Police Shooting of Teenagers

During 1962-1963, protests erupted after two episodes in which Detroit police officers shot and killed teenagers, one African American and one white, who were unarmed and fleeing apprehension. DPD Commissioner George Edwards and Wayne County Prosecutor Samuel Olsen exonerated the officers involved in both of the cases.

Overall DPD officers shot and killed seven male teenagers between 1957 and 1963, and a Michigan State Police trooper shot and killed an eighth on the streets of Detroit. Each of these cases is detailed on the previous "Mapping Police Killings" page. All but one of the teenagers were unarmed, and none of the juveniles had weapons. Three, all Black males, were younger than 16. All of them were fleeing the scene of low-level property crimes or traffic violations, often after "joyriding" in a stolen car, except for one 19-year-old who committed an armed robbery. In all of the other cases, the teenage males were shot from behind and posed no threat to the officer when killed. They lost their lives for alleged offenses that if adjudicated through the legal process would have brought, at most, commitment to a juvenile detention facility or a short jail term. In fact, there is strong evidence that the two youth profiled on this page fled from police because they did not want to be forced to return to juvenile detention.

David Carson, shot and killed by two white officers in May 1962, was a 14-year-old African American male. Kenneth Evans, shot and killed by two white officers in July 1963, was an 18-year-old white male. Both teenagers were in stolen cars and led the police on high-speed chases, and then were shot from behind after they fled on foot. Both teenagers also were "juvenile delinquents" who had been incarcerated for previous offenses, although the officers chasing them did not know their identities. Their juvenile records, however, played a significant role in the media coverage, which criminalized them as "incorrigible youth," as did the DPD and the prosecutor in declaring their homicides to be legal and proper.

In each case, the DPD and the prosecutor defined the teenagers as "fleeing felons," based on automobile theft and reckless driving, in order to declare the shootings to be "justifiable homicides." The DPD manual stated that officers should not fire on suspects who were "running away to escape arrest except in extreme cases," and only if "the perpetrator cannot be apprehended by any other means." As the evidence makes clear, the police certainly could have apprehended both David Carson and Kenneth Evans by "other means" than an extrajudicial execution in the streets. Yet in both cases, the DPD and the prosecutor used the discretionary language of "extreme cases" to define the teenagers as felons and to justify their homicides.

The Killing of David Carson (May 13, 1962)

On May 13, 1962, at 11 p.m., David Carson was shot and killed by Officers Edward Zupancic and Peter Hall of the Petoskey Precinct. The two white officers encountered Carson when "he ran a red light at Euclid and Lawton." The officers began to chase after the vehicle, and Carson ran five lights before he crashed into a guardrail on the entrance ramp to the Lodge Expressway. Carson then kept fleeing on foot. Officers Zupancic and Hall said that they ordered Carson to halt and then each fired multiple warning shots. As Carson continued to run, with his back to the officers, he was killed with one bullet to the head, fired by Officer Zupancic. David Carson was pronounced dead at Receiving Hospital.

