IN FOCUS: Commissioner Ray Girardin

Climbing the Ranks

Ray Girardin was a crime reporter before his tenure with the city of Detroit. While characterized as a Cavanagh liberal, he reported crime stories in a way that applauded law enforcement efforts. Girardin’s almost relentless support of the DPD began long before he became police commissioner. In 1962, shortly after Cavanagh was elected mayor, he appointed Girardin as his administrative assistant. Then, after George Edwards resigned in December 1963, Cavanagh named Girardin as police commissioner. Girardin and Cavanagh agreed on the goals of linking the wars on poverty and crime, and the DPD's presence in Detroit's poor black neighborhoods increased significantly under the leadership of both men. Cavanagh’s support for Girardin never wavered, giving the police commissioner a considerable amount of freedom in the operation of the Detroit Police Department.

Girardin shared key liberal philosophies with Cavanagh and President Johnson. For example, he viewed poverty as a direct cause of criminal behavior. Girardin also praised urban renewal programs, which he hailed as “directly tie[d] to economic development.” Employment was central to his urban renewal ideals, as was the eradication of juvenile delinquency. Girardin was integral in the launching of Community Action for Detroit Youth (CADY), in hopes of quelling displays of "deviant" behavior among youth by targeting young black males in poor neighborhoods. Girardin envisioned urban renewal as part of a vast mission to curb criminal activity in impoverished communities. He believed that decreasing unemployment and providing youth supervision could reduce poverty and thus crime in Detroit. To fight juvenile crime, Girardin promised to put more police officers on the streets and touted his program that brought 90 officers directly into public schools.

The gallery below contains a 1964 speech by Commissioner Girardin on urban renewal, juvenile delinquency, and police focus on juvenile crime through programs in schools. Double-click the first document for the full speech.

Defending DPD Autonomy

Girardin became police commissioner soon after the controversial killing of Cynthia Scott and at a time when civil rights organizations were demanding police reform in Detroit, including a civilian review board to investigate allegations of police brutality and misconduct. Girardin formally took a position resisting “any major policy changes,” according to the Detroit Free Press. Girardin resisted civil rights demands for civilian oversight, increased educational requirements for new officers, and other changes to restrain racial discrimination by DPD officers. In short, Girardin strongly opposed any direct civilian input on DPD procedures and internal investigations.

In December 1964, Girardin met with the NAACP and the Police-Community Relations Subcommittee of the Detroit Commission on Community Relations (document on right). The civil rights and religious leaders at the meeting asked for more transparency regarding how the DPD investigated complaints about police brutality and harassment--specifically mentioning the beating of Barbara Jackson and oppression of young activists in the Adult Community Movement for Equality. The civil rights leaders also demanded that the commissioner put a stop to the habit of precinct-level officers of counter-charging civilians who filed complaints about police misconduct and brutality in order to coerce them into dropping the case (see p. 4 of the document). Girardin promised that this policy was no more (although enforcing such a prohibition was almost impossible) and also pledged that the new Citizen Complaint Bureau woud investigate all matters fairly and share its records with the NAACP. However, the “air of secrecy about their investigations” that Girardin said he would eliminate persisted throughout his time as police commissioner.

Commissioner Girardin received other reform recommendations from members of Detroit’s Common Council. Councilor Mel Ravitz, a white progressive and ally of civil rights groups, wrote to Girardin in January 1964, shortly after his appointment. Ravitz called for major policy and cultural changes in the DPD, including pay raises for officers, increased community-relations training, and updating the training material for new recruits. Girardin did bring more "human relations" training into the Detroit Police Department, as part of the larger effort to professionalize police officers and improve their racial prejudice toward nonwhite and poor communities. But Girardin and Mayor Cavanagh continued to resist the most important reform--civilian oversight of investigations into police brutality and misconduct.

Girardin was a vehement defender of the actions of his officers. He asked for community support of the DPD's crime-fighting mission during controversies that followed egregious civil rights violations by officers on the street. Additionally, he blamed the Detroit community for a lack of professionalism among officers, asking them to send more qualified recruits. Girardin often warned that too much attention to police brutality would negatively affect the performance and morale of law enforcement duties.

"Total Enforcement of the Law"

In this 1965 speech about police misconduct and wrongful arrests (right), Commissioner Girardin assured officers that should a lawsuit be filed against them, the DPD would support them wholeheartedly with legal representation. The DPD had a long history of making illegal investigative arrests, without a warrant or probable cause. Iin the draft of this speech. Girardin initially typed that the DPD would defend officers "if you make an illegal arrest," before crossing out that line and replacing it with an arrest "that doesn't hopld up." In this way, Girardin accepted and even encouraged misconduct from his officers. Eventually, the city of Detroit resolved this problem not by curtailing illegal investigative arrests but by formalizing discretionary policing through ordinances that gave the police authority to arrest people for vague crimes such as loitering.

