War on Poverty → War on Crime

TAP: Detroit's Local War on Poverty

The Jerome Cavanagh administration launched the Total Action Against Poverty (TAP) in 1964, preceding federal intervention into the city’s poverty eradication efforts. While TAP started in Detroit, the program quickly expanded in 1965 with the passage of federal programs in the War on Poverty. Within months of its inception, TAP received over $3.4 million in federal grants. Federal funding was directed primarily toward in-school programs and the creation of various anti-poverty centers.

TAP was a catch-all antipoverty initiative, taking over the roles of previous antipoverty organizations such as the Mayor’s Community Action for Detroit Youth Committee (CADY). In July 1964, TAP laid out the foundational goals of Detroit's local war on poverty in this letter addressed to the Common Council of Detroit (right). The letter details four specific categories of proposals: health and food, education and training, community organization and self-help, and structural changes (such as increased minimum wage).

TAP accepted responsibility for promoting programs that fell into the larger national War on Poverty. To that end, the group noted that it was vital for policies to focus on the “complex economic, social, and educational conditions that breed poverty.” This philosophy suggests that the causes of poverty lie in the behavior and lifestyle of the individual, but also that changes to the environment could affect the situation of poor people as well.

Connecting the War on Poverty to the War on Crime

Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty began with an emphasis on the improvement of social conditions such as education, housing, and government assistance. However, the federal War on Poverty became part of the War on Crime through the broadening of federal influences, a greater presence of law enforcement on the streets, and bringing the social and economic conditions of the urban poor into the local spotlight.

The Johnson administration viewed eradicating poverty as a means of controlling rising crime rates. In his “Special Message to the Congress on Law Enforcement and the Administration of Justice,” Johnson explained that the purpose of fighting poverty is to “eliminate the causes of criminal activity whether they lie in the environment around us or deep in the nature of individual men.” Eradicating poverty, therefore, was a crime-reduction strategy as well as a genuine social welfare cause, and so the War on Poverty became closely connected to the War on Crime.

The War on Poverty enabled the national government to intervene extensively in state and local affairs. For example, by creating national youth organizations, the federal government cemented itself into the lives and futures of American cities. Following this trend, the War on Crime extended the expansion of federal powers the War on Poverty had already stretched. In his special message, Johnson went on to discuss the Law Enforcement Assistance Act (LEAA) of 1965, which gave the federal government, particularly the executive branch, more influence over the operations of local law enforcement. Through the LEAA, federal funding to local departments was contingent on meeting national quotas and requirements.

In this same 1965 address, Johnson discussed the role of the citizen in his War on Crime. The President claimed that a lack of respect for law enforcement was a civilian-oriented problem, not a problem started by police. American citizens, according to Johnson, were responsible for respecting the police, reporting criminal behavior, and should “cooperate with law enforcement in any other way.” In the process of federalizing local law enforcement, Johnson bestowed upon the individual officer tremendous power and discretion when dealing with citizens.

While Johnson spoke of increased federal funding to local law enforcement, enhanced police technologies, and other punitive measures of crime control, he envisioned a different long-term solution. In the short term, Johnson's aim was to eradicate crime with the swift hand of justice; however, he also stated that "the long-run solution to the view of crime is jobs, education, and hope." These War on Poverty sentiments were at the backbone of Johnson's War on Crime, exposing the truly hypocritical nature of a liberal War on Crime. On the surface, Johnson's war appeared to be fighting for occupational and educational opportunities, but a deeper look reveals that his means of achieving such goals also depended on punitive police action because "crime will not wait while we pull it up by the roots. We must arrest and reverse the trend toward lawlessness."

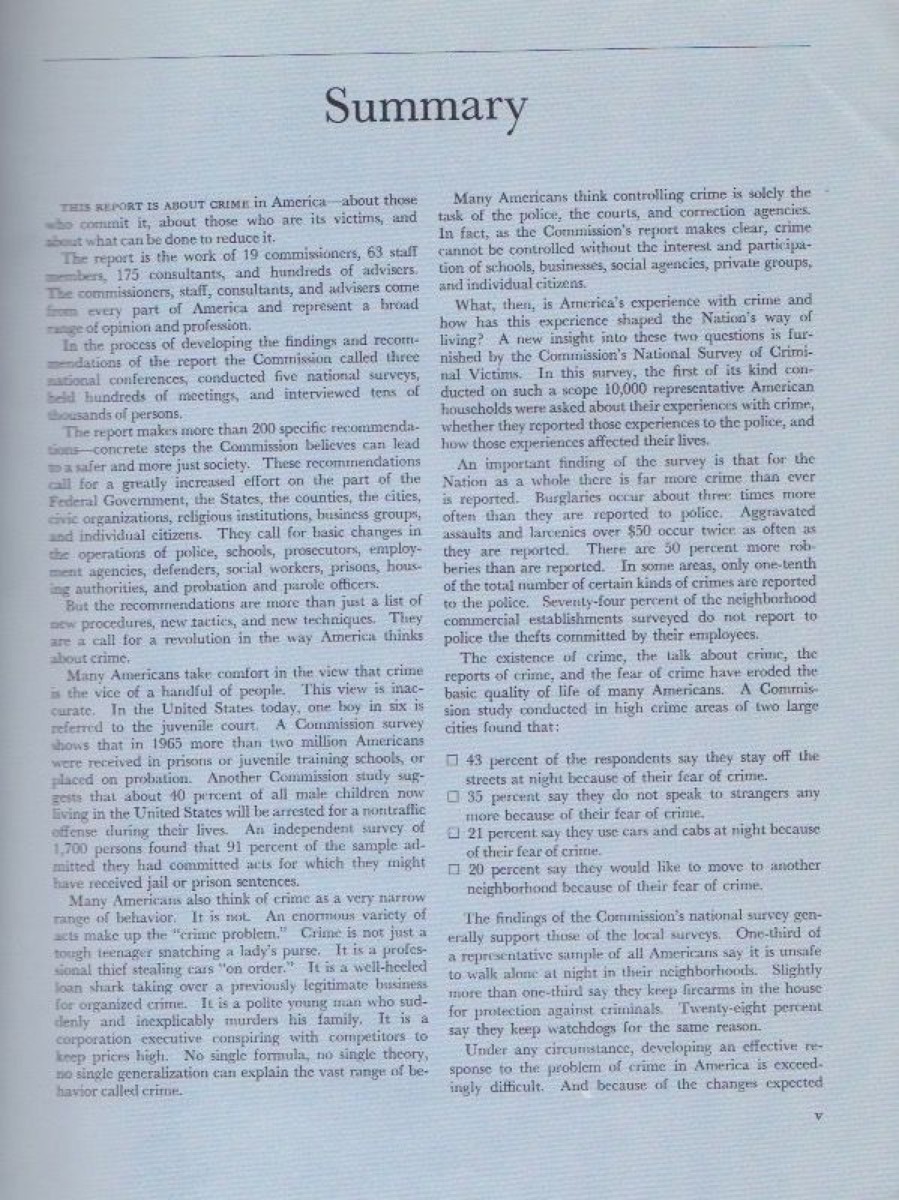

The President’s Commission on Law Enforcement and the Administration of Justice (CLEAJ)

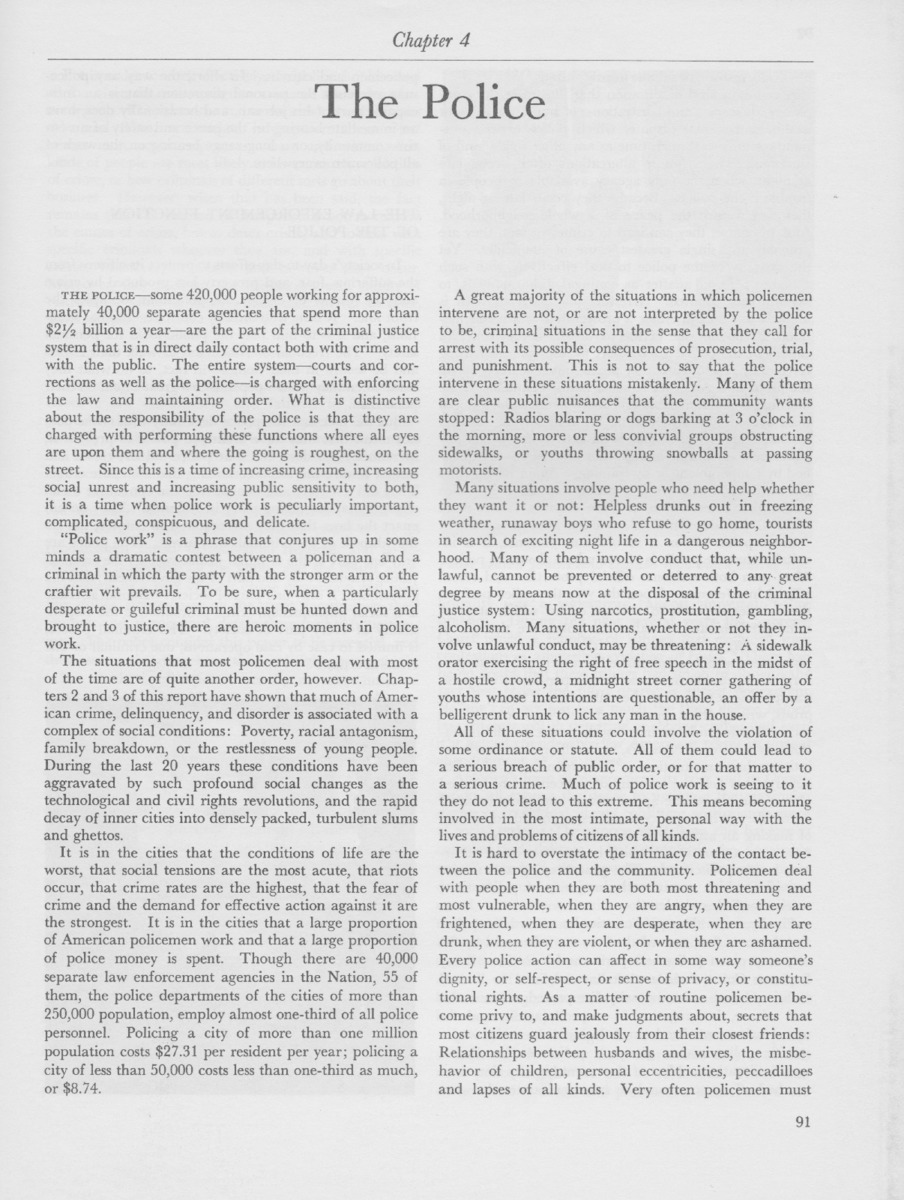

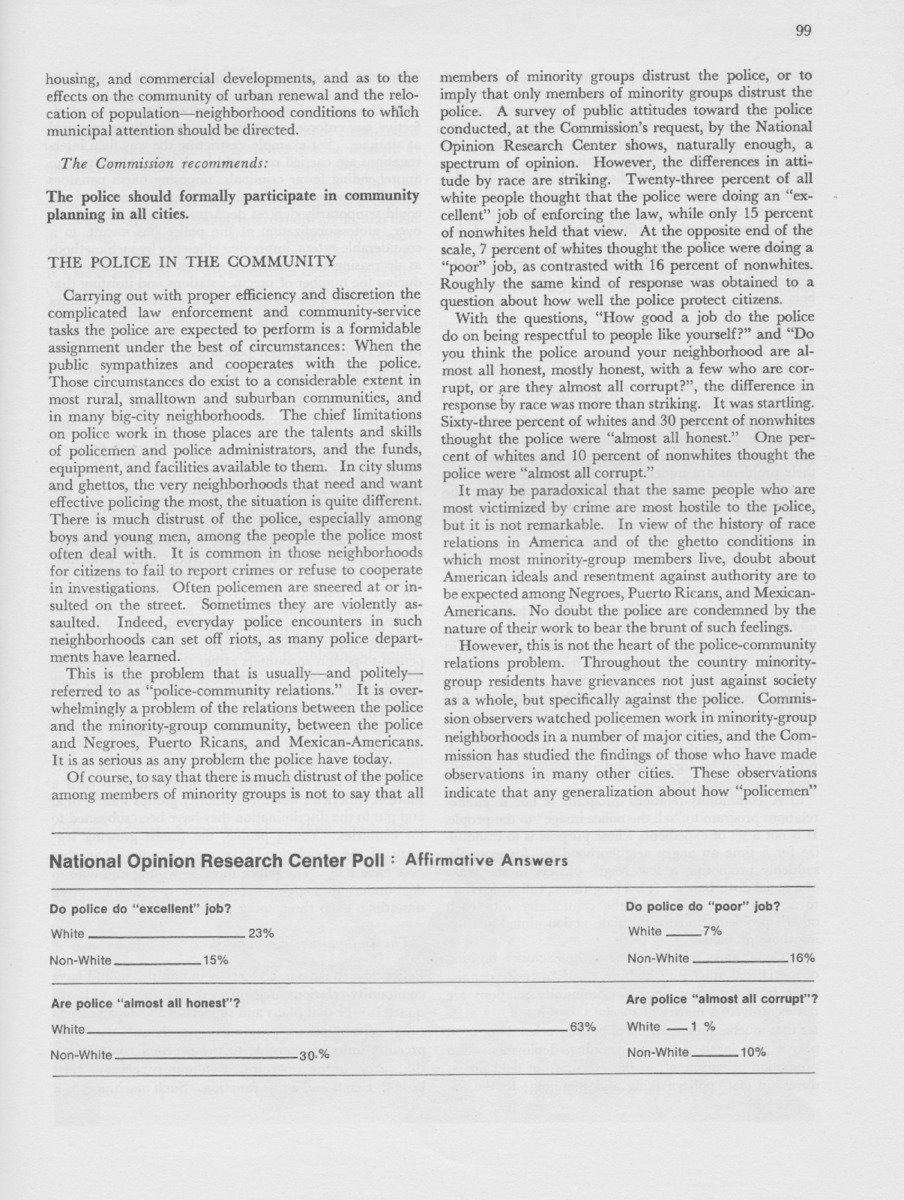

President Johnson appointed a special Commission on Law Enforcement and the Administration of Justice (CLEAJ) to develop the philosophy of the national War on Crime. In its report, the CLEAJ found that a majority of police work was not related to criminal incidents but instead involved discretionary enforcement of social order. Police officers spend most of their time monitoring "poverty, racial antagonism, family breakdown, or the restlessness of young people." Police officers, as this report explains and defends, were equally tasked with enforcing the law and maintaining social order through individual discretion. In particular, Johnson's commission cited vice and disorder in poor neighborhoods as justification for increased police attention. This vision proved to be the foundation of the massive ramping up of discretionary police enforcement in urban black neighborhoods during the mid-1960s, including in Detroit.

Click on the documents in the gallery below to explore various aspects of the Commission on Law Enforcement and Administration of Justice's report, The Challenge of Crime in a Free Society.

Youth Programs and Police Involvement

Youth programs were a central feature of President Johnson's and Mayor Cavanagh’s war on poverty. These programs, offered to youth of low-income or at-risk backgrounds, sought to simultaneously prevent juvenile delinquency and teach children about citizen responsibility. Additionally, these programs afforded Detroit youth the time and space to have fun together.

While theoretically sound in their conception, youth poverty programs became yet another instrument of the War on Crime. For example, the Community Action for Detroit Youth Committee (CADY) was responsible for social programming for youth in impoverished areas but also involved itself in the fight against crime in Detroit before merging with TAP. CADY employed government funding and money contributed by local businesses to launch an attack on juvenile delinquency, targeting poor black neighborhoods. By supplying inner-city youth with responsible outlets for free time, socializing, and community-based learning, CADY attempted to diminish incidents of youth-related criminal behavior in Detroit. CADY’s crime control efforts were aided by President Johnson’s Committee on Juvenile Delinquency and Youth Crime.

