1. Police-Community Relations

The Detroit Police Department and its many critics told radically different stories about the state of police-community relations during the early 1970s. The following two examples from the Detroit Commission on Community Relations and the Michigan Chronicle represent mainstream civil rights critiques of the DPD during the STRESS era; the charges leveled by black power and other leftist organizations, as documented later in this section, were far more radical. Black power groups considered the reform project of "police-community relations" to be a liberal facade and argued that the DPD's mission was fundamentally racist and designed to defend white power and maintain social control of the black community through violence.

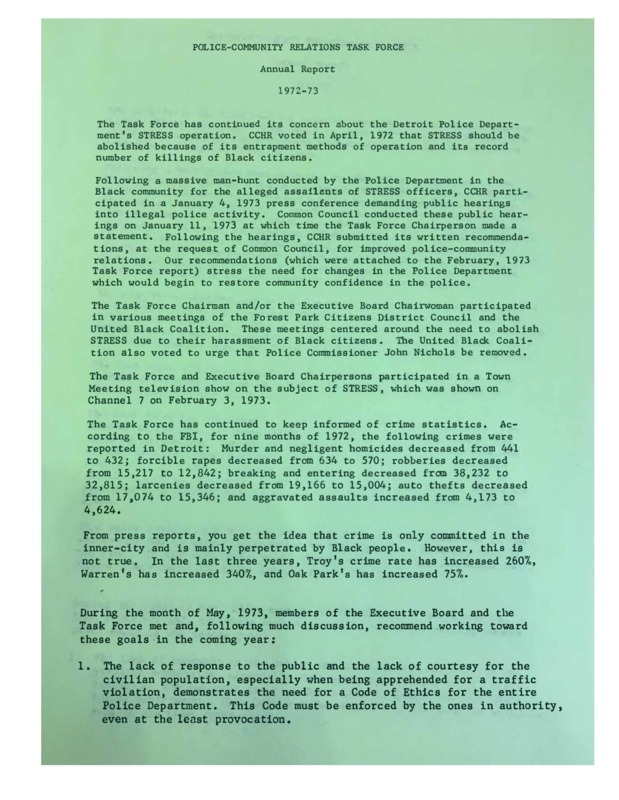

The Detroit Commission on Community Relations (DCCR), the investigative agency of the city government dedicated to civil rights enforcement, bleakly declared the mutual hatred and racial tensions between the Detroit Police Department and the African American community to be at an "all time high" by 1973. In its annual report, the DCCR's Police-Community Relations Task Force emphasized the urgent need to reform the DPD in order to "begin to restore community confidence in the police." The task force report (gallery below left) included the following recommendations:

- DPD leadership should make a public and meaningful commitment to uphold the "Law Enforcement Code of Ethics" (excerpted at right) and to discipline officers who violated the pledge in all circumstances, including the harassment of civilians during routine traffic stops

- Reduce deadly and excessive force through transformation of the Police Academy instructional curriculum for new officers to include subjects "other than the military aspect"

- Establishment of a civilian review board, because "it is inconceivable that the Police Department can investigate itself"

- Aggressive recruitment of more African American officers to diversify the police force

- Replacement of the office of a Police Commissioner, drawn from the ranks of law enforcement, with an oversight board consisting only of civilian administrators

- Abolition of the STRESS unit, "because of its entrapment methods of operation and its record number of killings of Black citizens"

The Michigan Chronicle, the city's leading black newspaper, also depicted the state of police-community relations as a virtual war zone in a 1973 series on "Police and the Black Community." Eleven years after white liberal police reformer George Edwards promised to build a bridge over the "river of hate" between the DPD and the black citizens of Detroit, the Chronicle observed that the "bridge between the police and the black community is a gap that threatens the peace and tranquility of the city." According to the series, regular law-abiding "citizens, Black ones in particular, make every effort to avoid 'contact' with policemen, fearing that an untoward but innocent move may result in a fusillade of police gunfire." The Chronicle also portrayed law enforcement officers as fearful and hostile toward the community they were supposed to protect, as police "frequently make their initial 'contact' with guns at the ready" because they believed that black criminals and political radicals might shoot them first. (While several DPD officers were killed in the line of duty in the early 1970s, this exaggerated fear also reflected the propaganda of the FBI and the DPOA union that a black power conspiracy of "urban guerillas" was plotting to murder law enforcement officers on a broad scale).

DPD: "Turnaround in the '70s"

The Detroit Police Department presented an alternative reality of itself as an efficient crime-fighting machine that protected and respected law-abiding citizens, had resolved the late-1960s racial crisis in police-community relations, provided unprecedented opportunities for black applicants to the police force, and quickly dealt with the rare cases of misconduct by its officers.

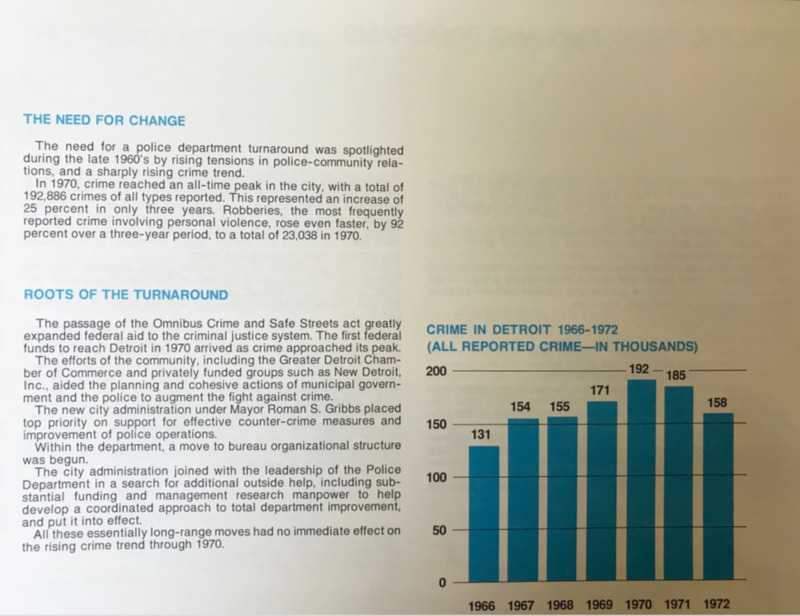

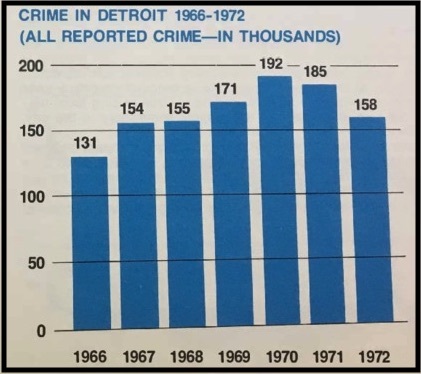

In 1973, at the height of the protest movement against STRESS, the public relations unit of the Detroit Police Department released a glowing booklet titled "Turnaround in the '70s" (reproduced in the above gallery). The DPD presented the reforms under the law-and-order leadership of Police Commissioner John Nichols and Mayor Roman Gribbs as a "drastic change of course" and a "turnaround of unprecedented scope and magnitude" from the late 1960s, essentially blaming the purported crime wave and previous police-community tensions on the policies of the liberal Cavanagh administration. The claim of a law enforcement turnaround rested most of all on misleading statistics that purported to show how STRESS and other aggressive programs had reversed the steady increase in all reported crime (right), which allegedly peaked in 1970 and then returned to the levels of 1967-1968 after two years of what the report called the comprehensive crime control measures of the Gribbs administration and the new DPD leadership under Nichols (and his successor Phillip Tannian, appointed in 1973 when Nichols resigned to run for mayor).

Note: The DPD and the city government had previously portrayed this late 1960s crime level as an out-of-control epidemic that required a dramatic police response, including the stop-and-frisk law, so the celebration of returning to it by 1972 is revealing and an obvious public relations tactic. It is also important to emphasize that this chart is based on total arrests, many of which did not result in prosecutions or convictions, and therefore measures discretionary law enforcement rather than actual "crime." The DPD's presentation of data in this format also conveys absolute numbers of reported crime, rather than the reported crime rate adjusted for population, which was declining rapidly in the city of Detroit during these years. It is also probable that crime reporting by victims decreased in the early 1970s as black residents in particular became alienated by STRESS and even more distrustful of the DPD. Widespread police corruption also allowed illegal drug markets to flourish, decreasing the official "crime" totals.

