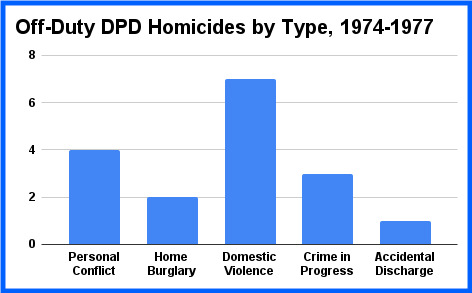

Off-Duty Homicides 1974-1977

Detroit police officers who were off duty shot and killed at least 17 people between 1974 and 1977. This total represents almost one-fourth of the 74 police homicides identified by the research team for this four-year period (the DPD acknowledged 100, an undercount). This page maps and profiles these off-duty police killings.

Off-duty police violence was a significant issue that DPD policies actively encouraged, in the sense of always being ready to fight crime, or did not adequately address, in the area of domestic violence. DPD regulations, as examined in more detail on the use-of-firearms policy page, required off-duty officers to carry a gun and be prepared to intervene to stop crime in progress. In 1979, when the city council opened an inquiry into the problem of civil litigation payouts for fatal shootings by off-duty officers, Chief William Hart explained the policy as an effective presumption that even officers off duty, "when necessary" because of criminal activity, "would be considered on duty and available for action 24 hours a day." The DPD defined off-duty officers as "plainclothes" officers and required them, like on-duty officers, to clearly identity themselves as police officers before taking action.

The DPD therefore classified most off-duty police shootings as "in the line of duty," except for the obvious criminal scenario of intimate family violence, and investigated them with the same benefit-of-the-doubt assumptions as with on-duty fatal force incidents. Most off-duty fatal shootings, however, involved either clearly criminal activity that victimized family members, or questionable situations where the off-duty officer aggressively escalated personal conflicts or property crime situations. In our project analysis, only 5 of the 17 off-duty fatal shootings between 1974 and 1977 appear clearly justified under DPD policy.

Swipe the map below to view the off-duty homicides in the Detroit's changing racial geography, as the city population expanded from 44.5% to 63% Black over the course of the 1970s. Hover over the dots for pop-up boxes with the incident description and other information.

Map of 17 Identified Homicides by Off-Duty Police Officers, in Detroit's Racial Geography (1970 and 1980 Census)

- Blue circles (7) = Domestic Violence

- Red circles (4) = Personal Conflict

- Black circles (3) = Crime in Progress

- Purple circles (2) = Home Burglary

- Green circle (1) = Accidental Discharge (Domestic)

Key Findings

- Prevalence (23% of total). Off-duty DPD officers were involved in 17 of the 74 total homicides identified by the research team. This is likely an undercount since DPD officers killed more than 100 people between 1974 and 1977.

- Justified (53%) and Unjustified (35%). Three officers were prosecuted in 5 of the 17 off-duty homicides, including one triple murder. All involved domestic violence and Black police officers. Another unjustified case was a murder-suicide, so no prosecution. Note that "justified homicide" is a legal determination made by the Wayne County Prosecutor, not an assessment by our project. In one case, Officer Harry Larsosa's homicide of Leon Cockran, the DPD recommended indictment but the prosecutor refused.

- Policy Violations/Wrongful Death (41% Definite; 29% Debatable). Our project asssesses that only 5 of the 17 off-duty homicides were clearly justifiable under DPD policy and state law and involved strong evidence of claims of self-defense or defense of others. Seven were clearly criminal, and five others arguably violated DPD use-of-firearms policy, could potentially have been prosecuted, and may well have been if the shooter had been a civilian not an officer. In one domestic violence case featured below involving Ernesta Weary, DPD institutional negligence constituted its own type of policy violation.

- Domestic Violence (47%). Eight of the 17 cases involved domestic violence where the officer killed a family member. This includes one case labeled "accidential discharge" in the graphic where an officer shot her husband. The prosecutor designated 2 of the domestic violence homicides as justifiable in self-defense or defense of others.

- "In the Line of Duty" (47%). The DPD classified 8 of the 17 homicides as "in the line of duty" based on the policy that off-duty officers should always be armed and ready to intervene to stop criminal activity. Only 3 of the 17 cases clearly involved this "crime in progress" scenario where officers confronted armed criminals. In four cases, off-duty officers shot people during personal conflicts that they arguably escalated or responded to with excessive force; three resulted in civil litigation. In two questionable unarmed "fleeing felon" scenarios, officers shot people who burglarized or robbed from their homes. One of these, the Leon Cockran case, is not classified as "in the line of duty" since the DPD (unsuccessfully) recommended prosecution.

- Civil Lawsuits (44% of "Line of Duty" Homicides). At least 4 of the 9 off-duty homicides considered "in the line of duty," meaning not involving domestic violence and criminal activity, resulted in civil lawsuits and substantial settlements by the City of Detroit. All of these cases involved white officers, and three involved white victims.

Off-Duty Homicides by Category: Questionable Cases/Personal Conflict

This section profiles 4 homicides that all occurred late at night and involved white off-duty officers who shot and killed young white males in personal conflict situations that escalated. Most involved alcohol, questionable claims of self-defense by the officer, and questionable allegations that the deceased was armed and/or dangerous (none with guns).

Larry Winstead (Oct. 24, 1974). Winstead, a 21-year-old white male and gas station attendant, was shot and killed by Officer Lindsay Joker in a restaurant parking lot around 3:00 am in an off-duty incident. Joker had been drinking alcohol with other policemen at a 4th Precinct party, but the investigating officers did not give him a breathalyzer test that night; Winstead was inebriated according to the autopsy report. Joker and Officer Eugene Napora both claimed that Winstead almost hit them with his car and then jumped out and came toward them “menacingly brandishing a razor.” Both stated that they identified themselves as police officers and drew their guns; Joker then shot and killed Winstead with a 9 mm revolver. There were no other witnesses. Winstead’s family filed a $12 million wrongful death lawsuit against the City of Detroit, arguing that Joker should have been suspended and unable to carry a firearm because of his pending trial on charges for felonious assault of another man in a high-profile incident. The lawsuit also said the shooting was “willful, malicious, and without cause.” The Detroit Free Press located multiple people who said that Officer Joker had previously harassed and threatened Winstead (Joker denied knowing him) and that they told the Homicide Bureau that the razor Winstead owned was not the one that Joker produced at the scene. Commissioner Tannian docked Joker 20 days pay for the Winstead shooting. (Visit this in-focus page for more on Lindsay Joker).

Thomas Stokes (June 19, 1975). Stokes, a 22-year-old white male, was shot and killed by off-duty officer Dennis Moran during an encounter around 2:45 am outside a restaurant on the far West Side. Moran and another off-duty officer said that they were at a drive-in window when a car with four occupants drove up and began “calling them names.” Moran said that Stokes exited the car with a bottle in a paper bag and swung the bottle at Moran, who identified himself as a police officer and “eventually was compelled to shoot.” The officers arrested two other men in the car for “investigation of aggravated assault” although there is no evidence they did anything threatening. The archival record is sparse but the incident is questionable regarding whether the officer needed to use fatal force in self-defense in such a situation. It is likely but not confirmed that all participants were white.

Kim Crowell and Keith Crowell (May 10, 1976). Kim and Keith Crowell, both 19-year-old white males and fraternal twins, were shot and killed by off-duty white Officer James Murphy after the unarmed pair allegedly attacked Murphy after midnight in a public park in Northwest Detroit. The twins had been drinking beer in Stoepel Park with two friends, who left before the incident. Murphy said that the twins began shouting obscenities at him while he was walking his German shepherd and then, after he identified himself as a police officer, began “scuffling” with him. Murphy claimed that he fired his .44 caliber magnum revolver after one twin reached for his gun and the other grabbed his dog. Kim was hit two times and Keith three times. Before he died, Kim Crowell repeatedly asked an emergency responder, “why did he shoot us?”

Family members said they could not believe the twins would attack a police officer with a dog, and an eyewitness challenged Murphy's account as well. A man watching from his window told the Detroit Free Press that the twins did not attack the police officer but they were having an argument; then one of the youths walked toward the officer; then Murphy shot them “once in rapid succession and then shot them again after they fell to the ground.” This eyewitness, who was Black, refused to talk to the police because he was on parole and said he feared police retaliation if he accused a white officer of wrongdoing. The prosecutor eventually compelled the eyewitness to speak to investigators, and he declined, as promised, to repeat what he had told reporters. Other witnesses who heard gunshots but did not see the incident said that at least thirty seconds elapsed between the rapid fire and the final shot, suggesting that Murphy might have shot at least one twin who was on the ground already wounded.

Sgt. Mary Jarrett of the Detroit Crime Lab found that the forensic evidence showed that Officer Murphy fired at least one shot at Keith Crowell as he lay on the ground, but the Wayne County Medical Examiner disagreed that the evidence was dispositive. The prosecutor sought a second opinion from the Michigan State Police Crime Lab, which backed the medical examiner. Jarrett also found that the bullets were not fired from close range, as would happen during a close-proximity struggle as described by Officer Murphy. After two months, Prosecutor William Cahalan cleared Officer Murphy and said the shootings “appeared to have been reasonable . . . as he saw it.” Cahalan also said he made the determination based on “the type of person Officer Murphy is, the type of person Keith Crowell is,” and the type of person the reluctant eyewitness with a criminal record was as well. (Murphy had been on the force for less than a year at the time of the incident and had four civilian complaints of brutality). Kathleen Crowell, the mother of the twins, called this a “whitewash” and said that her sons “would never attack anyone” and Murphy “knows in his heart he murdered those boys.”

The Crowell family filed a wrongful death lawsuit seeking $2 million each from Officer Murphy and the City of Detroit. The Law Department advised the City Council not to pay for the officer’s defense, because of the high likelihood of an unfavorable verdict, but they did so anyway under the "in the line of duty" policy. In the deposition, Officer Murphy claimed that Keith Crowell threatened him and said “get the gun,” and that Kim Crowell said “I’ll kill you” before he fired. The Law Department memo (at right) took Officer Murphy’s side on the facts of the case and did not address the countervailing evidence. The Law Department recommended settlement because of the likelihood that a jury would return a wrongful death verdict and an even greater financial award because the jury would “require strong proof that an armed police officer has exhausted every possibility of self defense before firing his gun.” In 1979, the city council settled the lawsuit for $400,000.

Category 2: Fleeing from Home Burglaries

This section features two questionable homicides that occurred when off-duty officers responded with extreme aggression to burglary attempts or property thefts from their homes by unarmed young males. As detailed on the previous page, on-duty officers frequently shot unarmed "fleeing felons" during the mid-1970s, and the DPD did not actively discourage fatal force against low-level property suspects until 1977.

Michael O'Neal (Nov. 19, 1974). O'Neal, an 18-year-old white male, was shot and killed by off-duty Officer Michael Trompak after the teenager allegedly stole a sports car from Trompak's Northwest Detroit home around 1 am. Trompak said that he heard someone inside his house grabbing the car keys and fired a shot as the driver was speeding off. He reported the incident to the police but then went looking for the thief in his wife's car. Trompak located the stolen vehicle and gave chase at high speed, eventually cornering O'Neal. Trompak reported that he exited the vehicle and approached the car on foot with gun drawn, and then O'Neal "gunned the engine and tried to run him down." Trompak fired several shots, hitting O'Neal in the chest and abdomen. There were no other reported witnesses, and Trompak's account followed the common self-defense script, almost every time that officers shot someone in a car, that the driver had tried to run them over. Trompak was later involved in two other off-duty incidents: in 1977, he shot and wounded two people in a car on the Chrysler Freeway after they allegedly shot at him; and in 1978, he was arrested and prosecuted for selling firearms without a license.

Leon Cockran (Sept. 23, 1975). Cockran, a 25-year-old Black male, was shot and killed by off-duty Officer Harry Larsosa after Cockran and a companion allegedly tried to break into Larsosa's house in a neighborhood on the East Side. Larsosa claimed that he shot Cockran, who was unarmed, as he fled. More than a year later, after Larsosa was arrested for a large number of unpaid traffic tickets, the Detroit News reported that the DPD had sought a murder warrant for Larsosa but the Wayne County Prosecutor denied the request. The Detroit Free Press reported allegations that Larsosa shot Cockran in the back while he was on the ground. Newspaper accounts stated that after the prosecutor's denial, the DPD put Larsosa on a one-year probation and docked six weeks pay for filing a false police report, and then fired him after the traffic ticket arrest. Cockran's estate filed a civil lawsuit against Larsosa, and the Law Department recommended denial of legal representation, which only happened when they believed that the officer had not acted "in good faith." In a 1976 letter to the City Council, Commissioner William Hart asserted that Larsosa was justified in firing at a "fleeing felon" and was "taking police action," despite being at home and off duty. But Hart also admitted "certain inconsistencies" and "inappropriate behavior" in the case, and said "the investigative facts uncovered in this case are sensitive in nature and should not be aired in an open forum." Note: some newspaper articles reported the deceased as Leander Crockran.

Category 3: Serious Crimes in Progress

The DPD's main justification for requiring officers to be armed at all times was so they could stop dangerous crimes in progress by protecting civilians. This scenario only accounted for two of the off-duty homicides, covered in this section along with a third where the officer himself was the robbery target. These cases tended to involve Black officers who lived in or near areas with higher rates of street crime and gun violence. All of the cases below involved armed assailants and plausible claims of self-defense or defense of others, although one suspect was fleeing when shot from behind.

George Cottle III (Feb. 13, 1974). Cottle, a 26-year-old Black male, was shot and killed by off-duty Officer Willie Merchant. Cottle III and an accomplice allegedly attempted to rob Merchant and his girlfriend in a restaurant parking lot. Merchant shot Cottle twice in the chest and shot at the accomplice in a car speeding away. Cottle allegedly fired three times but missed Merchant. It is not clear who fired first.

Richard Shelburn (May 24, 1975). Shelburn, a 23-year-old Black male, was shot and killed by off-duty Officer Frederick Davis Jr. in Northwest Detroit after Shelburn allegedly shot at a van and killed one of two people inside. Police said that Shelburn ran away when Davis identified himself. Davis fired three shots at the fleeing man and killed him.

Waltes E. Gordon (Sept. 24, 1977). Gordon, a 41-year-old Black male, was shot and killed by off-duty Officer James Dees after Gordon allegedly shot another man at an East Side gas station. Dees said he identified himself as a police officer and ordered Gordon to drop the weapon, a shotgun. When Gordon instead fired at Dees, the officer returned fire and killed Gordon with multiple shots. Witnesses confirmed the officer's account.

Category 4: Domestic Violence

In 4 of the 8 cases of domestic violence homicides featured in this section, the officer involved killed a family member(s) and was prosecuted for murder. A fifth officer committed suicide after committing murder. In two domestic violence scenarios, the officer was found to be justified in self-defense or defense of others. In one case, an officer was prosecuted for reckless endangerment after killing her husband in an alleged accident.

Seven of the eight domestic violence homicides in this four-year time period happened in a very concentrated flurry between November 1975 and January 1976. One of the officers whose domestic homicide was ruled justifiable also killed himself in the aftermath. This led to a significant amount of media coverage and heightened concern about the psychological stresses on police officers and whether there was something in the profession itself that created a propensity for domestic violence and suicide. Critics also argued that psychiatric screening of new recruits, which the DPD had only instituted in 1969, had been inadequate because of the large number of officers hired in recent years.

Between 1973 and 1978, the DPD evaluated 327 officers as "emotionally disturbed" and required them to undergo extensive psychiatric counseling; 149 of this group were classified as a "potential danger to themselves or others" and prohibited from carrying firearms until cleared by a psychiatrist. Some, the so-called "rubber gun squad," had to stay in office jobs indefinitely or permanently. Eleven DPD officers also committed suicide in a three-year period between mid-1974 and mid-1977, and the department was also slowly beginning to acknowledge and address the problems of alcoholism and domestic violence within its ranks.

James Schmitt (Nov. 27, 1975). Schmitt, a 32-year-old white male, was shot and killed by off-duty Officer Gerald Stephens, who had just married Schmitt's recently divorced wife, who also was a police officer. Stephens and his wife were guests at her mother's house on the East Side for Thanksgiving when Schmitt arrived to pick up furniture. Stephens initially offered to help, but the men began arguing over the division of furniture related to the divorce settlement. Schmitt allegedly attempted to attack Stephens with an axe, and so Stephens shot Schmitt in the chest, killing him. A police board cleared Stephens of wrongdoing on the grounds of self-defense. Stephens died by suicide the following January, reportedly distraught over the effects of the shooting on his family and work relationships.

Milton Bobo (Nov. 30, 1975). Bobo, a 27-year-old Black male, was shot and killed by DPD cadet Cecila Bobo, his wife, who said she wanted to practice loading her .38 caliber police revolver with what she thought were dummy bullets. Cecila Bobo, a Black woman, who was set to graduate in two weeks from the Detroit Police Academy, said she mixed up the dummy and live bullets and shot her husband in the head accidentally as he lay in bed. An autopsy showed, however, that Milton Bobo may have raised his hands in a defensive manner and that the gun was five to seven inches from his forehead when a bullet went through his hand and killed him. Cecila Bobo said she pointed at him while she was practicing and he said, "don't play with that" and put his hands in front of his face, then the gun discharged. She was charged with careless and reckless use of a firearm, causing death, and barred from police academy graduation. Cecilia Bobo was convicted in an April 1977 trial.

