I. Broken Promises (1974-77)

Note: section 1 is still in development and should not be cited or quoted or reproduced without contacting mlassite@umich.edu first. The data on police homicides in this section is complete.

1974 marks an important shift in the mayoral leadership and racial politics of Detroit. The city was going through stark demographic shifts due to the increase of “White Flight” following the 1967 uprising (link). Whites were moving away from downtown into new suburban developments, which African Americans were barred from, effectively shifting the demographics of the city towards a higher percentage of African Americans. In 1970, the population was 55% white and 44% African American. By 1980 it completely flipped with the white population down to 34% while African Americans now made up 63% of the city.

The map below illustrates the demographic shift from 1970-1980. The African American population is represented in shades of blue, and the white population is in orange.

Use the sliding bar to swipe back and forth between the data

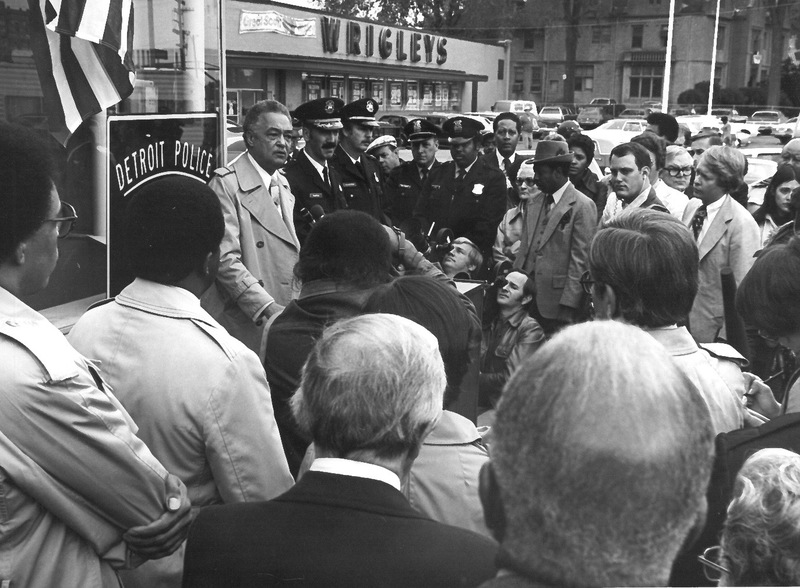

A New Detroit

Nationally, Detroit was known as “Murder City, USA” and everyone, especially Mayor Young, was eager to change that image. With a new mayor and a new city charter, 1974 had the potential to be a fresh start. As one of the first steps into the proposed new era, Coleman Young abolished STRESS, a plainclothes operation that resulted in unprecedented civilian deaths by police. Young promised an increase in police accountability and championed a community-involved system of policing. While Mayor Young was successful in the implementation of several of his reforms, especially affirmative action to diversify the DPD, the growing strength of the white police union, the DPOA continually challenged his efforts. They were vocal antagonists regarding affirmative action, arguing the reforms were prejudice against white officers with seniority. They fought Young on nearly every attempt to reform.