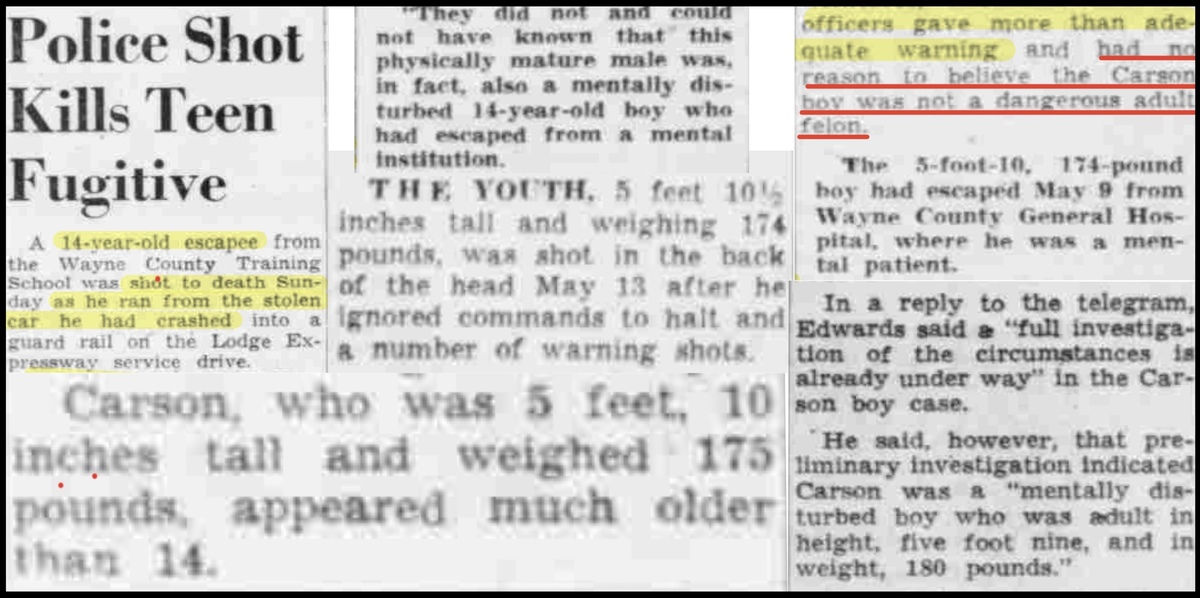

David Carson was a 14-year-old African American male. He suffered from mental illness, but the DPD and the Detroit newspapers did not report the story that way. Instead, the first newspaper account of his death labeled Carson a "teen fugitive" and "14-year-old escapee from the Wayne County Training School" (a juvenile incarceration center), before even mentioning his name. The newspaper coverage, based on the police reports, also repeatedly emphasized that Carson's physical appearance, at 5'10'' and 175 pounds, made him appear to be an adult (see graphic below). From the media, it seemed that David Carson's true crime was being an unusually large 14-year-old, and this description also helped enable his killers to escape criminal prosecution.

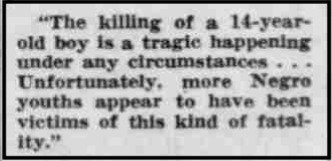

The NAACP immediately demanded an investigation and pointed out that police killings of teenagers who were unarmed and fleeing had a "race aspect" and mainly happened to "Negro youths" (right). The NAACP also called on DPD Commissioner George Edwards to undertake a "complete reappraisal" of the aggressive methods and deadly force that police officers used when dealing with fleeing suspects, especially teenagers.

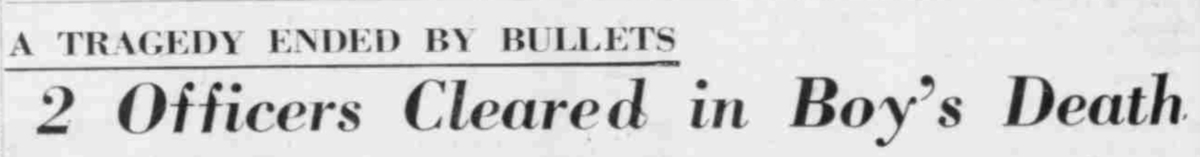

On May 22, Wayne County Prosecutor Samuel Olsen ruled the homicide of David Carson to be justified, as he always did whenever the police killed anyone "in the line of duty" during his time in office. Olsen publicly announced that he "took the youth's size into consideration."

Commissioner Edwards promised an internal DPD investigation but also predetermined its outcome by responding to the NAACP that David Carson was gulty of two felonies, automobile theft and "felonious driving," and that he was a "mentally disturbed boy who was adult in height, five foot nine, and in weight, 180 pounds."

On May 25, Commissioner Edwards formally exonerated the two police officers. He cited their reasonable belief that David Carson was a "dangerous adult felon" and said they had no way to know that he was a "mentally disturbed 14-year-old boy." The commissioner also emphasized that David Carson had been confined in juvenile detention centers since the age of 12 and that he had previously committed the offenses of automobile theft, larceny, and carrying a concealed weapon. (This information had no legal relevance to the question of whether the officers should have killed someone in a chase scenario for the crime of reckless driving and served only to criminalize an African American teenager and justify his extrajudicial execution without due process). Edwards concluded:

