Aftermath of the Kercheval Incident

On August 9, 1966, long-standing tensions between the police and residents of an East Side neighborhood ignited when police officers arrested three men associated with the Afro-American Youth Movement (AAYM) for loitering on the sidewalk. Detroiters feared that the unrest that followed the arrests signaled the beginning of a violent city-wide riot, but after four days the disturbance became known as “the riot that didn’t happen.” The police department, aided by a “fortuitous rain” and the cooperation of the neighborhood’s residents, in addition to a massive show of force, quelled the minor scuffles that did break out. The DPD's leadership immediately boasted to the nation of its successful 'riot prevention' policies and also charged several members of the Afro-American Youth Movement with conspiracy to riot, leading to a trial and further investigations of black power militants. These charges helped to destroy the AAYM, the leader of Detroit's direct action anti-police brutality movement, which was clearly a DPD priority.

Detroit was divided into factions that disagreed about the broader significance of the Kercheval Incident. In its wake, community organizations and city officials collaborated to produce a set of new programs to prevent future violent outbreaks, but another “long, hot summer” awaited the city in 1967.

Who started the Kercheval Incident? What caused it to end? Why did it happen? Detroit newspapers offered different answers to these questions, reflecting and reinforcing divisions within the city.

The Verdict in the Newspapers

The white press, echoing Mayor Jerome Cavanagh and Police Commissioner Ray Girardin, commended the police force for the way it handled the incident. The photographs that the Detroit News and the Detroit Free Press published during the incident depict the police as a steadying force bringing order to the unruly neighborhood and reflect the mainstream white media's support of the Detroit Police Department (DPD). The Detroit News, at the time the most conservative of Detroit's major newspapers, reported that patrolmen showed "a remarkable exhibition of . . . control and restraint which even awed some of the commanding officers themselves." In contrast to the cool-headed officers, the newspaper characterized ACME-AAYM as "a group whose moving spirit is automatic hostility to and harassment of the police, spoiling for the violent confrontation they apparently deem inevitable." The News dismissed ACME-AAYM's claims of harassment by the police and attributed the incident to a handful of "trouble-seekers."

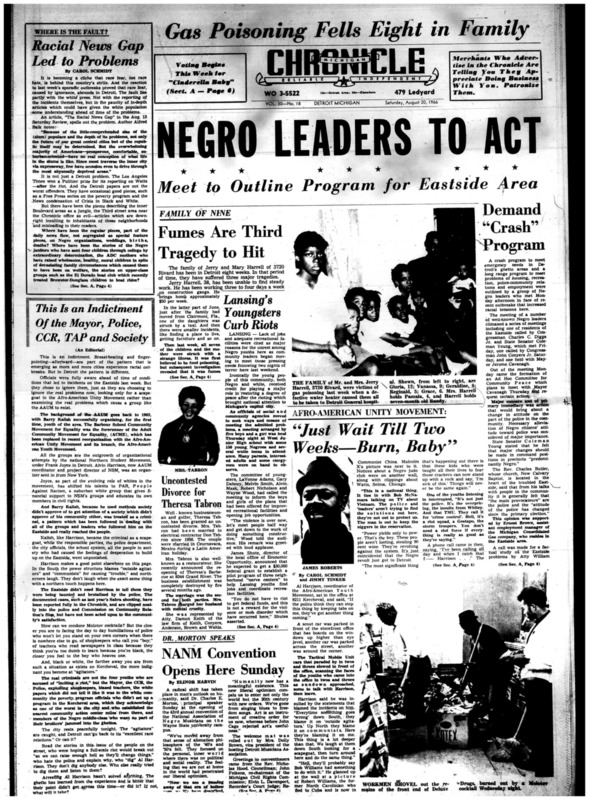

The Michigan Chronicle, Detroit's African American newspaper, offered a more complicated view of the causes and events of the incident. Reflecting the perspectives of Detroit’s black middle class, the paper reprimanded the young “troublemakers” who were involved in the incident but recognized the systemic failures that contributed to the poor living conditions in the neighborhood in a way that the white newspapers did not. In an editorial titled "This is an Indictment of the Mayor, Police, CCR, TAP and Society" the Chronicle argued:

“The real criminals are not the four youths who are accused of ‘inciting a riot,’ but the Mayor, the [Commission on Community Relations], the Police, exploiting shopkeepers, biased teachers, the white papers which did not tell it like it was to the white community, the poverty program officials who didn’t set up a program in the Kercheval area, which they acknowledge as one of the worst in the city and who established the nearest community action center miles from there, and members of the Negro middle-class who want no part of their brothers jammed into the ghettos.”

