Affirmative Action

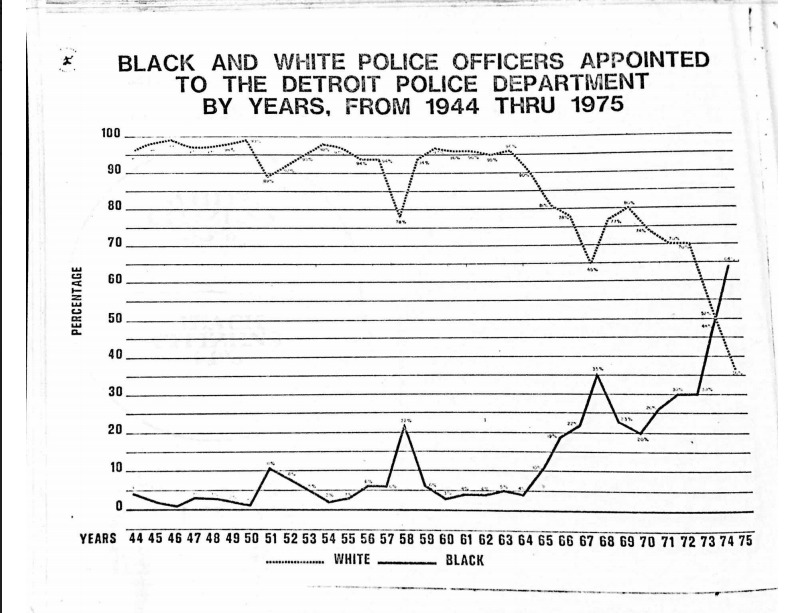

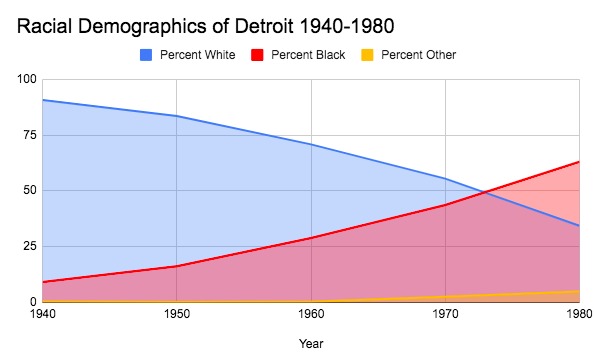

For the majority of the 20th century the Detroit Police Department consisted almost entirely of white men. Although the first black officer joined the force in 1893, African American police officers remained in the extreme minority prior to the election of Coleman Young. During the first half of the century, the police department was more or less reflective of the population of the city as a whole. In the years following World War 2 and the ensuing Great Migration the demographics of the police department failed to keep up with the increasingly diverse population. By 1963, African Americans made up over 25% of the city but only 3% of the police force.

The lack of African American representation in the DPD was hardly a mistake. Prior to 1967 outright discrimination and segregation had substantial limits on the ability of Black Detroiters to join the DPD and to recieve promotions. Because the department was more than 90% white for almost the entirety of the 1950s and 60s, racial biases easily inserted themselves into hiring, assignment, and promotion practices. Those biases often formed the basis for unwritten rules that hampered any natural progress in the DPD’s composition that may have occurred as the city’s population diversified during the 50s and 60s. For example, testimony from several high ups within the DPD, given in response to a 1974 lawsuit, demonstrated that prior to the 1960s the assignment of officers to everything from scout cars to precincts involved strict segregation between white and black officers. That same testimony also revealed that: “Black police officers were not placed in positions where they would regularly control white prisoners” and “it was the custom neither to assign blacks to public positions of authority...nor to place blacks in positions supervising whites.” These informal policies of discrimination, as well as everyday discrimination from white officers, “stigmatized black officers” and “limited the available training, experience, and promotional opportunities” according to an appeal in the same 1974 lawsuit. The end result of the deeply entrenched racial discrimination that defined many of the DPD’s practices was twofold. Not only did the DPD suffer from a lack of African American police officers, those who were on the force were overwhelmingly relegated to the lowest level positions and assignments.

As the city of Detroit became increasingly more African American the lack of representation in the police force became a greater and greater problem. Black citizens had previously been subjected to violence at the hands of the police but many residents increasingly had the feeling that the police were there more to repress them than to protect them. These tensions boiled over in 1967 when African-American reactions against a police raid of a blind pig escalated into a full blown uprising. During the five days of the disturbance the city called in both state police and the national guard in an attempt to quell the disorder. In the months after the 67’ uprising, black Detroiters recommitted themselves to the goal of better integrating the police force.

Black residents were not the only ones dissafected by the majority white police force. African American police officers expierienced extreme prejuidice and discrimination from their white counterparts. The lack of African American representation among higher-ups in the department virtually eliminated the possibility of getting any recourse for these types of experiences.

David Bruce is a former police officer who joined the Detroit Police Department in 1966. As an African American, Bruce was among the first waves of black officers that began to integrate the force in Detroit. In this interview, part of an oral history project about the 1967 Detroit uprising created by the Detroit Historical Museum, Bruce recounts some of the problems he had to deal with as a black officer in a majority white police force. Bruce also describes some of the changes he noticed in the force's compisition after the uprising. Bruce's interview provides unique insight into the experiences of black officers prior to the affirmative action efforts that the city would underake later on. Racial descrimination from fellow officers was somewhat a fact of life for African American's in the DPD at the time. Moreover, black officers had no ability to complain to higher up's about the blatant racism they faced because there were even fewer black lutenents and seargents. Bruce also comments on the impact that the 67' uprising had on spurring action within the black community and the police department in favor of a more representative DPD.

In 1973, Black Detroiters crys for police reform and integration won a major victory through the election of Coleman Young. Young was the first African American Mayor in Detroit's history and he ran on a platform largely centered around police reform. After his election, Coleman Young made immediate efforts to help bring more African-Americans into the police force. he did so largely through an affirmative action program which sought to hire and promote more black officers within the DPD. Additionally Young tried to bring in and promote a greater number of female officers. Over the course of his administration Young's police department continued to use affirmative action policies to help improve the representation of African Americans and women within the DPD. White male officers and the largely white police union faught against these policies through lawsuits and protests. Some officers even turned to acts of racial violence in their efforts to resist the full integration of the department. Despite those setbacks, by 1993 the DPD managed to achieve a even split between white and black officers, finally succeding in creating a police force that was more or less represntative of Detroit's racial demographics.

Sources:

Coleman A. Young Mayoral Papers, Burton Historical

Collection, Detroit Public Library.

U.S. Census Bureau, Census.gov, Using American FactFinder, (April 15, 2020).

Detroit Police Department, Anual Report, Serial. (DPD, 1970-1981), Hatcher Graduate Library, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI.

Interview of David Bruce by William Winkel, October 19, 2016, Detroit Historical Society, Detroit, MI.