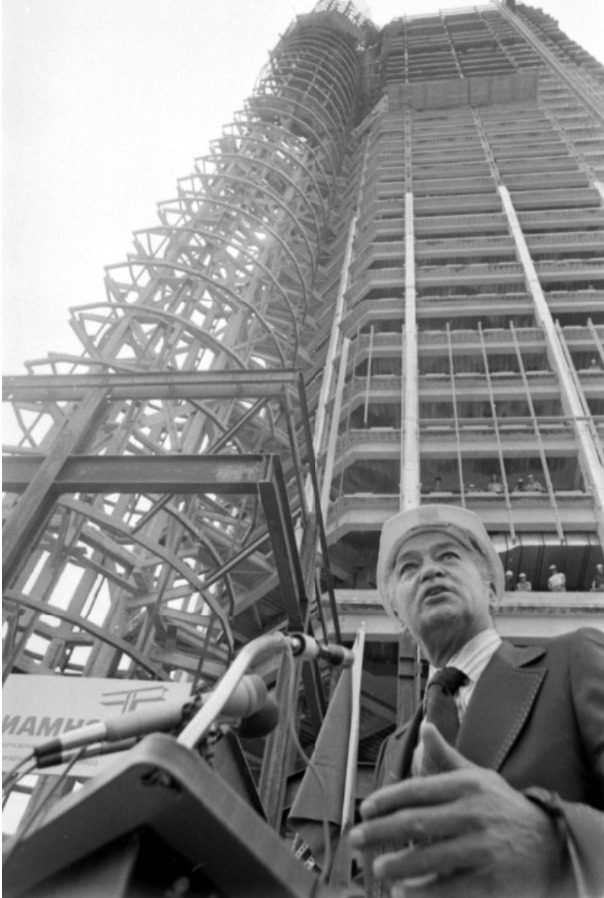

In addition to reforming the DPD, Mayor Young focused his efforts on development and fostered close partnerships with white power brokers such as Henry Ford II. The continuously high crime rate and terrible national reputation, particularly the “Murder City” label, proved to be obstacles in the rebranding process. The goal was to develop downtown to attract positive press and bring business back into Detroit. But, white suburbanites feared the city, and were reluctant to spend the day downtown. This gave rise to “anticrime architecture,” creating structures that allowed patrons to park and enter the building without any interaction with the city itself. A crime-ridden city surrounded by the pristine suburbs reflected the national perception, thus anti-crime architecture became a national trend. The Renaissance Center was Detroit’s iteration and source of pride.

The Push for Community Policing

Mayor Young’s police reforms were highly reflective of his “law and order, with justice” platform. Foremost, the Mayor sought to alter the demographics of the Detroit Police Department to reflect that of the city’s population. Both affirmative action hiring practices by race and gender, and residency requirements for police officers, successfully shifted the DPD’s demographics. Further, Mayor Young pressed for reforms that would simultaneously control crime and alleviate racial antipathy within the DPD. He argued that the solution was to fortify the relationship between the community and the police department. The majority of Young’s campaign vow that “The People and the Police Will Work Together,” (X), ultimately translated into community policing, an approach to law enforcement trending in cities nationwide. This approach is valued as a means of crime control and improve community perceptions of police. Thus, the establishment of small, satellite police stations, dubbed mini-stations, throughout Detroit between 1974-1977 became the Mayor’s primary innovation in community policing. On the surface, the intention of the mini-station program was to promote regular contact between police officers and community members. However, it may be argued that the operation of these mini-stations, particularly in neighborhoods of low SES, did little to improve the community-police relationships.

The drastic increase in unemployment coupled with economic shifts in the 1970s significantly altered the social structures among young people in many of Detroit’s communities. This empowered the formation of informal work groups comprised primarily of unemployed, African American youths became fixtures of the informal economy (Stauch, 13). These groups have been more familiarly labeled as gangs. The cultivation of these groups in the 1970s rekindled the public’s fears of gang violence. The involvement of youths challenged the previously understood perception of gangs--having traditionally been understood as organized and territorial. Particular watershed events of the mid-1970s, including the Livernois 5 and Cobo Hall incidents, exacerbated fears of gang violence perpetrated by youths.

The aftermath of such events enabled the Detroit Police to justify a punitive crackdown of these “gang” groups--consisting of young, African American men. The sensationalizing of these events oriented the public majority, consisting of both African American communities and business elites, to be in favor of such anti-crime initiatives.

The aftermath of such events disrupted equilibrium in Young’s vision for social utopia (wording?). Thus, throughout the mid-1970s, Mayor Young and the Detroit Police Department ordered a crackdown on youth in the city. This ignited a major shift in the emphasis on punitive rather than rehabilitative measures for youth. Policies enacted during this shift reflected only the hegemonic vision of law and order, and as a consequence, criminalized essentially every young African American individual in the city.

Police in Schools

A powerful manifestation of racially prejudiced discretionary policing was the criminalization of low-income black students from a young age in public schools. Schools exist in a bizarre jurisdictional gray area because of the complex way that student conduct is governed both by internal disciplinary guidelines and procedures and simultaneously by local, state, and federal law. The inner workings of this perplexing system become even more murky in instances when school districts decide to allow police into their schools—as the DPSCD did in 1975 when its board voted to allow armed police officers past the schoolhouse gates. This decision was praised and condemned by people across political and racial divides. Even though the black citizenry was being criminalized by these policies they were willing to give the newly elected mayor some leeway as they trusted him to have their best interests at heart. These policies are part of the early roots of the school to prison pipeline we see today.

