STRESS Abolished

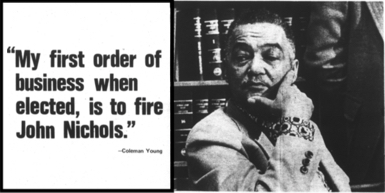

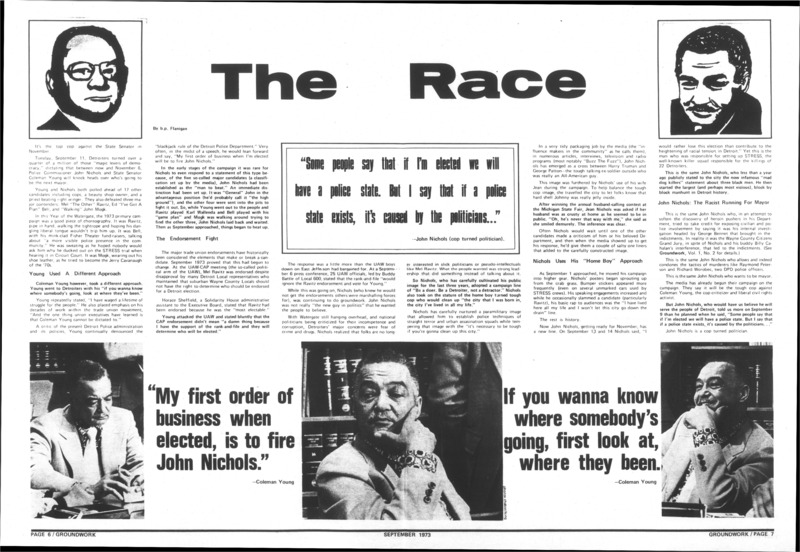

The 1973 mayoral election in Detroit pitted the Black community against the police department. After a crowded primary, the two general election opponents were John Nichols, the DPD commissioner running on a pro-STRESS and crime crackdown platform, and Coleman Young, an African American state senator and longtime critic of DPD racism, brutality, and political repression of civil rights activism. Nichols ran a hard-right campaign aimed at the city's dwindling white residents, acknowledging that "some people say that if I'm elected we will have a police state" and declaring that "it's necessary to be tough if you're going to clean up this city." Coleman Young campaigned on a platform of "law and order, with justice" and promised that when elected he would immediately abolish STRESS, fire John Nichols, and clean up the police department. Young repeatedly labeled the DPD a "racist" organization and called STRESS "an execution squad rather than a law enforcement squad." In a racially polarized election, in a city approaching a Black majority, Coleman Young narrowly defeated Nichols and then abolished STRESS soon after he was inaugurated.

The "Abolish STRESS" Campaign and the 1973 Election

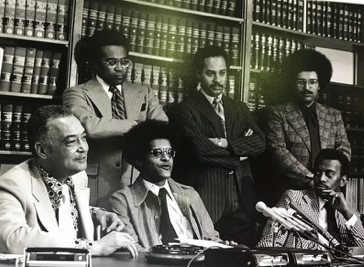

Black and white radicals in the anti-STRESS movement continued to hold protests and rallies during 1973, building on the momentum of the Black community backlash against the abuses of the DPD manhunt and the Independent Black Commission's trial of STRESS before a people's tribunal. The Coalition to Abolish STRESS, the organization that grew out of the Police Terror Commission hearings, organized multiple rallies and pickets of DPD headquarters, with significant participation from students at Wayne State University (right). Maceo Dixon, a leader of the Coalition to Abolish STRESS and the Socialist Workers Party candidate for mayor, insisted that the Black people in Detroit were united in the knowledge that the only way to "stop police oppression . . . is the ability and willingness of the Black community to organize politically." Picketers carried signs reading "Stop the Racists--Enjoy Safe Streets," "Impeach Nichols," "Dope Pushers Equal Detroit Police," "Free Hayward Brown," and more. On April 28, a group organized by the Coalition to Abolish STRESS marched from Wayne State to Kennedy Square for another anti-STRESS rally, with huge numbers of DPD officers lining the route for 'crowd control.' Speakers denounced the DPD as a racist terror organization and argued that the main task of the movement was to "elevate the political consciousness of the community."

