DPD Racism in Hiring/Promotion

A Segregated Police Department

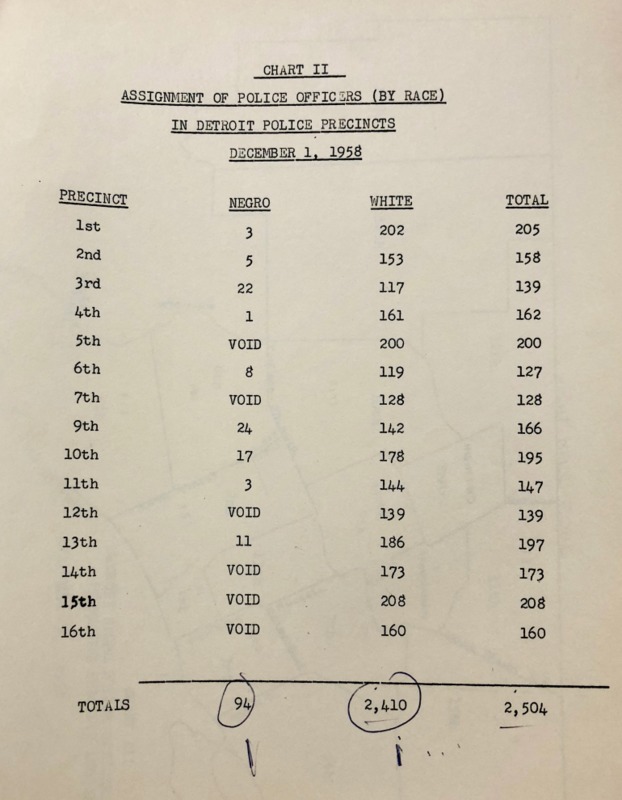

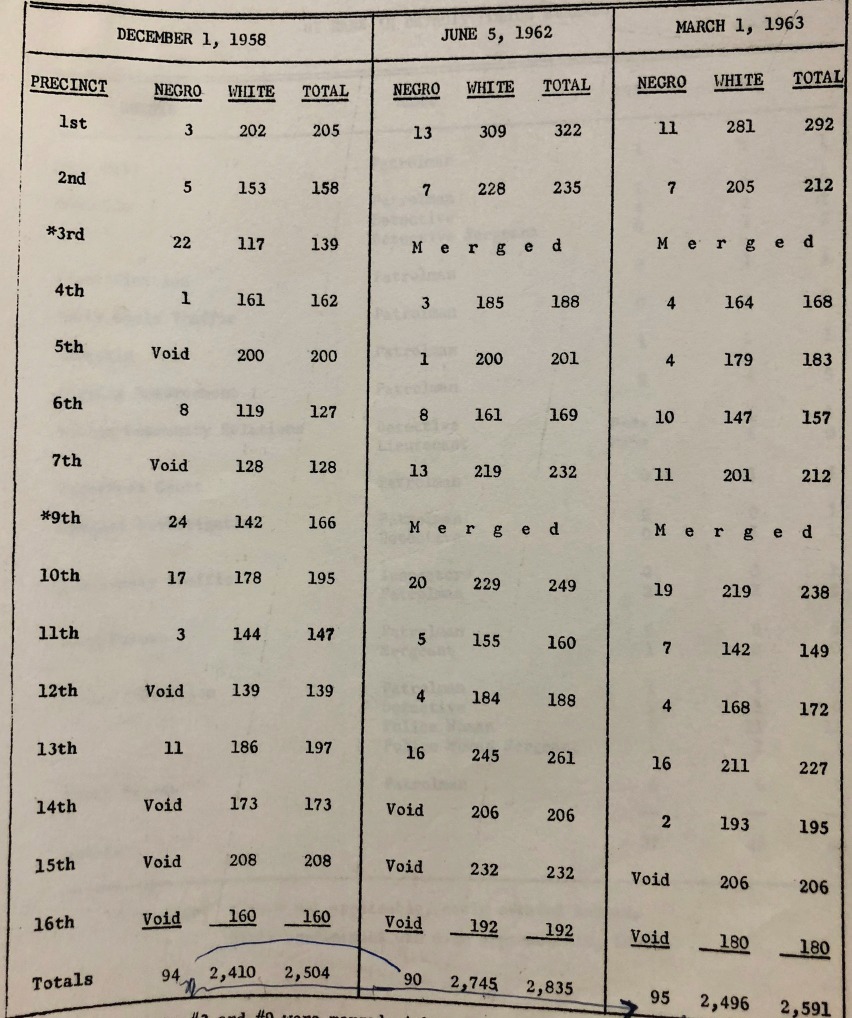

During the 1950s, Detroit Police Department was an overwhelmingly white institution in a Jim Crow northern city. By the end of the decade, African Americans made up almost one-third of the total population in the city of Detroit. Black officers represented less than 4 percent of the DPD force: 94 officers out of 2,504 total in 1958, 95 out of 2,591 total in 1963. Almost all DPD officers, and all street patrolmen, were men.

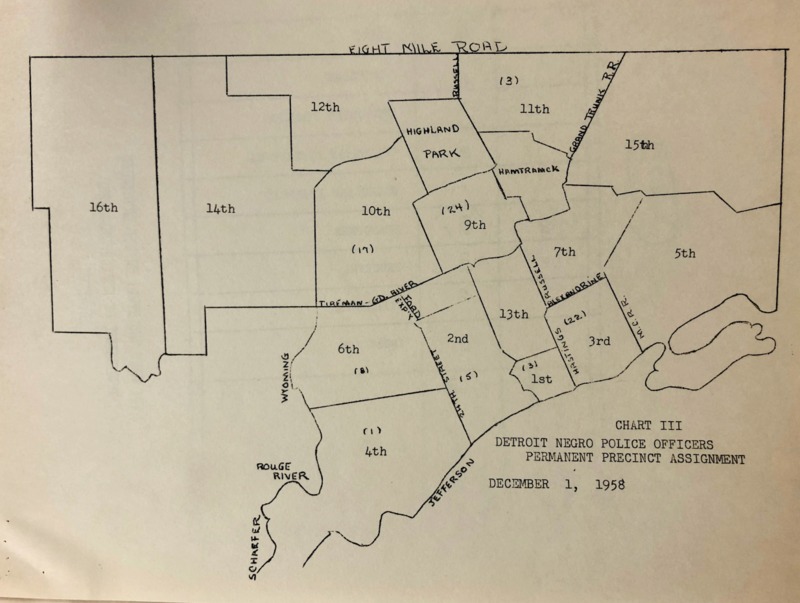

Civil rights groups, led by the Detroit Urban League (DUL), pressured the police department and city government to hire and promote more African American officers and make the DPD more representative of the city it served. In a 1958 report, the DUL provided these maps and charts (below) documenting the very small number of black officers on the force. Additionally, almost all black officers were patrolmen, the lowest rank and lowest pay. There were only four African American sergeants and zero detectives, inspectors, or lieutenants. There were, not surprising, no African Americans in the upper-level leadership of the DPD either.

The DPD refused to provide the Urban League with information on how many black applicants were not hired and also declined to explain why six precincts had no black officers at all. The DUL also highlighted the "unofficial policy but official practice of segregating officers of color in scout cars, on walking beats, and in partner assignments" (the DPD announced a new policy of non-segregation in precinct assignments in March 1959, but implementation was halting). The DUL called on city leaders to require the DPD to practice equal opportunity and concluded:

Map of Racial Breakdown of Police Officers by Precinct, 1958, and Location in Racial Geography

The map below reproduces the number of white and black officers in each precinct along with the geographic location of the precinct station house in the city's segregated neighhorhoods (green = white population; blue = black population). Hover over each station icon to view the racial breakdown of officers. Note that many of the precincts in the all-white neighborhoods had zero African American officers.

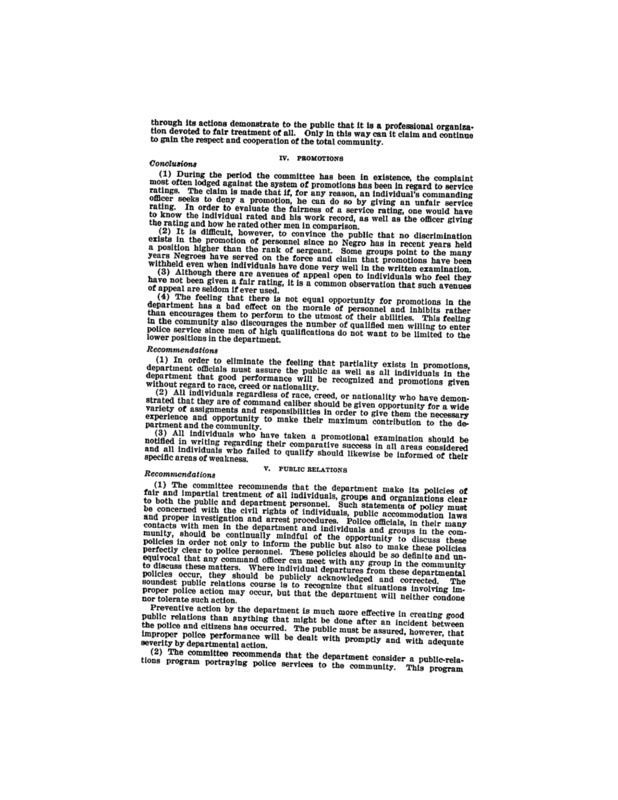

Citizens' Advisory Committee on Police Procedures

In 1958, Mayor Louis Miriani appointed a Citizens' Advisory Committee on Police Procedures to improve community relations between the DPD and African Americans in Detroit. The committee consulted with the Detroit Urban League, the NAACP, the ACLU, the Michigan Chronicle, and the Cotillion Club (a group of black civic and business leaders who sought better police-community relations). The main focus of the committee was the lack of racial diversity in the DPD.

The Citizens' Advisory Committee report, released in January 1960, made the following recommendations:

- The DPD should expand its recruitment efforts to actively seek applications from "qualified men" from a wider variety of backgrounds to reflect the goals of equal opportunity

- The DPD should make its policies of accepting or rejecting applicants more transparent and fair

- The DPD should assess applicants for their "willingness to work with people of various ethnic, religious, economic, racial and social backgrounds"

- The DPD should train new officers in human relations in order to reduce police-community tensions

- The DPD should provide material to new officers that clarified the constitutional rights of all citizens

- The DPD should hire, assign, and promote officers "without regard to race or creed"

The Citizens' Advisory Committee emphasized that fair employment in the police department would lead to more effective law enforcement by increasing community respect (meaning: African American community respect) for the DPD. The report warned:

Read the full report at right and the recommendations in the gallery below.

Black Officers and Racial Discrimination

In December 1960, when the United States Commission on Civil Rights held hearings on racial discrimination in Detroit, two retired black police officers, Joynal Muthleb and Jessie Ray, testified to the pervasive mistreatment that they faced while on the force. They did not appear voluntarily, fearing retaliation from the DPD, but instead came under subpoena. The previous page on Exposing Police Brutality recounted Methlub's and Ray's descriptions of the excessive force and deprivation of constitutional rights against African American civilians that both witnessed.

Regarding his own experiences, Muthleb stated that the DPD did not want black officers to join the force, that the hiring and promotion processes were racially discriminatory, and that the DPD as clear policy would not place black officers in specialized bureaus and higher-paying, higher-ranking positions. He described a system where white supervisors almost always gave black officers low performance ratings, so it did not matter how well they did on the written exams, because they always lost out on the subjective parts of promotion. Muthleb concluded:

Jessie Ray described working on a segregated, "all-colored crew" for most of his time on the force. He also told of being beaten by a white officer who was involved in an illicit gambling operation that Ray discovered, which landed him in the hospital and which the DPD covered up. Then the department demoted him, and he eventually quit.

Read Joynal Muthleb's full testimony here. Read Jessie Ray's full testimony here.

DPD Hiring 1958-1963: No Civil Rights Progress

The DPD did almost nothing in response to the 1958 expose of racial discrimination by the Urban League and the 1960 report urging fair employment by the Citizens' Advisory Committee on Police Procedures. The police department did accounce a policy on paper that squad cars would be desegregated, and did slowly assign a few officers to some of the all-white precincts. But nothing changed in hiring and promotion practices. In December 1960, Police Commissioner Herbert Hart promised the U.S. Civil Rights Commission that the DPD did not discriminate on the basis of race in its hiring and promotion practices. The numbers tell a very different story.

In October 1963, the Detroit Urban League released a revised version of its "Report of the Employment Practices of the Detroit Police Department." The DUL report traced the progress, or lack thereof, in the hiring and assignments of African American police officers between 1958 and 1963. The total number of black officers had increased by one, from 94 to 95, during a half-decade of DPD promises of reform and equal opportunity. The ratio of black-to-white officers had actually decreased from 3.75% to 3.67% during this time period.

The maps below show the statistics on white and black officers in each precinct in 1958 compared to 1963. The main change is that only two precincts did not have African American patrolmen in 1963, whereas six were completely segregated in 1958. Otherwise, the maps show a story of the continuity of racial discrimination and inequality.

Map of Racial Breakdown of Police Officers by Precinct, 1958 and 1963, and Location in Racial Geography

Chart of Racial Breakdown of DPD Precincts from Detroit Urban League's 1963 Report

Sources:

Francis A. Kornegay Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

Hearings before the United States Commission on Civil Rights, Detroit, Michigan, December 14-15, 1960, Folder 001481-025-0244, Papers of the NAACP, Major Campaigns-Legal Department Files, National Archives