1. Days of the Uprising

This introductory page provides an overview of the main events in the Detroit Uprising from July 23-28, 1967, drawn primarily from the official accounts of the Detroit Police Department, the state of Michigan, and the federal government (including the Kerner Commission investigation). In many parts of this story, the questions of "what happened" and "why it happened" are disputed. The official accounts focus primarily on the criminal and disorderly activities of African American people portrayed as "rioters," "looters," "arsonists," "snipers," and often "crowds." The government sources portray law enforcement actions as necessary and justified, a response to the criminality of Detroit's black population. Therefore, these sources operate to criminalize large sections of the African American community in Detroit, and they deliberately minimize or disguise the violent and disproportionate actions of the state and its role in causing and escalating these events.

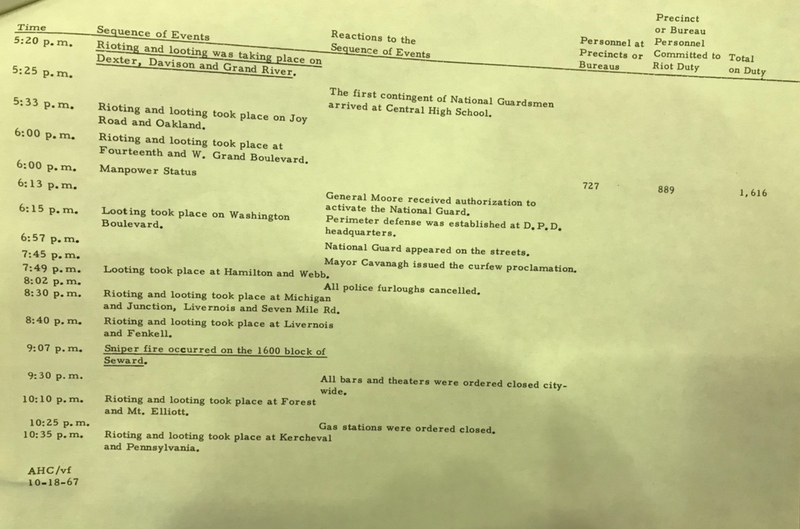

The remaining pages in this section and in the next Fatalities and Victims section provide more details and critical analysis of what happened and why, from multiple perspectives. The Investigations section presents the findings of official inquiries, and the final Visualizing Detroit '67 section emphasizes that the photographs and other visual and textual reports from media and government sources provide an incomplete, distorted, and often misleading or simply wrong version of events. Please keep this in mind when viewing all historical photographs in this 1967 section.