Additionally, the city of Detroit handed control over a group called the Youth Service Corps to the Detroit Police Department. By making the DPD an essential actor in efforts to eradicate poverty, the city of Detroit successfully merged the wars on poverty and crime. While this seemed like a good idea to improve police-community relations, it also increased criminalization by involving police in the social welfare activities of poor urban youth.

At a banquet for the Detroit Youth Service Corps, Police Commissioner Ray Girardin gave a speech (right) outlining the contributions of the group to the DPD. Members of the Youth Service Corps, according to Girardin, added thousands of hours of police activity to the department, reported on traffic violations, and aided officers dealing with civil infractions. Instead of offering children a summer of team-building and fun activities, the Youth Service Corps and the DPD weaponized some of Detroit’s youth. To prevent juvenile delinquency, the police turned at-risk teens into their crime-searching scouts.

Citizens in the War on Crime

The phrase “War on Crime” suggests that the government was the sole actor. However, the development of the War on Crime would have been impossible without citizen approval and citizen participation. City leaders and law enforcement officials encouraged Detroiters to partake in their pursuit to reduce crime rates by suggesting many ways to become involved.

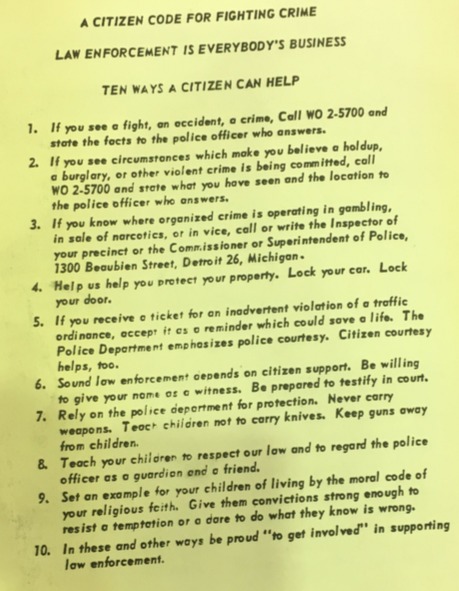

A pamphlet produced by the Police and Religious Leaders Conference on Crime offers ten suggestions for ways in which citizens can involve themselves in the War on Crime. These actions range from notifying police of burglaries to locking one’s doors, from respecting officers to teaching children to follow the law. While the list offers legitimate ways to fight crime, the underlying message is to distrust fellow citizens by stressing surveillance of neighbors in order to maintain the rule of law.

Many members of the general public supported the Detroit Police Department and wanted a tougher War on Crime. While civil rights groups called for police reform, a substantial portion of Detroit's citizenry stood by the men in blue. White residents, in particular, refused to recognize police brutality as a significant public concern and called for increased police presence in impoverished black neighborhoods (also see the citizen letters on the Stop and Frisk page).

Substantial segmenets of the African American community also supported more policing through the War on Crime. Many African-American citizens called on the police to address the crime issue in their communities. Because of a legacy of police neglect and corruption in vice markets, as well as concentrated poverty and racial segregation, poor black neighborhoods suffered from the highest crime rates. Many black residents wanted effective crime control without police brutality and racial injustice, which Mayor Cavanagh had frequently promised. They wanted the DPD to uphold its duty to "protect and serve" the community and reduce crime rates. Yet instead of protection, black neighborhoods more often were met with police violence, and instead of serving the community police too often allowed crime to persist.

Sources:

Detroit Free Press, June 12, 1964

Mel Ravitz Collection, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

President’s Commission on Law Enforcement and Administration of Justice, The Challenge of Crime in a Free Society (Washington: GPO, 1967)

Ray Girardin Papers, Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library

Detroit Commissions on Community Relations (DCCR)/Human Rights Department, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Elizabeth Hinton, From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime (Harvard, 2016)