The DPD commissioner, in his fifth month on the job as a liberal reformer, therefore justified the use of excessive force to kill a child who was speeding and driving recklessly in a car that the officers had no way to know was stolen. The officers could have pursued David Carson on foot and arrested him, which would have led to proceedings that could have established his guilt or innocence and evaluated his criminal capacity, but they chose to end his life. After first firing warning shots at his feet, they then killed him with a bullet to the back of the head, which did not appear to conform to the DPD Manual's restriction of the use of deadly force to extreme circumstances. Instead of enforcing the policy as spelled out in the DPD Manual, Commissioner Edwards justified the police use of deadly force against an unarmed civilian through the "fleeing felon" loophole and through the 14-year-old's legally irrelevant juvenile record and body size. Edwards, who had recently tightened the use of force guidelines, might have personally wished that his police officers had not fired their weapons at an unarmed teenager, but when they did he closed ranks and protected them. It would not be the last time.

The Killing of Kenneth Evans (July 12, 1963)

Kenneth Evans was white, and four years older than David Carson, but his story is eerily similar. Both teenagers fled from the police on foot after crashing stolen cars, and both did so because they feared being sent back to juvenile detention. Both teenagers were shot and killed from behind, although the actions of the officers in the Kenneth Evans case seem more premeditated, and arguably a clearer case of murder, than in the more rapid-fire police killing of David Carson, because of the lengthy time that lapsed between Evan's alleged crime and his death.

On July 12, 1963, Kenneth Evans was shot and killed by Patrolman Paul Funk and Patrolman Charles Archibald of the Detroit Police Department. Around 7 p.m., the two officers spotted Evans in an alleyway and allegedly yelled at him to halt before shooting him twice, once in the back and once in the shoulder, as he ran away.

Officers from the Vernor Station precinct had been searching for Kenneth Evans and three other teenagers, including his 17-year-old brother James, since 9:30 a.m. that morning, when they were reported speeding and driving recklessly. Late that Friday afternoon, police officers found the stolen car that the teenagers had been joyriding in, parked on the street near the home of Kenneth and James Evans. Several officers then entered the Evans home to apprehend the youth, and Kenneth Evans ran out the back door. The two officers, Paul Funk and Charles Archibald, found Kenneth Evans hiding near his home and shot him dead.

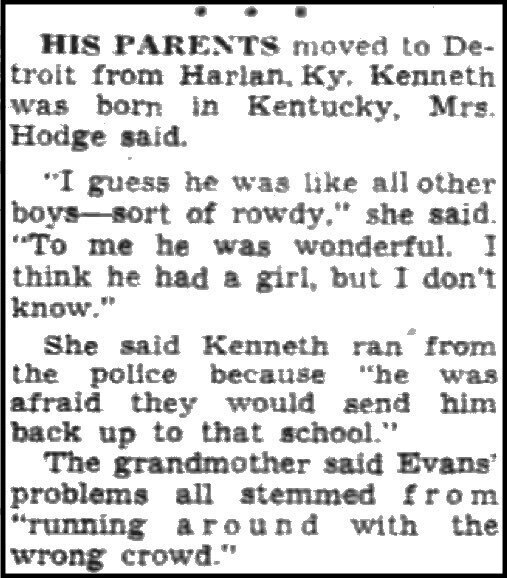

The mainstream newspapers portrayed the white teenager Kenneth Evans and his grieving family quite differently from African American teenager David Carson, whose family they did not bother to interview and whose troubles with the law they did not try to explain. Kenneth Evans's death was presented as a community tragedy, while David Carson's was an unfortunate sequence of events for which no officer could be blamed. The Detroit Free Press coverage emphasized that the Evans family were migrants from Kentucky, that the father of the boys was dead, that Kenneth had lived with his grandmother from a young age, that he entered the juvenile detention system as a 10-year-old and had been in and out ever since, and that he was unemployed at the time of his death. Kenneth's grandmother said that he was "like all the other boys--sort of rowdy," and had been "running around with the wrong crowd." She also explained that Kenneth had run away from the police because "he was afraid they would send him back" to the juvenile detention center (see right).

Prosecutor Samuel Olsen conducted a perfunctory investigation and exonerated the two police officers, Paul Funk and Charles Archibald, on the same day as the killing. The prosecutor made sure to highlight Kenneth Evans's juvenile record, which included burglary, larceny, and malicious destruction of property. Evans had served multiple stints in juvenile detention centers, including a recent 11-month stay at a vocational prison in Lansing. The police shooting of this juvenile delinquent was, Olsen ruled, "a clear-cut case of justifiable homicide."

But why? Evans was unarmed, and hiding out near his home, and the officers knew where he lived. It strained the facts to classify him a "fleeing felon," based on the automobile theft (joyriding spree) of the four teenagers on a Friday morning ten hours earlier. It seems hard to justify the officers' actions based on DPD policy, which permitted deadly force only in "extreme cases" involving a dangerous "known felon" when apprehension was not possibly "by any other means." Nothing about his prior juvenile record was relevant to the question of whether the officers' actions were legal, despite the prosecutor's deliberate attempt to criminalize Evans and cloud the issue. Based on the facts of the case and the operative laws and policies, the homicide of Kenneth Evans was not legally justifiable, except by a prosecutor and police department determined to uphold all cases of discretionary use of deadly force by DPD officers.

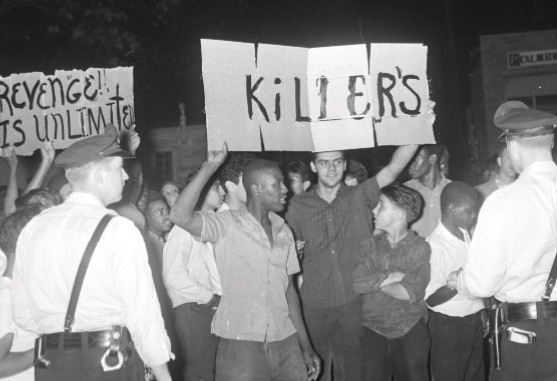

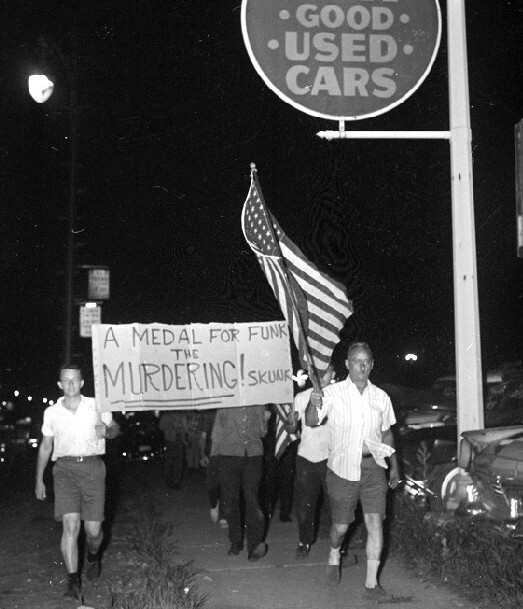

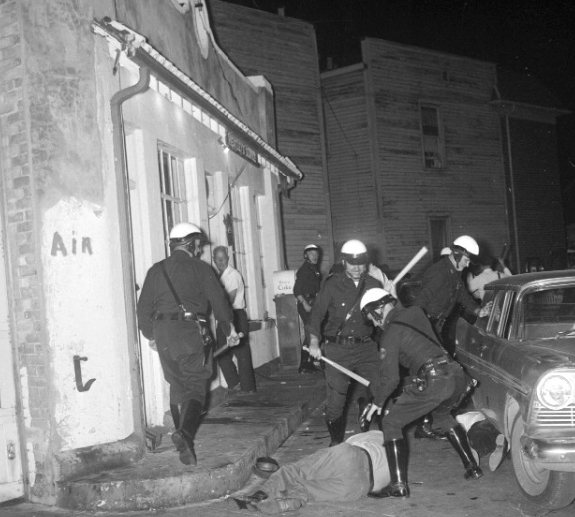

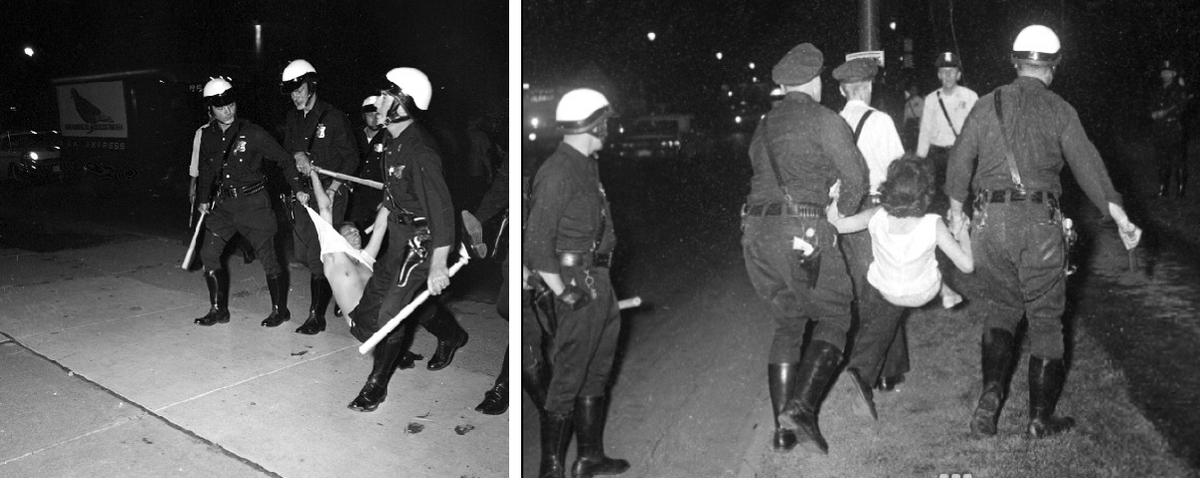

Friends of Kenneth Edwards and his family responded by organizing a march on the Vernor Street precinct station in Southwest Detroit, right after his funeral procession. Between 300 and 400 people took part, mainly residents of the white working-class neighborhood where Evans lived. Some African American youth also joined the protest, holding signs accusing the police of being "Killers" (top of page). The protest turned unruly, with members of the crowd throwing rocks and bottles at the police station, resulting in a dozen arrests. Vernar Station officers brutally beat a number of the marchers (below right). The Detroit Free Press labeled the protesters a "mob of young punks," although the newspaper also questioned why the police officers needed to kill a teenager, even a "young hood," who would not have been hard to find.

The murder of Kenneth Evans took place one week after the police murder of Cynthia Scott, an African American woman shot in the back and then framed by a white police officer. The two cases of deadly force intersected in the political discourse and media coverage in July 1963, when African American groups were holding massive protests demanding the prosecution of the officer