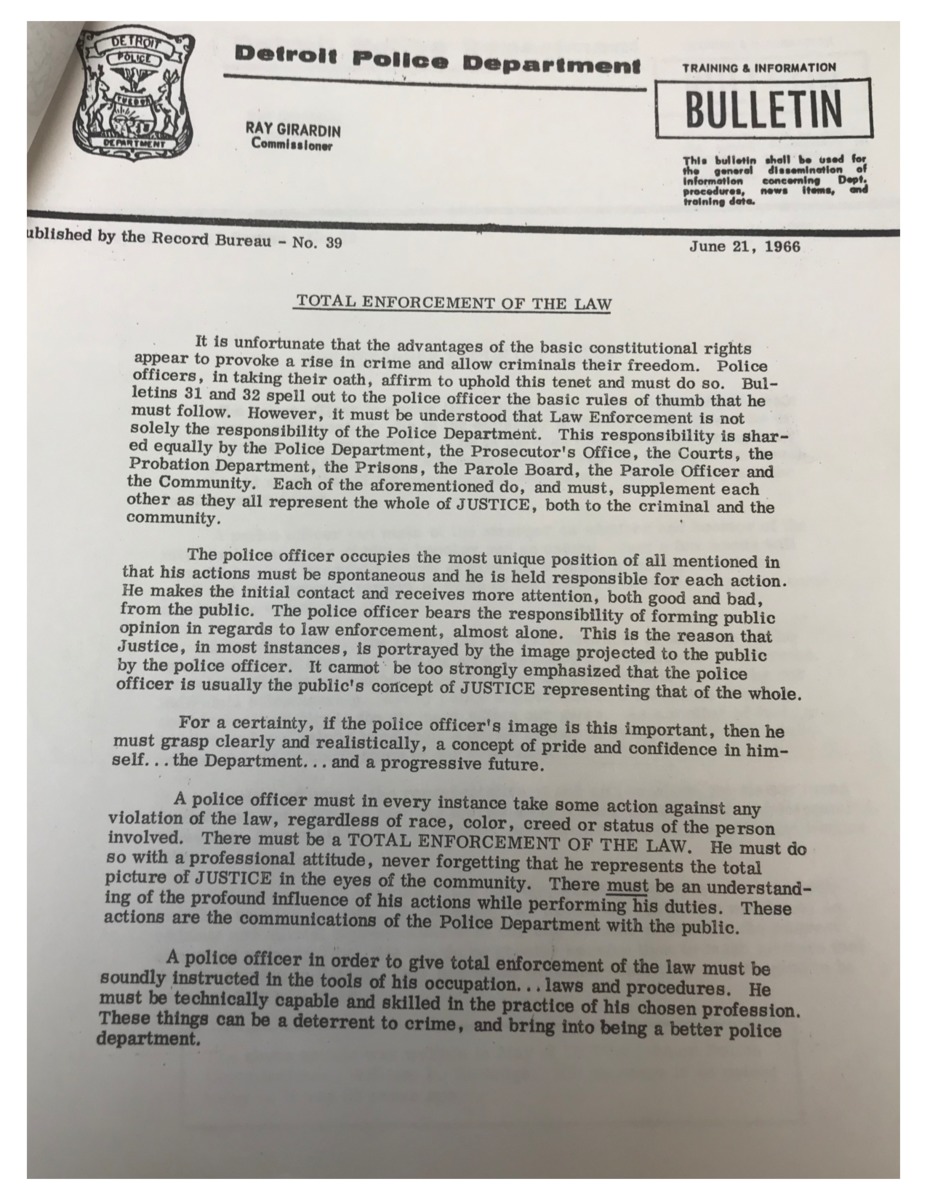

Girardin’s view of enforcing the law was unrelenting. In a 1966 bulletin to DPD officers (below), Girardin reinforced the importance of image when enforcing the law and emphasized that the police officer needed to establish the presence of justice within a community. Girardin also stressed the importance of professionalism in the workplace and called on all officers to enforce the law without bias against any racial group.

In the same bulletin, the DPD defined the parameters for entering private property, listing standard notions such as the requirement of a search warrant and protecting someone inside from imminent danger. Yet, the last point encourages any decision by an officer who “can otherwise legally justify his action.” Given Girardin’s previously mentioned position on defending officers who commited misconduct and made "illegal" arrests, this provision exemplifies the ambiguity and discretion in operating procedure under Girardin's leadership.

The bulletin goes on to outline the acceptable reasons for arresting a citizen. Among those reasons are: the officer holds an arrest warrant, a felony or misdemeanor is committed in view of an officer, or if there is reasonable suspicion of a felony. However, the bulletin also adds various clauses containing the phrase “reasonable suspicion.” This phrase endows officers with a tremendous amount of discretion when patrolling the streets and is at the heart of how police operated to criminalize poor black neighborhoods in Detroit, and not just to fight crime.

Finally, the bulletin instructed officers to respect the constitutional rights of all citizens and to "use physical force only when the exercise of persuasion, advice and warning is found to be insufficient to obtain cooperation and then only that amount necessary to effect the arrest."

Sources:

Detroit Commission on Community Relations / Human Rights Department Records, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

Detroit News, April 12, 1963

Mel Ravitz Papers, Reuther Library, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

Michigan Chronicle, February 1, 1964

Ray Girardin Papers, Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library

Detroit Urban League Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan