DPD Homicides 1974-77

This page features 74 police homicides identified by our research team between 1974 and 1977, the time period covered in Section 1 of the Crackdown website exhibit corresponding to Coleman Young's first term in office. The homicides identified represent around three-fourths of total police-involved fatal force incidents acknowledged by the DPD, as detailed immediately below. This page maps and analyzes the key patterns in police homicides during this era and higlights key cases in a number of categories, including unarmed and fleeing suspects, teenagers, beating deaths, incidents resulting in civil lawsuits, mental health crises, plainclothes policing encounters, and officer self-defense claims. Off-duty police homicides are covered on the next page.

Overview of Police Fatal Force Data

Archival records located by our research team indicate that officers in the Detroit Police Department killed at least 100 civilians between 1974 and 1977. This total is undoubtedly an undercount. It is based only on the fatal police shootings acknowledged and documented in official DPD incident reports and investigative records. It does not include other types of fatalities from police-civilian encounters, such as deaths by beatings, deaths in custody from negligence or assault, or deaths from police-caused automobile accidents. Fatal encounters involving off-duty officers, who were required by DPD policy to carry firearms at all times, are also inconsistently accounted for in the data. The archival totals produced or drawn from government records also do not include the names or identifying details of individual homicides. Still, even though official totals vary, they provide a useful starting point for an accounting of fatal police force during Coleman Young's first term as mayor--the era that inaugurated "community policing" and the first four years of Black political control of the Detroit Police Department.

-

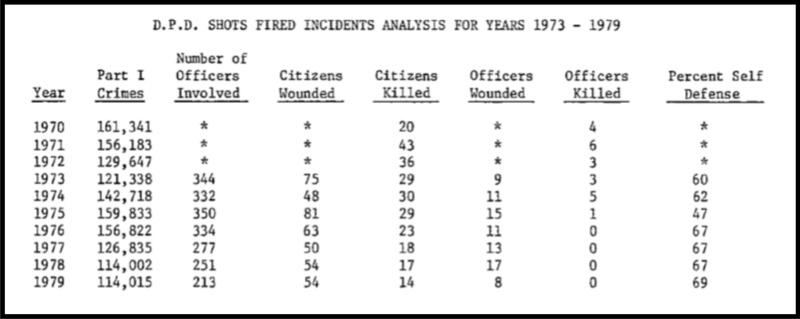

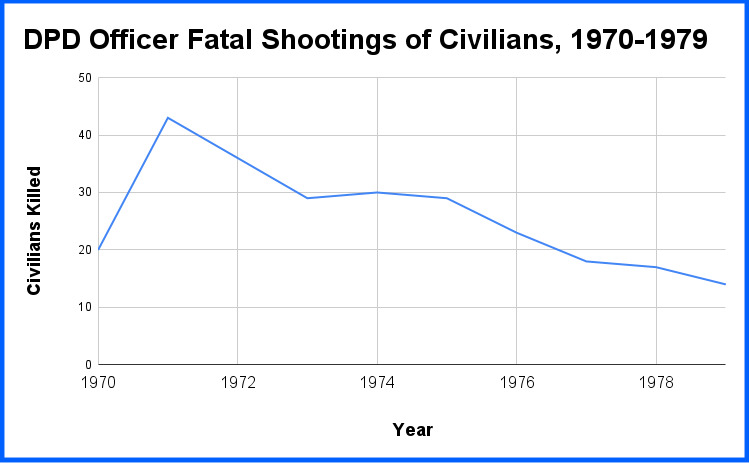

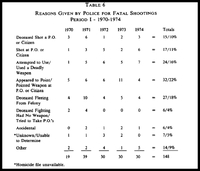

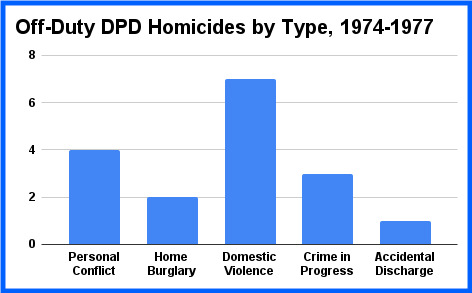

John Wesley Domm's 1981 dissertation at Wayne State University provides the most thorough data available in published or accessible archival sources, based on official DPD "shots fired" incident reports. Domm, a former Homicide Bureau investigator, completed the dissertation while actively serving as a DPD inspector and a lecturer in Criminal Justice at Wayne State. He received expansive access to internal DPD records and found that officer-involved shootings resulted in 100 civilian deaths and wounded another 242 civilians between 1974-1977 (above graphic), the time period covered in this section. This aggregate data includes both on-duty and off-duty officer-involved shootings--the DPD classified both categories as "in the line of duty."

Domm emphasized that fatal police shootings declined throughout the 1970s, which the report attributed to Mayor Young's abolition of the deadly STRESS unit and affirmative action policies, decreasing rates of violent crime, better use-of-force training, and the more restrictive use-of-firearms policy revision under Chief William Hart (covered on the previous page). It is important to note that this was a decline only from the extremely high spike in police homicides during the STRESS era of the early 1970s, as fatal-force incidents remained well above the annual average during the 1960s. Domm's study contended that policy violations and criminal conduct by police were "quite rare" in fatal shootings but also acknowledged that officers "tend to conceal evidence and facts which might incriminate them in disciplinary or court actions" (86).

- The DPD under Chief Phillip Tannian, Hart's predecessor, reported 45 fatal shootings by on-duty officers during 1974-1975 combined in response to an inquiry from Mayor Young's office (gallery below, at left). This report purported to show a decrease from the very high totals during the racially charged STRESS era, when Coleman Young and many other Black leaders and residents had protested police killings of unarmed Black youth. But the data in the Domm study makes clear that the DPD provided an undercount to the mayor, and that a meaningful decline in police homicides did not begin until 1976. Domm's study, based on internal incident reports, identified 59 police homicides during the same two-year period, 14 more than the DPD acknowledged to the mayor's office. The main discrepancy is because the DPD did not include off-duty officer homicides, even though the department required off-duty officers to carry handguns and be prepared for police action at all times.

- A major national use-of-force study published in 1983 by the National Institute of Justice (gallery below, middle) identified 36 fatal shootings by on-duty DPD officers during 1976-1977 combined, and another 5 homicides by off-duty officers. This total of 41 on-duty and off-duty homicides for this two-year period is very close to the data in the Domm report and indicates that the federally funded NIJ researchers received access to the same internal DPD records. The NIJ report credited the notable decline in fatal police shootings starting in 1976 to a range of factors, most prominently the DPD's introduction of a more restrictive use-of-firearms policy, although this did not take effect until January 1977.

The DPD acknowledged 45 homicides by on-duty officers during 1974 and 1975 combined, in this non-public response (and undercount) to the mayor's office.

A National Institute of Justice report identified 36 fatal shootings by on-duty DPD officers between 1976-1977, and 5 more by off-duty officers

Patterns of Police Homicides (DPD Perspective)

The typical police fatality during the mid-to-late 1970s involved a younger adult Black male in his twenties allegedly involved in criminal activity and alleged or confirmed to have been armed. This composite portrait, drawn primarily from police-generated reports and testimony, of course must be viewed with some skepticism. Our research team's analysis, contained in the section below, raises questions about 45 percent of cases involving police claims of self-defense, such as when officer reports followed the common script of claiming that a fleeing suspect appeared to make a sudden move toward a weapon or drove at them with a car.

The most comprehensive data on the circumstances of police homicides during the 1970s, based solely on records provided by the DPD, comes from a 1984 law review article by Professor Edward Littlejohn of Wayne State University. (Littlejohn also served as one of Mayor Young's initial appointees to the Board of Police Commissioners). Littlejohn's data covers the period from 1970-1980 and mostly matches the fatality totals in the Domm study (above), with an average discrepancy of around one per year. (Littlejohn identified 96 fatal shootings between 1974-77, compared to 100 by Domm). Littlejohn focused particularly on how the political changes of the mid-1970s--a Black mayor and police chief, affirmative action to hire more Black officers, emphasis on improved police-community relations, and stricter policies governing use of force--did and did not affect police killings of civilians. Littlejohn's findings revealed:

- The annual total of police homicides declined substantially, starting in 1976. DPD officers shot and killed an average of 29 people per year between 1970-1975, and an average of 16.4 people per year between 1976-1980. Littlejohn attributed this to the accumulating effects of the policy and cultural changes implemented by the Young administration.

- The general demographic and circumstantial patterns remained the same throughout the decade: the typical person killed by police was a younger Black male in his mid-to-late twenties, alleged or confirmed to have been armed. The Littlejohn study reported that Black individuals accounted for 81 percent of police homicide victims between 1970-1974 and approximately the same for the rest of the decade.

- According to police reports of these events, almost two-thirds of fatal shootings during the mid-to-late 1970s involved armed suspects engaged in dangerous or threatening behavior (see charts at right). Between 1971 and 1974, according to DPD reports, around 60 percent* of police shootings involved allegedly armed suspects, compared to 64 percent from 1975-1980. (*Note that police-reported data on armed suspects is unreliable because of the obvious incentive to portray questionable or unjustified shootings as justifiable. The Policing and Social Justice HistoryLab's analysis of DPD homicides during 1971-1973 found that only one-third of suspects were clearly armed, not 60 percent, and that a significant number were actually unarmed or the evidence was disputed, including a number of likely or verifiable cover-ups).