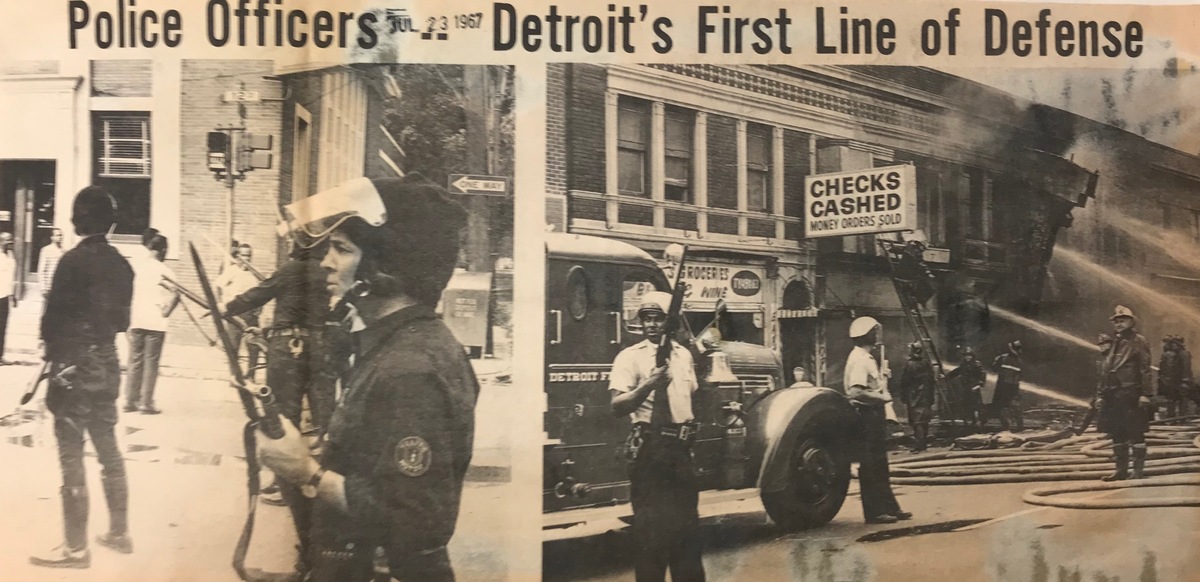

The above photograph collage is an example of how every image and historical document presents a particular perspective and hides or silences others. In these two images--a microcosm of the dominant account presented by the government and news media, and consumed by the general public--heavily armed DPD officers in riot gear patrol Black Detroit and protect firefighters who are putting out the damage caused by arsonists. The state is there to suppress the "riot" and keep the peace. The roles of the African American civilians in the photograph above left are ambiguous. Many perspectives and experiences of African Americans in Detroit between July 23-28 are absent from this narrative altogether.

12th Street and Clairmount: July 23, 1967 (Morning)

The Detroit Uprising began after the DPD's Tenth Precinct vice squad raided an unlicensed drinking establishment, known as a "blind pig," at 3:45 a.m. on Sunday morning, July 23, and began a mass arrest of 85 people, all African American (the next 12th Street Blind Pig page examines this event in detail). A crowd gathered outside the building, and around 5:00 a.m. someone threw a bottle at a police car and a few other people broke windows. The DPD soon deployed its militarized Tactical Mobile Unit, and the situation escalated from there.

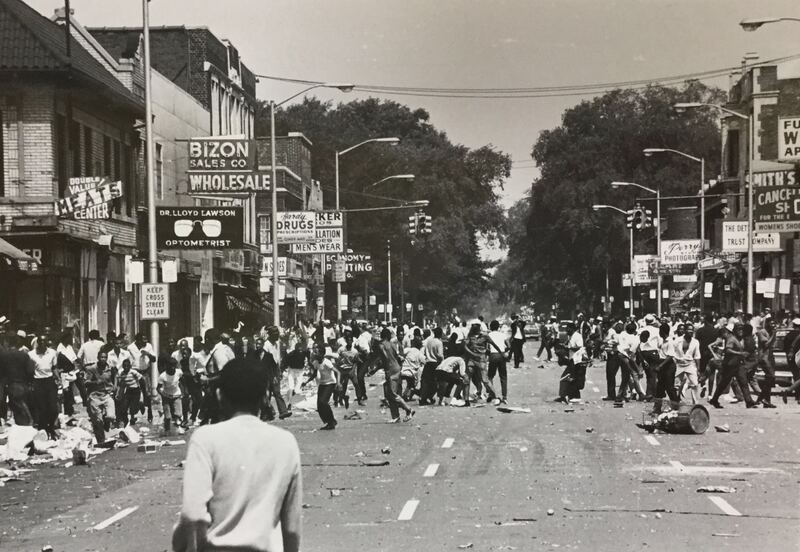

The famous Detroit News photograph of the street scene outside the blind pig (right) circulated widely in local, national, and international media. The blind pig is located at the far left end of this commercial block, above the Economy Printing Co. The photograph shows a mostly young crowd of African Americans, many teenagers or even preteens, on a street filled with debris. Many are running away from something, presumably the police, although exactly what is not clear.

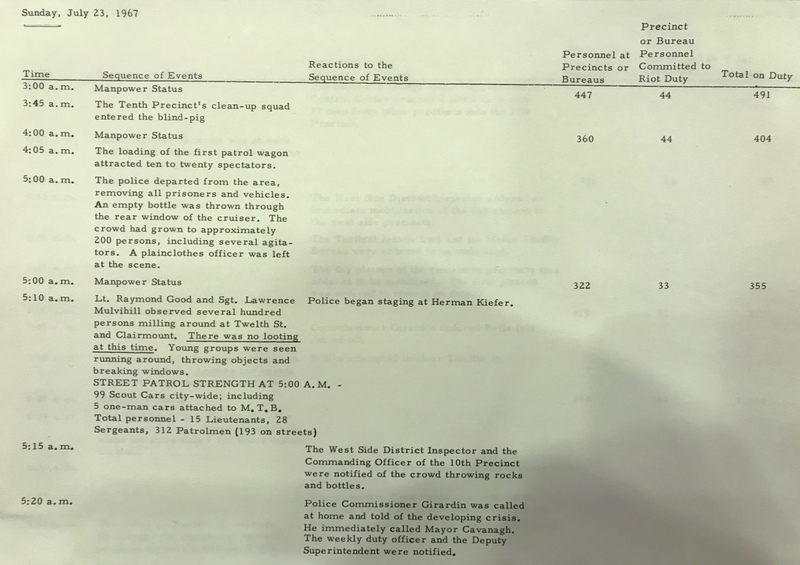

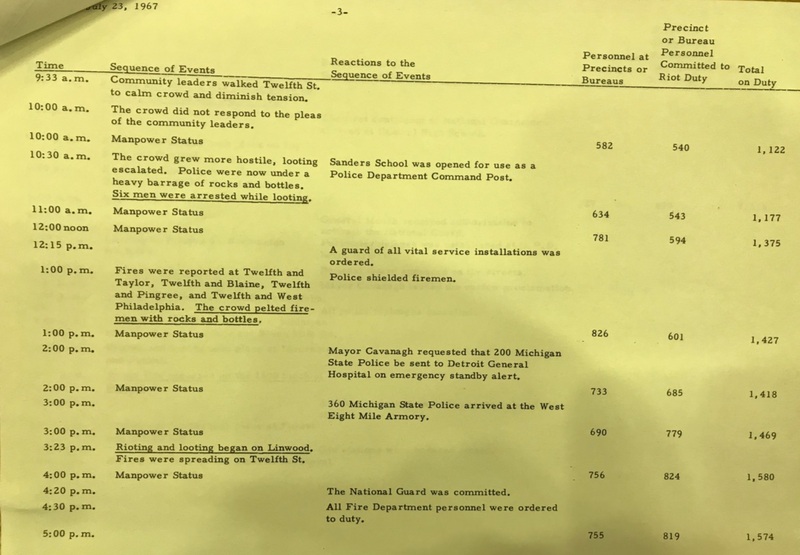

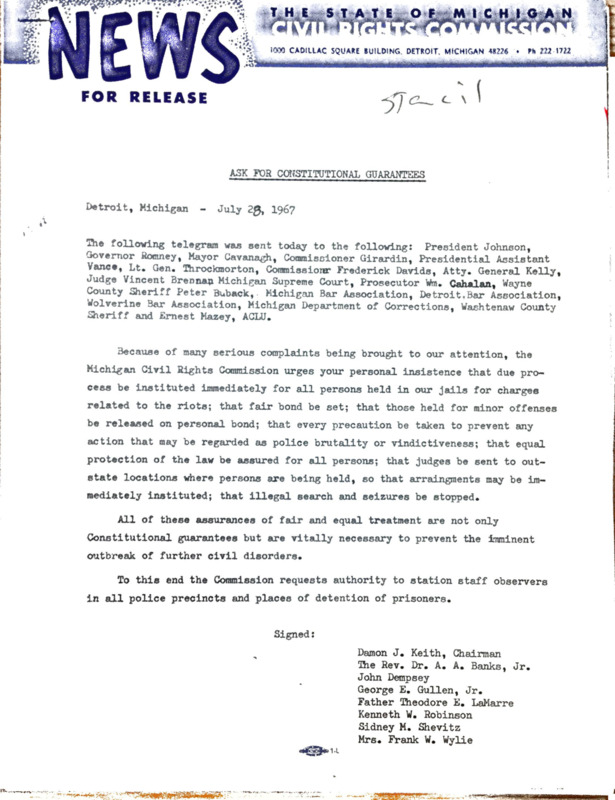

The DPD's official sequence of events, reproduced below, reads in part:

- "4:05 a.m. The loading of the first patrol wagon attracted ten to twenty spectators.

- 5:00 a.m. The police departed from the area, removing all prisoners and vehicles. An empty bottle was thrown through the rear window of a cruiser. The crowd had grown to approximately 200 persons, including several agitators. A plainclothes officer was left at the scene.

- 5:10 a.m. Several hundred persons milling around at Twelth [sic] St. and Clairmount. There was no looting at this time. Young groups were seen running around, throwing objects and breaking windows.

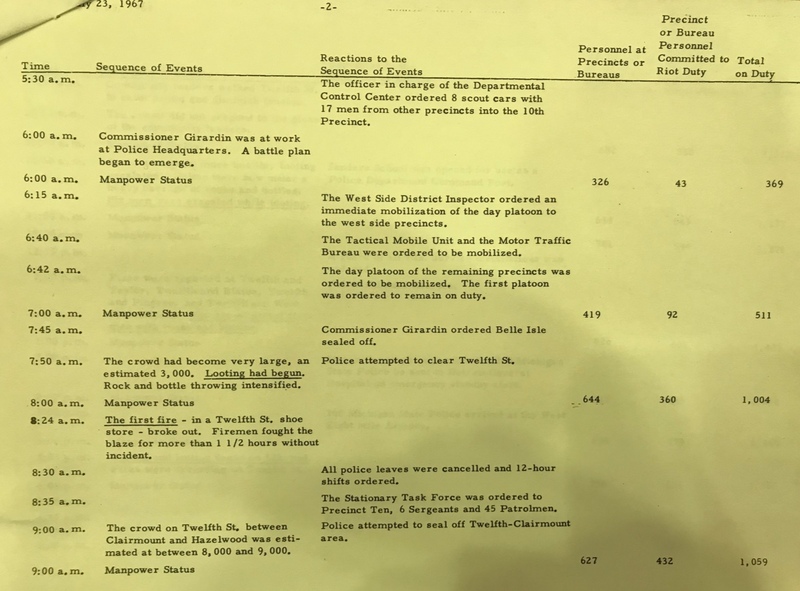

- 6:00 a.m. Commissioner Girardin was at work at Police Headquarters. A battle plan began to emerge.

- 7:50 a.m. The crowd had become very large, an estimated 3,000. Looting had begun. Rock and bottle throwing intensified.

- 8:24 a.m. The first fire . . . broke out. Firemen fought the blaze for more than 1 1/2 hours without incident.

- 9:00 a.m. The crowd on Twelfth St. between Clairmount and Hazelwood was estimated at between 8,000 and 9,000. Police attempted to seal off Twelfth-Clairmount area.

- 9:33 a.m. Community leaders walked Twelfth St. to calm crowd and diminish tension.

- 10:00 a.m. The crowd did not respond to the pleas of the community leaders.

- 10:30 a.m. The crowd grew more hostile, looting escalated. Police were now under a heavy barrage of rocks and bottles. Six men were arrested while looting.

- 1:00 p.m. Fires were reported at Twelfth and taylor, Twelfth and Blaine, Twelfth and Pingree, Twelfth and west Philadelphia. The crowd pelted firemen with rocks and bottles."

Read the Detroit Police Department's full timeline for the events of July 23 in the gallery below.

Calling in Reinforcements: July 23, 1967 (Afternoon)

At 2:00 p.m. on July 23, Mayor Jerome Cavanagh requested that 200 members of the Michigan State Police be mobilized on emergency alert downtown. At 3:00 p.m., 360 members of the Michigan State Police arrived at their armory on the city's outskirts, and by 9:10 p.m. 800 state troopers were in the city and deployed alongside DPD officers. [In its own chronology, the Michigan State Police stated that on the first morning, "no request for help or assistance was either made or needed by the Detroit Police Department," absolving itself of responsibility as events spiraled out of control].

At 3:23 p.m., the DPD reported "rioting and looting" on Linwood St. located several blocks away from the epicenter at 12th and Clairmount.

At 4:20 p.m., at Mayor Cavanagh's request, Michigan Governor George Romney mobilized the National Guard. (Cavanagh also consulted with traditional black community leaders, who also supported the presence of the National Guard). At 5:25 p.m., the first National Guard units arrived in the city, and they deployed on the streets at 6:57 p.m.

Between 5:20 p.m. and 8:40 p.m., the DPD reported the spread of "rioting and looting" to other locations in the city, mainly in the commercial districts of African American neighborhoods on the West Side of Detroit.

At 7:45 p.m., Mayor Cavanagh imposed an emergency curfew.

At 9:07 p.m., the DPD reported the first instance of (alleged) sniper fire.

Between 10:10 p.m. and 10:35 p.m., the DPD reported that "rioting and looting" had spread to several African American neighborhoods on the East Side of Detroit.

July 23 death count: 4 persons (2 died later of injuries suffered on July 23).

July 23 arrest count: 1,100 persons, mostly alleged "looters."

Note: On July 23, police commanders in the field appeared to have ordered restraint in the use of firearms, despite the general DPD policy permitting "all necessary force" to stop rioters and looters and to defend property. The DPD later received substantial criticism for not utilizing deadly force, or tear gas, to quell the riot in its early hours. That restraint would change, dramatically, on July 24, when the DPD gave its officers permission to shoot to stop looters.

The National Guard deployed with orders to protect property by shooting looters "if necessary" and also began utilizing deadly force on July 24.

Monday, July 24: Authorization to Shoot Looters

At midnight, Governor Romney declared a state of emergency in Detroit as well as in the mostly African American nearby munipalities of Highland Park, Hamtramck, River Rouge, and Ecorse. Romney also publicly stated that "violence and law breaking will not be condoned," understood as an endorsement of the National Guard's orders to shoot looters "if necessary."

At 3:00 a.m., Governor Romney made this threat explicit by stating that "fleeing felons are subject to being shot at." The National Guard was operating under more specific orders:

That morning, Governor Romney also asked the federal government to send 5,000 troops to assist local and state forces.

Between midnight and 5:00 a.m., according to government sources, rioting, looting, and arson escalated to the highest levels of the entire six-day saga. Law enforcement also reported sniper fire aimed at police officers and National Guardsmen, which escalated their response amid fears that they faced what DPD officials called "urban guerilla warfare." [There is significant evidence that in many if not most incidents, DPD officers and National Guardsmen were firing wildly and mistaking each other's gunfire for sniper attacks].

At 12:45 p.m., the DPD informed officers that they should "use discretion" in shooting looters. According to historian Sidney Fine, who gained access to many internal police documents, the DPD never gave an explicit order to shoot looters, unlike the National Guard. Instead, Mayor Cavanagh said that police officers should use their "professional judgment," and word circulated through the DPD that it "was all right to open fire."

President Lyndon Johnson dispatched Cyrus Vance, the deputy secretary of defense, to assess the situation after Governor Romney's request for the intervention of the U.S. military. By later in the afternoon of July 24, the first Army units arrived at an air force base located twenty miles from Detroit, and soon they began staging inside the city limits, awaiting presidential authorization to deploy.

A group of African American civil leaders and ministers also issued a call for a "strong police crackdown" to restore order and expressed support for the intervention of the U.S. military.

During the afternoon and evening, the DPD continued to make mass arrests, and DPD officials and National Guardsmen also fired often at alleged "looters," or just at African American people on the streets. Historian Sidney Fine labeled this a "tandem riot," where police officers and National Guardsmen operated with indiscipline and began deploying indiscriminate violence against African Americans on the street, no matter what they were actually doing. Journalists reported that white police officers or National Guardsmen made the following overheard comments:

- "They are savages"

- "Those black son-of-a-bitches. I'm going to get me a couple of them before this is over."

- "I'm going to shoot anything that moves and that is black."

At 11:20 p.m., Lyndon Johnson officially deployed two divisions of the U.S. Army paratroopers and federalized the Michigan National Guard. He did so reluctantly, "with the greatest regret," and made clear that Governor Romney and Mayor Cavanagh had requested the deployment and were "unable to bring the situation under control." The president also gave a nationally televised address near midnight and declared:

July 24 death count: 19 persons

July 24 arrest count: 2,931

Tuesday, July 25

In the morning, the first U.S. Army paratroopers arrived in Detroit. This allowed the redeployment of Michigan State Police units to address outbreaks in other Michigan cities (see document in gallery below).

The Army units, unlike the DPD and the National Guard, were highly trained and disciplined and under orders to "use the minimum force necessary to restore law and order." Army troops were specifically ordered not to fire on unarmed looters. This order also applied to the federalized National Guard, but many Guardsmen did not comply. (Army troops killed one person during the mobilization, compared to at least 22 fatalities by the DPD and at least 10 by the National Guard).

By contrast, DPD officers reported receiving unofficial orders that "the rioting and looting had to be squelched 'at all costs." Amid continued reports of sniper fire, police officers and National Guardsmen continued to shoot at invisible threats, alleged looters, and just black people on the street or driving around in cars.

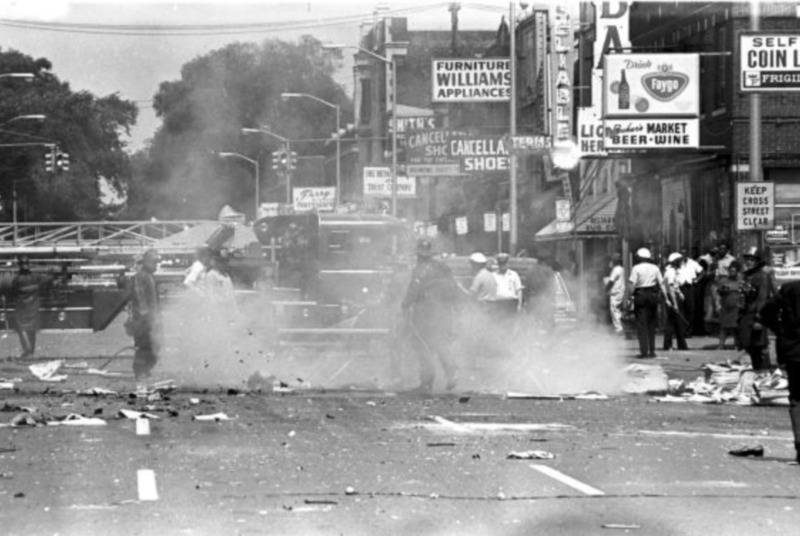

Jail facilities overflowed with prisoners who had been arrested, often indiscriminately, as a pacification strategy. The prosecutor declined to file prompt charges or set very high bonds, part of a deliberate effort to keep African Americans incarcerated until the situation stabilized. The Michigan Civil Rights Commission labeled this a violation of civil liberties and constitutional guarantees (right).

The governor and mayor joined Cyrus Vance, the Johnson administration's representative, to urge businesses in the city to reopen.

July 25 death count: 10 persons, including a four-year-old girl

July 25 arrest count: 732

Wednesday, July 26

Hubert Locke, a civil rights advocate who worked for the police department, reported that by Wednesday morning, many DPD officers had stopped wearing their badges and had taped over the numbers on their squad cars.

In the early morning hours, a group of white police officers murdered three unarmed African American teenagers in the Algiers Motel.

Reported incidents of looting and arson declined significantly.

July 26 death count: 10 persons

July 26 arrest count: 425

Thursday, July 27

On Thursday morning, Governor Romney lifted the full-time citywide curfew, but kept the nighttime curfew in place.

Mayor Cavanagh announced the appointment of the New Detroit Committee to oversee Detroit's recovery and improve race relations.

July 27 death count: 1 person

July 27 arrest count: 300

Friday, July 28

On Friday, July 28, the Johnson administration began withdrawing federal troops from Detroit, and the Michigan National Guard also stood down.

The city and county announced the release of people arrested for looting and curfew violations, if they were able to post bond, citing the extreme overcrowding of detention facilities.

On Friday evening, Governor Romney accounced that Detroit was secure.

July 28 death count: 1 person

Saturday, July 29

July 29 death count: 1 person (the only fatality by an Army paratrooper)

July 30

The last Army troops left the city.

July 31

The Detroit Police Department retured to normal shifts.

August 1

All curfew restrictions lifted.

August 6

The last Michigan National Guard units left the city.

Governor Romney lifted the state of emergency and declared a day of mourning.

The gallery below includes the short and full chronologies of the "Detroit Disorder" compiled by the Kerner Commission's investigative staff, a chronology of the first morning by the Michigan State Police, and a Michigan Civil Rights Commission memo on racial disorders in other Michigan cities.

References

George Romney Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

Jerome P. Cavanagh Papers, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Civil Rights during the Johnson Administration, 1963-1969, Part V: Records of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders (Kerner Commission), Lyndon Baines Johnson Presidential Library, Austin Texas (ProQuest History Vault)

Sidney Fine, Violence in the Model City: The Cavanagh Administration, Race Relations, and the Detroit Riot of 1967 (Lansing: Michigan University Press, 2007)

Hubert G. Locke, The Detroit Riot of 1967 (1969, reissued 2017)

Detroit Historical Society