Crime Under STRESS

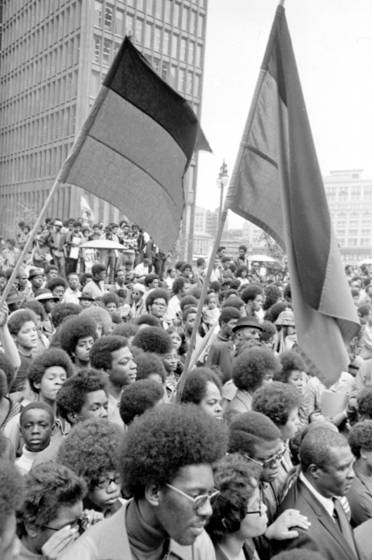

The Detroit Police Department claimed that the STRESS program had immediately and dramatically reduced street crime in Detroit through its "proactive policing" and undercover decoy and surveillance methods. Commissioner John Nichols doubled down on his public defense of STRESS as an effective program of crime deterrence in response to the protests that began in September 1971 after an officer in the unit shot and killed two unarmed black teenagers alleged to be muggers. The DPD and the Gribbs administration consistently made this case during the early 1970s through a public relations offensive evident in official reports, in community forums, and in their combative responses to investigations by the city council and the U.S. Congress. These claims of STRESS's effectiveness had important implications, as discussed below, especially in convincing a substantial subset of African Americans and moderate civil rights groups such as the Detroit Urban League to support the program in its initial phases.

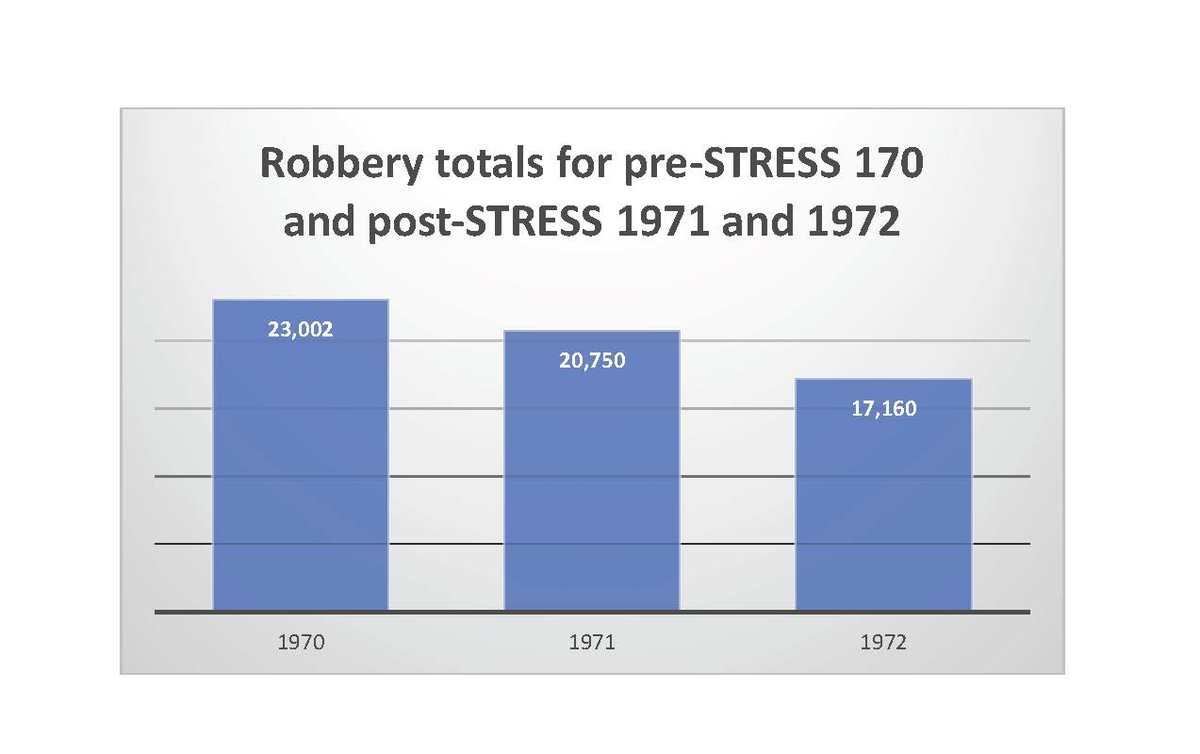

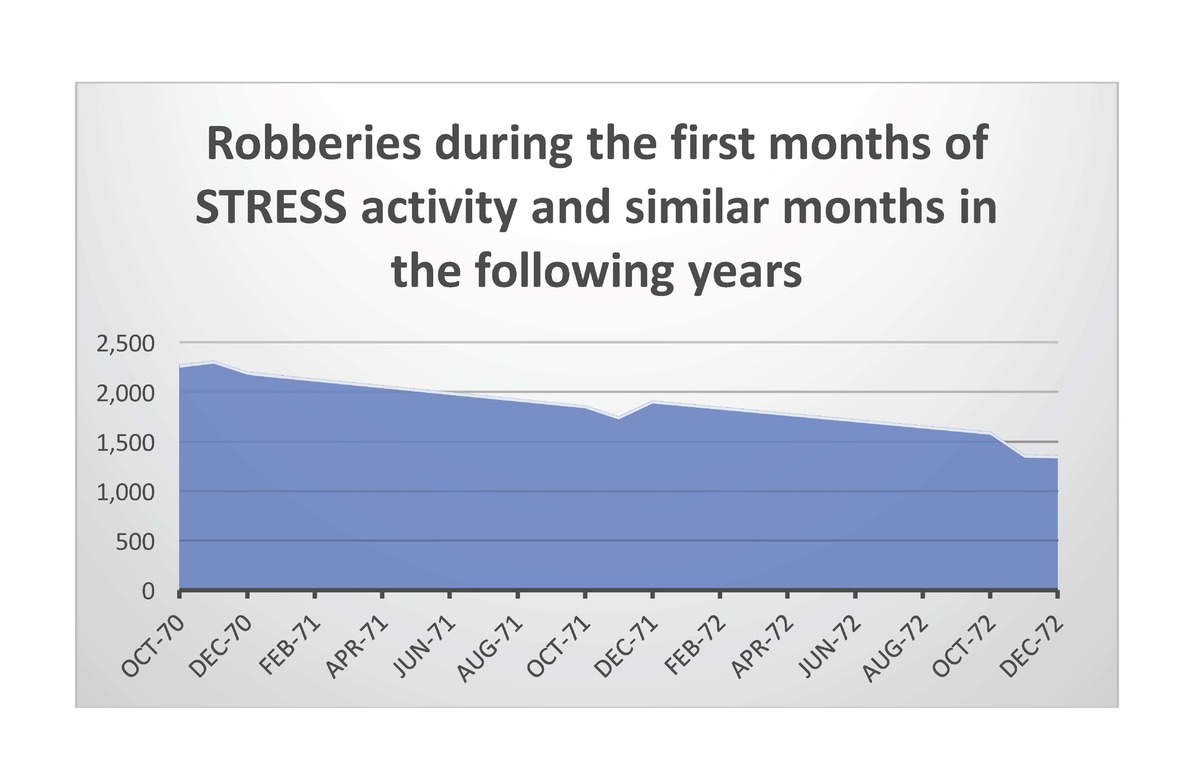

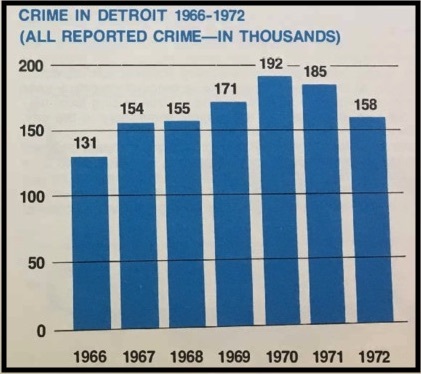

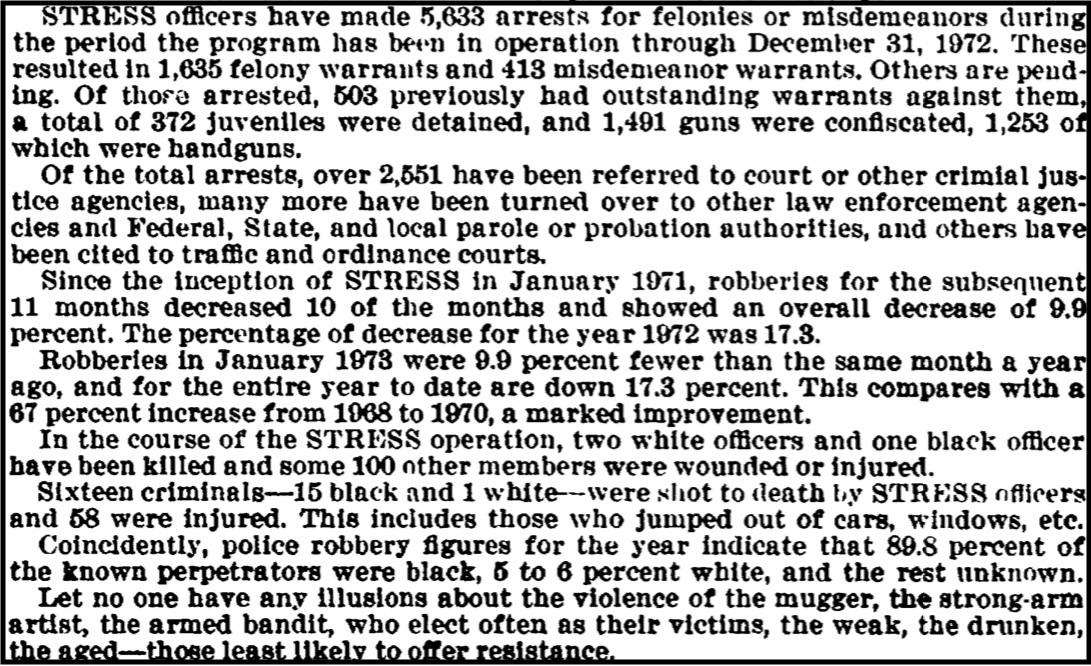

Commissioner Nichols championed STRESS for accomplishing its stated purpose by citing a reduction in the annual number of robberies by almost 6,000 between 1970 and 1972, a first-year decline of 9.9% and a second-year decline of 17.3% (right). The DPD commissioner knew that this reduction in robberies could not be proved to have been caused by STRESS and almost always made the case by implication and through correlation, by linking the STRESS data and the robbery data constantly in public discussions. The DPD also reported that STRESS officers, who represented just a small fraction of the police force on patrol, had confiscated 1,253 guns during 1971-1972 as well as a relatively minor quantity of illegal drugs. The DPD further reported that 89.8% of robbery perpetrators were black, with the remainder split between white and race unknown.

There is no way to verify, and many reasons to doubt, the DPD's public insistence that STRESS had reduced street crime, as Commissioner Nichols and STRESS architect James Bannon themselves conceded in a 1972 article intended only for a law enforcement audience. "There is no objective way," they wrote, "to prove conclusively that STRESS was responsible for some or all of the decrease" in robberies. The DPD leadership was only acknowledging a statistical truth about uncertainty, but there are additional reasons to be skeptical of official crime data. Crime statistics are notoriously unreliable and suspectible to political manipulation, as many STRESS critics emphasized. In its "Detroit Under STRESS" expose, the radical group From the Ground Up cited academic scholarship finding that most urban police departments reported "doctored statistics and outright lies" in order to receive additional federal crime control grants and to convince politicians and the general public that their aggressive methods were effective.

The gallery below provides graphs created by our team that illustrate the DPD's official data on robberies and gun confiscations between 1970 and 1972, along with a DPD chart claiming a reduction in the total crime rate during this period. This data is not reliable as a measurement of actual crime, as explained below.

The Unreliability of Crime Data

In February 1973, an African American grandmother named Meneco Hitt wrote a letter of complaint (at right) asking what could be done about the "harassment being conducted by the WHITE POLICEMEN toward the colored people of Detroit." She told a story of her grandson David playing with his dog in the yard when two white police officers frisked him, found his house keys, accused him of stealing a car, and detained the boy until a white neighbor intervened and demanded his release. During the incident, four more squad cars rushed to the neighborhood, and the officers arrested two other black teenagers for the alleged car theft. Mrs. Hitt drew two conclusions from the encounter: 1) "instead of teaching the young people to respect an officer, they are learning to hate them," and 2) the DPD was trumping up charges against "innocent citizens" in order to "make a certain quota to make the public believe they are combating crime."

The Detroit Police Department manipulated crime data to suit its political agenda, frequently hyping a "wave" of violent and serious crime in black neighborhoods to justify get-tough crackdowns, and then periodically asserting that the crime rate was back under control in order to convince the public that militarized policing worked. In a 1973 public relations offensive, the DPD claimed that all reported crime had dropped dramatically in the city of Detroit from 1970 to 1972, from 192,000 to 158,000 incidents citywide, because of the STRESS program and other aggressive and effective tactics (gallery, above right). The DPD specifically reported that STRESS units had made 5,633 arrests, including 372 of juveniles, and confiscated 1,491 guns (large excerpt below). These numbers, like the subset of robberies attributed to STRESS and like all crime data, are unreliable and easily distorted for the political agendas of law enforcement agencies:

- First, police departments base crime statistics on victim reports, which understate the actual crime rate because many people do not call the police, particularly in the case of muggings and small-scale theft, and especially in low-income and nonwhite communities with deep distrust of law enforcement and a long history of underpolicing as well as overpolicing. STRESS began at a time of already very high levels of dissatisfaction and fear of the police by African American residents of Detroit. It is entirely plausible and even likely that African American residents became even less willing to report robberies and similar crimes to the DPD as the extreme violence of the STRESS unit became public knowledge and as black community protests against its methods escalated. This dynamic would bring the perverse effect of making it seem like the DPD was better protecting black citizens through a reduction in measured street crime when its violent and deadly methods were actually making their neighborhoods less safe, from robberies and law enforcement brutality alike.

- Second, police departments base crime statistics on total arrests, but this is not an accurate proxy for "crime" because of racial profiling and other forms of discretionary criminalization, meaning that law enforcement agencies arrest far more people than are ever prosecuted or ultimately convicted (and even convictions, usually based on plea bargains, are not clear evidence of "crime"). Commissioner Nichols boasted that STRESS had resulted in 5,633 total felony and misdemeanor arrests in its first two years of operations, but only 2,048 (36%) of these arrests had resulted in arrest warrants when he gave this testimony in the spring of 1973. Arrest warrants issued by a judge require a lower evidence threshold and are not the same thing as prosecutorial charges, or convictions. Nichols did not even provide data for what percentage of these arrest warrants resulted in either charges brought by prosecutors or convictions in court. The DPD commissioner also cited gun confiscations without ever specifying which percentage of these were actually illegal. In numerous cases, the DPD arrested African Americans for illegal gun possession when they had valid concealed weapons permits, meaning that the police through racial criminalization falsely turned law-abiding citizens into 'criminals' in the overall statistics.

- Third, and most problematic for the DPD's claims, the serious violent crime rate for murder and reported rape increased significantly during the same time period that Commissioner Nichols was asserting that STRESS had reduced the street crime rate. In a June 1973 press conference, Nichols boasted that the city's crime rate had decreased by 7% during the previous year and a half, but the DPD's own data also showed a 89% increase in reported rapes and a 14% increase in murders during the same time period. It is worth noting, in evaluting the statistical confusion, that Nichols and Bannon had justified STRESS in the first place by claiming that the out-of-control robbery rate had led to a terrible increase in murders and sexual assaults, and that a police focus on reducing robberies would have a ripple effect and reduce all violent crime. When the statistics on violent crime contradicted this prediction, Nichols and Bannon were silent, and the DPD along with the Gribbs administration praised STRESS for making the city safer while downplaying the increases in murders and rapes (note that sexual assault was still severely under-reported and under-policed during this period).

- The DPD's overall and STRESS crime data do not include any acknowledgment of criminality, brutality, misconduct, and corruption by police officers, which was endemic in STRESS and a serious problem in law enforcement more generally during this era, as detailed throughout this section and exhibit. In fact, as is evident in the excerpt directly below, Commissioner Nichols reported the killings of Detroit civilians by STRESS officers as one of the unit's accomplishments in making the streets safer and protecting law-abiding citizens from violent criminals. By 1973, many black citizens and most African American organizations instead had concluded that STRESS officers were themselves dangerous criminals who threatened public safety and civil liberties.

Crime Politics and Public Support for STRESS

The architects of STRESS, especially Commissioner John Nichols and Detective Inspector James Bannon, constantly claimed that the main goal of the initiative was to protect law-abiding black citizens from street crime and that, because of its effectiveness, the black community overwhelmingly supported the program. This claim did not rest on clear evidence and instead was, first and foremost, a strategic response to the emergence of the anti-STRESS protest movement in the fall of 1971. There is no question that very large majorities of the white residents of Detroit did support STRESS throughout its existence, and most of them proved this by voting for Nichols when he ran for mayor on a pro-STRESS platform in 1973. The sentiment among African Americans in Detroit was more divided, fluid, and complex.

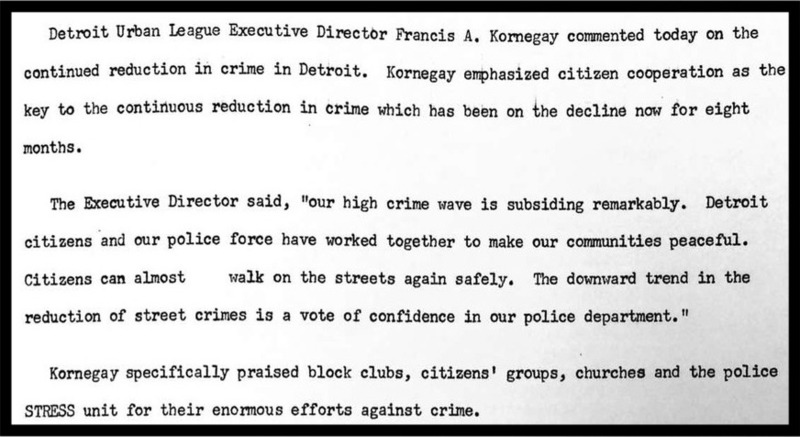

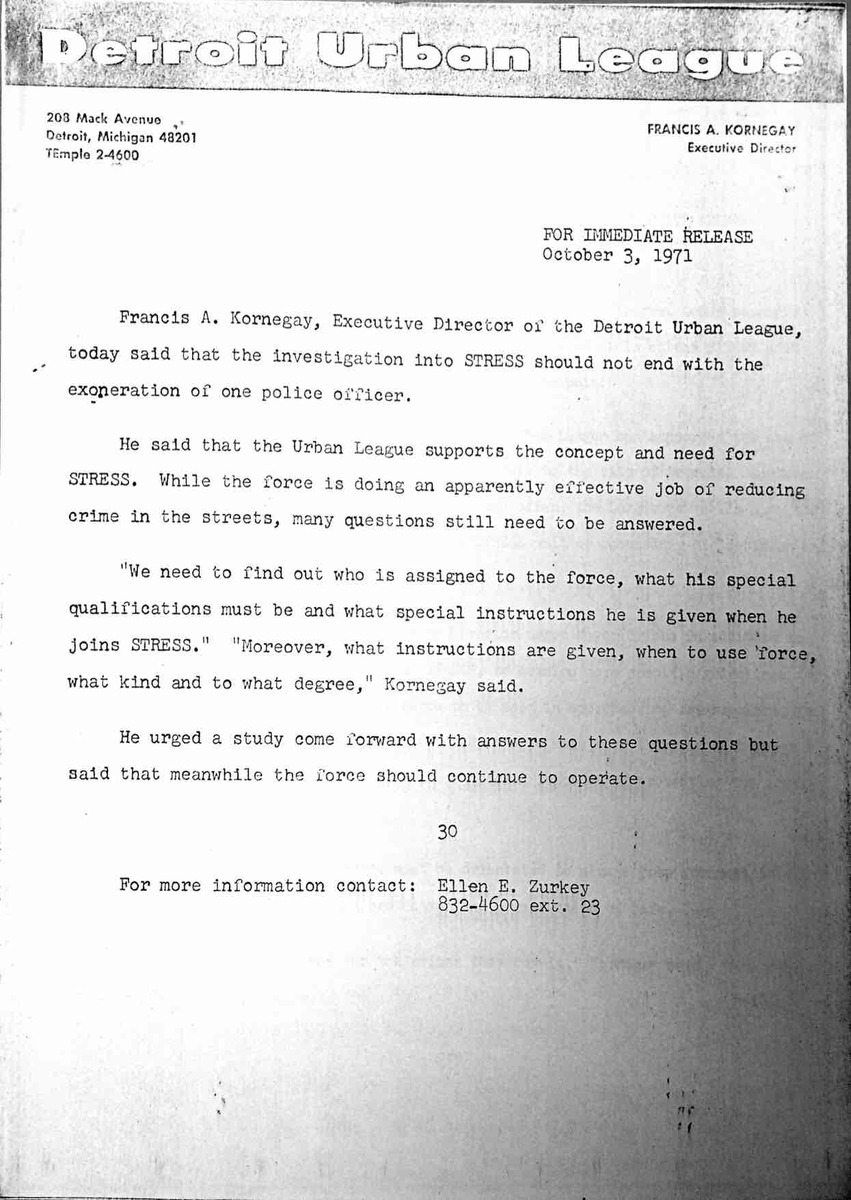

The Detroit Urban League (DUL), the most moderate and pro-business of the mainstream civil rights organizations, vocally supported the STRESS program from the start, while also calling for reforms to its procedures as the number of police killings escalated. The DUL had long pushed for an effective and color-blind war on crime and worked closely with the Detroit Police Department to enhance police-community relations and reduce street crime during the 1960s and early 1970s. Francis Kornegay, the executive director of the Detroit Urban League, issued a statement in support of STRESS in October 1971, after the first wave of protests against the unit's use of deadly force. Kornegay stated that STRESS was "doing an apparently effective job of reducing crime in the streets" (gallery, below left). The Urban League continued to endorse and credit STRESS for making the streets safer during 1972, as the protests against the DPD intensified (right).

The Detroit Urban League rejected the calls to abolish STRESS that were coming from not only black power groups but also the NAACP and other African American civic organizations, instead promoting reforms to maintain the undercover focus on street crimes while lessening the reliance on deadly force. The DUL specifically asked for better psychological screening of STRESS officers, more African American members in the unit, and guidelines to restrict gunfire against people who were unarmed and fleeing. "Muggers should be arrested for the crimes they commit," Francis Kornegay commented in March 1972, "but they should not be killed for them." In 1973, the Detroit Urban League continued to argue that the "overwhelmingly number of residents of the Detroit area" wanted the DPD to keep the streets safe through "color-blind law enforcement," and that the police department administration shared this goal.

