II. Demanding Reform (1978-81)

Note: section 2 is still in development and should not be cited or quoted or reproduced without contacting mlassite@umich.edu first. The police homicide data in this section is incomplete--the pages on affirmative action and other themes in this section are generally complete.

Mayor Young's Second Term and Affirmative Action

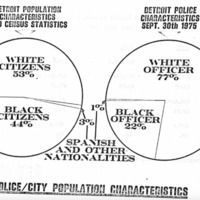

The late 70s brought many reforms for the Detroit Police Department. In 1978, Coleman Young was re-elected for a second term as mayor of Detroit. During his first term, Young had made important progress changing the nature of policing in Detroit. Among his accomplishments prior to 1978 were the opening of several police mini stations and the abolition of STRESS, the undercover cop unit responsible for a large number of civilian deaths. Coleman Young had pledged to usher in a new era of policing in Detroit, one that emphasized responsiveness to citizen complaints, accountability, and positive relationships between the community and the police. In the aftermath of the deadly STRESS era, Young believed that racial representation in the police force would improve police relations with the community. He instituted affirmative action initiatives in police hiring and promotions that aimed to substantially increase the representation of African Americans and women in the police department. By as early as 1974, the number of black officers hired by the department surpassed the number of white officers for the first time in the city’s history. Affirmative action policies also helped raise the number of black sergeants on the force from 4% to 9%. These reforms did not come without resistance, however. The city's two mostly white police unions filed legal complaints against the policy, and a lengthy legal battle over affirmative action ensued. Young’s policies resulted in fractures in race relations within the police department, bringing to question the effectiveness of affirmative action on not only the culture within the DPD, but also the relationship between the DPD and the community.

Although these were important gains, they were not enough to match the changing demographics of the city which, by 1980, was almost 65 percent black. Entering his second term, Young recommitted himself to creating meaningful changes within the police department, including fighting back against police brutality.

The War on Drugs and Narcotics Corruption

The War on Drugs ushered in an era of hysteria over heroin traffic in the United States. In 1971, Richard Nixon called for an attack on narcotics activity across international borders. Of course, these problems were not just foreign issues. Many Americans were concerned with the U.S. federal government’s stake in heroin traffic, both internationally and domestically. Residents of drug-plagued cities were familiar with their local governments’-- namely the police-- role in colluding with drug dealers. Detroit experienced its fair share of narcotics corruption. Archival documents such as citizen complaints and documented instances of police involvement in narcotics trade point to a pattern of misconduct that suggests that some police in Detroit were personally benefitting from the mass criminalization of drugs.

Fighting For Reform

Coleman Young was by no means the only strong political actor in Detroit during the late 1970s. Feminist organizers, Black Power organizations, radical leftists, middle class African Americans, white conservatives, and the majority white police unions were all extremely active in the debates over policing reform at the time. While these groups had differing perspectives and priorities that they advocated for through public discourse to direct action, they all would come to play important roles in shaping the development of policing in Detroit entering the new decade.

Under-Policing and Over-Policing

The Social Conflict Task Force (SCTF) was one of the many prominent groups advocating police reform in Detroit in the 1970’s. Created by city Councilwoman Maryann Mahaffey in 1974 to help improve the police response to domestic violence cases, the SCTF conducted research that provided incredible insight into the disparity between how violence was commonly viewed in Detroit during the time and the reality of violence in the city. By the 1970’s, Detroit had gained a reputation as the murder capital of the United States. Policing in Detroit often focused on violence related to theft, gangs, and narcotics markets. Assaults and homicides were therefore often framed as random acts of street violence that could befall anyone in the city at any time. The focus on random street violence, however, obscured the larger picture of the interpersonal violence driving Detroit’s high murder rate. A 1974 report from the Social Conflict Task Force to the city council revealed that over half of the homicides in Detroit were between people who knew each other. A substantial portion of homicides stemmed from domestic violence disputes in which police were the first responders. Police at the time, however, were thoroughly unprepared to deal with domestic violence situations, which were already low priority. Police often did not arrive in time to prevent domestic violence, and when they did, they sometimes escalated the conflict further. Attitudes towards women influenced how seriously police took these cases and much of the work to ameliorate the situation was done by community action groups and the dedication of public servants.

The Social Conflict Task Force report reveals a larger problem plaguing Detroit during the 1970’s and early 80’s: simultaneous under and over- policing. As police in Detroit made thousands of arrests a year for relatively minor crimes such as drug possession or larceny, many citizens and community organizations felt that they were ignoring the city’s real problems. In 1979, for example, the criminal justice system in Detroit prosecuted almost a hundred more people for vagrancy than they did for rape. Despite thousands of annual narcotics arrests during the period, citizens routinely wrote to their city council representatives or the Mayor’s office to draw attention to narcotics activities taking place openly in their neighborhoods. The priorities of the department seem to have been somewhat removed from the real issues facing the citizens of Detroit.

Silences and Politics of the Archive

Throughout the archives, we’ve noticed an absence of official documentation of complaints about the mishandling of domestic violence cases. Given what we know about the negligent nature of domestic violence policing during this period, this archival silence indicates that the police were not taking these reports seriously. Much of the archival evidence we did find of the underpolicing of domestic violence was discovered in the papers of Diana Warshay and Councilwoman Maryann Mahaffey, two prominent white women working on women’s rights during this period, rather than in Mayor Young’s or the City of Detroit’s legal department files. Identifying black women's perspectives on the policing of crimes against women was another challenge, as the archival materials we found amplified the voices of white feminist organizers. These disparities suggest that domestic violence issues were not dealt with through official legal channels, and raise questions about the kinds of women whose complaints made it to the archives. We must also ask for whom were domestic violence complaints pursued even after these cases were taken more seriously by the police.

We had to navigate the politics of the archives when evaluating newspaper sources, as well. This issue arose upon analyzing the representation of the political environment around the War on Drugs in the Michigan Chronicle, a black newspaper in Detroit, compared to that of predominantly white newspapers like the Detroit News and the Detroit Free Press. The white papers were easily available online and that allowed us to quickly identify articles that were relevant to this project but The Michigan Chronicle was only available on microfilm and the Hatcher Graduate Library. This severely restricted our ability to research using The Chronicle since we could only access it when the library was open and we were required to search through every page in order to find relevant information. This did not mean that The Michigan Chronicle was an entirely silent archive but it meant that our access was very restricted and the articles written within were more likely to go unseen in our research.

The discontinuity between what is present in the archives and what we know about police behavior throughout our time period speaks to the political nature of archival research. Archives are not necessarily neutral or objective repositories of history. Silences in the archival record often say more than what is materially present.

Sources:

Coleman A. Young Mayoral Papers, Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library.

Maryann Mahaffey Papers, Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library.

Virtual Motor City, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.