who shot Cynthia Scott in the back. The white protesters who knew Kenneth Evans did not get involved in the Cynthia Scott case, or seem to see any connection, but the civil rights and black power groups who mobilized to protest the Cynthia Scott killing did. The ACLU, a coalition of mainstream civil rights organizations, and black power radicals all connected her death to Evans's as evidence of a police department out of control. One black radical publication wrote: "We sympathize with the down trodden white folks too. We don't want any street corner capital punishment--white or black."

DPD commissioner George Edwards reviewed the Kenneth Evans killing and supported the prosecutor's finding that it was justified. The commissioner focused on the "fleeing felon" standard, that Kenneth Evans and his companions were guilty of the "theft of the automobile and the subsequent wild effort to escape in it."

Kenneth Evans was an unemployed white youth from a working-class community whose life was expendable. The Detroit News called him a "garden variety car thief" and an incorrigible delinquent who was "ripening into adult misbehavior and crime." Commissioner Edwards said that this teenager, who went joyriding with his friends and younger brother, and feared being sent back to juvenile detention, had "endangered himself" and taken the risk of being killed by the police because he resisted arrest for his crimes.

While police brutality and unjustified use of deadly force victimized African Americans far more than any other demographic group, poor and working-class white communities also suffered from police violence in less systematic ways, especially the subset of white youth criminalized as delinquents and hoodlums. (See the next section for five more police homicides of white Detroiters between 1964-1966, most in auto theft or fleeing scenarios). When white people did experience police brutality and deadly force, the DPD's internal investigative process and the Wayne County prosecutor almost always denied them justice as well.

Sources:

Detroit Free Press, May 15-16, 23, 26, 1962

Detroit News, May 26, 1962

Detroit Free Press, July 13, 17, 22, 29, 1963

Detroit News, July 22, 25, 1963

Detroit News Photograph Collection, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University