- The proportion of police homicides where the alleged suspect only "pointed" or "appeared to point" a weapon increased from 22 percent between 1970-1974 to 32 percent between 1975 and 1980. During the second time period, half of all officer self-defense claims involved this "pointed"/"appeared to point" scenario. The Littlejohn study did not interrogate this distinction, but one plausible explanation--addressed in the case studies below--is that officers who had previously enjoyed carte blanche to shoot unarmed fleeing suspects began to claim that the suspects appeared to be armed in their "split-second" judgment as the DPD tightened use-of-firearms authority in this scenario.

- DPD-reported shootings of "fleeing felons" who did not pose an imminent armed threat declined from 18 percent of total police homicides between 1970-1974 to only 8 percent betwen 1975-1980. This is likely a result of some changes in police culture based on leadership articulation of stricter use-of-force protocols and discouragement of firing against unarmed civilians, especially juveniles. It is also possible and even probable that in some cases, officers had the incentive to portray unarmed and deceased suspects as armed and dangerous because of the increased scrutiny of the "fleeing felon" scenario. Our project data (below the map) reveals that 40 percent of the cases where the DPD classified a fleeing suspect as armed and dangerous are actually in dispute.

- Littlejohn considered the decrease in fatal force against "fleeing felons" to be a major success for the community policing and affirmative action reforms of the Coleman Young administration. He also called for the Michigan state legislature to adopt the American Law Institute's Modern Penal Code, which would prevent the use of fatal force against suspects except in crimes involving attempted or actual deadly force--not burglaries or robberies. In fact, Littlejohn argued that shooting at a fleeing felon suspected of a nonviolent crime should be unconstitutional. (The U.S. Supreme Court did finally rule this scenario unconstitutional in the 1984 case Tennessee v. Garner).

- The DPD's internal investigation determined six police homicides to be "improper" between 1970-1974 and just two more between 1975-1980. (This data does not include officers who killed family members in domestic violence episodes). Only three of these cases resulted in arrests and criminal prosecution, with zero convictions at trial. This indicates that more restrictive use-of-force policies could decrease police violence, but that internal investigative procedures continued to be tilted toward exonerating officers even when they stretched or violated them.

Mapping 74 Police Homicides between 1974-1977

Researchers with the Policing and Social Justice HistoryLab have uncovered archival records for 74 police homicides in Detroit between 1974 and 1977. This represents around three-fourths of the semi-official total of 100 fatal shootings by DPD officers during this four-year period, based on the internal records provided to researchers John Wesley Domm and Edward Littlejohn and discussed above. Our investigation also uncovered two fatalities from police beatings and several other off-duty homicides involving domestic violence or personal disputes that are presumably not included in the DPD records of 100 civilian fatal shootings. One of the homicides in the dataset was committed by a Hamtramck officer inside the city limits of Detroit, and in another DPD and Highland Park officers were involved together.

The research team uncovered these cases primarily through laborious and systematic keyword searching in digitized newspapers and additional discoveries in the archival collections of Mayor Coleman Young and others. We focused first on the Detroit Free Press and Detroit News, the city's two mainstream daily newspapers, which generally printed a brief notice based on the police version of events when they even reported the fatal-force incident at all. In several controversial deaths, the team found more details in the Michigan Chronicle, Detroit's weekly Black newspaper, which was only available on microfilm when this research project began but was subsequently digitized and then researched again using keyword queries. In some cases, newspapers only wrote about police homicides several months or years after the incident, when families of victims filed or won civil lawsuits against the city of Detroit, an increasingly common occurrence during the 1970s. At times, family and/or community pressure caused the mayor's office or other elected officials to seek out the details of a police homicide, leaving accessible evidence in the archives publicly available to our project team.

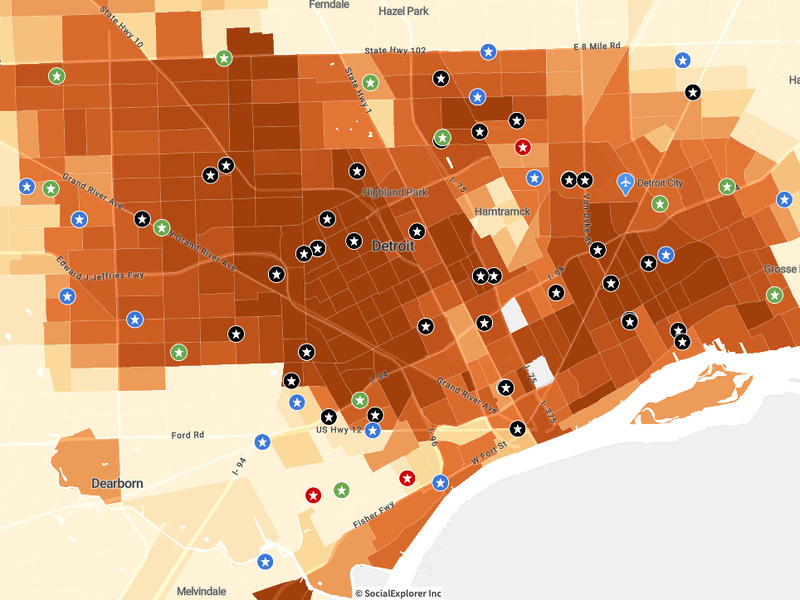

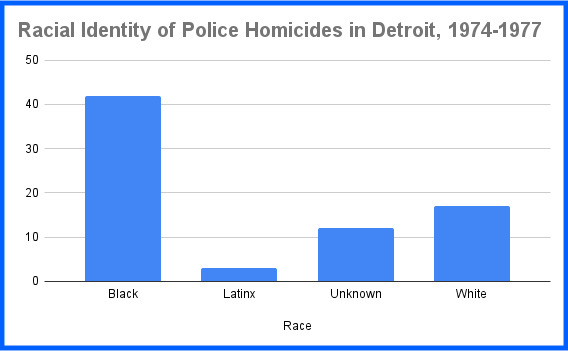

The map below displays the 74 police homicides uncovered by the research team by the racial identify of the deceased, located in the changing racial geography of the city of Detroit. The Detroit population shifted from 44.5 percent Black in 1970 to 63 percent Black by 1980, mostly due to white flight from the outlying city neighborhoods. Many of the homicides took place in areas undergoing rapid racial transition, especially in the formerly all-white bastions of Northeast and Northwest Detroit.

The research team hypothesized racial identity for a number of these cases, because the newspapers generally did not report the race of crime suspects or police shooting victims in the 1970s. We identified people as Black if they lived in overwhelmingly Black neighborhoods, and/or if the alleged crime took place in segregated Black areas. If the Michigan Chronicle reported and investigated the case, the homicide almost always involved a Black individual. We identified racially unmarked people as white if they lived in overwhelmingly white areas, but the mainstream newspapers also were much more likely to investigate in depth, and to include photographs of the deceased, if the police-involved shooting victim was a white person. It is probable that most of the cases where race is undetermined involved Black individuals, based on the overall trend that more than 80 percent of people killed by the DPD in the late 1960s and 1970s were African American. Two homicides in the undetermined group were possibly Latino.

Swipe the map to view the police homicides in the racial landscape of the 1970 and the 1980 census data. The darkest shades on the map represent the most heavily Black neighborhoods; hover over the census tracts to see the racial breakdown of each. Hover over the circles for a pop-up box with the date of the homicide, incident description, and source information. More detailed research findings and featured cases in a range of categories are below the map.

Map of 74 Identified Homicides by Police Officers, in Detroit's Racial Geography (1970 and 1980 Census)

- Black circles (42) = African Americans (67% of the total where race could be identified)

- Blue circles (17) = White (27% of the total where race could be identified)

- Red circles (3) = Latinx (5% of the total where race could be identified)

- Green circles (12) = Racial identity undetermined

Key Findings and Patterns

- "Justifiable Homicide" (95% of identified on-duty killings). The Wayne County Prosecutor, William Cahalan, found all but the three of the on-duty police homicides to be justified. Three officers faced manslaughter charges, but none was convicted. Two of these cases involved white victims; all three are featured below. In one case involving two officers, the DPD Homicide Bureau recommended indictment but the prosecutor refused. Five off-duty officers were also prosecuted for killings, all involving domestic violence.

-

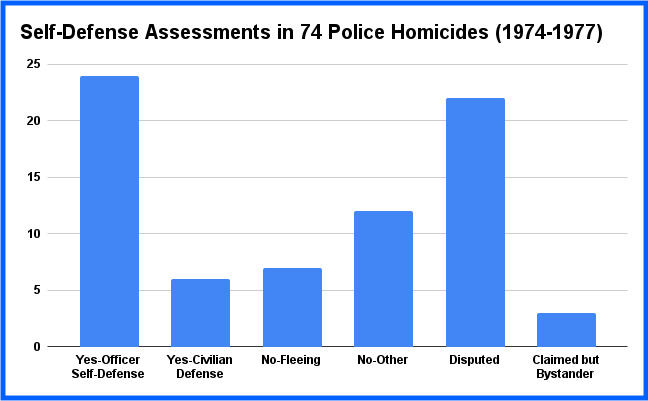

Self-Defense (41% verified; 23% disputed; 27% definitely unarmed). Official DPD records, reproduced above, claimed officers shot in self-defense or defense of civilians in around 65 percent of police homicides. Our review of the identified cases finds verified self-defense claims in 41% of the homicide total and disputed evidence in 23% of the total. Put another way, of the 55 cases in which officers claimed self-defense or defense of others, our review assesses that 30 of those cases (55%) are verifiable based on the data available, and 25 (45%) are in dispute. Most of the disputed cases--discussed in more detail in categories below--involve suspects shot while fleeing in cars or on foot, where the officer account follows the common script of claiming the car tried to hit them or the burglary suspect suddenly turned around and threatened them with a weapon. In three of the disputed cases, officers claiming self-defense shot innocent bystanders. In one case, the officer's claim was almost certainly fabricated.

- DPD Policy Violations (18% definite or probable; 39% debatable). A majority of police homicides either possibly or definitely violated the DPD's use-of-firearms policy, which became more restrictive in early 1977. DPD Homicide investigators and county prosecutors generally deferred to the discretionary authority and self-exonerating reports provided by officers who used fatal force unless evidence of their policy violation was egregious, in line with the national pattern by law enforcement agencies. The definite group (13 total) includes 6 domestic violence situations that resulted in criminal charges for the officer or ended in murder-suicide; 2 beating deaths; an officer prosecuted for firing into a crowd of teenagers at a bar. The project classifies four others--Jessie McKinney, George Adams, Leon Cockran, and Felix Medel--as policy violations in the fleeing and unarmed burglar scenario. Of the 29 cases classified as debatable policy violations, more than half involved suspects shot while fleeing on foot or in a car, when DPD regulations permitted fatal force only if there were no other way to prevent escape. In other debatable cases, officers opened fire on crime suspects, people involved in domestic disputes, or people experiencing mental health episodes without arguably making sufficient effort to detain them without lethal force. In four off-duty killings, officers claimed self-defense when they arguably escalated personal conflicts.

- Civil Lawsuits (13%). At least ten of the homicides resulted in wrongful death civil lawsuits that the City of Detroit either settled or lost at trial. All of these cases are featured below or on the off-duty homicides page. It's likely that several others resulted in civil litigation that the team has not identified.

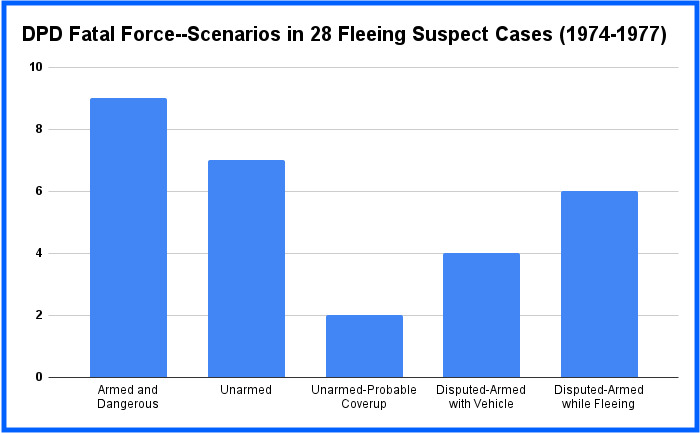

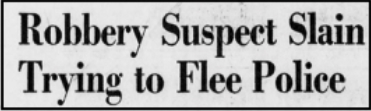

- Fleeing Suspects (38%). More than one-third (28 of 74) of the homicides involved suspects fleeing, or allegedly fleeing, when shot by police. Seven of the fleeing cases involved definitely unarmed victims, and our project determines that in an additional twelve cases, the officer's claim that the victim was armed and dangerous is in dispute. Most of these involved the common script of officers claiming that the driver fleeing in a vehicle tried to run them over with the car as a weapon (5 cases) or the suspect fleeing on foot from a burglary suddenly turned around and pulled out a knife or similar weapon (4 cases). In an additional three cases, the person was armed but did not appear to be posing any immediate threat when shot. In four cases discussed below--Jessie McKinney, George Adams, Leon Cockran, and Evelyn Neal--there was countervailing evidence that officers might have fabricated the armed and dangerous scenario. (One officer was charged, in the George Adams case). Only two of the questionable shootings of an unarmed or possibly unarmed fleeing suspect took place after the DPD policy change in Feburary 1977 to actively discourage fatal force in this scenario.

- Race (68 plus % Black). Two thirds of the homicides where race could be identified involved Black victims (42 of 62). White victims made up 27% where race was identified, and Latinos made up 5%. It's probable that most of the undetermined group were Black or Latino. It is very likely, since the media underreported officer-involved shootings involving Black suspects, that almost all of the homicide victims in the official DPD data that the research team could not locate were Black. Based on all available evidence, the Black total was probably above 80%.

- Gender (89% Male). Most (66) of the identified police homicides involved males, and it is probable that almost all of the unidentified ones did, because of how media coverage operated. Of the 8 identified female victims, five were Black women or children killed in domestic violence by off-duty officers. One 44-year-old armed woman was killed by police responding to an intimate partner conflict. One white teenager was shot in a fleeing car driven by the male suspect. Evelyn Neal, whose case is examined at length below, was a Black sex worker shot in questionable circumstances.

- Teenagers (18%). Youth age 19 and under accounted for 13 of the 74 identified police homicides. Six were age 16 or younger--a burglary suspect, a robbery suspect, two youths killed when officers fired at moving vehicles, and two young children murdered by their father. Three older teenagers were killed in controversial incidents involving alcohol, and three more as unarmed burglary suspects. The majority of identified teenagers were white, which may be related to whose killings made the newspapers.

- Location-Physical. Almost one-third (23) of the homicides occurred inside or right outside business establishments, including ten in bars. Half of the bar-related homicides involved armed robbery or fleeing burglars; in the remaining five, police killed bystanders or were prosecuted for their actions. Killings in other types of businesses generally involved police responding to armed robbery or burglary calls. Eight of the identified homicides happened during car chases. Seven happened outside homes allegedly burglarized. Of the twenty-one other homicides inside or right outside private homes, fifteen involved domestic violence, three were drug raids, and one was a response to a mental health call. Five other homicides in public places involved officers encountering armed criminal suspects; several escalated from routine traffic stops, or in one case the stop-and-frisk of a pedestrian.

- Location-Racial Geography. In general, the identified homicides shifted away from the downtown region, which the DPD targeted for preemptive policing during the STRESS era, toward outlying neighborhoods including racially transitional areas. Homicides of burglary and robbery suspects often happened in white or racially changing neighborhoods, probably reflecting both the traditional deployment of police resources to protect property in those areas and an artifact of whose deaths were reported in the media. Off-duty homicides by white officers almost always happened in the more racially segregated outlying areas where they lived.

- Mental Health (9%). Seven of the homicides involved mental health situations, and all seven victims were Black. In three cases where the need to escalate to lethal force seemed questionable, officers shot people allegedly armed with a knife, gardening tool, or small chain. One involved a dangerous barricaded shooter. One involved an officer who killed three family members then pleaded insanity.

- Drug Raids (4%). Only three cases involved drug raids of private homes, a scenario that would increase in frequency in coming years. All of the alleged drug dealers killed inside their homes were Black, and two appeared to be small-scale marijuana dealers.

- Bystanders (7%-9%). Police killed at least five, and likely seven, innocent bystanders. Three were patrons in bars when police officers fired at other people and hit them instead; one man was mistaken for a burglar when he was trying to help find the burglar; one teenage female was a passenger in a speeding car. DPD policy prohibited shooting "when there is any substantial danger to innocent bystanders." In two cases featured below--Jessie McKinney and George Adams--officers shot Black males in their 20s and claimed they were fleeing burglaries but the evidence indicates they were uninvolved. Both cases resulted in wrongful death settlements.

- Beatings (3%). In two cases, both featured below, officers beat civilians resulting in their deaths. The Thomas Bruce case resulted in acquital at trial, and the Bernard Miller case resulted in two officers being fired for a policy violation but not charged.

- Off-Duty Officers (23%). Off-duty officers were involved in 17 of the 74 identified homicides, almost one-fourth of the total. In a majority of off-duty shootings, the officer's actions were either clearly criminal or involved questionable claims of self-defense. Seven of the off-duty shootings arose from domestic violence situations; five resulted in prosecution--all involving Black officers. One officer was convicting of killing his girlfriend; one was found not guilty by reason of insanity for killing his wife and two children; another ended in murder-suicide; and one officer trainee was convicted for reckless endangerment. More than half of the off-duty shootings that were not domestic-violence related involved white victims. Two off-duty officers killed unarmed and fleeing burglary suspects; in four cases, the off-duty officer escalated a personal conflict by shooting an unarmed person. These six cases, most involving white officers/white victims and questionable circumstances, are featured in depth on the next page.

Featured Police Homicides by Category, 1974-1977

The remainder of this page features individual DPD fatal-force incidents including many that involved questionable circumstances, potential policy violations, and/or possible criminal action on the part of the police officer. It should be remembered that at least 41 percent of DPD homicides involved suspects who were "armed and dangerous," including a number of fatalities where the person killed or tried to kill civilians and in some cases police officers. All of these verified cases are viewable in the above interactive map, and some are also featured in the categories below. At the same time, as detailed above, our project assesses 26 percent of police homicides to be of unarmed people and 34 percent of the total to be self-defense claims that are debatable, often because the only evidence in the public record is a brief report of the officer's version of events.

Category 1: Questionable Cases: Burglary Suspects Unarmed or Allegedly Armed

DPD on-duty officers shot and killed at least ten unarmed suspects fleeing alleged burglaries of homes or businesses, and off-duty officer shot and killed two additional people. Almost all burglary fatalities involved young males in their teens or early twenties. Civil rights activists had long called on the DPD to ban the use of fatal force for unarmed and fleeing burglary suspects, especially juveniles, and Commissioner Hart tightened the policy in this scenario in 1977, while still permitting fatal force to prevent escape for a property crime that often resulted in a probationary sentence. Eight of these cases are profiled here, in chronological order.

Peter Whitehorn (July 24, 1974), Whitehorn, a 19-year-old male (race unknown) was shot and killed by Officers Harry Ramsey and Patrick Browne while unarmed and allegedly attempting to flee arrest as a burglary suspect. The officers claimed that Whitehorn shoved Officer Ramsey and then ran. Both officers fired and one shot hit Whitehorn in the abdomen. He died later at the hospital, and police later arrested an accomplice for the low-level crime of "breaking and entering." It is questionable whether fatal force was justified as "the only means of preventing the felon's escape," according to DPD policy at the time, but the only archival trace is the police department report reproduced in a small newspaper article.

Jesse McKinney (Sept. 12, 1974). McKinney, a 24-year-old Black male, was shot in the back of the head and killed by Officer James Anderson in a likely coverup that ultimately resulted in the city of Detroit paying a $90,000 civil settlement to McKinney's estate. Around 9:30 pm, Anderson and his parter responded to a burglary report called in by a woman in a racially transitional neighborhood. Anderson claimed that as he investigated on foot, "an individual lunged out from the darkness and slashed" at him with a knife, cutting his shirt. Anderson then claimed that the individual started running away and ignored an order to halt, so he fired at the suspect and killed him. Anderson further claimed that he found a knife on the ground near McKinney's body and put it in his pocket. While many parts of the story are dubious, for an officer to remove the knife from the scene of a homicide violated DPD policies on tampering with evidence as well.

Jessie McKinney's family filed a wrongful death lawsuit against Officer Anderson and the city of Detroit. The mainstream newspapers at the time barely covered the incident, just reproducing the police summary, but the Law Department's memo recommending settlement (at right) told a much different version of events. First, six witnesses deposed in the civil lawsuit--three inside the building where the alleged burglary was taking place, three on the porch of an adjacent house--all stated that they did not see or hear any evidence of a burglary in progress, they did not hear the officer call for McKinney to halt, and they did not observe the officer picking up a knife near the body as he had claimed. Additionally, Inspector Mary Jarrett of the DPD Crime Lab testified that Officer Anderson's shirt could not have been slashed with someone else's knife from the outside but had been cut evenly from the inside, implying that Anderson fabricated the scenario after the fact. (Jarret had famously uncovered forensic evidence proving that a white STRESS officer had planted a knife after fatally shooting a Black victim in 1973).

The Law Department recommended the $90,000 settlement in recognition that a jury would likely award the McKinney estate a much higher sum and that there was no evidence of a burglary. All of this contradictory evidence came out in the civil lawsuit but would have been available to the Homicide Bureau and Wayne County Prosecutor, had they done a thorough and impartial investigation, especially the findings of the DPD's own Crime Lab.

Final note: Jessie McKinney was a married father, recently laid off by Chrysler, who was separated from his wife and residing temporarily in the neighborhood with a friend. Since there was no evidence of burglary, it seems possible that a white resident called in the report after seeing an unfamiliar Black man in the transitional area, which shifted from 21 percent to 52 percent Black over the course of the 1970s, and the officer presumed his guilt and just opened fire.

John R. Calleja (June 29, 1975). Calleja, a 17-year-old Latino male, was shot and killed by Officer Ronald Connel after allegedly breaking into a West Side grocery store. Connel and his partner said that Calleja and an accomplice ran out of Nick's Market and ignored two warnings to halt. They chased for a block before Connel fatally shot Calleja once in the back.

George W. Adams Jr. (March 4, 1976). Adams, a 21-year-old Black male, was shot and killed by Officer Willie Doss while allegedly fleeing a break-in at a North End gas station in an incident that resulted in prosecution of the officer. Initial police reports said that Officer Doss, who was in plainclothes and an unmarked car, saw Adams running away and identified himself as police and told him to halt. They said that Adams turned around and “waved an unidentified object at Doss,” who fired in self-defense and killed Adams with a bullet to the head. The object was later identified as a wooden chair spindle, which Adams’s mother, Lillian Smith, said he carried for protection from dogs that ran loose on the street. Police had already arrested one suspect in the break-in, and Adams lived right behind the gas station, so it is possible even likely that they mistook an innocent resident for a suspect.

The autopsy report raised serious questions about the police account and showed that Adams died with a bullet to the back of the head. This and other evidence resulted in a manslaughter indictment of Officer Doss. In the preliminary hearing, Lillian Smith testified that her son left the house around 9 pm to go for a walk, asked if she wanted to join, and then she heard gunshots less than five minutes later. Several officers claimed under oath that Doss fired from very close range after Adams attacked him with the wooden club. But the medical examiner testified that the autopsy report showed that the bullet to the back of the head was from a fair distance away, not at close range, and that Adams was very inebriated (.22 blood alcohol content). A female officer on the scene, Brenda Tansil, said that she did not hear Doss identify himself as police and that the officer "ran at Adams" and initiated a scuffle before firing his weapon. Recorder's Court Judge Justin Ravitz ordered a full trial, but then the Michigan Court of Appeals ordered the indictment dropped, and the DPD returned Officer Doss to active duty. In 1979, three years after the incident, the Michigan Supreme Court reinstated the indictment and required a jury trial. There are no newspaper accounts identified of the trial taking place. Lillian Smith, Adams’s mother, filed a $5 million wrongful death lawsuit in 1976 that charged her son was never involved in a burglary and was “willfully, wantonly and maliciously as well as intentionally shot and killed without provocation.” The city settled the civil lawsuit for $150,000.

Kenneth R. McGowan (Sept. 4, 1976). McGowan, a 21-year-old male (race undetermined), was shot and killed by Officer Donald Peters while allegedly fleeing from an attempted robbery of a bar in Northeast Detroit. Two officers entered Guys and Dolls Bar after a citizen flagged them down claiming two people were about to rob the bar. Police said the officers saw McGowan and another man running out the back. Officer Peters claimed McGowan "reached into his waistband as if to draw a weapon" before Peters fatally shot him in the back alley, but no weapon was found on McGowan. McGowan had escaped from a state reformatory, Camp Pontiac, days earlier.

Felix Medel (Oct. 2, 1976). Medel, a 30-year-old Latino, was shot and killed by Officer Daniel Hughes, who said he mistook Medel for a burglar. Two daughters of Mary Kelley called police after hearing a noise and seeing a shadow outside their house in Northeast Detroit. They also called their mother, who was at a nearby bar. Mary Kelley and Felix Medel, a friend who was at the bar with her, returned to the house. When Hughes and his partner arrived, the daughters said someone was still in the backyard. Officer Hughes "saw someone crouched down in the yard" and fired two shots, killing Felix Medel, who was only looking for the burglar. There is no record of more than a pro forma investigatuion although the shooting appeared to violate DPD policy since Medel was not fleeing or armed and could have been detained without being shot.

William Alonzo Dougherty (Dec. 30, 1976). Dougherty, a 23-year-old Black male, was shot and killed by Officer Dennis Bielskis, part of a plainclothes team staking out a downtown intersection to look for Dougherty as a robbery suspect. According to the police report, Bielskis opened the driver’s side door and ordered Dougherty to get out of the car. The information released by the Homicide Bureau, as reproduced in the Detroit Free Press, said that Dougherty “attempted to drive away” and then Bielskis shot him “in the back of the head when the man attempted to grab the policeman’s drawn revolver.” The Detroit News reported that Bielski fired after Dougherty tried to reach for a gun that he had in his own belt. It’s not clear how a suspect could be simultaneously attempting to escape in a car, possibly grabbing a police officer’s gun, posing an immediate threat, and be shot in the back of the head. Additionally, the police knew Dougherty’s home address and so, if he was fleeing, could have sought to arrest him there. This case raises questions about whether the shooting, as opposed to the police report of the shooting, conformed to department use-of-firearms policy, but there is nothing else to go on in the public record besides two short newspaper articles that just reproduced the version the police department released to the media.

Edward Gaston (Nov. 29, 1977). Gaston, a 23-year-old Black male, was shot and killed by Officer John Wolff of the Tactical Services unit while allegedly fleeing a home burglary in a Black neighborhood on the West Side. A neighbor called police after seeing Gaston and an accomplice breaking into the front door of the home. Officer Robert Smith said that he entered the front door, and Gaston ran out the back. Officer Wolff, waiting in the backyard, claimed that he ordered the suspect to stop and then fired when Gaston “reached toward his waist as if he was grabbing a pistol.” Gaston was unarmed. The Detroit News publishes a photograph of Gaston’s body on the ground with a group of police officers standing around talking. The newspapers only published brief reports based on the police version of events. The encounter follows the general formula of police claiming after a fatal-force shooting that the fleeing suspect appeared to reach for a weapon, therefore justifying the officer’s use of force against an unarmed person because of the “reasonable” fear of self-defense. This raises questions about whether the homicide actually did comply with the DPD’s new use-of-firearms policy, but there is nothing in the public record beyond the police account.

Category 2: Fatal Shootings of Teenagers by On-Duty Officers

Police officers killed 13 teenagers or younger children between 1974-1977. Six of this group were killed by off-duty officers and are featured on the following page, and two fleeing burglary suspects are in the previous category. The other five teenagers fatally shot by on-duty officers are below.

Gerald (Jerry) Orth (Nov. 22, 1975). Orth, a 17-year-old white male, was shot and killed by Officer Hozie Reese during a conflict between a group of underage white teenagers and Reese, a Black officer, at the Bedford Inn bar in a white area on the East Side. Reese and partner Joe Grayer Jr. arrived in plainclothes around midnight as backup for white officers seeking a robbery suspect. The white youths tried to hide in the bathroom because they were underage. Several of the white youths admitted that a friend of Orth's, 17-year-old James Tocco, said "that n***** out there is a cop,” referring to Grayer. The white youths said the fight began when Officer Reese, who was in the bathroom at the time, hit Tocco repeatedly with a flashlight in response. Then one of the white youth (neither Orth nor Tocco, according to witnesses) hit Reese in the head with a beer bottle. It is not clear if any of them knew that Reese was a police officer, and there is no evidence that Jerry Orth said or did anything to the officer. Reese said that he fired his gun in self-defense into the "gang" of youths attacking him, killing Orth. Orth’s family demanded prosecution and said that Reese had murdered Jerry Orth “for absolutely no reason.” Orth was a football star at a Catholic school in Detroit, and two of the white youth involved were the sons of police officers. The Wayne County Prosecutor charged Reese with manslaughter and assault, stating that the death only occurred because of his anger toward Tocco for the racial epithet. Reese testified at trial that he was attacked by a "lynch mob” and that the white youths said “kill the n*****.” He was acquitted by a mostly Black jury that accepted his claim of self-defense. After a nearly two-year suspension, a police trial board absolved Reese for the fatal shooting, although he pleaded no contest (in the internal proceeding) to beating a prisoner for his conduct toward Tocco and received a 25-day backdated suspension without pay.

Rita Grochowski (Nov. 27, 1975) Grochoswki, a 16-year-old white female and high school senior, was shot and killed by Officers Lawrence Trent and Paul Arreola as police attempted to stop a speeding vehicle, in which Grochowski was a passenger, on the West Side. Both officers fired after Larry Joe Hollander, the 27-year-old man driving the vehicle, failed to stop when instructed, police said. After the car crashed, Grochowski was found dead with a bullet wound to the head. The driver, who police said had been drinking, was charged with felonious assault with a vehicle for allegedly attempting to run over Trent and Arreola. Without this charge, the shooting likely would have violated DPD policy because the driver was not fleeing an underlying felony known to the officers, and the gunfire risked injury to an innocent third party.

Anthony Miller (Dec. 15, 1976). Miller, a 16-year-old male (race unknown) was shot and killed by Officer Ronald Martin after Miller allegedly attempted to rob a pizza delivery worker with a BB gun in Northwest Detroit. The pizza restaurant recognized the voice of the caller as someone who had robbed the same delivery worker a couple weeks prior, and so Officer Martin rode along to confront the robber, with his partner providing backup in an unmarked car. Miller allegedly jumped from behind the bushes and tried to rob the delivery worker. The Homicide Bureau said that Martin ordered the teenager to drop his weapon and instead he threatened to kill the delivery worker, so Martin shot and killed him. There is nothing to go on but the police account reported in the newspapers, and no indication that reporters sought to identify the delivery worker as a witness. It’s uncertain why a juvenile engaged in holdups for a small amount of cash would threaten to kill someone else while a police officer held a gun on him. Martin was a former STRESS officer acquitted of assault with intent to kill in the infamous Rochester Street Massacre of 1972.

Malcolm Roger Smith (Jan. 12, 1977). Smith, a 16-year-old Black male, was shot and killed by Detroit and Highland Park officers following a vehicle chase in which Smith was driving with his cousin Larry McClung, a 20-year-old prison escapee, in the passenger seat. McClung had escaped from Jackson Prison the previous October, and police searching for him tried to stop the car that Malcolm Smith was driving. Investigators said that the driver of the car led police on a high-speed chase, rammed police cruisers set up as a roadblock, and injured multiple officers. Then, police said, officers from both departments began shooting at the fleeing car after the driver tried to run them down, killing Malcolm Smith. After the shooting, McClung successfully pretended to be his younger brother, and the newspapers reported that police investigators believed that officers had shot Malcolm Smith in a case of mistaken identity. McClung, still posing as his brother, then alleged to newspaper reporters that a police officer had executed his cousin in a parked car and used racial epithets. He did not tell this story to the police, and other witnesses did not see anything to this effect. A week later, McClung turned himself in after an anonymous tip alerted the DPD to the impersonation.

John Walker Jr. (Oct. 14, 1977). Walker, a 15-year-old male (race undetermined) was shot and killed by an unnamed police officer after he allegedly burglarized a Northwest Detroit home and "briefly held" a 12-year-old girl at gunpoint. Walker, who was from Pontiac, was in the house when the girl and her sister returned home. When police arrived, Walker fled out the back and was shot by an unnamed officer after he allegedly disobeyed orders to drop a gun and knife. Investigators alleged that Walker "turned on police with gun in hand." There is nothing in the newspapers except the brief police report released to the media, making it difficult to assess whether officers could have detained the young suspect without fatal force. The killing took place in a racially transitional neighborhood.

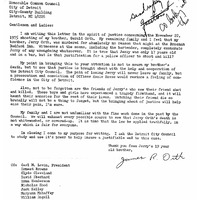

Category 3: Fatal Shooting of a Downtown Sex Worker

Evelyn Neal (August 18, 1974). Neal, a 50-year-old Black female, was shot and killed by Officer Larry Carter in downtown Detroit after an apparent dispute with a customer over payment for sex work. Neal and a companion, Rosetta Austin, were drinking in a bar with a 63-year-old man named Hubert Hedden and then left the premises. According to an investigation by the Board of Police Commissioners, “it appears that Mr. Hedden attempted to back out of an agreement to engage in a sex act for which Ms. Neal was to receive payment and that the two women attempted to forcefully collect the money.” Both women pulled out knives, slashed Hedden several times, and he fled into a nearby store whose manager called the police. Officer Carter and his partner, Lloyd Jones, arrested Rosetta Austin and ordered Evelyn Neal to surrender her knife. Neal allegedly refused and, according to the police officers and some, but not all, of the eyewitnesses, moved toward Officer Jones “in a threatening manner” and “continued to slash and stab at him.” Officer Carter then fired a single shot from his personal department-approved .357 magnum, striking Evelyn Neal in the back, and she was pronounced dead at the hospital.

The DPD’s Board of Inquiry exonerated Officer Carter, and Prosecutor William Cahalan declared the shooting to be justified. George Neal, Evelyn’s brother, filed a complaint with the mayor’s office alleging that Officer Carter had encounters with Evelyn Neal multiple times before the shooting and had previously threatened to kill her. The DPD did not respond to the inquiry from the mayor’s office, which next asked the Board of Police Commissioners to investigate. The BPC report (at right) labeled Neal a “known prostitute” who had been arrested almost 100 times, including six felony convictions. The BPC inquiry could not confirm George Neal’s allegation and did not contradict the prosecutor’s decision to exonerate. But the BPC strongly criticized the DPD Board of Inquiry for not acting on the ballistics evidence that Officer Carter had used a “half-jacketed” bullet, designed to expand upon impact and prohibited by department policy, in his personal .357 magnum. The BPC also recommended that the DPD improve its training so that officers would develop “techniques and skills for disarming knife-wielding assailants by non-lethal means.”

The Michigan Chronicle investigated the incident, interviewed multiple eyewitnesses, and reported major discrepancies in the police version of events. The official police report claimed that Neal “lunged at” Officer Jones with the hunting knife, causing Officer Carter to fire the deadly shot. The Chronicle found:

- The Wayne County Medical Examiner’s autopsy report showed the entrance wound to be on the left upper back with “no evidence of close range firing,” indicating the possibility that the officer actually shot Neal as she was walking away (Officer Carter, however, stated that he had to maneuver for a better angle before shooting in order to avoid harming bystanders, which could explain the back entrance wound)

- Many people witnessed the encounter because of a Masons convention happening across the street. The witnesses interviewed by the Chronicle differed on whether Neal was “attacking” the officer or "walking away," but all of them agreed that “they didn’t have to kill her”

- One Black minister at the Masons convention, who initially contacted the Chronicle to report possible police misconduct, stated that Neal tried to pull her companion away from the officer who was enacting the arrest, and “she had a knife out, but she did not ‘lunge’ at the policeman.” This witness, and other contradicting witnesses, were not mentioned in the Board of Police Commissioners investigatory report.

- Anonymous police officers contacted by the Chronicle (almost certainly Black officers) said that the DPD’s use-of-firearms policy needed to be changed. One said, “I don’t understand how, with all the manpower we have downtown, the arrest could not have been made without anyone getting hurt”

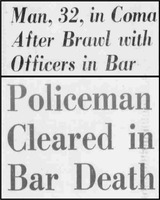

Category 4: Beating Deaths

Thomas Bruce (July 6, 1974). Bruce, a 32-year-old white male, died on October 21, 1974, almost four months after undercover officers from the Morality Squad beat him while investigating illegal after-hours liquor sales at the Tip-Top Inn in Northwest Detroit. Bruce was a general foreman at Ford Motor Company and lived in nearby Dearborn. The three undercover officers claimed that Bruce and four other patrons attacked them after one of the officers bought a drink after closing time, which the bartender denied happened, and then sought to clear the establishment. Police claimed that Bruce punched Sgt. Louis Fithian in the face and a brawl ensued. Officer Michael Matuzak acknowledged then beating Thomas Bruce with a gun, flashlight, and police radio, sending him to the hospital with a fractured skull.

Several bar patrons, who were arrested and charged along with Bruce but acquitted in a jury trial, said that Matuzak joined by other officers beat and kicked Bruce for around eight minutes after he tried to defend a drinking companion, Michael Pelton, who was being pistol-whipped by the cops. (Pelton also accused different officers of beating him later in the precinct station). Thomas Bruce, before slipping into a coma, told his mother that "I didn't do anything but defend a friend."

Bruce's family retained prominent civil rights attorney Kenneth Cockrel, filed a $3 million civil lawsuit, and said he was "beaten senseless in an unbelievable act of police brutality." The Wayne County Prosecutor charged Officer Matuzak with involuntary manslaughter based on the testimony of seven witnesses, including the bartender, who all told similar stories of extreme and extended assaults by police on Bruce and other patrons. The officers acknowledged under cross-examination that they had been drinking alcohol while on duty before arriving at the Tip Top; Sgt. Fithian said he had four shots of whiskey and Matuzak had "at least four" drinks. Matuzak said that despite DPD regulations, "there is an understanding" that Morality Squad officers were allowed to drink on the job. Judge Samuel Olsen, a former prosecutor, acquitted Matuzak in a bench trial and ruled that it was an "excusable and justifiable homicide" because Bruce was the aggressor. It is very difficult to square this verdict with the evidence; even if the patrons were initially the aggressors, which is disputed, the police officers beat Bruce so extensively and for so long that their retaliatory actions clearly continued after he posed no threat. In 1978, the City of Detroit settled the civil lawsuit filed by Bruce's family for $650,000.

The Thomas Bruce case is one of the few police homicides not linked to off-duty domestic violence that resulted in prosecution during this four-year period, and it is relevant that 1) the victim was an employed white man who lived in the suburbs and 2) there were multiple witnesses, also all white, who directly contradicted the police story. Still, the fact that the Wayne County Prosecutor's office agreed to a bench trial instead of a jury trial, with the case assigned to a former chief prosecutor, raises questions about legal strategy and how much the state's attorneys really wanted a guilty verdict. By only charging Matuzak, the prosecutor also allowed the defense to create reasonable doubt as to which police officer's blows caused the actual death. During the initial legal proceedings, Kenneth Cockrel tried to obtain access to the Citizens Complaint Bureau files for the three undercover officers, but a different judge denied the request. (Officer Matuzak also shot and killed a man in a murky incident in January 1974, claiming that the deceased pulled a "small hatchet from under his coat").

Kenneth Cockrel, a radical Black attorney, used the Thomas Bruce incident to criticize Mayor Coleman Young and the recently established Board of Police Commissioners for failing to curb the brutal police culture of the DPD. In July 1974, Cockrel demanded that Young "commit himself to the responsibility of effective citizen redress against illegal actions by police officers." He further called the BPC "dysfunctional--it doesn't operate. It is a charade that it is the final arbiter of complaints involving the Police Department." In 1976, after the acquittal of Officer Matuzak, Cockrel lambasted the Wayne County Prosecutor for its weak efforts to win the case and also said that the entire saga showed that "working class [white] people are subjected to the same treatment" from police as Black citizens and other racial minorities.

Bernard Miller (April 20, 1977). Miller, a 26-year-old Black male, died from injuries apparently sustained in a beating by Officers Norman Ide and Norman Taube, both white, who later were fired for failing to ensure adequate medical care for their prisoner. The patrol team responded to a call where Miller and his brother-in-law were fighting, left the scene when things seemed to be calm, then returned after a second call that Miller was breaking windows in his relative’s apartment. The police report said that Miller attacked the officers, so they had to subdue him. Witnesses confirmed that Miller was inebriated and had scuffled with the officers, but several said that the policemen kicked Miller around 10 to 15 times after he was already subdued and lying on the ground. EMS responded to the scene and recommended taking Miller to the hospital, but the police officers said that he did not need medical attention and instead took their prisoner to the 5th Precinct station. Miller was charged with malicious destruction of property but not, curiously, assault of a police officer. Miller was placed in a holding cell a little after midnight on a Wednesday evening, “hysterical and incoherent” according to police investigators, then found unresponsive in the cell on Thursday around 11 am and taken to Detroit General Hospital. Miller died of a fractured skull four days after the incident.

The autopsy conducted by the Wayne County Medical Examiner classified the death as a homicide based on blunt force trauma to the head. The investigation was inconclusive as to whether the injury that killed Miller happened outside the apartment or while in custody in the Fifth Precinct cell. Homicide investigators introduced doubt by publicly proposing the implausible scenario that Miller might have sustained the head injury in the fighting before the police arrived.

In December 1977, eight months later, the DPD fired Officers Ide and Taube after the police trial board determined that they had filed false reports and acted with negligence in refusing to transport Bernard Miller to the hospital. In the inquiry, Officer Ide acknowledged striking Miller with a blackjack, but the trial board found that the officers used “reasonable force” to subdue him at the scene. However, it emerged that the officers had resisted the EMS request to transport Miller to the hospital because their shift was almost over and they did not want to escort the ambulance. As policy, EMS were not allowed to transport a police prisoner without an officer escort, so Ide and Taube instead took Miller to the precinct station and then falsely told the desk sergeant that EMS determined the prisoner was OK.

The Internal Affairs division said the termination of the officers was a necessary part of the “cleanup” of the Fifth Precinct, which was dominated by white officers and had been the leading precinct for civilian brutality complaints for several years running. Officers Ide and Taube took the case to arbitration under the union contract, however, and were reinstated by a mediator. Bessie Miller, the mother of Bernard, filed a civil lawsuit that resulted in a $310,000 settlement with the City of Detroit in 1979.

Category 5: Additional Cases Resulting in Civil Lawsuits

At least ten police homicides resulted in wrongful death civil litigation. Four are profiled above, and this section covers two additional on-duty police homicides resulting in civil settlements. Four more cases involving off-duty officers are included on the next page.

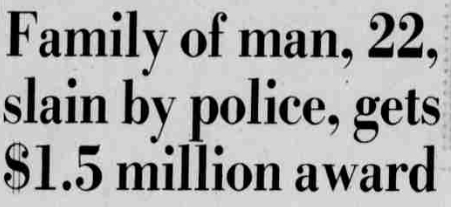

Larry Gates (Nov. 8, 1976). Gates, a 22-year-old Black male, was shot and killed by Officer Alford Wilson during an argument with his common-law wife, Theresa Smith, near a Northeast Detroit bus stop. Wilson and his partner, Sgt. James Younger, were in plainclothes and on patrol in an unmarked car when they noticed a woman shouting at a man and confronted him. Wilson claimed that he fired because Gates reached into his pocket did not take his hand out when instructed, and “made motions as though he might have a weapon in his pocket.” Gates was actually unarmed. Theresa Smith denied that she and Gates were physically fighting or that she was shouting at him. The police trial board cleared Officer Wilson. Gates’s mother filed a wrongful death lawsuit against the City of Detroit and was awarded $1.5 million by a jury in 1981 for Wilson’s “willful and wanton misconduct.” Witnesses in the civil suit said that Gates appeared confused by conflicting orders being yelled by the two officers, and the plaintiff’s attorney accused the police department of “grossly inconsistent” reports of what Gates was actually doing to justify any claim that officers acted in perceived self-defense. The city appealed the verdict but lost and eventually had to pay out more than $3.4 million including interest and attorney’s fees.

David Arthur Field (Jan. 19, 1974), Field, a 20-year-old white male, was shot and killed by Officer James Palms and Ross Arena of the 4th Precinct during a traffic incident. The officers claim to have stopped Field, a resident of suburban Dearborn, for a faulty muffler when he allegedly attempted to drive away and lost control of his car. The officers alleged Field tried to run Arena over and proceeded to fire into the vehicle, Arena twice and Palms three times. Field was killed by one of Palms's shot to the temple. Field's mother filed a $1.2 million wrongful death lawsuit.

Category 6: Mental Health Crises

Four police homicides featured in this section, all of Black males, involved probable or definite mental health crises. (It is quite possible that other fatal shootings between 1974-1977 involved mental health crises unreported by the police or media). These tragedies, most avoidable with better training and policies, actually represented a decrease from the seven people killed by police between 1971-1973 inside their own homes during mental health episodes. In February 1973, Police Commissioner John Nichols acknowledged that the DPD provided no training for officers in how to respond to mentally ill people and "we have neither the non-lethal weapons nor the expertise necessary."

In 1974, the DPD updated its policy toward "mentally ill persons" to conform to a new state law allowing police officers to take someone into protective custody if they had not committed a criminal act but appeared to pose a serious threat to themselves or others. But the policy did not address the recurring problem of police responding with fatal force in mental health situations where the person could legally be classified as a threat but was not armed with a gun and likely could have been subdued by less lethal means. Police officers generally argued that responding with force was necessary because of a number of high-profile cases where mentally disturbed persons had killed or wounded responding officers in the 1970s. Only one of the four cases featured below involved someone armed with a gun, and that person was on the street because of an institutional DPD failure caused by a lack of coordination with the state psychiatric hospital.

Jeffrey Taylor (April 6, 1974). Taylor, a 21-year-old Black male and unemployed autoworker, was shot three times and killed by Officer Lee Davidson during an apparent mental health crisis. Taylor was disrupting traffic on Grand River Ave. when Officer Davidson responding to a call of the incident approached him to make him stop. Taylor was allegedly swinging a two foot length chain. Officer Davidson returned to his car to call for assistance when Taylor approached him with the chain. Davidson fired his personal 9 mm semi-automatic pistol at Taylor three times, twice in the chest and once on his right arm. Taylor had a history of mental health problems, and his mother said she had tried unsuccessly to obtain assistance from psychiatric hospitals. The Michigan Chronicle reported that the chain was only 3/16 of an inch in diameter and not clearly a threat. Commissioner Tannian said "there are serious questions that need to be answered" about how DPD officers acted in response to mental health crises, but the investigation cleared Davidson of wrongdoing.

Charlie Richardson (Sept. 22, 1975). Richardson, a 48-year-old Black male, was shot and killed by Officers Alvin Banks and James Hamilton in his own residence during a mental health crisis. Richardson's family obtained a court-ordered psychiatric examination, and a city doctor called the police when Richardson refused to go to the hospital. The police broke into his apartment with the family's permission, and Richardson allegedly attacked Office Charles Key with a scythe or similar gardening tool, knocking him to the floor. Officers Banks and Hamilton then killed Richardson with multiple gunshots.

Chauncey West Jr. (March 3, 1976). West, a 28-year-old Black male, was shot and killed by a police sharpshooter during a standoff at a Midtown hotel that involved more than 100 officers. Armed with a rifle, West was staying at the Addison Hotel and when its owner opened his door after checkout time, West shot the man in the chest. After the owner called police, West barricaded himself on the sixth floor. Police chaplain Rev. William Paris attempted to speak with West, but West shot Paris in the head. West also shot an officer who attempted to rescue Paris, who died two days later in the hospital. Police charged the hotel, releasing tear gas, and West fled to the roof, where he was shot and killed by a police sniper. West was mentally ill and had stays in detention centers and mental institutions, including in 1975 after being found not guilty by reason of insanity for arson. The DPD was supposed to arrest West after his release from the institution to face an assault with intent to kill charge, but neglected to do so because of a "mix-up." West's family said that his mental health issues developed during his time serving in the Vietnam War.

Archie Muse (May 25, 1977). Muse, a 29-year-old Black male, was shot and killed by Officer Kenneth Grimm as Muse allegedly ran towards two police officers holding a knife in a probable mental health episode. The Homicide Bureau said that Muse was bleeding inside the bathroom of an East Side gas station when the manager called the police. Muse reportedly advanced on Officer Jerry Kuchinski, yelling and "waving the knife," and then Grimm shot him once in the chest.

Category 7: Dangers of Plainclothes/Undercover Policing

At least eight, and likely more, of the 57 on-duty police homicides identified were committed by undercover or plainclothes officers. This section profiles three homicides where plainclothes/undercover officers killed civilians, none of whom were engaged in criminal activity, in situations that escalated because the people involved did not realize that police were on the scene. The Larry Gates case, in category 5 above, also potentially involved this scenario of unidentified plainclothes officers.

When police officers are not in uniform, there is recognized significant risk that civilians will mistake them for armed criminals. This periodically results in civilians firing at undercover or plainclothes officers and sometimes killing them, officers firing at civilians who might have taken different action had they realized they were dealing with a police officer, or officers firing at other officers in '"friendly fire" scenarios. For an investigation of these broader patterns, visit the Policing and Social Justice HistoryLab's special report, "Cops or Robbers? The Dangers of Invisible Policing."

In 1976, Police Commissioner Tannian issues a new policy directive, "Proper Identification of Members" (at right), to address the problems caused by violence from situations where the general public did not realize they were dealing with plainclothes or undercover officers. The notorious STRESS operation, which Mayor Coleman Young disbanded, had brought scrutiny of undercover operations after its decoy unit killed 14 people between 1971-1973 and another STRESS team fired on off-duty Wayne County sheriff's deputies in the Rochester Street Massacre. The 1976 policy update required plainclothes officers, whether on duty or off duty, to "first properly identify themselves before taking police action." Otherwise, the policy warned, civilians might mistake officers for criminals and resist or even fire weapons at them.

Walter Brown (March 11, 1974). Brown, a 46-year-old Black male, was killed during a shootout inside a bar that he owned, the Blue Flame Lounge, after he mistakenly thought that two plainclothes officers were holding up the place. The officers, Gerald Morrison and Franscott Fowler, entered the bar in pursuit of a man they thought was a criminal suspect. Brown shouted “it’s a holdup” and shot at Officer Morrison, who was killed by three gunshot wounds. Officer Fowler fired at Brown, killing him, and also wounded Roosevelt Currie, a bar patron. Brown fired at Officer Morrison before the policemen had identified themselves, but Officer Fowler claimed that he then identified himself as a police officer and shot as Brown pointed a gun at him. Both officers were Black. Police Commissioner Tannian announced that no charges would be filed and that the plainclothes officers had “used proper procedure.” The officers' actions likely would not have been "proper procedure" under Tannian's 1976 policy revision, however.

Harold Jaynes Jr. and Gary Stang (Sept. 26, 1974). Jaynes, a 29-year-old white male, and Stang, a 33-year-old white male, were bystanders killed by police gunfire during a holdup at a crowded bar in Southwest Detroit. Four plainsclothes officers of the 4th Precinct's Morality Squad were inside conducting an investigation when an alleged holdup occurred. The undercover officers claimed that they identified themselves as the bar owner struggled with one of the robbery suspects and ordered everyone to get on the floor. One of the suspects allegedly fired a shot from the back door and then Officer Stanley Thompson and Officer George Lott each fired four shots towards the back of the bar. Jaynes Jr. and Stang were struck and killed by police gunfire when they were apparently standing near the back, possibly trying to escape through the side door. Police sources deflected responsibility by telling the newspapers that the two men should have complied with the shouts of plainclothes officers to hit the ground, although the scene was undoubtedly chaotic. Both men were truck drivers who lived outside Detroit, Jaynes in River Rouge and Stang in Sidney, Ohio.

Category 8: Spectrum of People Armed or Allegedly Armed

According to the DPD, 65 percent of homicides involved "armed and dangerous" suspects and police officers who fired in self-defense or defense of others. In our dataset of 74 identified homicides, self-defense claims by police accounted for 55 cases total. Our research project assesses 30 of these self-defense claims to be verifiable and 25 of them to be debatable. This is not an accusation that officers acted improperly but rather a commentary on the inadequacy of public records of police violence, the clear tendency of officers to follow self-defense scripts when they shot at people in cars or alleged suspects, and the documented pattern of internal investigators and prosecutors finding almost all police homicides to be justified unless the conduct was especially egregious or the forensic evidence overwhelmingly contradictory.

A number of self-defense claims that our project assesses as particularly debatable or likely fabricated are featured in categories above or on the off-duty homicides page--especially Jessie McKinney, George Adams, Edward Gaston, Rita Groshowski, Evelyn Neal, Larry Winstead, and Kim and Keith Crowell. This final section includes a sampling of 19 other cases of claimed self-defense ranging from the clearly justified to the definitely questionable.

Edward Hill (March 19, 1974). Hill, a 31-year-old Black male, was shot and killed by Officer Kenneth Peltier after robbing a bank. Hill entered the bank, asked for a loan application, and returned with a gun and demanded the teller fill a bag with money. The teller gave him $2,000 and tripped the alarm. Chased by police officers outside the bank, Hill ran into a furniture store and grabbed a man as a hostage. Officer Peltier pushed Hill away from the hostage and when HIll reportedly turned the gun towards him, Peltier shot four times at Hill before he could fire. Hill was an accountant with a college degree, and friends and family were shocked to hear the news, calling him a "regular guy." The Homicide Bureau said Hill's motive was being in considerable debt.

Edwin B. Robinson (Oct. 25, 1974). Robinson, a 47-year-old male (race undetermined), was shot and killed by two plainclothes officers, William Morgan and Robert Morris, while he attempted an armed robbery of Lucky Al's Lounge in Northwest Detroit. Robinson and Dexter Van Wicklin, the bar owner, exchanged gunfire but no one was injured even with 14 patrons inside. When the police arrived, Robinson tried to escape with Van Wicklin as a hostage.The two officers killed Robinson with three gunshots after he allegedly refused to drop his weapon and Van Wicklin managed to get free.

Jerome Manning (Oct. 30, 1974). Manning, a 21-year-old Black male, was killed by four narcotics officers in the basement of his home during a drug raid. The officers entered forcibly with a search warrant based on evidence that Manning was a drug dealer. When they entered the basement, Manning allegedly opened fire first with a shotgun. The officers shot Manning in the chest and abdomen, and he died at Detroit General Hospital. No officers were injured, and police arrested four other people in the house on drug charges. They found 125 ounces of marijuana on the premises.

Arthur Williams (Nov. 22, 1974). Williams, a Black male (age unknown), was shot and killed by Tactical Mobile Unit Officer Glenn Monroe Sr. during a stop-and-search operation as Williams was walking down a street on the near West Side. It's not clear from the brief police report reproduced in the newspaper whether the officers had probable cause or reasonable suspicion for the stop. According to police, Monroe fired a shot after Williams pointed a pistol at him and refused orders to drop the weapon. Williams, shot in the face, staggered into the road and was run over by a truck.

Stuart Clay (Nov. 24, 1974). Clay, a 24-year-old Black male, was shot in the head by Officer Fernon Douglas after Clay allegedly robbed a Northwest Detroit home at gunpoint. Police said that Clay disguised himself as a Western Union delivery man and held four individuals at gunpoint, tying them up. Clay fled when officers arrived and allegedly turned and pointed a gun at Douglas after they ordered him to halt. Douglas shot Clay in the head and he died later at the hospital.

Eric Daniels (Dec. 20, 1974). Daniels, a 23-year-old Black male, was shot and killed by Officer Kenneth Peltier after Daniels allegedly shot and killed an officer following an arrest and while in custody. Officers Robert Hogue and Gary Funson arrested Daniels at the Keynote Bar in Northeast Detroit for jumping bail on a theft charge. Both officers missed Daniels's pistol when searching him and once inside the car, Daniels--although handcuffed with his hands behind his back--somehow shot Hogue in the neck, fatally wounding him. Funson jumped out of the car, fired one shot, and called for backup. Tactical Mobile Unit Officers Peltier and Tim Mifares arrived as Eric Daniels allegedly exited the vehicle with Officer Hogue's gun. Those officers said that Daniels--although still handcuffed--shot at them four more times before Peltier shot Daniels in the left abdomen, killing him. It was a violation of police procedure for one of the officers not to be riding in the back of the squad car with the prisoner.

Harley Horrell (Jan. 8, 1975). Horelll, a 70-year-old Black male, was shot and killed by Sgt. Michael Krotche after Horrell allegedly fired his pistol multiple times wildly from a barricaded apartment. Neighbors told the newspapers that Horrell was robbed that day and had become fed up with the frequent robberies as well as the landlord's failure to provide heat or hot water to units at the Alberta apartment building, which primarily housed elderly Black residents. Horrell pulled a gun on resident Betty Bates, telling her that he would kill someone because he was tired of the robberies and poor living conditions. Sixty officers surrounded the building and shut down the nearby Ford Freeway. After Horrell refused to surrender, police released tear gas into the apartment and battered down the door.The standoff ended with Krotche firing a bullet into Horrell's chest after Horrell allegedly "came out firing." Bates said that she had begged the officers not to shoot him, and a Michigan Chronicle writer later noted discontentment among residents of the area that police had seemingly shot Horrell with intent to kill.

Aubon Hutchens (Marc 19, 1975). Hutchens, a 35-year-old white male, was shot and killed by 11th Precinct officers following an alleged burglary at a home in Northeast Detroit. Police said Hutchens and two other men, all from the suburbs of Hazel Park or Royal Oak, committed the crime while on parole. Responding officers chased the suspects and caught two of them. Hutchens then pulled a gun on the arresting officers, disarming and taking them captive. Additional officers arriving at the scene exchanged fire with the suspects, killing Hutchens and injuring one of the other suspects and Officer John Gross Jr., who was being held captive. Commissioner Tannian later fired a 911 call operator for failing to relay to a dispatcher that suspects were armed, and Officer Gross, who was disabled, sued the operator as well as supervisors for negligence.

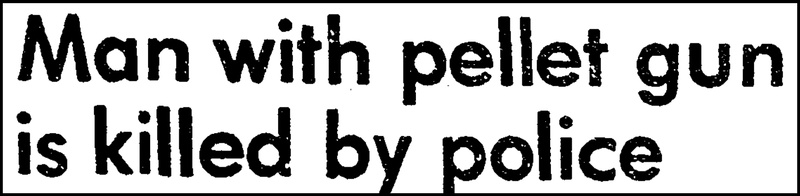

Collie Ray Brim (April 26, 1975). Brim, a 24-year-old male (race undetermined) was shot and killed by Officer Sidney Woryn after he allegedly robbed a Northwest Detroit store, Doll House Wig House. Police said that Brim was running when a woman pointed him out to Woryn and his partner, claiming that Brim had just robbed the store. The officers chased Brim through an alley into a parking lot, and they alleged that he turned around and pointed what turned out to be a pellet gun on them before Woryn shot Brim in the chest, killing him. A police trial board exonerated Woryn, and no charges were filed. Another shooting the next year led the Michigan Chronicle to investigate Woryn, finding that he had at least nine citizen complaints in his three years as an officer, including seven in 1975. A police spokesperson admitted to the newspaper that the number was "unusually high."

Joseph Anthony (Sept. 5, 1975). Anthony, a 50-year-old Black male, was shot and killed by Officer William MacDonald after allegedly pointing a gun at officers following a car chase. MacDonald and Officer Bernard Reed reportedly began pursuing Anthony for reckless driving. Police said that Anthony, who was out on bail, crashed into a parked vehicle and jumped out of the car with a revolver, and attempted to flee on foot. MacDonald gave chase and Anthony allegedly pointed a gun at the officer, who shot Anthony in the head and chest, killing him.

Thomas Hardrick (Sept. 18, 1975). Hardrick, a 29-year-old Black male, was shot and killed by Officer John Winslow on his own porch in a questionable incident. According to the Homicide Bureau, Winslow and his partner saw Hardrick walking down the street with a gun and ordered him to drop it. Hardrick allegedly refused, walked onto the porch, cursed the officers, and pointed the gun at them. Winslow then shot Hardrick in the chest in self-defense. The Michigan Chronicle interviewed an eyewitness and other nearby residents who told a very different story. They said police were responding to reports of a shootout between two East Side gangs and that Hardrick had not encountered the police on the street. Instead, the unnamed female eyewitness said that she and Hardrick were sitting on the porch of the house he shared with his parents and he had a loaded .38 caliber pistol in his possession. The female said when the police approached the house, she yelled “he’s got a gun” and one of them opened fire. In her account, Hardrick was not pointing the gun or threatening the officer when he was killed.

Daniel Keating (Nov. 12, 1975). Kearing, a 34-year-old white male, was shot and killed by Officer Robert LaMore after Keating allegedly threatening the officer with a pellet gun. Keating, who lived in the suburb of Warren, was allegedly threatening patrons with a gun at the Qwicki Bar in Northeast Detroit around 11 pm. Responding officers found the patrons on the ground and Keating hiding in the bathroom. Police said LaMore shot Keating in the chest after Keating pointed the pellet gun at him.

Vincent Polzin (August 1, 1976). Polzin, a 23-year-old white male, was shot and killed by Officer Roger LaMondra after police responded to a false report that a man had shot a child at a Northwest Detroit park. Polzin was apparently in the park with a gun and had fired it but not his anyone. When LaMondra and Officer Gary Teague, his partner, approached Polzin's car for questioning, Polzin shot Teague twice. LaMondra and backup officers then fatally shot Polzin. Teage was wounded but not fatally.