Police Mini Stations

Campaign to Fortify the Police and the People

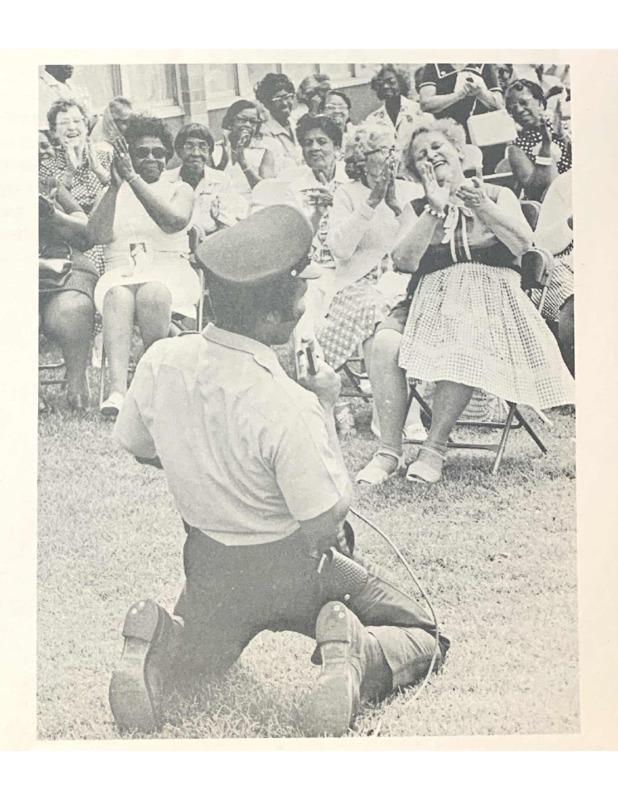

Point three of Mayor Young’s Ten Point Plan, only behind drug traffic and police accountability, was to ensure “the people and the police work together,” (1973). In Mayor Young’s campaign crime summary address, he proposes mini offices “staffed with small police squads - aided by civilian office workers… established in neighborhoods and commercial centers,” (Young, 1973). Thus, police mini-stations became the hallmark of Mayor Young’s initiative to build a positive relationship between the Detroit Police Department and the people.

Upon inauguration, in February of 1974, Mayor Young issued an executive order to Police Commissioner Tannian to reform the DPD, where he calls for the formal termination of the STRESS program and the relocation of officers to fifty new mini-stations around the city. Publically, Young continued to advertise that community involvement was central and necessary to the success of the mini-stations.

Connections to National Trend of Community Policing

Mayor Young’s police reforms were highly reflective of his “law and order, with justice” platform. Further, Mayor Young pressed for reforms that would simultaneously control crime and alleviate racial antipathy within the DPD. He argued that the solution was to fortify the relationship between the community and the police department. The majority of Young’s campaign vow that “The People and the Police Will Work Together” ultimately translated into community policing, an approach to law enforcement trending in cities nationwide. This approach is valued as a means of crime control and improve community perceptions of police. Thus, the establishment of small, satellite police stations, dubbed mini-stations, throughout Detroit between 1974-1977 became the Mayor’s primary innovation in community policing. On the surface, the intention of the mini-station program was to promote regular contact between police officers and community members. Internal correspondence indicates that this publicized intention, of community-relationship building, was not the primary driver for gaining advocacy. Rather, the primary goal of the mini station initiative was crime prevention and control—with community involvement being only a supplemental benefit.

Construction and Implementation of Mini Stations

Between 1974 and 1976, the DPD constructed and operated approximately 42 police mini-stations. The mini-stations, as advertised, were embedded into neighborhoods. They were deliberately placed amongst local establishments and as tactical mobile units, but more intimately, in the lobbies of public housing developments and community centers.