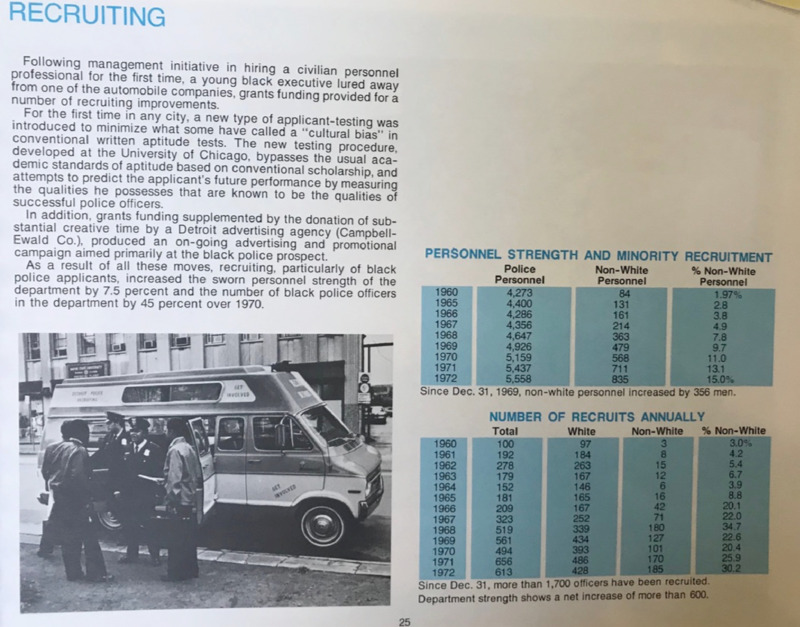

"Turnaround in the '70s" prioritized the crime control mission and had very little to say about police-community relations beyond the presumption that catching and incarcerating criminals through aggressive street policing would make the public appreciate the Detroit Police Department. The booklet credited the federal government for providing more than $10 million in grants to modernize DPD programs and enhance street-level enforcement through special operations that included narcotics task forces and the Stop the Robberies-Enjoy Safe Streets unit. The DPD also praised its increased response time to citizen calls for assistance, based on federal funding for new technology (subsequent investigations revealed that the city's 911 system was riddled with failures and that the department underpoliced drug markets and routinely ignored domestic violence and sex crimes against women). "Turnaround in the 1970s" further boasted that the DPD had eliminated the "cultural bias" in its application process and that the number of black officers had increased from 568 in 1970 to 835 by the end of 1972, representing 15% of the total police force [in a majority-black city].

The booklet even claimed that DPD's recently formed Internal Affairs Section, which had replaced the Citizen Complaint Bureau, dealt quickly and fairly with all allegations of police brutality and misconduct. Against all available evidence, the DPD declared that whenever "police misconduct, or worse, has been uncovered, the department itself has been responsible for the disclosures and corrective action." "Turnaround in the '70s" concluded:

Black Community Support for the War on Crime

Mainstream civil rights groups, along with government agencies such as the Detroit Commission on Community Relations and the statewide Michigan Civil Rights Commission, continued to promote the liberal police-community relations vision of fair and efficient crime control through the hiring of more black officers, implementation of human relations training, and community policing methods. Detroit's traditional civil rights organizations, most notably the Detroit Urban League and the NAACP, were oriented toward the concerns of middle-class black residents who self-identified as "law-abiding citizens" and wanted the police department to protect them from crime without brutalizing innocent people in the process. Unlike black power activists, these civil rights groups advocated procedural reforms through enhanced police-community relations programs and the racial diversification of the police force, which they believed would lead to a more effective war on crime.

The Detroit Urban League (DUL) was the most moderate and pro-police civil rights organization in the city. During the late 1960s and early 1970s, the DUL worked closely with the police department and black neighborhood associations to organize a series of "citizens' campaigns" to prevent and suppress crime. The Urban League repeatedly defended STRESS as necessary to deter the muggers and robbers who threatened law-abiding black citizens, while recommending that the unit's officers undergo psychological screening and include more African American policemen in order to reduce its reliance on deadly force. In 1973, at the height of the anti-STRESS campaign, Urban League leaders formulated a statement (left) that attributed the crisis of police-community relations equally to the brutal actions of some members of the DPD and to the "demagoguery of the extremists" (meaning black power groups) that made law-abiding black community members reluctant to report crime. The DUL argued that a quiet majority of black citizens in Detroit supported a fair and effective war on crime, desperately wanted to "enjoy peaceful neighborhoods [and] safe streets," and understood that "effective police work has its roots in effective cooperation with the community."

The Detroit chapter of the NAACP also supported the war on street crime while taking a more critical stance toward the Detroit Police Department than did the Urban League. At a 1972 mass meeting, for example, the NAACP rallied its members behind the war on drugs and called for immediate action to stop the muggers and narcotics addicts who threatened decent citizens on the streets (right). In January 1972, the Detroit chapter even gave its annual award for a white person who worked for the "elimination of racism" to DPD Commissioner John Nichols, because of the increased hiring and promotion of black police officers under his leadership. This decision to honor a conservative white police official was in part strategic, in the hope to accelerate the racial diversification of the DPD, given that Nichols always defended the police department against charges of brutality and led the opposition to a civilian review board, which the NAACP had long endorsed. The Detroit chapter of the NAACP filed multiple brutality lawsuits against the DPD during the period when Nichols was commissioner and also called for the abolition of STRESS in March 1972, arguing that the unit had created a crisis for police-community relations and that police officers guilty of using excessive force should be prosecuted. The NAACP advocated a more effective war on street crime through better training and psychological screening of police recruits, combined with a program to dramatically increase the percentage of black officers on the force.

Proceed to the next page for more information on the efforts to racially diversify the DPD and make the police force more representative of the population of the city of Detroit.

Sources:

Detroit Commission on Community Relations/Human Rights Department Records, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Bill Black, "Police and the Black Community" four-part series, Michigan Chronicle, Feb.-March 1973

Detroit Police Department Additional Papers (1965-1993), Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library

Papers of the NAACP, Part 29: Branch Department, Series B: Branch Newsletters, Annual Branch Activities Reports, and Selected Branch Department Subject Files, 1966-1972, ProQuest History Vault

Detroit Urban League Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan