911 Complaints and Reform

By the 1970s, the 911 Emergency Response System in Detroit was in its early days and experiencing many difficulties. It was not uncommon for dispatchers to struggle to pass the correct information onto the police and EMS for emergency services to arrive late on scene. The public service video to the left discusses the importance of the EMS services, which ran through the same services as those that dispatched police. In an unusual manner, the video discourages people to call 911 unless the issue is an absolute emergency which indicated that the 911 services were not entirely prepared to deal with the emergencies of Detroit.

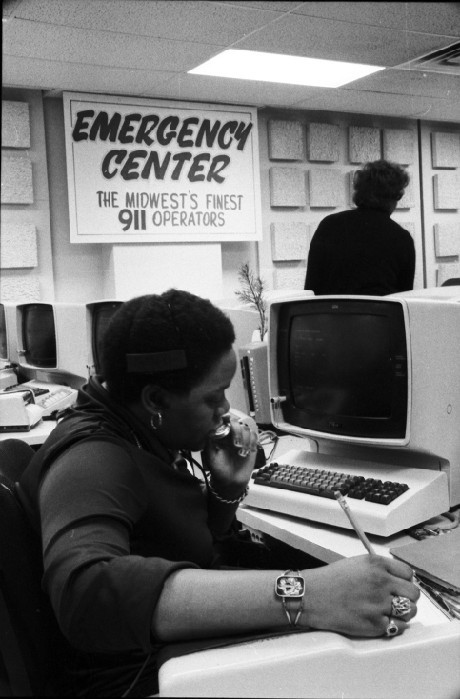

The Emergency Response System, known today as 911, began in Detroit on October 31, 1973, when Michigan Bell Telephone coordinated with Detroit city officials to establish a system that would link the people of Detroit to the Detroit Police Department, Detroit Fire Department, and medical assistance. Upon release, Phillip G. Tannian, a mayoral aide, said that the system involved "no recordings, no busy signal. No wait longer than the second ring in almost every case". This narrative later proved not to be entirely correct as many problems frequently arose within the 911 system throughout its early days in Detroit. In 1976, the Michigan Bell System made all 911 calls from payphones free through a new Dial Tone First service that bypassed the regular system, allowing people to call 911 without entering coins. Despite this attempt to make 911 more accessible, there were still problems with how few people were able to reach 911 and these people were often the people in Detroit with the lowest incomes. In 1986, an article in the Detroit Free Press reported that the position of a 911 operator was incredibly stressful due to the tidal wave of calls they received. Nineteen trained operators handled over 400 calls an hour, many of which were seen to be calls that should have been handled by non-emergency services. For a city with thousands of citizens, the Emergency Response System had only been allocated enough money to support a staff of nineteen people. These operators were then forced to make tough decisions about the priorities of numerous calls and quickly decide whether or not the call warranted a police response before the next call. It was not until 1987, that 911 operators began prioritizing certain calls over others and even then, domestic violence calls were made to be a low priority. Many in Detroit believed that the negligence of the Emergency Response System was a deliberate form of underpolicing and an important example of the City of Detroit and the Detroit Police Department not prioritizing certain crimes.

The Case of Anita Burris

One incident ignited anger within Detroit communities over the competency of the 911 system. In 1974, 911 operator, Anita Burris, received a call from an elderly couple regarding "young persons" breaking into their home. Burris told the couple to find out what the young people wanted and then proceeded to stay on the line for six more minutes without dispatching any officers. While the wife of the couple was on the phone with Burris, she and her husband were both fatally shot. Burris then disconnected the line and wrote the dispatch ticket as a routine burglary. Police found the bodies of the couple 25 minutes later. Despite the fact that the couple was shot 24 times, Burris argued that she was unaware that the sound she could hear was gunshots. Burris was subsequently fired by then Chief Phillip G. Tannian until a civilian department executive heard her appeal and overturned Tannian's decision. Burris only received a three-day suspension for this incident. In 1978, Burris was working as a 911 operator once again and received a call that a man was slumped over in his car and was unresponsive but still alive. Allegedly, Burris then unknowingly referred the call to an unmanned station and no further action was taken. A second call was made that was routed to a different operator and by the time officers were sent out to the car, the man had died. In response to this incident, Burris was removed from her duties of answering 911 calls but was still employed by the City of Detroit.

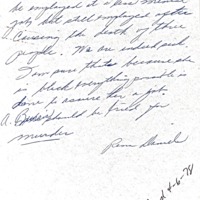

This incident triggered a huge public outcry from local residents who felt that their emergencies were not being prioritized by the city. Some wrote in letters to city council members and one letter demanded that Burris be tried for murder. The lack of discipline for 911 operators for negligence troubled many and was an example of one of many ways that the city would protect its civil servants even to the detriment of civilians. Many questioned how a woman had been able to maintain her position as a 911 operator after the first incident - especially when the role of a 911 operator was highly paid and sought after by many. This case initiated an important discussion over the issues that came from a faulty 911 system. People were asking why the city was protecting an employee whose mistakes were costing lives and were hoping for drastic changes to the system. Detroit officials defended their actions by stating that a 911 operator was not responsible for lack of police responsiveness and that they struggled to handle the important calls with the huge influx of non-emergency calls that came in daily. The city began an investigation but it was not long before more cases of negligence within the system were revealed.

Other Incidents Become Known

One man reported that he and his wife, Mr & Mrs. Thompson, were driving home at night on December 20, 1979, and witnessed a head-on collision between two vehicles. Passengers in both vehicles were gravely injured and Mrs. Thompson ran to a nearby police station for help while Mr. Thompson attempted to give any assistance possible to the passengers. The collision was causing a roadblock and police had still not dispatched officers by the time that Mrs. Thompson returned from the station. When EMS arrived, Mr. Thompson went to the police station and demanded to know why they did not dispatch officers when Mrs. Thompson asked them to. The Sergeant on duty responded by saying that it was not a police matter and that they had done everything that was required of them. After questioning the officers for more information, Mr. Thompson was placed under arrest for disturbing the police.

In another case, a man called 911 to report a stolen car that had been parked outside his house. His call rang for twenty minutes without an answer and after a short investigation, it was discovered that one of the main 911 lines had been malfunctioning for hours and many calls had gone unanswered. Lt. Joyce May of the DPD 911 Department responded to the allegations of a malfunctioning line by stating "We're not having any problems with our phones - the longest wait for anyone to call 911 is 11 seconds." The DPD was not only consistently neglecting their responsibility to serve the people of Detroit that called 911 but they also persistently denied all allegations that the 911 system was not working.

Letters to Detroit City Councilwoman, Maryann Mahaffey, revealed many other cases where police had failed to respond to scenes. 911 calls had been made multiple times on all occasions and yet went ignored. Many people believed that it was certain neighborhoods within Detroit that were being neglected by 911 services. One letter discussed an incident where a local Food Store was vandalized and the electrical power system destroyed - causing over $20,000 in damage. Police were called at 8:30 AM on the day that the damage was discovered and again at 5:00 PM when the police had failed to respond to the earlier call. The police never responded to the call and said to a reporter that the complainant had to appear in-person to a precinct to make an official report. Members of the community were outraged at the police response and felt that they were partly responsible for the number of business-owners leaving the city. The Vice-Chairman of the Wayne County Board of Commissioners said in a letter responding to this incident that he hoped that police departments would adjust their behavior to correct their "unwarranted continued practices" before the City of Detroit was known as "Plywood City".

In the most extreme cases, the lack of 911 response led to serious injuries and even fatalities. One elderly man, Leo Salakin called 911 when a man entered his house on the Northwest side and began to attack him and his wife. The 911 operator felt that the situation did not warrant a police or EMS response and took no further action. Leo's wife, Pearl, died from her injuries after being raped and beaten and Leo, himself, was badly injured. The couple was found three days after the attack by friends. Leo sued the city for the negligence exhibited by the 911 operator and settled in court for $1 million. He used the money to establish a foundation and donated almost half of his winnings to the City of Detroit to support community programs for children and create local recreational facilities. This case is noticeably similar to the Annita Burris incident where another elderly couple was attacked and ignored by 911. As with most cases of police neglect, these incidents proved to demonstrate a clear pattern. Those with the least means to defend themselves were often those that suffered the most at the hands of police neglect.

One case that caught the attention of the media was the death of nine-year-old, Michael Newsome on the Northeast side of Detroit. Michael was asleep in an upstairs bedroom of his home when a fire began in his kitchen. His older siblings were able to leave the house but the fire had spread and prevented Michael from being able to get out. Neighbors called 911 numerous times while others attempted to reach Michael. None of the people that called 911 were able to reach anyone and were on hold for over 20 minutes. Following no response from the Detroit Fire and Police departments, neighbors reached out to the Hamtramck Fire Department - who arrived before firefighters from Detroit. Damian Brown, Michael's 11-year-old best friend and neighbor, said to reporters "If they (firefighters) would have come about seven minutes earlier, they would have saved my best friend's life." Michael's death devasted an entire neighborhood and outraged many in the City. In their usual style, city officials responded by stating that they were not aware of the incident or how soon the calls were answered. Many blamed the Fire Department but others felt that the information was not forwarded from 911 to the Fire Department.

As with any system in its early days, Detroit's Emergency Response System was flawed in many ways. However, the issues that many reported having with the 911 system was more to do with its operation than with its mechanical flaws. Operators would frequently not forward calls onto the appropriate department or mark them as a low priority call. Elderly citizens, as well as low-income neighborhoods, suffered the most at the hands of the faults of the 911 system. Reforms were made to attempt to improve the response times but Detroit struggled to provide the money needed to make the system work. It was not until the late 90s that the system became reliable and still today, many believe that certain areas are not prioritized in the same manner as others.

Sources used for this page:

Two Articles. Maryann Mahaffey Papers. April 4, 1978. Box 39, Folder 5. Burton Historical Library, Detroit, Michigan

Letter to Mahaffey about 911. Maryann Mahaffey Papers. April 4, 1978. Box 39, Folder 5. Burton Historical Library, Detroit, Michigan

Just Dial 911 In Emergency, September 1 1973, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Detroit Free Press

Free 911 Calls Begin on Pay Phones, October 19, 1976, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Detroit Free Press

City ponders new equipment for 911 phone network, May 12 1986, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Detroit Free Press

Questions on 911 Service, May 14, 1976, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Detroit Free Press

911 dialer hits glitch; calls go unanswered, July 25, 1988, Joel Thurtell, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Detroit Free Press

Neighbors blame 911 in fire death, November 10 1985, Jon Pepper, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Detroit Free Press