Civil Rights: Countering Crash

The crash program outraged African Americans throughout Detroit and ultimately led to the downfall of Mayor Louis Miriani and Commissioner Herbert Hart, as black voters punished them in the fall 1961 election in favor of a white liberal mayor who promised police reform.

NAACP Coalition Denounces Crash

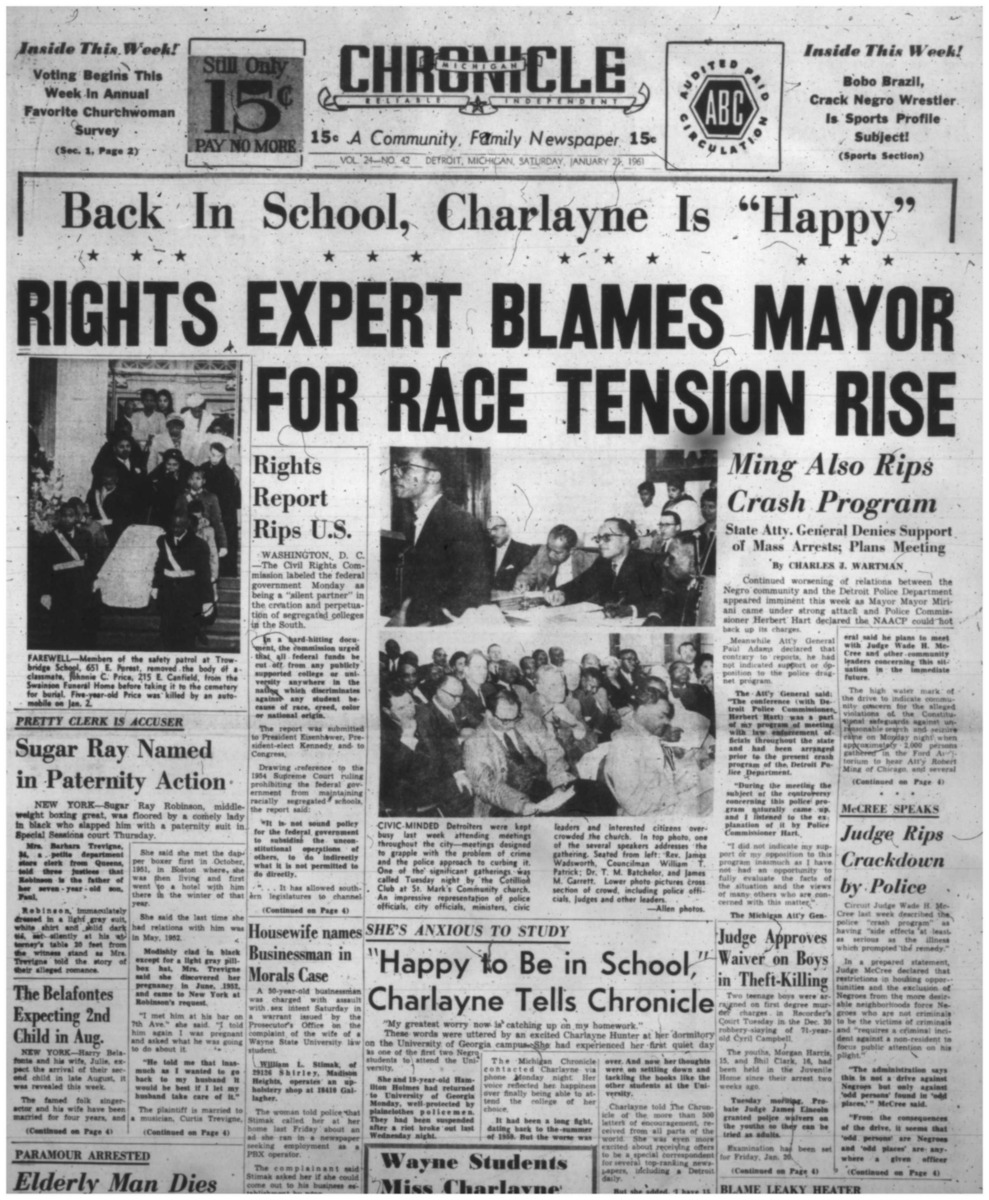

In late December 1960, after the most intense week of the manhunt, the NAACP called a mass meeting of 75 civil rights, religious, labor, and civic organizations to devise a strategy in response to crash. Most liberal and progressive groups in Detroit participated, including the ACLU, the United Auto Workers, and the American Jewish Congress. The delegates at the meeting strongly condemned the tactics of the Detroit Police Department and accused the mainstream newspapers of inflaming racial tensions. The coalition demanded a meeting with the mayor and also reiterated the call for a civilian review board to oversee the police department and investigate allegations of brutality and misconduct.

The NAACP-led coalition released a lengthy public statement (full text on right) that called on the city to "eradicate the economic and social conditions that breed crime," which meant poverty and racial discrimination, rejected the view that the crime problem was the fault of any particular race. The statement also demanded that citizens obey the law and and that law enforcment respect the constitutional rights of the citizenry. And the statement emphasized:

Mayor Miriani rejected the NAACP's charges and rebuked the coalition for implying that the DPD was discriminating based on race or violating the constitutional rights of any citizens. The mayor Miriani and DPD officials, with the backing of the white newspapers, insisted that the crime crackdown could not be biased because the suspects were "Negro males." They also claimed that the police street sweeps were carefully implemented. Miriani explained that police officers "were specifically instructed there was to be no indiscriminate stopping and questioning of people, but to alert themselves to those persons who were in odd places at odd hours without any reasonable explanation." Given that the DPD boasted that its crackdown had led to the arrest and detention of 1,500 suspects and had stopped and searched 150,000 black men on the street, this pledge did not convince many people in the black community or in the larger coalition of liberal and civil liberties organizations.

Black Ministers Condemn Crash

On January 10, the Interdenominational Ministers Alliance of Metropolitan Detroit, a group of African American pastors, held its own mass meeting and strongly criticized the DPD's crash program. Rev. Charles A. Hill promised that "if necessary, we will go into legal fields to prevent public officers from violating the law and to protect those who are the victims." The ministers also denounced the "race baiting policy of daily newspapers." The ministers released this statement:

On January 11, Mayor Miriani responded by publicly commending the Detroit Police Department for handling "the present emergency with firmness and dignity" and concluded: "public safety has been protected without sacrificing the principle of civil rights." He also announced the end of the crash program, saying that it had accomplished the objective of making Detroit safe again.

Crash as Racial Dragnet

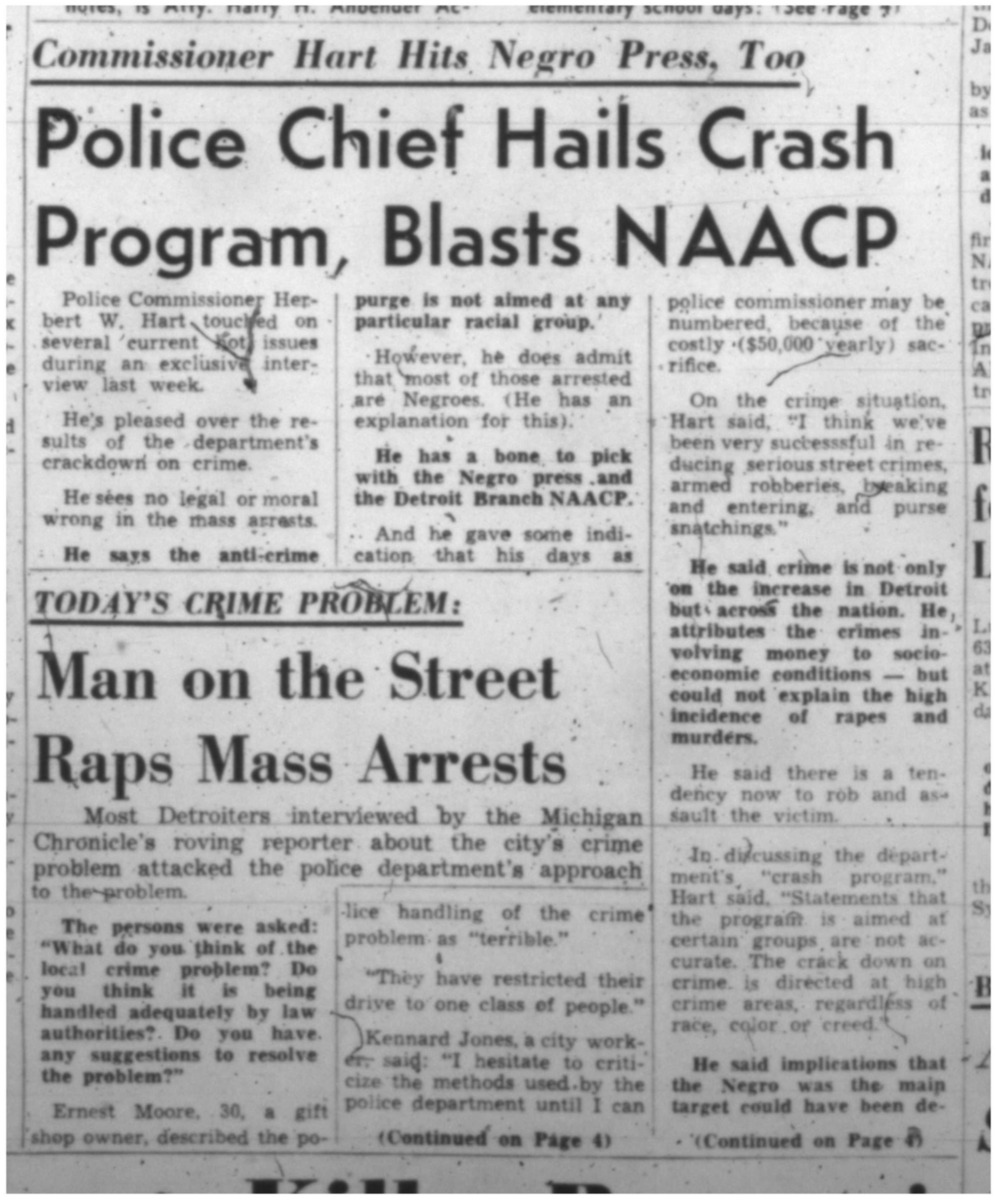

The city's announcement that the crash program had ended did not stop the outpouring of criticism from African American leaders and civil rights groups. The Michigan Chronicle, the city's black weekly, also continued to cover crash with banner headlines throughout January 1960 (above gallery).

Judge Wade McCree, a circuit court judge and one of the most respected black officials in the criminal justice system, released a public letter about the crash program on January 9 (right). He began by praising the goal of crime control but then warned that the "indiscriminate arrest of Negro persons" would harm the cause of law enforcement by alienating "many Negro citizens" from the DPD. McCree pointed out that the law-abiding majority of black citizens could not live in the "better communities" because of housing segregation, and so they had to live in or near the high-crime areas and therefore suffer the criminalization and racial profiling of the police. He pointed out:

McCree also directly challenged the mayor's insistence that the DPD only targeted "odd persons" in "odd places" and instead stated that the crash program had segregationist intent: "From the consequences of the drive, it seems that 'odd persons' are Negroes and 'odd places' are anywhere a given officer thinks a Negro should not be." He also warned that black citizens might well conclude from the manhunt that the DPD "has as one of its missions the intimidation and oppression of persons of color."

Superintendent Louis Berg, the police official in charge of the crash program, responded to McCree by stating that the DPD respected the constitutional rights of all citizens and that the targeted focus on black men fit the description of the suspects.

Demands for Police Reform and a Modest Compromise

The Michigan Chronicle covered the civil rights crusade extensively, with front-page headlines and many stories (see gallery above). The African American newspaper reported at length on the "illegal search" of NAACP leader Arthur Johnson, accosted in his car while on the way to a meeting, which the mainstream white newspapers barely mentioned. The Chronicle also asked regular black men "on the street" for their views of the crackdown, which drew widespread criticism. In sum, the African American paper covered the crash program as a violation of civil rights that had galvanized the black community rather than a crime control initiative.

Throughout January and beyond, the NAACP and other civil rights groups continued to demand major changes to police tactics on the street, as well as the hiring of more black officers and a civilian review board to monitor police brutality. The mayor and DPD flatly refused to consider a review board and claimed that they were "constantly asking for qualified Negro officers." (Below 4 percent of police officers in the city were African American, and the ratio of black-to-white officers decreased in the early 1960s).

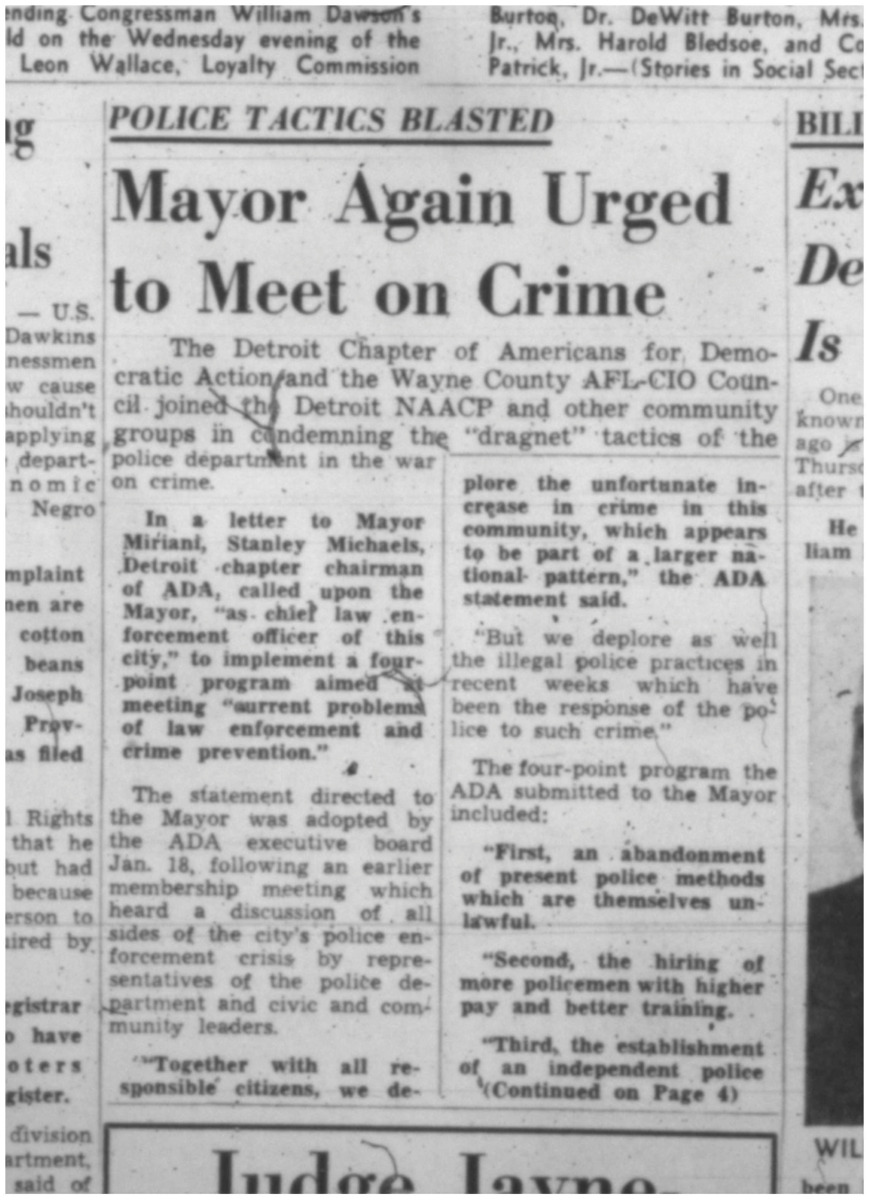

In February, a coalition of 75 civic and civil rights organizations launched another concerned campaign for police reform, including civilian oversight. The Detroit chapter of Americans for Democratic Action submitted a four-point program to Mayor Miriani outlining their demands:

- "First, an abandonment of the present police methods which are themselves unlawful."

- "Second, the hiring of more policemen with higher pay and better training."

- "Third, the establishment of an independent police public review board, which can reassure the community of impartial evaluation of citizen complaints against police, for the protection of both citizens and police."

- "Fourth, a reshaping of the Commission on Community Relations, which at this time of crisis and need has been paralyzed by apparent subservience to other city agency heads who dominate its machinery. This commission must have greater public participation, greater independence and greater authority in order to be effective."

The outcome of this pressure campaign was a modest compromise. Mayor Miriani again refused to consider an independent civilian oversight commission, but he did agree to create a Community Relations Bureau inside the DPD. This was a very limited step, as Commissioner Hart soon made clear, since the Community Relations Bureau had no independent investigative authority. The NAACP labeled this reform a public relations maneuver.

Miriani also agreed to reorganize the existing Detroit Commission on Community Relations (DCCR) and create a subcommittee that would be able to investigate complaints against the police department. This subcommittee, however, lacked the power to subpoena testimony and to implement any disciplinary action. Instead, the DCCR could write reports to the mayor and police commissioner, who retained the power to accept or reject the findings and to make all decisions regarding discipline. Not surprisingly, very little changed.

The more consequential reforms caused by the civil rights mobilization against the crash program came about through electoral politics. In November 1961, African American voters rallied behind white liberal Jerrome Cavanagh and his promise to reform the DPD. Mayor Louis Mirani, a conservative Republican, lost in a major upset to a young white Democrat who endorsed racial equality and pledged a new beginning in Detroit.

Sources

Detroit News, Jan. 1961 articles

Detroit Free Press, Jan. 1961 articles

Michigan Chronicle, January 7-February 18, 1961

American Civil Liberties Union of Michigan/Metropolitan Detroit Branch Collection, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University