Chronicle reporters also interviewed young AAYM members and included their perspectives.

“We don’t want better recreation, more lights, we just want to be able to have what we’re qualified for, to be able to go in and apply for a job and not be turned down in favor of some peckerhead who hasn’t got a bunch of traffic tickets on his record like we all do, thanks to them [the police].”“Let Whitey leave our neighborhoods. Let him open a liquor store out in Grosse Pointe where they’ll respect him. Bet he won’t call his customers "boys" out there. Let us control our own neighborhoods.”“Man, I bet Mayor Cavanagh is glad. Him and that bunch of ‘leaders’ who’ve been meeting like crazy the past couple days. But they haven’t asked none of us to the meetings.”

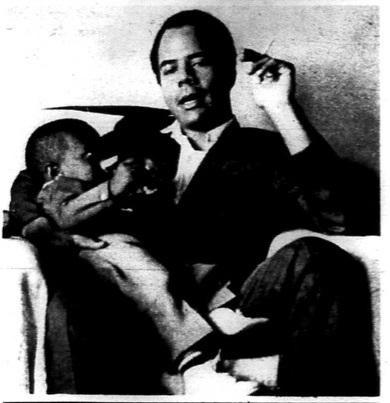

The Fifth Estate, an underground radical newspaper run by white New Leftists, was one of the few sources to report the story from the AAYM’s perspective. It called the mini-riot a “fantasy . . . staged by the Detroit Police with the assistance of the prosecutor’s office, city government, and the press.” The paper interviewed Al Harrison, director of the AAYM, who said that “what happened was a response on the part of an oppressed people to the most obvious form of their oppression: the police department." Harrison explained that during the two and a half years that ACME-AAYM had been in operation on the East Side, the organization had tried to “create a power bloc” to push against the white power structure, and the police resented those efforts and set "out to destroy the organization."

"Community Peace": Through Civil Rights Reforms or DPD Riot Control?

As these different perspectives on the Kercheval Incident show, race, class, and debates about the state of police-community relations divided Detroit. The incident rattled the city and caused municipal officials, civil rights leaders, and community organizations to debate what to do in its wake. They developed plans to improve living conditions in the Kercheval-Pennsylvania area with the goal of preventing future outbreaks of violence.

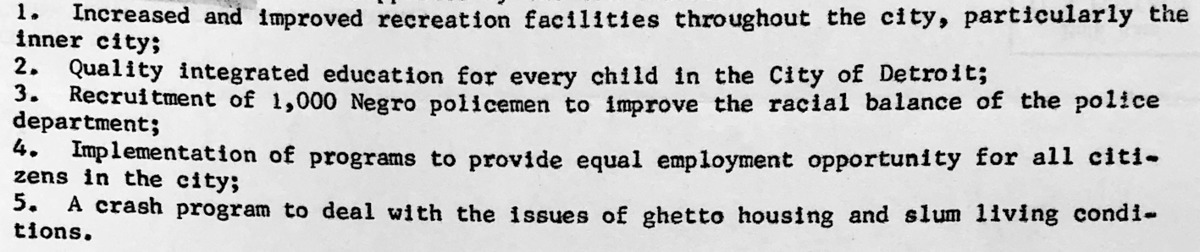

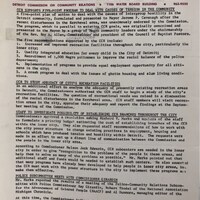

A group of African American community leaders calling themselves the Ad Hoc Committee on Community Peace presented a five-point plan to Mayor Cavanagh. The plan, endorsed by the Detroit Commission on Community Relations (DCCR), essentially called on the liberal Cavanagh administration to live up to its promises of a "total war on poverty" and equal opportunity regardless of race:

The Ad Hoc Committee on Community Peace, which included clergymen, two congressmen, civil rights leaders, and AAYM leader Alvin Harrison, requested that Cavanagh implement a crash program for civil rights “to make urban life livable and meaningful.” The group argued that “slum living conditions,” the lack of jobs, and the poor quality of education in areas such as the 5th Precinct discouraged young people and made them more likely to rebel. Additionally, by providing recreational facilities and youth programs, the city would give young people a place to gather and reduce the amount of contact they had with the police.

In October, DCCR officials met with the Parks Department and identified recreational facilities in the Kercheval-Pennsylvania area that needed to be improved. The city made plans to renovate two basketball courts in the neighborhood and construct five pools in parks around the city. The DCCR also recognized that it could diagnose community relations problems faster if it opened offices throughout the city (see right). The DCCR proposed a plan to establish four new outposts in Total Action Against Poverty (TAP) centers so that it could respond to problems as they arose. These proposals would improve living conditions in areas such as the Kercheval-Pennsylvania neighborhood, but the DCCR recognized that additional steps were needed to fix the problem at the heart of the incident--the police department’s tense relationship with the neighborhood’s residents.

Police-community tensions, of course, were directly linked to the Cavanagh administration's embrace of militarized policing, discretionary policies that encouraged harassment of young black men on the street, and support for stop-and-frisk crackdowns. The DCCR again recommended that the city “improve the racial balance” of the DPD to reduce racial tensions. Despite claims that the DPD had intensified its efforts to hire a more diverse police force, in October 1966 only about 200 out of 4,300 officers on the force were African American. DCCR director Richard Marks urged Mayor Cavanagh to invest in the recruitment of black officers, especially “now that we have demonstrated our willingness to spend $570,000 for extra police manpower caused by the Kercheval Incident of August 9.” Making this investment, he argued, would improve police-community relations and prevent future violent—and expensive—confrontations. Commissioner Girardin again enlisted the help of black clergymen to ramp up its recruitment efforts.

The Kercheval Incident convinced Commissioner Girardin and Mayor Cavanagh that the DPD was prepared to handle a larger violent outbreak, and as a result, the city made few alterations to its riot-prevention plans. Although a few officers had used unnecessary force or muttered racial slurs during the incident, the police force quelled the unrest with relative ease. To the administration, the Kercheval Incident demonstrated the success of the DPD's efforts to professionalize the police force and cemented Detroit's reputation as a model city.

Cavanagh later admitted, in an interview with the historian Sidney Fine, that the Kercheval Incident had “lulled” the city government into “a false sense of its ability to keep disturbances under control.” The police force had been aided by the rain and the cooperation of many residents. Without these buffers, the Kercheval Incident could have grown too large for the department to contain. Although the proposals to improve living conditions and alter the composition of the police force were a good start, the problems they were designed to fix had deep roots and the city’s plans were implemented slowly.

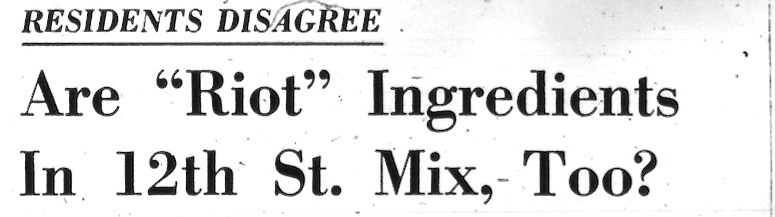

One month after the Kercheval Incident, the Michigan Chronicle asked, “Are ‘Riot’ Ingredients in 12th Street Mix, Too?” The neighborhood surrounding 12th Street resembled that of Kercheval Avenue, and its young residents also had a contentious relationship with the police department. Residents of the West Side neighborhood disagreed with one another, but one eerily predicted the violence that would come in the summer of 1967.

The DPD Claims Victory, Charges Activists with Inciting a Riot, and a Conspiracy Trial Mystery

Commissioner Girardin's August 1966 report to the mayor on "contingency planning for major disorders" praised the DPD officers involved in the Kercheval Incident for their "admirable courage" and professionalism. Girardin also directly blamed the disturbance on the Afro-American Youth Movement and ACME, referring to the political activists who were standing on the street corner as "known police characters," an implication that they were criminals. In fact, the men were "known police characters" because the DPD's Criminal Intelligence Bureau kept them under surveillance for their radical politics, and because police officers frequently arrested and cited them as punishment for their political activism.

The DPD arrested and charged four African American men with inciting to riot during the Kercheval Incident: Alvin Harrison, Thomas Abston, Moses Wedlow, and James Robert. They also arrested three other Afro-American Youth Movement members on the sidewalk encounter charges of loitering, resisting arrest, and obstructing the police: Clarence Reed, Wilbert McClendon, and Noble Smith.

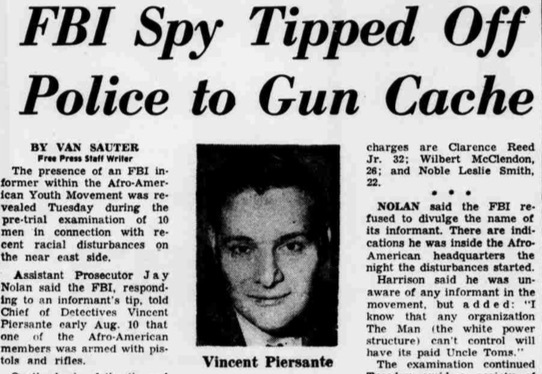

The pretrial examination in August 1966 revealed that the FBI had an informant working inside AAYM headquarters, and that the testimony of this unnamed informant had led to the arrest of General Baker and two other well-known Detroit radicals on weapons charges during the Kercheval Incident. When asked about the FBI spy, AAYM leader Alvin Harrison said he did not know anything about it, but the white power structure would always send "paid Uncle Toms" to do its dirty work.

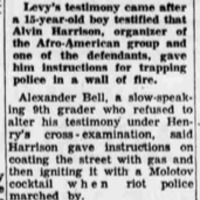

The hearing also introduced testimony alleging that Harrison had urged two young African American boys to "get our rights . . . even if we have to break car and store windows," that Thomas Abston had encouraged them to "burn the police" with Molotov cocktails, and that Moses Wedlow had urged AAYM members to "go home and get your guns. . . . We'll throw rocks to break windows and when the police arrive we'll shoot them." Under cross-examination by the defense attorney, well-known Detroit radical Milton Henry, the teenagers insisted that Harrison also urged them to throw Molotov cocktails at the police and trap them in a "wall of fire." Despite this eyewitness testimony, charges against Abston were dismissed by the Wayne County judge after several days of hearings that newspaper reporters repeatedly decribed as procedurally unusual. Harrison and Wedlow were bound over for trial, along with the AAYM members charged with loitering: Reed, McClendon, and Robert.

The first Kercheval-related trial in early 1967, for weapons violations by General Baker and Glanton Dowdell of the League of Revolutionary Black Workers, who had been arrested after a tip from the FBI informant inside AAYM headquarters, raised more questions. During the proceedings, an FBI agent refused to reveal the identity of its undercover agent, and DPD surveillance officers expressed fear that the man would be killed by radicals if exposed. In March, Baker and Dowdell received five-year probationary sentences (possession of the weapons was not illegal, and there was no evidence of criminal intent beyond the testimony of the FBI's unidentified informant).

In May 1967, Wilbert McClendon and Clarence Reed, the two AAYM members from the community who refused to move off the sidewalk, received prison sentences of 1.5 to 2 years for obstructing police officers in the performance of duty.

The trials of Harrison and Wedlow, who allegedly urged violent resistance, apparently never happened. Wedlow ended up in prison in Indiana, and disappears from the story. In February 1967, Harrison was bound over for trial, with an August date scheduled. This did not take place, although it should be noted that the courts were jammed after the 1967 Uprising. Harrison then appears in the Detroit newspapers in an October 13, 1967, Detroit Free Press article briefly noting his inclusion on the New Detroit Committee, a group of "the city's most influential civil leaders," with a mission to rebuild riot-ravaged Detroit. On March 22, 1969, the Detroit News reported that Alvin Harrison had entered a guilty plea to a reduced charge of creating a public disturbance and received a suspended sentence. He was not present and had moved to Cleveland, according to defense attorney Milton Henry. The DPD's Special Investigation Bureau, a.k.a. the "Red Squad," negotiated this unusual arrangement with the Wayne County prosecutor's blessing.

Then Alvin Harrison disappears from the historical record. This is a mystery that demands further exploration.

The FBI/DPD Informant: Unraveling the Mystery

The strongest evidence that Harrison himself worked undercover for the FBI and DPD comes from a 1968 congressional hearing on "Riots, Civil and Criminal Disorders," conducted by the right-wing Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations in the U.S. Senate in March 1968. The hearing, held in Detroit eight months after the 1967 Uprising, sought to prove that a conspiracy of black radicals had caused that violent event. The right-wing congressmen also pursued a theory that traced the "Detroit riot" of 1967 to the role of black radicals in previous disturbances, including the protests after the 1963 DPD killing of Cynthia Scott and the Kercheval Incident of 1966. As part of this inquiry, the Senate subcommittee called Detective Lt. William McCoy, who was in charge of the Demonstration Detail of the DPD's Special Investigation Bureau. This unit, part of the so-called Red Squad, conducted political surveillance on civil rights and black power organizations and activists, among other "intelligence gathering" activities. McCoy's testimony displayed detailed knowledge of ACME and AAYM activities and internal conversations since 1965, and of some of the group's individual members since 1963, further evidence of the breadth and scope of DPD surveillance operations.

Detective McCoy began by retelling the DPD's version of the Kercheval Incident and of the "reliable source" that informed the Special Investigation Bureau of General Baker and his weapons. Then he testified that on August 11, the third day of the Kercheval disturbance, DPD surveillance officers saw a man outside AAYM headquarters "give to a juvenile what appeared to be a Molotov cocktail" (document at right). The DPD then arrested this man and another man for inciting a riot. Based on the Kercheval reports in the newspapers and evidence offered in the subsequent conspiracy proceedings, it is clear that the two men arrested on the evening of August 11 were Alvin Harrison and Thomas Abston. But--unlike General Baker and other radicals previously discussed as dangerous militants--Detective McCoy declined to name these two men in his congressional testimony.

However, McCoy then told an elaborate story (below right) about how, in a 1965 meeting of ACME, one of the unnamed men charged with passing the Molotov cocktail to juveniles gave a speech urging the crowd to "get black clothes and guns, and fight the police. They are our enemies." (This account clearly came from the DPD's undercover agent inside ACME). Then, on August 9, the first day of Kercheval, the "same person" urged AAYM members to "break stores and windows." (This person would be Harrison, based on the pretrial testimony by the two African American boys). Then another unnamed man allegdly said, "Brothers, go home and get your guns and bring them back here. We'll throw rocks to break the windows and when the police arrive, we'll shoot them." (According to pretrial testimony, this was allegedly Moses Wedlow). But despite all this evidence, none of these unnamed men had been convicted, and charges against at least one of them had been dismissed by the Wayne County judge.

The two men whom Detective McCoy declined to name--who allegedly urged ACME and AAYM members, and black youth in the Kercheval area, to attack the police--are Alvin Harrison and either Thomas Abston or Moses Wedlow. Why not name them, in a hearing dedicated to exposing the role of black militants in inciting urban riots, in a hearing where McCoy gladly named other black radicals in Detroit? The logical conclusion is that Alvin Harrison, and probably also one of the other AAYM men, were the sources for the DPD knowledge and 'proof' that leaders of AAYM-ACME were inciting violence, justifying the law enforcement crackdown. They were the ones inciting violence, and they were also the undercover spies.

Later in the hearing, the confused congressmen recalled Detective McCoy and asked him specifically about Alvin Harrison, whom he had not named in his testimony about advocating violence against police, but had briefly identified as the head of AAYM, and demanded to know why Harrison was not incarcerated. McCoy responded that Harrison, born in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1940, moved to Detroit from New York City in May 1965, quickly became an ACME and AAYM leader in the campaign against police brutality, and began to give "racist" speeches about Black Power. One of the congressmen, clearly angry about the lack of speedy justice, asked why Harrison had not been convicted at trial on the inciting to riot charge, given the level of detail about AAYM's criminal conspiracy in McCoy's previous testimony. The following exchange ensued:

There are only three plausible explanations for why Detective McCoy of the DPD's undercover surveillance unit told a story about an unnamed man, presumably Alvin Harrison, inciting a riot and urging black activists to shoot the police; gave detailed accounts from DPD surveillance records with direct quotations calling for armed resistance over a two-year period by an unnamed ACME-AAYM leader, presumably Harrison, but again declined to name him; and then later named him with extensive knowledge of his life history but asserted that the DPD "cannot tell you why" charges against Harrison were still pending despite the abundance of evidence against him.

The first is that the DPD or its undercover informant fabricated the evidence to justify the law enforcement drive to crush the Afro-American Youth Movement. This is certainly possible, but the unusual sequence of events in the riot conspiracy trial make it improbable that this explanation is sufficient. So does the subsequent emergence of Harrison as a respectable black activist who, immediately after facing conspiracy charges for advocating violence again the police, went to work for the city's antipoverty program in 1967 and then was named by Cavanagh to the New Detroit Committee task force, even as AAYM disintegrated.

The second possible explanation is that Harrison was a genuine radical who decided to turn on his AAYM colleagues after his arrest during the Kercheval Incident, or possibly after a previous DPD arrest, and cooperated with the police and prosecutors by providing evidence against his friends and allies. This would explain the belated plea deal in March 1969, when Harrison received a suspended sentence on reduced charges, without appearing in person at the proceeding, and with the highly unusual involvement of the DPD's Special Investigation Bureau in negotiating the outcome. This scenario is less plausible because the criminal justice system in Detroit kept secret the identity of the man or men inside AAYM who testified with firsthand knowledge, which is not generally how criminal proceedings operate for defendants who turn state's evidence, but is the sort of exception a judge would and did allow for an undercover FBI informant. Under this scenario, one of the other AAYM men arrested alongside Harrison would have had to be the embedded FBI/DPD spy. (It is worth recalling that a judge dismissed the charges against Thomas Abston after the pretrial hearing in August 1966, and that Detective McCoy also declined to name Abston in his congressional testimony).

The third, most likely, explanation is that Harrison was the main FBI spy, the undercover agent provocateur for the DPD's Demonstration Detail/Special Investigation Bureau, who urged (or at least secretly claimed that someone had urged) violent attacks on law enforcement so that the Detroit Police Department would have a legal pretext to surveill ACME and AAYM for their civil rights activities, and have a legal pretext for making mass arrests to subdue the Kercheval "Mini-Riot" before it spiraled out of control, and have a legal pretext to crush ACME-AAYM and its leadership of the most effective grassroots anti-police brutality movement in the city. This conclusion does not preclude the existence of one or more additional undercover FBI/DPD informants.

Alleging that a Black Power activist who offered powerful critiques of police brutality and racial inequality was actually an undercover FBI/DPD agent is a difficult move to make both historically and ethically. The fact that Harrison took a plea deal almost three years later, in March 1969, does raise some doubts, because why wouldn't the prosecutor just drop the charges against an undercover agent? One admittedly speculative theory is that, because defense attorney Milton Henry had close ties to Detroit's black radical community, the prosecutor and the DPD Special Investigation Bureau tied up loose strings by having "Alvin Harrison" take a no-jail time plea bargain in abstentia. There are also other men from AAYM who were arrested during the Kercheval Incident, accused of advocating violence, and then had charges dismissed, and one or more of them could have been undercover FBI and/or DPD operatives. The Policing and Social Justice HistoryLab certainly welcomes contradictory evidence and will correct the record and apologize if this interpretation that the preponderance of archival evidence points to Harrison is refuted. But in addition to the arguments presented above, there are other pieces of archival evidence and also archival silences that speak volumes to support this interpretation.

- Frank Joyce, the first ACME director, responded unprompted in an interview with our project that he and also several African American activists who worked with Harrison in ACME and/or AAYM and still keep in touch believe that, “as we’ve looked back on that whole experience, probably Al Harrison is our number one suspect for being an agent.”

- In the mid-to-late 1960s, the FBI often recruited African American agent provocateurs who had backgrounds in the military and sent them to new cities to join emerging groups as undercover spies. Harrison was 25 yars old when he joined ACME in 1965, immediately after moving to the city, if McCoy's biographical account is to be believed, which fits the age profile of an ex-military agent. And as Frank Joyce recounted, Harrison "sort of showed up out of nowhere” in the spring of 1965, and "we did notice he was somehow becoming the spokesperson." It was “strange when he showed up and strange when he disappeared,” just as suddenly.

- Alvin Harrison's name does not appear in any of the DPD "Red Squad" documents and FBI surveillance files of Detroit activists that our project has reviewed. Although this search is not and cannot be exhaustive, it was standard operating procedure for the FBI and other government surveillance units to redact or omit the names of their undercover agents, or to use code numbers instead of names, in these reports.

- General Baker (now deceased), the black radical from the League of Revolutionary Black Workers, who was arrested during Kercheval after the FBI informant's tip from inside AAYM headquarters, often stated that he suspected Alvin Harrison of being an undercover police spy, according to Baker's biographer, Professor David Goldberg of Wayne State University.

- Harrison joined mainstream civil rights leaders in a meeting with Mayor Cavanagh to discuss the Kercheval Incident in August 1966, while his trial on riot incitement charges was pending, which is unusual to say the least. He was the only black militant leader invited, accompanying a group whose main request was for the city to hire more African American police officers.

- Harrison was also the only black militant leader invited to be on the New Detroit Committee, established by Cavanagh to rebuld Detroit and repair race relations after the 1967 Uprising. This also makes little sense, given the DPD's alleged evidence that he had incited violence during the Kercheval Incident, and the fact that he was still under indictment and his trial was still pending, unless the Cavanagh administration realized Harrison was someone who could be trusted.

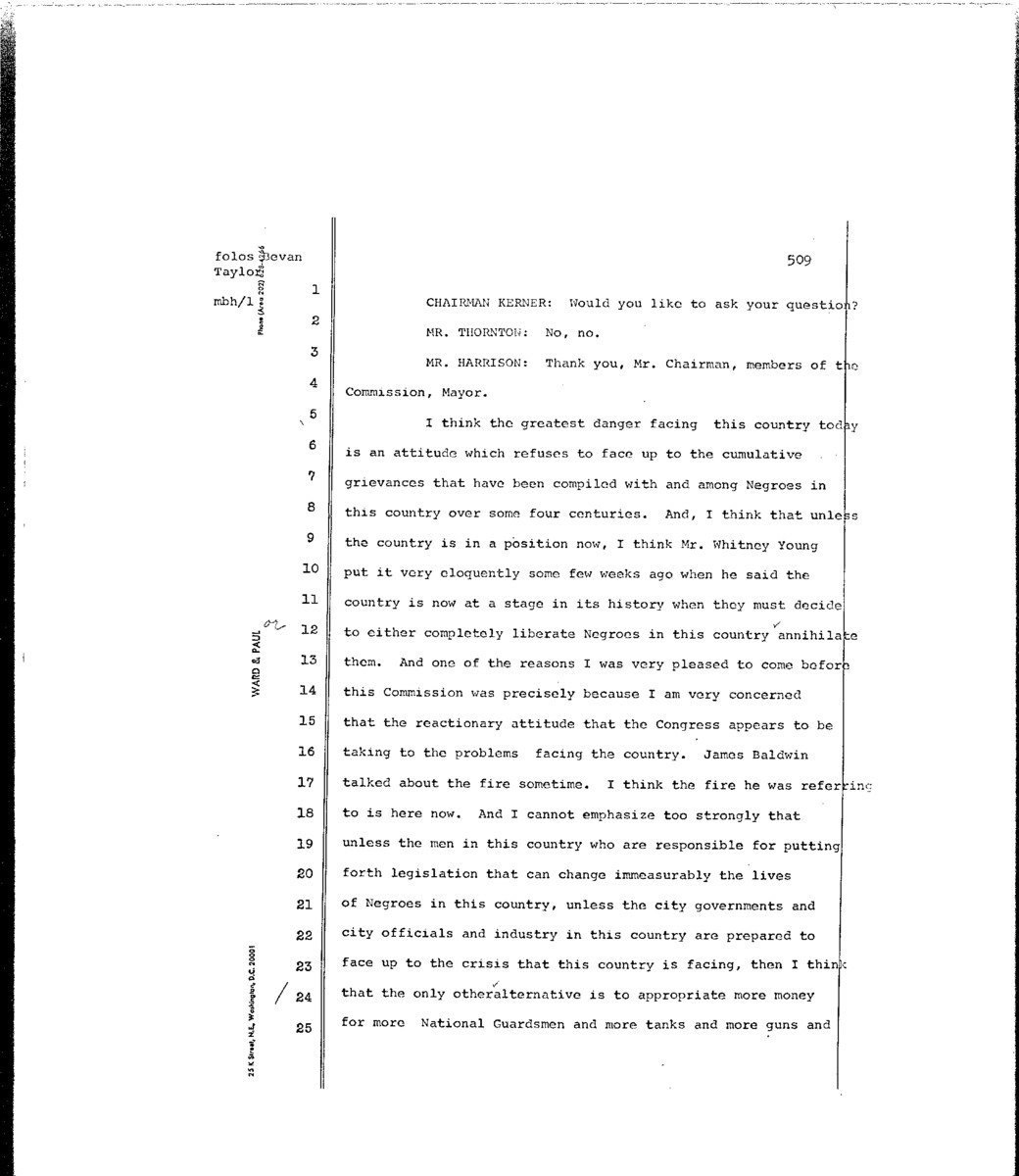

- In mid-August 1967, Harrison also traveled with Mayor Cavanagh and a delegation of establishment leaders from Detroit, including Police Commissioner Ray Girardin, to testify to the Kerner Commission about the causes of the riot/rebellion two weeks earlier. His trial on riot incitement charges was supposed to happen that same month. He was the only civil rights activist included in the delegation and was identified as the citizen representative for Neighborhood Legal Services, a War on Poverty program. Harrison's testimony to the Kerner Commission (see gallery below) offered a powerful indictment of the nation's responsibility for creating explosive racial conditions in the inner city. He also lavishly praised Cavanagh's leadership of Detroit, which is, again, an unusual stance to take for a black power activist who had denounced the mayor and DPD as racist oppressors after the Kercheval Incident and who at that time still faced pending conspiracy charges for inciting riot.

- Harrison, according to a white Catholic social worker who collaborated with him on the city's antipoverty initiative in 1967, "has an airline ticket for Paris that he renews every day." This man, Anthony Locricchio, told this story (below) in December 1967 to investigators for the Kerner Commission, during its fieldwork to determine the causes of the Detroit Uprising. Locricchio also stated that Harrison was not really as politically radical as he seemed. If this story is true, how and why would a civil rights activist have an overseas ticket always ready to use, unless a government agency was making that possible, presumably in fear that his life would be in danger if his identity were exposed?

- Harrison disappeared from Detroit, and disappears almost completely from archives and newspaper databases, in October 1967, with announcement of his membership on the New Detroit Committee, except for the brief notation in March 1969 that he lived in Cleveland and took a plea deal that resulted in no punishment. It is, of course, possible that his name was not even Alvin Harrison.

In the end, whether or not Alvin Harrison or someone else was the undercover FBI/DPD informant is less important than the definitive evidence that the Detroit Police Department utilized one or more FBI spies who had infiltrated ACME and AAYM. These undercover agents or police informants allowed the Detroit Police Department to frame these direct-action protest organizations as advocates of violence against law enforcement, in order to justify the Kercheval crackdown and the conspiracy charges that effectively ended ACME-AAYM as a potent community-based movement against police violence and oppression of African Americans in Detroit.

Sources:

Detroit News

Detroit Free Press

[Riot conspiracy trial in Detroit Free Press, Aug. 15-25, Sept. 7, 1966]

Fifth Estate

Michigan Chronicle

Francis A. Kornegay Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

Jerome Cavanagh Papers, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

“Riots, Civil and Criminal Disorders: Part 6,” Hearings before the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, U.S. Senate,” March 21-22, 1968 (Washington: GPO, 1968)

Sidney Fine, Violence in the Model City: The Cavanagh Administration, Race Relations, and the Detroit Riot of 1967 (2007)

Heather Ann Thompson, Whose Detroit? Politics, Labor, and Race in a Modern American City (2017)