Efforts for Police Accountability

In an effort to increase police accountability, the New City Charter created the Board of Police Commissioners and established a new manual for the Professional Standards Section which worked to process citizen complaints. A civilian review board was being demanded by the community through letters to the administration before Young came into office. Young championed community involvement in his reform policies and he believed that civilian influence over policing would serve as a solution to police misconduct. It seemed as though the civilian board would finally reach fruition. However, after some debate, the mayor-appointed, five-member Board of Police Commissioners was established instead. While the decision can often be conflated with Young's leadership, it is important to note that it was ultimately the decision of the voters and the City Charter Commission.

The City Charter Commission also worked to restructure the procedure for handling citizens’ complaints. In the 1918 charter, the system was reduced to 30 words. The New City Charter sought to delineate a more exhaustive procedure in hopes the structure would increase police accountability. “The Blue Line” or “Blue Curtain” refers to the camaraderie between officers that results in police protecting each other when they cause harm[link]. Under the new system, police were still largely in charge of monitoring and disciplining themselves, and as such the vast majority of complaints resulted in either an unfounded claim or proper procedure. Only one officer each year was dismissed despite that in 1974 alone, officers killed 30 civilians and injured over 900 that we know of. The Board of Police Commissioners held the power to discipline officers, there were some efforts for more civilian review involvement by 1976 [link].

The efficacy of the New Manual was debated but the department did see a huge surge in civilian complaints in both 1974-1975 which alludes to increased trust in the system. Unfortunately, the increase in complaints and subsequent investigations did not lend to a changed department. It is impossible to file and investigate away all “bad apple” cops. What was clear to activists in the 70s has come into the collective conscience today: the entire policing and criminal justice apparatus is violent and destructive and reform will never be a sufficient response.

NEED TO PREVIEW: corruption of DPD in drug markets as a reform target too, and the flooding of money for drug task forces from the 1970 drug control law passed by Congress, new police chief

Detroit Police Department Misconduct and Archival Silences

The data that we collected that tracks police misconduct and brutality against the people of Detroit is largely based on complaints filed by citizens to the mayor’s office. By examining the complaint process we can assess its efficacy and identify the silences it created. During this time period the city required people to fill out these complaint forms at police precincts, often in front of officers they sought to complain about. This dynamic likely made people uncomfortable and thus altered the nature of their complaints. As time progressed, the records show that people lost faith in the process as many fewer complaints were lodged. In 1974—Coleman Young’s first year as mayor—there are dozens of folders, each filled with hundreds of complaints against police officers. For the years after, there are only a couple of folders. This could indicate that the police department was reformed so effectively that there were many fewer instances of misconduct that warranted complaints. However, given the drastic decline, this seems unlikely. Another possibility is that the newly created Board of Police Commissioners began to receive a bulk of the complaints as opposed to the mayor’s office. Regardless, the drop is so abrupt and dramatic that it is fair to say there appeared to be more optimism about reform when Young was first elected. It is also important to note that those accustomed to and anticipating police harassment are less likely to complain. The absence of this metadata is reflected in the maps as well, illustrated as entire sections of the city free from incidents. It is not that these areas evaded the pervasive brutality by officers, but rather, lack formal documentation.

The Detroit Free Press and Detroit News articles about instances of police misconduct and homicides of civilians are often times very one-sided. The reporters’ main source for their work was the police department itself. Many reporters maintained close personal relationships with police officers. In exchange for information, the reporters would provide favorable coverage. It was not worth it to them to thoroughly investigate each case and provide a sophisticated, nuanced narrative that might put an officer in a bad light as that might have meant losing a source. For several metadata incidents, the only sources we have are the newspapers. When there was a court case, we often have much more information from witnesses and a more critical analysis of the officer’s actions. Unfortunately, this detail is often lost. Furthermore, there are many stories left untold. Either the documents were discarded, or the incident went unreported. As previously mentioned, we have much less information on police brutality and misconduct in the areas with the lowest income. Likely, the newspapers made deliberate decisions about which stories to tell and which to ignore.

Sources for this page:

NCJRS: The Administration of Criminal Justice: Perspective from Black America

Stauch Jr, Michael. "Wildcat of the Streets: Race, Class and the Punitive Turn in 1970s Detroit." PhD diss., Duke University, 2015.