Limited Reform

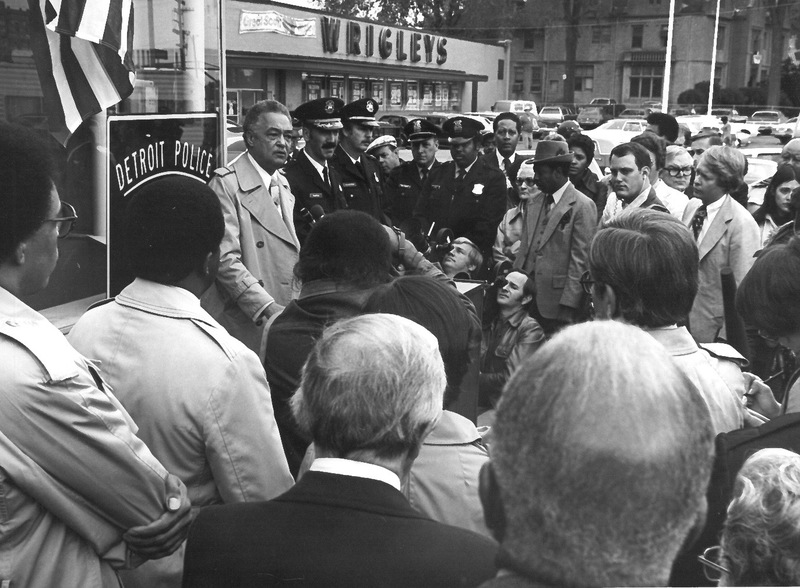

Since the late 1950s, civil rights groups and radical activists have been demanding a civilian review of the Detroit Police Department (DPD). As the department’s violence continued to escalate, as did the demand for a civilian review board. In the 1960s, police violence against civilians was at an all-time high. The Ad-Hoc Action group was one particularly vocal civilian response that outlined their mission to “cop-watch.” The Ad-Hoc Action group formed in the spring of 1969 after the police violently responded to peaceful protestors at Cobo Hall. Their primary observation was the lack of institutional responsibility officers really had to the safety of civilians. Under their current structure, officers essentially had free reign and as an entity, the department was rarely held accountable for their prolific, racist violence. Without any responsibility to the people, in one report the Ad-Hoc Action group labeled Detroit as a piece of the “American Police State.” Arguably, the only solution was to ensure civilians established control over the department. Over the summer of 1969 the Ad-Hoc Action Group, among other activists organized the Citizens’ Police Trial Board Petition campaign. The goal was to amend the new City Charter and “elect 16 civilians, one from each precinct region, to four-year terms on a commission with the power to investigate all allegations of police misconduct in hearings open to the public.”

Notably, Coleman Young, a state senator at the time, worked very closely with the Ad-Hoc Action Group on this campaign for a civilian review board. However, in 1973 now Mayor, Coleman Young did not pursue a civilian review board with the same ferocity. Rather than an elected and autonomous civilian review structure, he agreed upon a mayor-appointed Board of Police Commissioners. The establishment of the Board of Police Commissioners, while a reform, amounted to be a rather limited and ineffective entity. The Detroit Police Department continued to be corrupt and violent. Officers were not “held accountable” particularly considering “accountability” was defined under the same punitive carceral structure that fails to change behavior. Black civilians continued to be categorized as criminals and violently targeted for their existence. The establishment of the Board of Police Commissioners felt like a broken promise from a once ardent activist.

Launching “A New Era”

1974 had the hope of a new start for Detroit. In the Free Press as well as the Michigan Chronicle, 1973 was framed as the year of crisis and 1974 promised to change all of that. The people had a new mayor and a new city charter. It was a new beginning for Detroit. The City Charter was of particular excitement for the city. A new charter is similar to a constitution in that it is more difficult to repeal, and the city had not had a new charter since 1918. It was hoped to be the "key" to leaving hostile community-police relations in the past. The city elected the Detroit Charter Revision Commission on November 3, 1970, with the sole task of drafting the new city charter. The commission was particularly focused on addressing issues of police-community relations and the demand to restructure how the city handled civilian complaints and officer discipline.

Board of Police Commissioners v Civilian Review Board

A civilian review board was being demanded by the community through letters to the administration before Young came into office. Young championed community involvement in his reform policies and he believed that civilian influence over policing would serve as a solution to police misconduct. it seemed that this would finally reach fruition. While the decision can often be conflated with Young's leadership, it is important to note that it was ultimately the decision of the voters and the City Charter Commission.

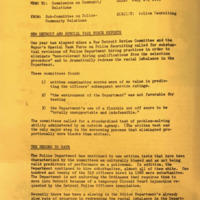

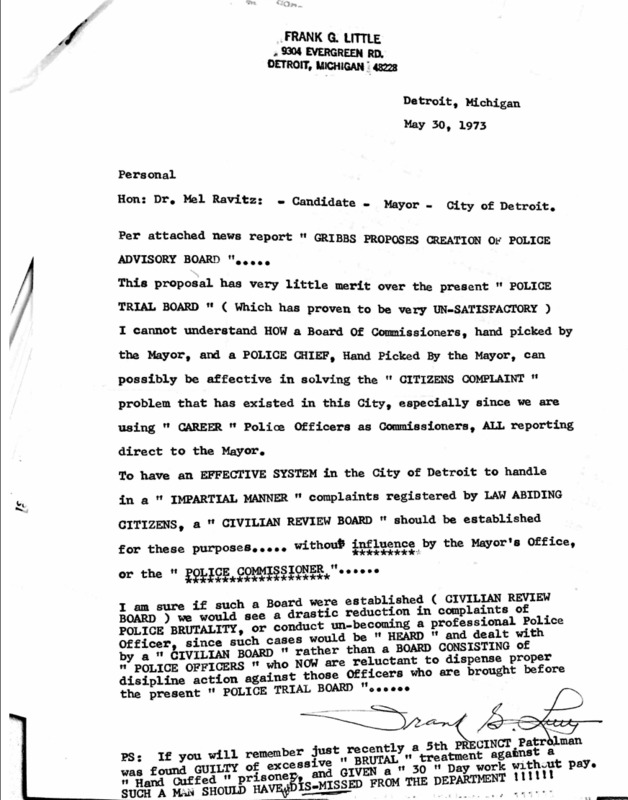

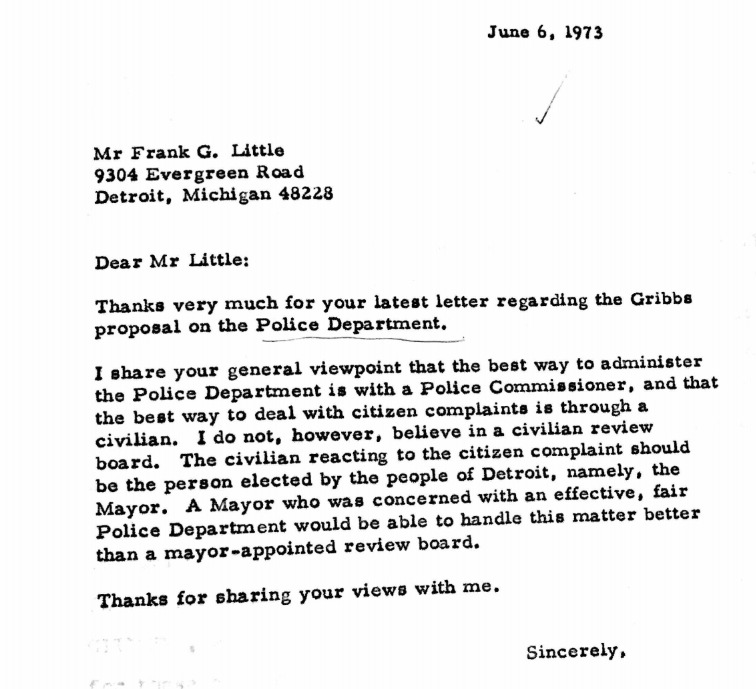

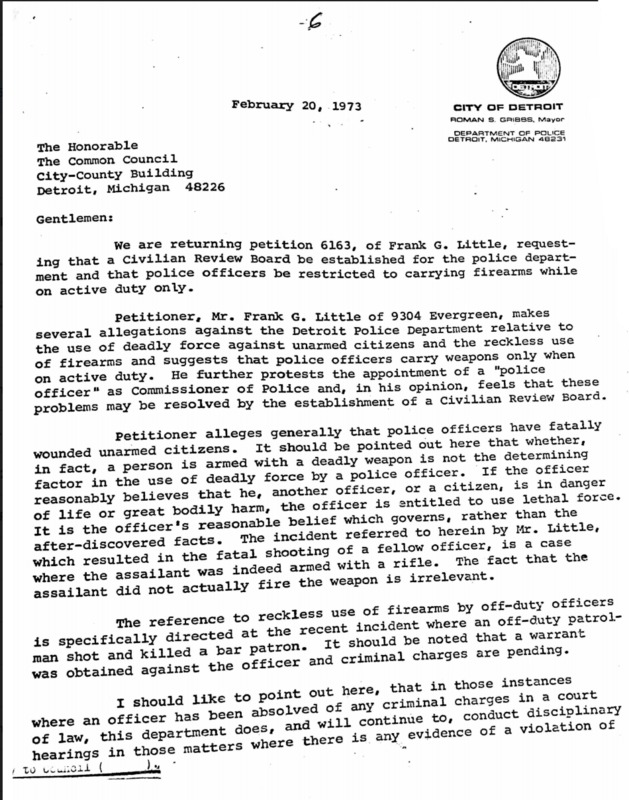

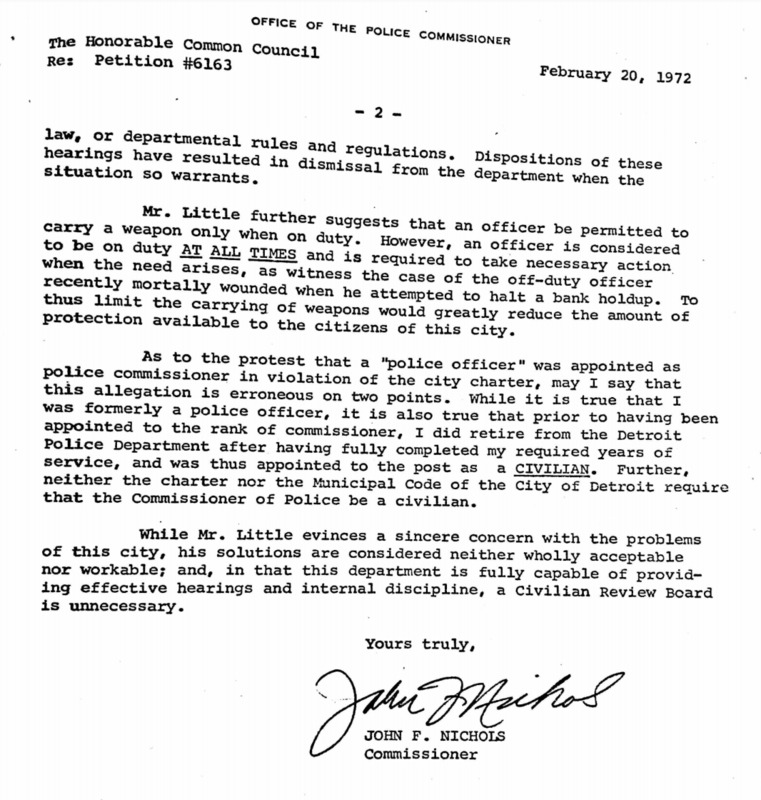

As displayed to the left, citizens were involved and vocal about the decisions being made in the city. There was a formal complaint process, later restructured under Young, that received active participation. Frank Little’s complaint was directly addressing the widespread frustration regarding the lack of civil authority in the police department. Little wrote to Mel Ravitz, a progressive politician that marketed himself as a community advocate, who, in 1973 was President of the city council and running for Mayor. Ravitz’s career was framed around being a voice for low-income Detroit, it made sense for Mr. Little to turn to Dr. Ravitz with his frustrations. Little apparently attached a news report to his complaint, detailing the plan that current Mayor Roman Gribbs proposed on creating a “Police Advisory Board” in the upcoming city charter. The Board’s duties would include handling police misconduct and the members, as proposed by Gribbs, would be appointed by the Mayor.

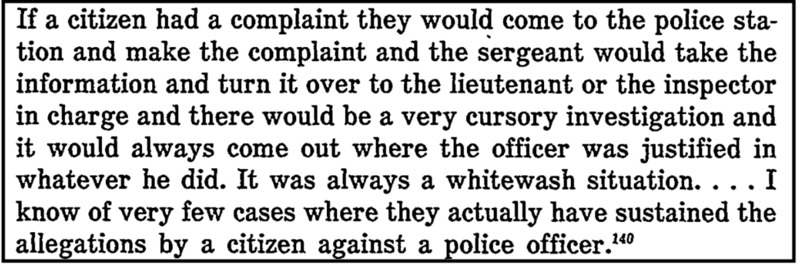

According to Little, at the time, the city had a Police Trial Board, which served essentially the same purpose. Little wholeheartedly believed that to effectively discipline the officers, citizens needed to be in control of their sentences. Little was unsatisfied with the current board and frustrated with the lack of change. He states, “I cannot understand HOW a Board of Commissioners, hand-picked but eh Mayor, and a police chief, handpicked by the Mayor can possibly be effective in solving “citizens complain” problem that has existed in this city, especially since we are using career police officers as commissioners, all reporting directly to the mayor.” Little continues in saying that an effective system, to handle what should be impartial as the complaint system, should be registered by law-abiding citizens, a “civilian review board” should be established without influence from the mayor's office or a police commissioner. He was frustrated with the continued lack of sufficient punishment for officers found guilty of using excessive and deadly force on civilians. The implicit bias of the officers worked to continuously protect each other over protecting the citizens of Detroit. Ike McKinnon, an officer since 1965 who went on to be the Chief of the DPD in 1993, called the phenomenon “the blue curtain.” [insert audio explaining what this is] Officers will not testify against other officers regardless of their wrongdoing, ranging from corruption to killing civilians. Little is echoing the activists in the community that continuously state civilians are the only ones who will see to it that officers are properly held responsible. He is concerned that anyone with any affiliation to the DPD, officer or not, will fail to pursue genuine justice.

“If the law is to be honored, it must first be honored by those who enforce it” — Cannons of Police Ethics, Article IV

Little posits a “Civilian Review Board,” a board consisting of solely civilians that will hear cases against officers and be in charge of decisions. Civilian Review Boards have been demanded in large cities across the country for the reputation that civilians will have a more direct role in disciplining officers and handling complaints. However, Edward Littlejohn as cited in his 1981 study, believed the Board of Police Commissioners would actually be a step forward from the Civilian Review Board model. Civilian Review Boards in practice have historically lacked the financial and structural support to enact legitimate change while they continuously battle the resistance of the white officer unions. In order to build his argument, Littlejohn uses Philadelphia and New York as case studies which each created a civilian review board equivalent in 1957 and 1966 respectively. In Philadelphia, the civilian review board was created by a liberal mayor as an executive order. As such, it could be easily revoked and altered. They also lacked funding. To compare, Detroit's 1974 Board of Police Commissioners had a budget of $211K while Philadelphia's civilian review board had a mere $17K.

They were understaffed and lacked formal guidelines and therefore unable to effectively manage complaints or establish the power to discipline officers. New York’s civilian review board equivalent was an advisory council and adopted from their previous model. They had structural precedence but were confronted with a massive anti-civilian involvement campaign that was launched by their white police union, the Patrolmen Benevolent Association (PBA). The PBA spent almost their entire budget on the campaign, opposed by organizations like the ACLU. When it came time for the civilian vote, the white population made the decision to disband the civilian review board. Even white liberal voters sided with the PBA due to the primary message of their campaign: direct civilian involvement would remove cops from duty and prevent the department from effectively fighting crime. A similar message would be spread by John Nichols, Detroit’s Police Chief at the time in his anti- civilian involvement crusade. The Commission was likely aware of both of these failures and recognized the importance of sufficient structural guidelines and financial backing that had to be balanced with the concerns of police autonomy. Littlejohn recognized the importance of civilian involvement in the police department and complaint procedures, however, he balanced this with an assertion that civilian review boards in practice serve as a palliative that lacks the internal hegemony to enact legitimate change. Along the same thread, he posited that while imperfect, the Board of Police Commissioners that Detroit created is a more promising and long term model to respond to concerns over biased investigations of police misconduct.

The City's Decision

On July 1st of 1974, the new New City Charter establishes a Board of Police Commissioners. The Commission had been working on its guidelines since the Commission’s inception in 1970. From 1970-1974 the issue of restructuring the department and revamping the methods for handling civilian complaints were heavily contested. The Commission held several town hearings which were widely attended. Members from the DPOA, Northwest Council of Homeowners Association and the Community Homeowners Association were among the voices of anti-civilian involvement while civil rights organizations and civilians were adamant about establishing control in the DPD. John Nichols, the police chief at the time spearheaded a media campaign that directly targeted any civilian involvement. The Detroit News and the Detroit Free Press had a close relationship to the department and primarily published articles on the failures of civilian reviews in other cities, insinuating that any civilian-centered model would result in a similar failure. [for more on the media’s relationship with the DPD click here]. They were trying to fear monger citizens into believing that civilian input would lead to an inefficient department that could not effectively fight the crime that became analogous to Detroit, i.e. Murder City, USA. However, such attempts were futile considering the shifting demographics. The African American population had more power than ever before and the current department was already not protecting them. Any attempt to create the obstruction narrative as a legitimate deterrent for civilian involvement was immediately rebuked.

As such, by 1973, when John Nichols was also running for mayor, some degree of civilian involvement became inevitable. The goal shifted to reducing the impact of that involvement. Nichols came to support a five-member policy making body that had some power to deal with police misconduct. Prior to the election, in 1970, Coleman Young was documented working to rally support for a civilian review board. But even Young by the time of his election seemed willing to compromise, particularly because according to the charter, the mayor appoints the members of the Board. This was a contested policy by both the liberal prior complainant Frank Little and the conservative DPOA. That said, Mayor Young appointed Edward Littlejohn, Susan Mills-Peek, Douglas Fraser, Rev. Charles Butler, and Alexander Ritchie. The appointees were meant to represent the myriad of civilian interests including education, civil rights, the clergy, labor, and public interest. Their first meeting was on July 22, 1974, convened by Mayor Young. The focus of the meeting was affirmative action, diving right into controversy. The main weakness of the Board, from Littlejohn’s perspective, was the tenuous relationship between the Board and the Chief of Police, Tannian. The charter was drafted to change the fact that police controlled the investigations of citizen complaints and Tannian adamantly against that proposal. The Board acquiesced to the Chief due to their dependence on the Chief and his staff for access to citizen complaints. Without an independent investigative process, it was seemingly impossible for the Board to determine the diligence of the departmental disciplinary system. The excerpt selected is a quote extracted from Littlejohn's Law Review which highlights the lack of officer discipline, particularly when they are largely in charge of the investigative process.

The Board of Police Commissioners was an attempt to reach a middle ground between direct civilian involvement and maintaining levels of police autonomy. Compromise can be especially difficult to reach when the issue is deeply polarized and emotionally tied. The Board of Police Commissioners began without sufficient staff or procedures to guide it, but it had a strong foundation in the charter and significant financial backing. As outlined by Detroit’s administrative site, the Board has complete authority over citizen complaints, has the power to appoint fact finders, subpoena witnesses, administer oaths, take testimony, and require the production of evidence. They also appoint a civilian as the Police Personnel which is intended to increase civilian control over hiring practices and written, oral, and medical examinations within the department. The board must also approve all promotions made by the chief which was particularly important in the early 70s regarding affirmative action and the consequent debates around promotional practices. White officers with seniority felt neglected as less experienced African American officers and women were promoted before them. However, African Americans and women were institutionally prevented from reaching the same levels of seniority and this was largely ignored by the white male officers complaining. [for more on affirmative action click here]

Thus, while the civilian review board did not reach fruition, Coleman Young remained determined to create a system of community-involved policing. The method he elected became known as the “ministration.” Another tactic was the scooters. [For more on community policing efforts click here]. Furthermore, one of the major tasks of the Board of Police Commissioners was restructuring the complaint system. In 1975 the board-created Professional Standards Section processed 3,457 complaints, a 200% increase over the cumulative total of 1,733 complaints reported during the preceding nine year period. [For more on the complaint system click here]. With a new mayor, and a new charter, the people felt that they had some power, and with that belief, they worked to exercise it. It would seem, the true key to community participation in their own administration is to generate the belief that their efforts will enact some change. To sustain that involvement, there must be follow-through, and while the initial uptick in complaints seems promising, after some disappointment in the reform, the participation waned. Coleman Young’s election and determination to reform was perceived as genuine and excited his African American constituency, but it takes more than a single figure to change a system entrenched in injustice. The acquiescence to the creation of a Board of Police Commissioners with limited legitimate independent authority over a civilian review board serves as a microcosmic example of the continued compromise the once-radical Coleman Young must make as mayor. His focus will continue to shift throughout his first term, but already in the first year, he has provided a glimpse of the more moderate tone his administration will follow.

Add here from the 1980 feature on the BPC link

Sources for this page

Edward J. Littlejohn, "The Civilian Police Commission: A Deterrent of Police

Misconduct," University of Detroit Journal of Urban Law 59, no. 1 (Fall 1981): 5-62

Young, Coleman, and Lonnie Wheeler. Hardstuff: The Autobiography of Mayor Coleman Young. Viking Books, 1994.

Letter to Dr. Mel Ravitz from Frank Little, May 30, 1973, Correspondence on Police Board of Commissioners, Mel Ravitz Papers Folder 6, Box 50, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Letter to Frank Little from Dr. Mel Ravitz, June 6, 1973, Correspondence on Police Board of Commissioners, Mel Ravitz Papers Folder 6, Box 50, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Memo to City Council from Mayor Gribbs, February 20, 1973, Correspondence on Police Board of Commissioners, Mel Ravitz Papers Folder 6, Box 50, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Gail Starr, "Police and Civilian Review" sent to Police Community Relations Committee by Joseph Schore, Director, August 25, 1969, Correspondence on Police Board of Commissioners, Mel Ravitz Papers Folder 6, Box 50, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University