The anti-STRESS protests organized by radicals during the spring of 1973 drew a much smaller number of participants than previous mass demonstrations after the fatal shooting of Buck and Mitchell and after the Rochester Street Massacre. Radical groups believed that mass mobilization in the streets was an essential component of political transformation, but it was clear that most African American residents of Detroit were placing their hopes for transformation of the DPD in the ongoing mayoral contest and the opportunity to elect a Black mayor for the first time in the city's history. This was also the primary agenda of the mainstream civil rights groups and elected officials who had formed United Black Coalition in January 1973 with the goal of abolishing STRESS and reforming the police department through mobilizing the African American community to participate in the electoral process, which they believed would lead to Black control of the city government and DPD. While all factions in the anti-STRESS movement rallied behind Coleman Young, there was definite tension between the radical vision of local community control of the police department and the expectation of elite-led reform by the civil rights establishment.

The Mayoral Election: Young vs. Nichols. The DPD and its STRESS operation were effectively on the ballot in the 1973 mayoral election. The foremost champion of STRESS, Police Commissioner John Nichols, emerged from the primary as the perceived frontrunner with a strategy of mobilizing white voters behind the DPD's ongoing "crime" crackdown in Black neighborhoods and the downtown business district. Coleman Young denounced the "blackjack rule of the Detroit Police Department" and argued that "the police run the city." He associated Commissioner Nichols with the rampant police narcotics corruption revealed by the Pingree Street Conspiracy, stating that top DPD leaders were "either incompetent, incredibly naive, or actually implicated." He appealed to the Black electorate that "Detroit is a racially polarized city, and now is the time we need to have a Black mayor." Young also promised to fire the top white commanders in the DPD, to hire 1,000 Black police officers, to reduce the influence of the "racist" DPOA union, to abolish the Intelligence Bureau (which conducted mass illegal surveillance of political activists), and to establish a civilian review board that would guarantee independent investigations rather than whitewashes of civilian allegations of police brutality and misconduct.

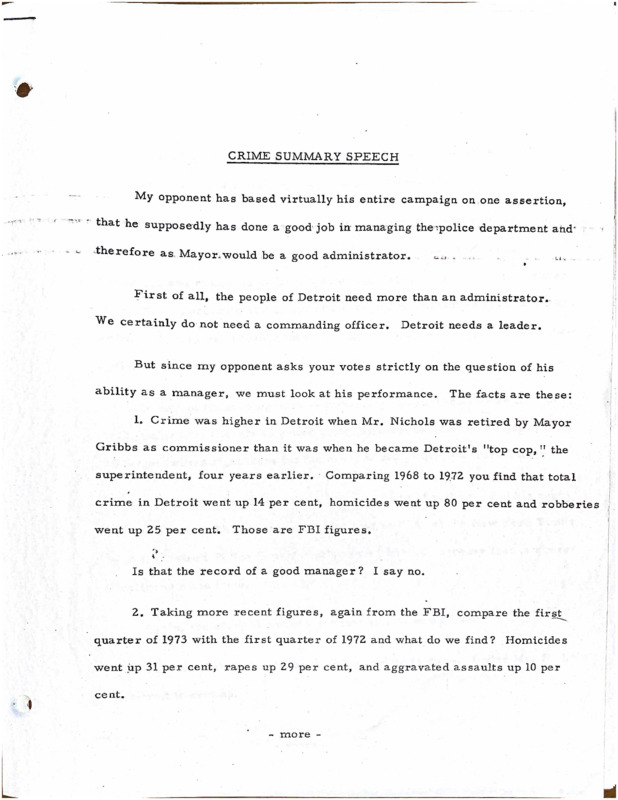

"Law and Order, with Justice." Coleman Young was a progressive, not a radical. He campaigned on the slogan of "law and order, with justice," and pledged to wage a more effective, non-racist, but certainly "tough" war on crime. In his standard crime campaign speech (gallery below, second from left), Young emphasized that violent crime had increased dramatically during the Gribbs-Nichols administration and insisted that his crime war would be tougher, smarter, and fairer. Young's campaign speech offered these promises and proposed these policies:

- "I will bring law and order, with justice, to the city of Detroit through more effective use of police manpower . . . and enforcement efforts on the most vicious and violent crimes"

- "Safe streets are a necessity. No criminal or thug, Black or White, can expect special favors from me"

- "Increase substantially the number of officers on the street"

- "More undercover investigations aimed at major drug traffickers"

- "Full scale investigations to be made of the numerous rumors of police corruption with drugs"

- "Training . . . for officers at all levels in matters relating to professionalism and community relations"

- "Improve recruitment programs to bring in larger percentages of minority police" and "having a force that more nearly reflects the racial composition of the citizens it serves"

- "Mini police" substantions established in neighborhoods and "more police will walk the beats"

- "New citizens complaint procedures will involve civilian investigation"

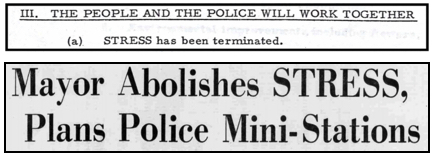

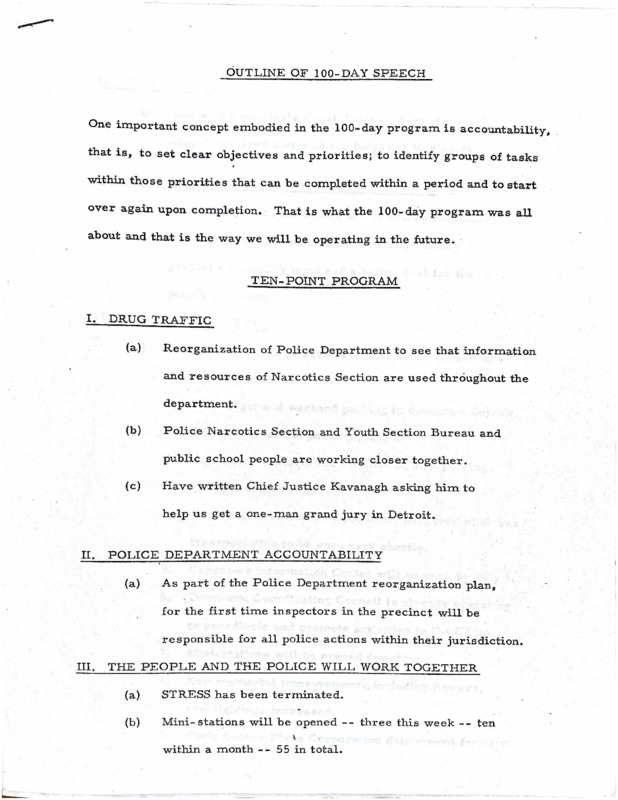

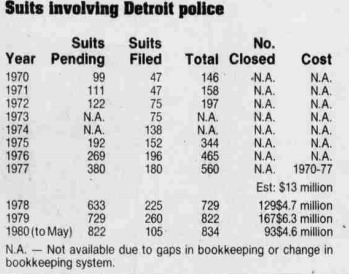

STRESS Abolished and Young's "All-Out War on Crime." Coleman Young narrowly won the mayoral election and then, in his inaugural address, promised both a "people-oriented police department" and a tough campaign to "drive the criminals from our streets." He warned "dope pushers, rip-off artists, and muggers . . . to leave Detroit" and even equated corrupt police officers with street criminals, saying "I don't give a damn whether they wear super-fly suits or blue uniforms with silver badges--hit the road!" Six weeks later, Mayor Young released a comprehensive plan for reform of the Detroit Police Department, with the highlight being the immediate abolition of STRESS. The Young administration's agenda also planned to create 50 new police mini-stations where uniformed officers would be embedded in local communities and set the target of a 50 percent Black police force by 1978. The new mayor further denounced the "extremely racist attitudes" of many white DPD officers and said that those who refused to change should "move aside" and resign. And finally, Mayor Young's order abolishing STRESS simultaneously committed the city government and Detroit Police Department to an "all-out war on crime."

The gallery below contains documents from the 1973 mayoral election, Coleman Young's crime control agenda, and the multimillion dollar payouts that the city of Detroit made in response to civil lawsuits against the DPD for wrongful death, excessive force, and other acts of police brutality both during and after the STRESS era.

Coda

The election of Coleman Young and abolition of STRESS marked the end of an era in the history of Detroit, marked by a white-controlled police department that committed routine violence and systematic abuses of the constitutional rights of Black citizens for decades and then escalated its campaign of racial criminalization in response to civil rights and black power activism. The Detroit Police Department killed more citizens per capita than any other city in the United States between the 1967 Uprising and the abolition of STRESS at the end of 1973, and the Black citizens of Detroit responded with one of the largest mass movements against police violence and brutality in the history of the United States. That tradition of Black community activism, and not just the documentation of police violence and brutality, is a central research finding of this Detroit Under Fire exhibit.

The Detroit Police Department never again embarked on a wave of racial violence as deadly as that of the late 1960s and early 1970s, but the takeover of the city government and its law enforcement apparatus by Black elected officials also did not fundamentally transform the patterns of police brutality and racial criminalization as much as Coleman Young's supporters had hoped. During his twenty-year tenure, Mayor Young expanded DPD wars on street crime, drugs, and gangs that overwhelmingly targeted young African American males and criminalized poor Black neighborhoods. These punitive policies escalated in Detroit and other cities nationwide alongside a massive ramping up of federal crime and drug control programs. The Young administration's affirmative action policies increased the racial diversity of the police department, but more Black officers did not lead to a steep reduction in brutality and misconduct incidents, and the DPD's tradition of whitewashing internal investigations into civilian allegations continued. Before election as mayor, Coleman Young had supported the establishment of an independent civilian review board to investigate and discipline police misconduct and criminality, a central goal of Detroit's civil rights movement since the late 1950s. Instead of an elected civilian review board representing local communities, the city of Detroit established a Board of Police Commissioner appointed by the mayor, which lacked adequate disciplinary authority and proved unable to overcome the "Blue Curtain" tradition of covering up brutality and misconduct and thwarting accountability for police crimes. The struggle over police violence and racial criminalization in Detroit continued under Mayor Young and will be the focus of our project's follow-up exhibit, Crackdown: Policing Detroit through the War on Crime, Drugs, and Youth, covering the 1974-1993 period.

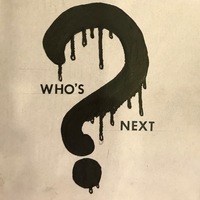

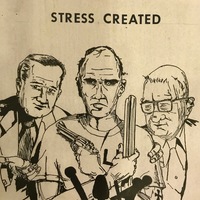

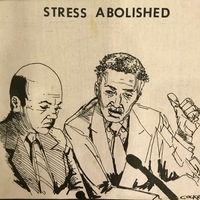

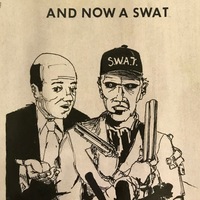

Radical anti-STRESS activists created the sequence in the gallery below, ending with the "who's next?" panel at right, both to condemn the murderous STRESS operation and to critique its replacements in Mayor Coleman Young's "all-out war on crime."

Sources:

Coleman A. Young Papers, Part II, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Kenneth V. and Sheila M. Cockrel Collection, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archive of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Detroit News Photograph Collection, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Michigan Chronicle, March 3, 17, April 14, May 12, 1973

Detroit Free Press, May 12, June 1, 1973, Jan. 3, Feb. 14, 1974, Aug. 3, 1980

Detroit News, May 28, June 25, 1973, Feb. 14, 1974

Groundwork, Sept. 1973

Heather Ann Thompson, Whose Detroit? Labor, and Race in a Modern American City (2001)

Michael Stauch, Jr., "Wildcat of the Streets: Race, Class and the Punitive Turn in 1970s Detroit," (Ph.D. diss., Duke University, 2015)

Elizabeth Hinton, From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime (2016)