Housing discrimination was particularly threatening to Black lives in Detroit throughout the 20th century. The scarce public housing initiatives that emerged following liberal initiatives at the turn of the century were almost exclusively racially segregated. The Brewster-Douglass, Sojourner Truth, and Jefferies Projects were three of Detroit’s primarily Black public housing communities. At least three police mini-stations were deliberately constructed either inside or within one mile during the program’s first two years. Federal funds were allocated for the construction and operations of mini-stations in two of these locations—within the Brewster-Douglass and the Jefferies Projects. Thus, the construction of mini-stations within communities of people that experience the intersections of discrimination on two fronts, socio-economic status and race, is clear evidence of the deliberate criminalization of both poverty and Black lives, as suggested by Hinton in From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime. The police department advertised the mini-station program as an initiative to make citizens feel safe in their own communities. However, this degree of police omnipresence indisputably contributed to the arrest of thousands.

Public Housing & Mini Station Locations

Execution: Different Perceptions of Success

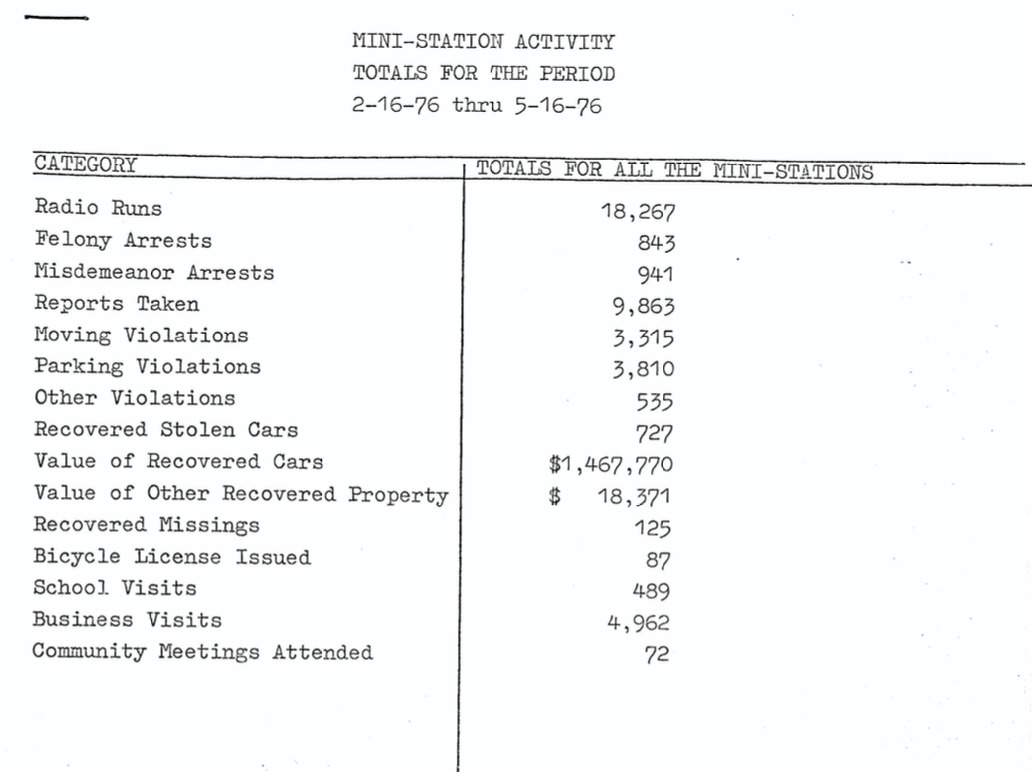

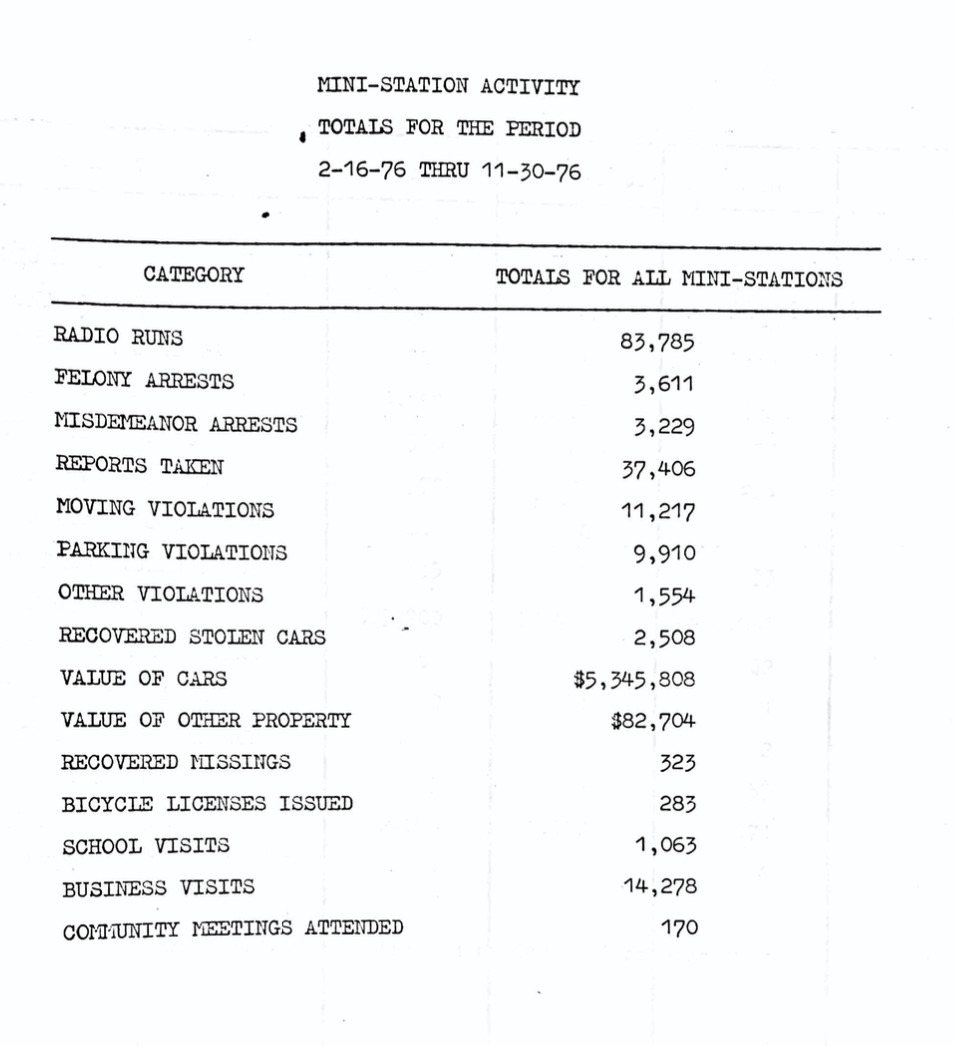

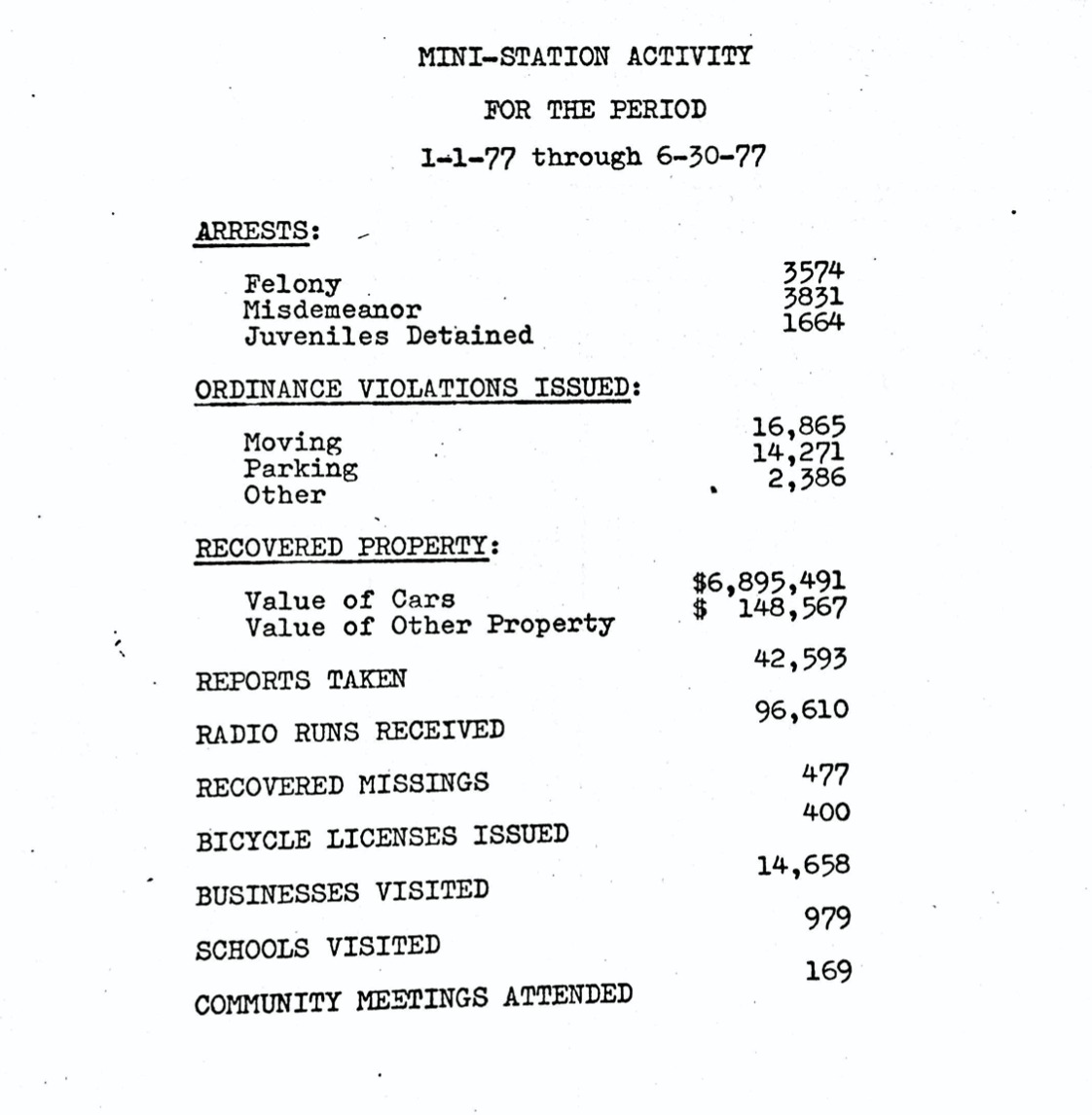

By putting more cops on the beat, the mini station program inevitably led to an increase in arrests. Consequently, it is then easy for law enforcement officials to interpret these rates exclusively in terms of initiative success--making any program that increases arrests appear to be controlling crime. This concept undoubtedly contributed to the success of James Bannon, commander of the Mini Station Administration Unit, in promoting the initiative. In a 1976 memo to Mayor Young, Bannon hyperbolizes these results, noting that “the data period prior… would be substantially zero.” The increasing arrest rates were also appealing from a federal standpoint, as much of the mini station funding was derived from LEAA grants. It is apparent since the initial 1973 LEAA grant proposals that federal interpretation of the initiative would be primarily for crime control--entirely excluding community engagement as a goal, but rather as an auxiliary benefit.

In a short time, it became clear to many law enforcement officials that the mini station program failed or did little to fulfill any efforts to promote community engagement. Mini station personnel were encouraged to carry out such activities while on duty, including visiting local businesses, schools, and community meetings. Quantitative reports of the mini station activities highlight the minuscule contributions made to the community aside from law enforcement. In 1976, the mini stations issued upwards of ~7,000 arrests, visited ~14,500 businesses, but visited ~1,100 schools and under ~200 community meetings. In 1977, the same activities have consistent reported numbers for the first six months and even become more specific regarding youth enforcement. The period highlights an upward trajectory in all categories for the first six months, but most significantly in arrests. These reports are indicative of the slim efforts made by mini station personnel to engage with the community--despite recommendations and efforts made from higher law enforcement officials.

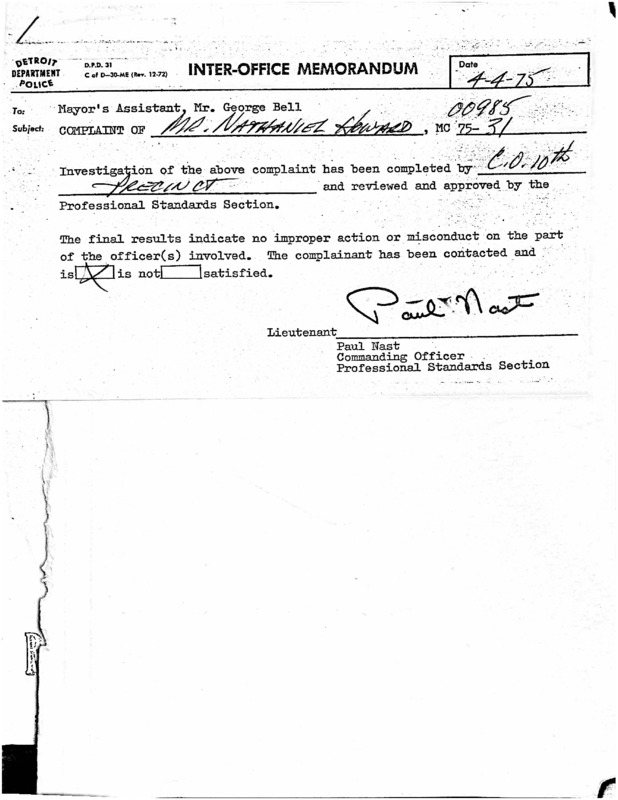

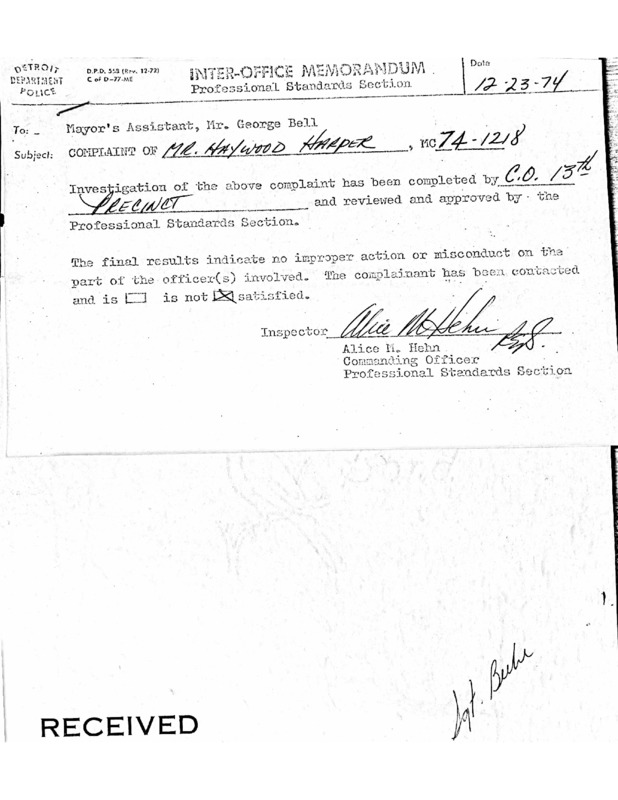

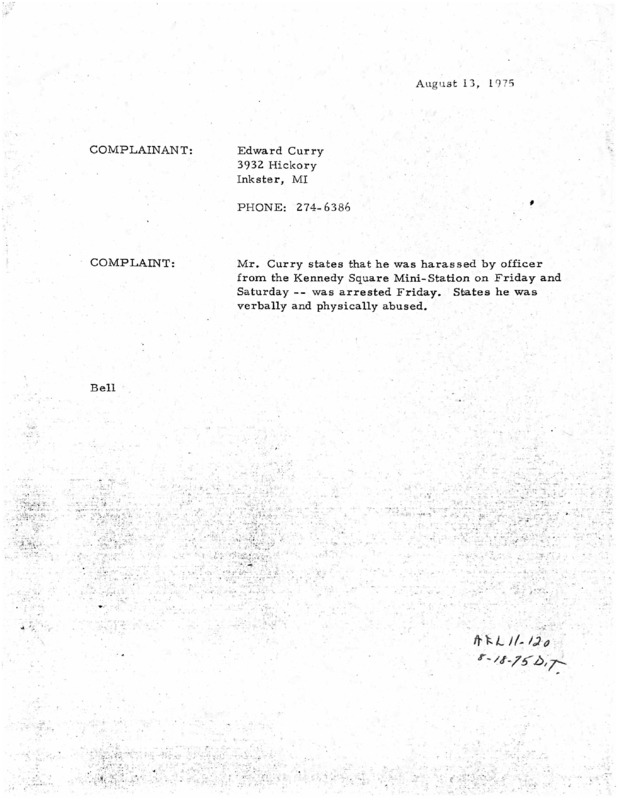

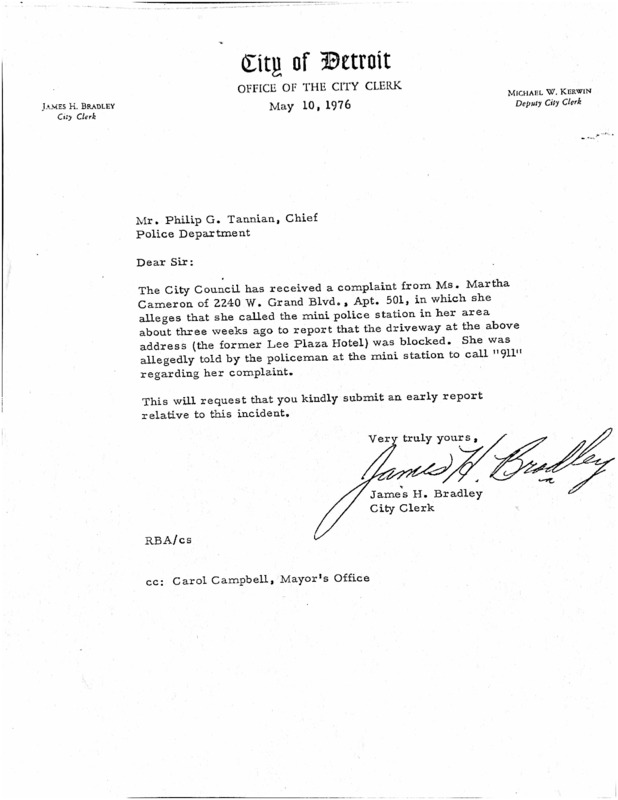

Civilian Complaints Involving Mini Station Officers, 1974-1977 (incomplete)

Sources for this page:

Coleman A. Young Collection, Walter Reuther Library, Wayne State University, Detroit, Mi.

Hinton, E. (2016). From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime. Harvard University Press.

Stauch Jr, Michael. "Wildcat of the Streets: Race, Class and the Punitive Turn in 1970s Detroit." PhD diss., Duke University, 2015.