator of domestic violence) to Belle Isle and make him walk home. “We had no training, no training.”

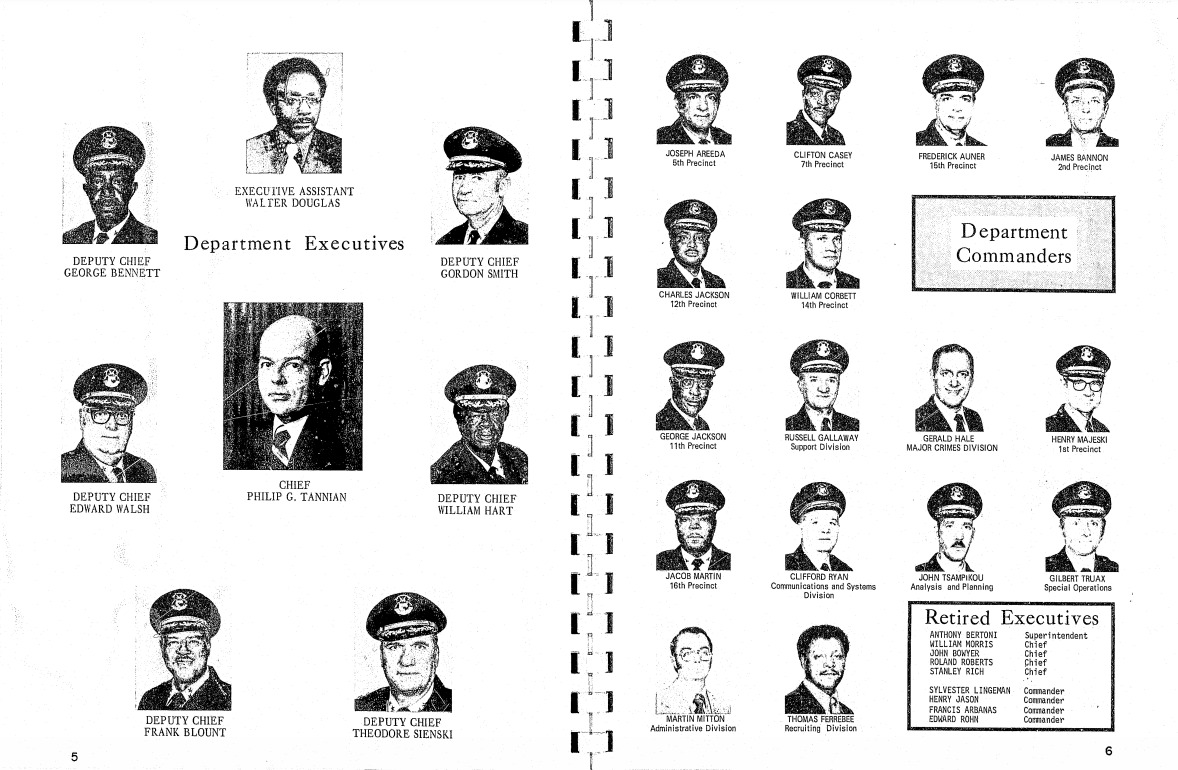

McKinnon explained that when he took over the Sex Crimes Unit in 1975, there were no laws dictating the treatment of domestic violence by the police. He mentioned Deputy Chief Bannon’s work with the state to get a law passed to require police departments to act against domestic assault.

Former DPD Chief Ike McKinnon on Domestic Violence (7:46 to 9:34)

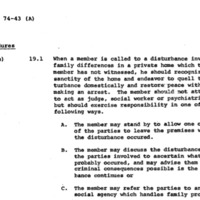

Evidently, disregard for rape and domestic violence victims was the Department’s official policy. As stated in the DPD’s General Orders in 1978: “Family trouble is basically a civil matter. It is not a police function to arbitrate or undertake negotiations in marital difficulties.” Arrest protocol instructed officers to “recognize the sanctity of the home and endeavor to quell the disturbance domestically and restore peace without making an arrest.” The insistence on police inaction in cases of domestic violence prompted calls to directly amend arrest procedures and have domestic abuse treated as any other crime.

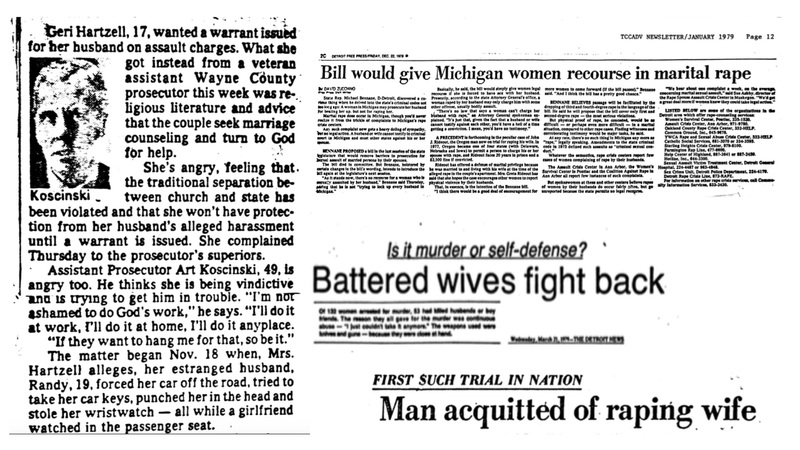

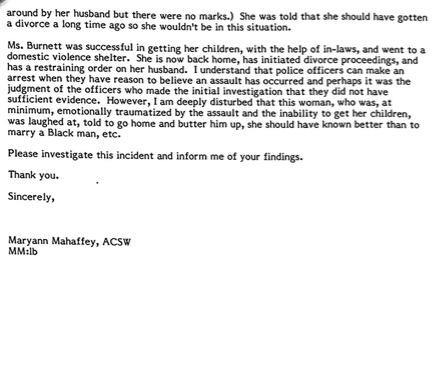

Local feminist organizations and women’s groups in Detroit mobilized in the 1970s to bring attention to the mistreatment of domestic violence victims and pressure the police to change. The Tri-County Coalition Against Domestic Violence was a group of individuals and organizations that worked to address domestic violence in Detroit and help victims. Included in a Tri-County Coalition Against Domestic Violence Newsletter published in January 1979 was a December 1978 article from the Detroit Free Press titled “Wife asks for arrest and gets advice.” The article describes the situation of a Detroit woman who wanted a warrant for her husband’s arrest on assault charges. When the police arrived, an officer gave her religious literature and lectured her about seeking couples counseling to save the marriage. While the woman eventually obtained a warrant, this case serves as a prime example of neglect in domestic violence policing in Detroit.

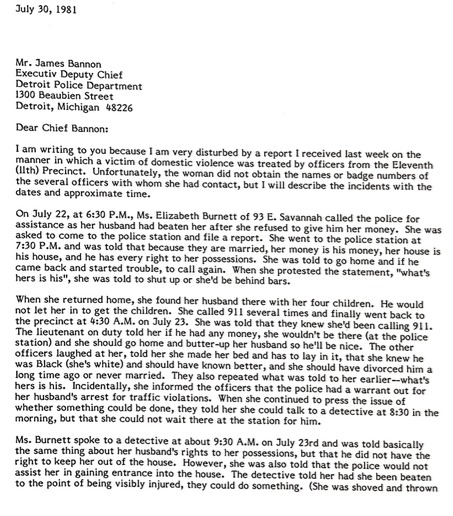

In a 1981 case detailed in a report sent to Detroit City Councilwoman Maryann Mahaffey, a public servant dedicated to social welfare and gender equality, a female victim of domestic assault called the police on her husband who had beaten her for refusing to give him money. When she went to the police station to file a report, she was told that because they were married, he had a right to her possessions. She was then told to go home and call again if there was any further trouble. Upon returning home, her husband refused to let her into the house. After calling 911 several times, she returned to the precinct at 4:35 AM. The officer on duty told her that she should go home and “butter-up her husband so he’ll be nice.” Other officers laughed at her, telling her that because she was white and her husband Black, she “should have known better” and never married him in the first place. The next morning, she was told that police could not help her because she had not been beaten to the point of visible injury. Councilwoman Mahaffey requested that Deputy Police Chief Bannon investigate this incident, but the findings are unknown.

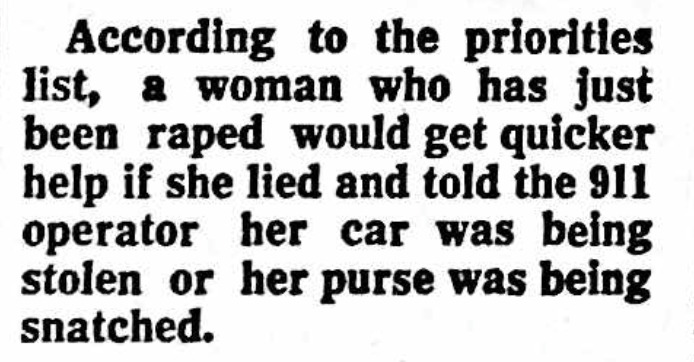

The Second-Wave Feminist Movement and Victimized Women

Prior to the feminist movement of the 1970s, the criminal legal system ignored, if not downright tolerated, domestic violence. The legal system operated on the basis that women were property of their husbands, priming judges, prosecutors, and police officers to treat cases of domestic violence as noncriminal “disturbances.” Accordingly, police officers were trained to avoid intrusion on the private affairs of spouses. Due to the noncriminal nature of these cases, officers were instructed not to make arrests, even when victims—overwhelmingly women—suffered injuries. Consequently, the DPD considered domestic violence calls low priority and police response was severely delayed, if it came at all.

Additionally, police officers severely under-enforced existing, albeit sexist, rape statutes. Prior to the 1970s, many state sexual assault laws contained corroboration, resistance, and reporting requirements, as well as inquiries into the sexual history of the claimant. Most of these requirements were rooted in misogynistic myths about the reliability of women’s accusations. The policing of sexual assault reified these sexist norms. Police officers could refuse to follow up on rape complaints, or intimidate women into not reporting sex crimes.

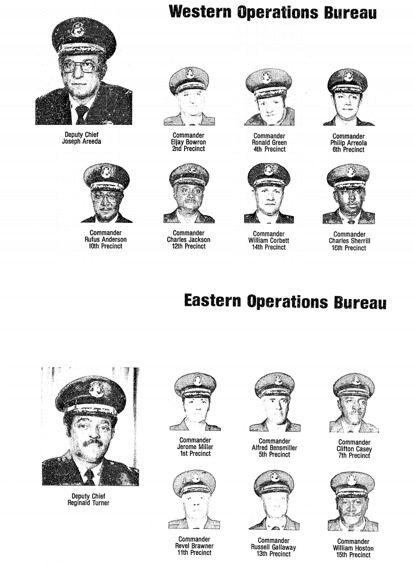

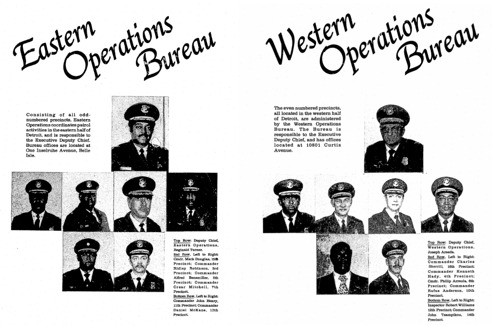

The under-prioritization of crimes against women might not come as a surprise given that absence of women in positions of authority. The department’s annual reports reveal the glaring lack of gender diversity in policymaking decisions within the DPD:

Until the mid-1970s, women were confined to the Women and Children’s Division, where policewomen acted as caseworkers, reviewing criminal and non-criminal complaints concerning female and children victims of sex crimes and preparing cases for prosecution. Policewomen were expected to attend to the social problems of individuals involved in these cases, and their work was largely clerical. The treatment of crimes against women began to change somewhat with the establishment of a formal Sex Crimes Unit in 1974. Additionally, at the urging of female city council members and the National Organization of Women, the Rape Counseling Center was placed under the auspice of the DPD in 1977, two years after its founding.

Changes in attitudes towards domestic violence cases is largely attributed to the work of feminist organizations, both locally and nationally. Pressure from feminist community action did result in significant institutional change in police departments around the country, but the process was slow and uneven. Eventually the establishment of the DPD Sex Crimes Unit would bring these issues to the forefront, as well. However, the disregard for gendered and sexual violence created an environment that turned a blind eye to officers who perpetrated these crimes on citizens.

SOURCES:

Aya Gruber, "ARTICLE: The Feminist War on Crime," Iowa Law Review, 92, 741 (March, 2007). https://advance-lexis-com.proxy.lib.umich.edu/api/document?collection=analytical-materials&id=urn:contentItem:4NX3-KBW0-02BM-Y0J4-00000-00&context=1516831.

Detroit Police Department Women's Division, n.d., Box 9, Folder 11, William G. Milliken Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

Detroit Police Department Women's Division (2), n.d., Box 9, Folder 11, William G. Milliken Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

Detroit Police Department Women's and Children's Division, "Rape; A Brief Profile," 1974, NCJRS.gov

Emily J. Sack, "ARTICLE: BATTERED WOMEN AND THE STATE: THE STRUGGLE FOR THE FUTURE OF DOMESTIC VIOLENCE POLICY," Wisconsin Law Review, 2004, 1657 (2004). https://advance-lexis-com.proxy.lib.umich.edu/api/document?collection=analytical-materials&id=urn:contentItem:4FS1-4080-00CW-H09K-00000-00&context=1516831.

Lt. John A. Clark, “Evaluation of Crisis Intervention Grant Program,” (May 5, 1978), Box 1, Diana Warshay Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

"Social Conflict Task Force Report," (Oct. 28, 1974), Box 40, Folder 1, Maryann Mahaffey Papers, Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library

Testimony of Althea M. Grant, Director of the Rape Counseling Center of the Detroit Police Department and President of the Southeastern Michigan Anti-Rape Network, United States Congress. House. Committee on the Judiciary. Subcommittee on Criminal Justice, Hearings Before the Subcommittee on Criminal Justice of the Committee on the Judiciary, House of Representatives, Ninety-eighth Congress, Second Session, on H.R. 2661, H.R. 2978, H.R. 3498, and H.R. 5124, (February 2, 7, March 15, 22, April 2, and August 2, 1984), GPO: 1985.

Wayne State University. “The Maryann Mahaffey Movement: Memorializing a Detroit Social Justice Pioneer.” School of Social Work. Accessed December 21, 2019. https://socialwork.wayne.edu/news/the-maryann-mahaffey-movement-memorializing-a-detroit-social-justice-pioneer-36731.