Ernesta Weary (Dec. 12, 1975). Weary, a 28-year-old Black female, was shot and killed by her estranged husband, Officer George Weary. While off duty, the officer broke into Ernesta's parents' home in Northeast Detroit. As their two children hid downstairs, George chased Ernesta ouside and then shot her in the chest before shooting himself. Ernesta had called the 11th Precinct station house two days before the shooting saying that George threatened to kill her and asking for protection. Officers there told the newspapers that they did not know anything about her request, but the DPD later said that the report was being investigated at the time of the murder-suicide. The DPD's inaction raises questions about negligence and its approach to domestic violence situations, as the Michigan Chronicle reported. This was part of a broader critique raised by women's groups and other critics of the DPD's insufficient attention to the problem of domestic violence more generally.

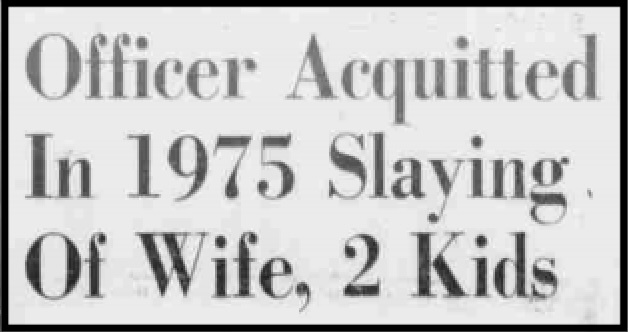

Becky, Pamela, and Cassandra Harrington (Dec. 19, 1975). Becky Harrington, a 28-year-old Black woman; Pamela Harrington, a 9-year-old Black girl; and Cassandra Harrington, a 4-year-old Black girl, were shot and killed by Officer Paul L. Harrington, Becky's husband and the girls' father. All three were found shot in the head at Becky's nephew's house in Northwest Detroit around a week after the couple separated. Paul Harrington, who had been receiving psychiatric treatment related to his service in Vietnam, reported the incidents himself and was taken to the psychiatric wing of Detroit General Hospital, where he tried to commit suicide multiple times. He was indicted on three charges of first-degree murder but acquitted in a bench trial by reason of insanity. After release from a psychiatric institution, Harrington sought to become a police officer again, but the DPD refused. In 1999, Paul Harrington shot and killed his second wife, Wanda Harrington, and his 3-year-old son, Brian, and was convicted of first-degree murder in both cases.

Joyce Wellington (Jan. 17, 1976). Wellington, a 22-year-old Black female, was shot and killed by off-duty Officer Thomas Morris, whom newspapers described as her boyfriend, after Morris broke into her Northwest Detroit apartment around 3:30 am. According to Wellington's housemate, another man was in Wellington's bedroom when Morris called and said that he would kick the door in, and then he did. Morris shot Wellington in the chest, killing her, and then asked the roommate to call police and waited until they arrived. After Morris was charged with first-degree murder, a jury found him guilty of manslaughter, and the judge sentenced him to 2-15 years in prison.

Clyde Swanson (Dec. 17, 1977). Swanson, a 19-year-old Black male, was shot and killed by off-duty Officer Charlotte Pearson, his half-sister, as he was allegedly beating their mother. Officer Pearson said she tried and failed to stop Clyde Swanson and so then emptied her service revolver, hitting him three times. The shooting was one of two in this category designated as a justifiable homicide by investigators.

Sources for this Page

Detroit City Clerk’s Archives and Records Management Division, Detroit, Michigan

Maryann Mahaffey Papers, Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library

Coleman A. Young Mayoral Papers, Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library

Coverage of individual cases from the Detroit Free Press; Detroit News; Michigan Chronicle. Citations for individual articles can be found in the pop-up boxes on the map.

Additional sources for Michael Trompak: "2 Wounded in Gunfight on Freeway," Detroit Free Press, Feb. 19, 1977; "Cop Charged with Illegal Sale of Guns," Detroit Free Press, Feb. 7, 1978

Additional sources for Category 4: "Officer Given Mental Tests," Detroit Free Press, Dec. 21, 1975 (including Bannon quotation); "3 Cop Suicides in Five Weeks," Michigan Chronicle, Jan. 24, 1976; Jack Kresnak, "Armed, Dangerous: Unbalanced Cop," Detroit Free Press, April 2, 1978