Police Violence + Fatal Force

This section examines fatal shootings and patterns of brutality and misconduct by officers in the Detroit Police Department between 1974 and 1977, Coleman Young's first term in office and the era that launched the mayor's "community policing" policies and reforms. This landing page covers DPD policies for the "use of firearms" by police officers and the internal investigation procedures when police fired weapons and deployed fatal force--including revisions implemented and reforms resisted by Commissioner Phillip Tannian and his successor, Commissioner William Hart. The following pages examine on-duty and off-duty police homicides between 1974-1977, as well as citizen complaints and high-profile incidents of brutality and misconduct.

Use of Firearms Policies

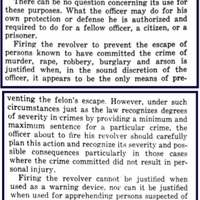

The Detroit Police Department modified its use-of-firearms policies and also changed the top-down messaging around police shootings of civilians in the mid-1970s. When Coleman Young took office in 1974, the DPD's "Use of Firearms in Police Action" policy remained unchanged since the revisions enacted immediately after the 1967 Uprising, which located the determination to use fatal force in the "sound discretion of the officer" (at right). This was part of a national get-tough movement to anchor legal authority for fatal force in the individual discretion of the officer on the street, in order to insulate police violence from administrative reviews and criminal proceedings in an era of civil rights and anti-police brutality activism.

The DPD's prior use-of-firearms policy in operation from 1962-1967 had restricted deadly force to "extreme cases" and also discouraged firing on fleeing suspects. The 1967 revisions deliberately loosened the regulations and added burglary, often a low-level property crime, to the list of felonies that justified killing a suspect who sought to evade apprehension. This liberalized policy, openly justified as a deterrent for Black male "street crime," helped usher in an extraordinary surge in police violence and fatal-force incidents in Detroit during the late 1960s and early 1970s.

The DPD maintained the same use-of-firearms policy during the short tenure of Commissioner Phillip Tannian, who served from 1974 through mid-1976. The DPD under Tannian did take some steps to reduce police-involved fatalities, including conducting an internal review to identify the small subset of officers who repeatedly fired their weapons. The DPD refused to release these names publicly but instead required the officers to undergo retraining, psychiatric counseling, and in a few cases reassigned them to office jobs.

Commissioner Tannian did update other DPD policies, including the Board of Review process to investigate fatal shootings (below gallery, left). Tannian also established a Special Assignments Squad in September 1975 as a dedicated unit to investigate police shootings of civilians and civilian shootings of officers. [MORE ON TANNIAN] Yet the number of fatal DPD shootings remained essentially unchanged between the revanchist STRESS era of the early 1970s and the first two years of the Young administration, during 1974-1975. Incidents from these two years are analyzed in more detail on the following page.

Commissioner Hart's 1977 Policy Revision

William Hart, the first Black police chief in Detroit's history, replaced Tannian in September 1976 and revised the use-of-firearms policy in January 1977 (at right). The updated policy began with a much more forceful preamble instructing police officers that "the use of firearms shall be confined to situations of strong and compelling need" and that they had a legal responsibility to "use only the minimum degree of force necessary to effect an arrest." The preamble also reminded officers that "the maximum sentence imposed by our court system would result in neither death nor injury." Additionally, Hart's policy revision:

- Maintained the longstanding provision that officers could "use firearms to protect themselves and others from serious bodily harm or death"

- Removed the language locating the authority to fire on a fleeing felon in the officer's "sound discretion" (this had led to the city of Detroit losing many civil lawsuits even when the Homide Bureau and prosecutor found shootings to be "justified") [ADD LINK OR MOVE]

- Restored the pre-1967 language that officers could not fire on fleeing suspects based on "mere suspicion" and added that they "must know, as a virtual certainty, that the person committed an offense for which the use of deadly force is permissible"

- Listed the same class 1 felony offenses as justifiable to use firearms to prevent escape (murder, rape, arson, robbery, serious assault) but defined burglary more precisely as "felonious breaking and entering" (in the early 1970s, police often fired on suspects, including juveniles, for low-level burglary crimes)

- Elaborated that officers had to have "exhausted all other reasonable means of effecting the arrest" before opening fire

- Informed officers that they would face "criminal liability" if they used fatal force based on "suspicion only," in violation of the department policy and state law

- Banned firing warning shots and discouraged shooting from a moving vehicle except "in cases of extreme necessity"--because of the risk of harming innocent bystanders

- Included additional sections on regulations for carrying department-issue and personally owned firearms; firearms safety and training; and procedures for filing "shots fired" reports. These can be found in the full 1977 policy in the gallery at the bottom of the page (second from left).

Michigan Supreme Court Legal Standard

The state of Michigan did not directly regulate police use of fatal force before or during the 1970s by statute, meaning that courts developed the prevailing doctrine through common law and a series of rulings. Officers had the right to self-defense or the defense of others, just like non-officers, but they also had a specific positive legal right to shoot in the so-called "fleeing felon" scenario.

Case law from the Michigan Supreme Court during the 1970s gave police departments and individual officers significant discretion to use force against suspects in the process of making an arrest. In Delude v. Raasakka (1974), a case from Flint alleging police brutality, the Michigan Supreme Court held that "the police have the right to use that force reasonable under the circumstances to effect an arrest" and "the right to use reasonable force in case of resistance." This included "the right to protect himself and others in effecting an arrest."

The Delude case did not involve fatal force, a theme directly addressed by the Michigan Supreme Court in People v. Doss (1979). That case addressed an appeal from a Detroit police officer charged with manslaughter for shooting an alleged burglary suspect (George Adams in 1976, profiled on the next page). In Doss, the Michigan Supreme Court permitted the trial of the officer to go forward but also elaborated the legal standard of "reasonable force," citing the American Jurisprudence handbook:

The Michigan Supreme Court further held that "unlike the private citizen a police officer, by the necessity of his duties, is not required to retreat before a display of force by his adversary." But as with private citizens, the officer "who claims self-defense must have reasonably believed himself to have been in great danger and that his response was necessary to save himself therefrom." This reasonableness standard continued to invest significant weight in the discretionary decision-making process of the police officer and the officer's own reports and testimony about the state of mind.

In a major 1981 report, the Michigan Civil Rights Commission criticized the state legislature for failing to enact a statute to govern police use of deadly force and specifically called for a law to prohibit firing at a fleeing felon. The MCCR also argued that legislation should restrict police authorization to use deadly force only to situations where there was a "reasonable belief that there is an immediate threat" to the life of the officer or another person. The MCCR's 1981 report is covered in depth in Section II of this website exhibit.

DPD Reforms Not Taken in the 1970s

During the 1970s, the national debate over whether and how to constrain police use of fatal force focused on three legal and policy questions in particular: legislative prohibitions on firing at "fleeing felons" who posed no direct threat; the propriety of shooting at juvenile suspects; and the problem of homicides by off-duty police officers. The state of Michigan and the Detroit Police Department did not enact any of these proposed reforms, although the proportion of DPD shootings of "fleeing felons" and of juveniles did begin to decline by the second half of the 1970s. Homicides by off-duty officers, many of them questionable at best, remained a persistent problem.

"Fleeing Felons." Chief Hart's policy revision did not seek to restrict fatal force as aggressively as some other big-city police departments did during the same era. The 1977 policy revision by the Los Angeles Police Department, for example, told officers to act with "a reverence for human life" and explicitly stated that "the use of deadly force is not justified merely to protect property interests." The LAPD also adopted the more restrictive standard that officers should not shoot at fleeing felons except to prevent future harm--"when there is a substantial risk that the person whose arrest is sought will cause death or serious bodily injury to others if apprehension is delayed."

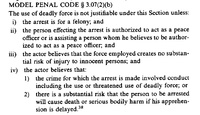

Police use-of-force can be constrained, or left unchecked, by state legislatures as well as by internal department policies. Since 1962, the American Law Institute had recommended that states enact a Model Penal Code restricting the use of deadly force by law enforcement in the "fleeing felon" scenario to cases where the crime known to be committed by the suspect involved the use or threat of fatal force. This would have eliminated police discretion to shoot at suspects for burglary and robbery, even at risk of their escape. The Model Penal Code also held that police should not fire on fleeing felons unless "there is substantial risk that the person to be arrested will cause death or serious bodily harm if his apprehension is delayed" (the language adopted by the LAPD in 1977). This meant that the officer should have to believe that fatal force would prevent death or serious injury in the future, not just that the suspect had committed such crimes before the pursuit began.

Michigan, like most states, did not adopt the Model Penal Code and continued to permit fatal force against even nonviolent property crime suspects under the common-law standard. Edward Littlejohn, a professor at Wayne State and former member of the Detroit Board of Police Commissioners, criticized this inaction in a 1984 law review article that strongly argued for the necessity of external legislative controls on police discretion to use fatal force in situations that did not directly involve self-defense or the defense of the lives of others. Littlejohn concluded that "there is no rational justification for authorizing a police officer to execute a citizen in the streets for an alleged offense which, if affirmed by a trial, could result in a probationary sentence."

In 1984, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Tennessee v. Garner that state laws authorizing police to use deadly force against fleeing and unarmed suspects were unconstitutional. This decision came after decades of civil rights protests in Detroit against the DPD's policy authorizing the use of fatal force in this scenario, especially high-profile incidents involving juveniles. The saga of the Model Penal Code makes clear that the failure to prohibit this ultimately unconstitutional practice rested with Michigan state lawmakers as well as the DPD and elected officials in Detroit.

Juveniles. A few police departments profiled in the Police Foundation study adopted specific policies in the 1970s to prohibit shooting at juveniles except in self-defense. The Police Foundation reported that "most" of the police officers that researchers interviewed in Detroit "feel that they are not to shoot at fleeing juvenile felons," but the DPD's use-of-firearms policy did not address the issue. The Police Foundation recommended, however, that a juvenile exemption would not be needed if use-of-firearms policies restricted the "fleeing felon" scenario to actual dangerous threats. In effect, the report stated that rather than distinguish juveniles and adults, no suspects seeking to escape lower-level crimes such as larceny or burglary should be shot if they did not pose a direct threat.

Off-Duty Police Violence. Off-duty police officers were responsible for a significant percentage of DPD homicides during the 1970s--almost one-fourth of the total, according to our project's research findings. This pattern aligns with the data reported in a major study by the Police Foundation, Police Use of Deadly Force (1977), that off-duty officers committed 22 percent of DPD shootings (fatal and non-fatal combined) during 1974 and the second half of 1973. This was the highest proportion among the cities covered in the report.

The DPD, like most law enforcement agencies, required its officers to carry their revolvers when off-duty, on the presumption that they should always be ready to spring into action and fight crime. Although the policy was longstanding, DPD officials in the Coleman Young era justified armed off-duty officers as an extension of the community policing philosophy, so that they would always be ready to protect law-abiding citizens from criminal threats. The only restriction, in addition to those enumerated above, was when off-duty officers were participating in a public march or demonstration--a response to an incident when off-duty white officers assaulted a Black police officer at a 1975 protest against Coleman Young's affirmative action policies. Many police officers also carried higher-caliber personal firearms when off-duty (and when on-duty), as permitted and regulated by the DPD's use of firearms policy.

Some American police departments during the 1970s began to adopt policies that discouraged or forbade off-duty officers from carrying firearms when drinking alcohol. The Detroit Police Department did not take steps to address this issue, even though many of its off-duty officer incidents happened at bars or otherwise involved alcohol-fueled personal disputes. In fact, the DPD did not prohibit officers who were drinking alcohol or even inebriated from carrying and using their department-issued or personal firearms until forced to do so in 2005 under a federal consent decree.

The Police Foundation's 1977 report on patterns of deadly force warned law enforcement agencies of the problems being caused by armed off-duty officers considered to be crime-fighters even when not in uniform. The report (excerpt at right) acknowledged that armed off-duty officers might be able to prevent or arrest perpetrators of violent crime. But "if, on the other hand, they are making insignificant numbers of quality arrests but constantly embroiling the department in controversial shootings, then the price being paid . . . may be too high."

The Police Foundation specifically flagged patterns (based on national data) of "shootings that grow out of private disputes, not related to duty, often fueled by the consumption of alcohol," as well as officers who used their weapons in domestic violence incidents. All of these scenarios also arose in Detroit, as revealed in the detailed case studies on the off-duty police fatalities page for 1974-1977 and in the subsequent sections of this website. The DPD did not heed the Police Foundation's recommendation that "a set of rules limiting off-duty action to situations involving serious crimes or a danger to life might reduce the number of shootings by off-duty personnel at little cost."

Internal Investigation Procedures

Unlike some police departments during the 1970s, the DPD did not investigate fatal shootings by its officers through a centralized internal affairs unit, a process designed (in theory) to reduce conflicts of interest and assure a more neutral outcome. Instead the DPD continued to follow its longstanding practice of "chain-of-command investigations" where the immediate supervisor wrote an investigative summary and recommended one of four options: "no further action"; "re-training"; "disciplinary action"; "pending." This process covered all cases of shots fired (when officers reported them), including those that wounded civilians or missed entirely. The supervising officer's report went up to the chain of command to the police chief. In the case of a civilian fatality, the chief constituted an internal board of inquiry and the Homicide Bureau also conducted a separate investigation, with results reviewed by the Wayne County Prosecutor's Office. The Homicide Bureau only shared findings with Internal Affairs if homicide investigators found evidence of police wrongdoing, which was very rare in fatal-force incidents.

Multiple academic studies, including the 1977 report by the Police Foundation on Police Use of Deadly Force, found that in Detroit and in American police departments in general, the internal and chain-of-command investigators were much more likely to find officer shootings to be "unjustified" when no one was wounded or killed by the gunshot. These cases generally resulted in firearms "re-training" or mild disciplinary action, generally a verbal or written "reprimand." Police departments almost always found officer shootings to be "justified" in cases of injury or death, when the consequences of a different finding could mean criminal charges and significant financial liability in a civil lawsuit. Critics of the internal investigation process continued to call for an independent civilian review board to conduct an impartial external investigation.

The 1977 Police Foundation study, reviewing Detroit and six other urban police departments, found that a "substantial majority" of fatal police shootings were "clearly justified" under use-of-force policies. The study also concluded that internal boards of inquiry almost always gave officers the benefit of the doubt, even in categories when the evidence indicated that they 1) falsely claimed self-defense, 2) might have planted weapons on the suspect, 3) lacked probable cause, 4) could have arrested a "fleeing felon" without resort to force, 5) escalated the situation unnecessarily through "rash or ill-considered action," or 6) shot people accidentally through "negligence or extreme nervousness" (examples detailed in chapter in gallery below). In sum, the Police Foundation study found that more restrictive use-of-force policies could reduce the number of civilian fatalities, but when officers violated the rules then the same "tendency [was] observed almost everywhere: to find an officer's conduct justified while noting any mistakes in the small print."

It's difficult to answer the question of how much Chief Hart's policy revisions and messaging changed the DPD's culture of policing and patterns of police violence starting in the mid-1970s. The Police Foundation study cited above analyzed fatal shootings and internal procedures during 1973 and 1974, when the DPD was still in transition from the deadly STRESS era under white political control to the partial reforms of the Coleman Young era. The next page explores identifiable police homicides in Detroit between 1974-1977 in detail, providing a timeline for assessing the impact of reforms to the "use-of-firearms" policy by Hart. Section II of this website provides additional evidence about the patterns of police homicides between 1978-1981, when the policy revisions had more time to take effect. But as many studies have shown, official use-of-force policies often have only limited impact on the discretion exercised by police officers on the street, especially when the "chain-of-command" hierarchy controls the investigative process and generally shows deference to the decision-making process and after-the-fact rationale provided by the individual officer.

A national-level analysis of urban police departments in the 1970s sponsored by the National Institute of Justice (excerpted in the gallery below at right) found that more restrictive policies did reduce the number of fatal shootings but had much less of an impact on the outcomes of internal investigative procedures for officers who still violated them. The NIJ report emphasized that even when reform-minded police chiefs sought to reduce fatal force incidents, they had to deal with pressure from the police officers union, the need to maintain "sufficient political support" within the department, the difficulty of controlling officer discretion in the field, and many other factors. This meant that in practice, police departments did not find officers to be at fault in fatal shootings unless their actions were clearly "grossly negligent" and seemed to be completely without any plausible justification.

DPD Policy Update (1977)-Firearms Regulations and Procedures [full policy including weapons training and specifications; 18 pages]

Sources for this Page

Detroit Police Department Manuals, Social Science, Education, and Religion Department, Detroit Public Library

Catherine H. Milton, et. al, Police Use of Deadly Force (Police Foundation, 1977), National Criminal Justice Reference Service, https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/41735.pdf

Arnold Binder, Peter Scharf, and Ray Gavin, Use of Deadly Force by Police Officers (Washington: National Institute of Justice, 1983), National Criminal Justice Reference Service, https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/Digitization/101489NCJRS.pdf

Edward Littlejohn, Geneva Smitherman, and Alida Quick, "Deadly Force and Its Effects on Police-Community Relations," Howard Law Journal 27:4 (1984), 1131-1184

Michigan Civil Rights Commission Staff Report, "The Use of Deadly Force by Law Enforcement Agencies," May 18, 1981, Folder: Police Use of Deadly Force, Box 654, William G. Milliken Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

Additional sources on DPD policy: David S. Grant, "New Squad Probes Shootings by Police," Detroit News, Sept. 10, 1975; Susan Watson, "Probe Hunts Gun-Happy Cops," Detroit Free Press, May 20, 1976; Louis Cook, "Police Professionalism is Saving Lives," Detroit Free Press, January 31, 1983

Delude v. Raasakka, 391 Mich. 296 (1974); People v. Doss, 406 Mich. 90 (1979)