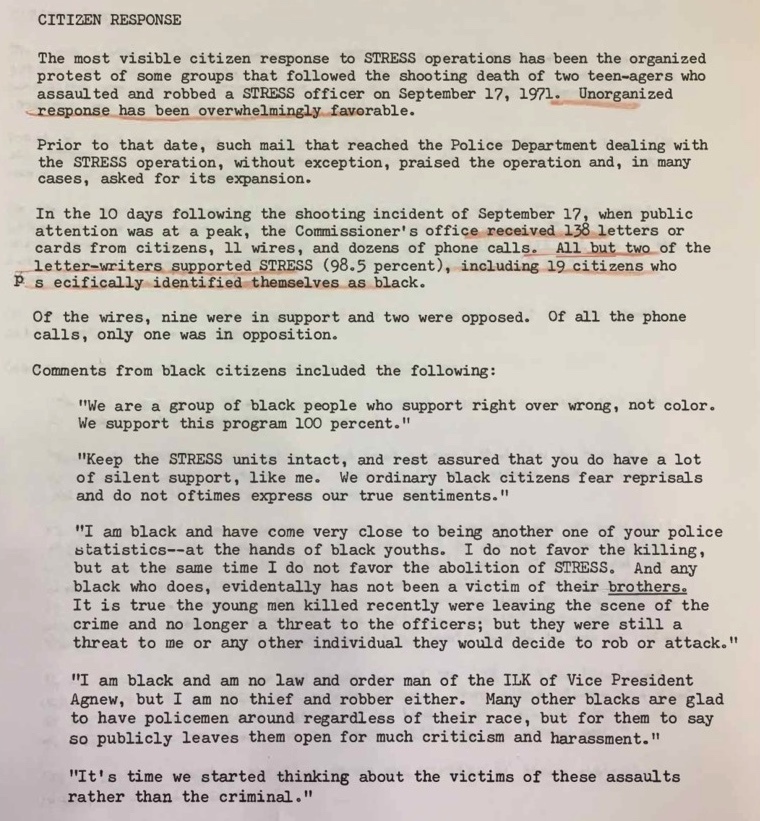

Police Commissioner John Nichols also repeatedly argued that a quiet majority of the black citizens of Detroit supported STRESS. In October 1971, Nichols delivered the DPD's first major STRESS report to the city council in the aftermath of the mass protests that followed the killing of two black teenagers a month earlier (right). At the end of his report, Nichols claimed that the anti-STRESS protesters only represented a vocal minority and that most residents of the city, black and white, supported the DPD's tactics. As evidence, he cited a 98.5% approval rate in the 138 letters that the DPD received during the second half of September. It is crucial to emphasize that these letters are not a representative sampling of community opinion. Most black residents who were critical of the police wrote letters to civil rights groups and black politicians, not the DPD. Most of the pro-STRESS letters were in fact from white residents of the city, indicating that the STRESS program appealed most to white homeowners who feared racial integration and street crime. Nineteen came from black residents, and Commissioner Nichols strategically chose to highlight these voices in his defense of STRESS. His report included these responses:

- "Keep the STRESS units intact, and rest assured that you do have a lot of silent support, like me. We ordinary black citizens fear reprisals and do not oftimes express our true sentiments."

- "I am black and have come very close to being another one of your police statistics--at the hands of black youths. I do not favor the killing [of the two teenagers], but at the same time I do not favor the abolition of STRESS."

- "I was attacked . . . by a group of about eight to ten Negro boys, and was being beaten until rescued by an officer of the STRESS unit."

- "It's time we started thinking about the victims of these assaults rather than the criminal."

Commissioner Nichols also cited a survey conducted by an African American minister revealing that 71.5% of the black residents of a particular neighborhood supported STRESS and 28.5% were opposed. It's also noteable that 73 percent of the Black teenagers in the survey expressed opposition to STRESS, whereas 99 percent of the adults were in favor, indicating a massive generation gap between older African Americans who feared street crime and youth who clearly feared police violence even more. The minister's survey also was not a scientific sampling, and therefore unreliable as a precise gauge of public sentiment. But there is clear evidence that a significant number of black citizens supported the concept of the STRESS unit, at least originally.

There is also clear evidence that African American support for STRESS decreased steadily between the fall of 1971 and the spring of 1973, as the civilian body count rose and other STRESS-related scandals and mass brutality incidents occurred. In May 1973, a scientific poll conducted by the New Detroit Committee revealed the following racial breakdown:

- 65% of black residents of Detroit disapprove of STRESS (May 1973)

- 78% of white residents of Detroit approve of STRESS (May 1973)

Commissioner Nichols's fixation on the alleged pro-STRESS support of black citizens was clearly an effort to defend the initiative by discrediting the community protests that raged against the DPD starting in the fall of 1971 and culminating in the spring of 1973. When the opposition of black citizens became more pronounced, and even scientifically validated in the New Detroit Committee survey, Nichols ignored this evidence of public opposition and continued to claim that STRESS was supported by an overwhelming majority of 'law-abiding' citizens. In a congressional hearing held in spring 1973, Nichols cited the exact same letters from black residents that he had received in the fall of 1971, and the exact same unscientific survey conducted by a black minister from the same time period. Facing hostile questioning from black members of Congress, including U.S. Rep John Conyers of Detroit, Commissioner Nichols continued to insist that most residents of the city supported STRESS and that the program had reduced crime in the streets. The congressional oversight committee strongly disagreed, pointing out that the murder rate had risen significantly in the past three years and arguing that neither the DPD's claims that STRESS had resulted in the reduction of robberies or that "the majority of the black public" in Detroit supported the program rested on verifiable evidence (gallery, below right).

Sources:

Detroit Free Press, June 19, 1973

Detroit Urban League Records, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

Detroit Police Department Additional Papers (1965-1993), Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library

“Street Crime in America: The Police Response,” April 12, 1973, Hearings before the Select Committee on Crime, House of Representatives (Washington: GPO, 1973)

From the Ground Up, "Detroit Under STRESS," 1973, Joseph A. Labadie Collection, Special Collections Library, University of Michigan

Detroit News Photograph Collection, Virtual Motor City, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Detroit Commission on Community Relations (DCCR)/ Human Rights Department Records, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University