How Successful Was Affirmative Action?

In 1967, less than a decade before Mayor Coleman Young took office, African-Americans made up just under 5% of the Detroit Police Department (DPD), despite being around 40% of the city’s total population. Responding to that clear disparity, as well as pressure for reforms from civil rights groups such as the Detroit Urban League, Mayor Young started an affirmative action program soon after being elected. The program sought to make the police better represent the racial demographics of the city as a whole, as well as to increase the representation of women on the force. Mayor Young’s program of affirmative action included hiring and promoting more black and female officers, as well as decreasing the role of seniority in the determination of layoffs, since senior officers were more likely to be white due to the long history of discrimination against black police in Detroit.

Despite large scale resistance against affirmative action from the Detroit Police Officers Association (DPOA), a majority white police union, by the end of the 1970s the Detroit Police Department had made major strides in the levels of African-American representation on the force. In 1981 the DPD was almost 30% black and 9% female, a huge improvement from the extremely low representation of women and minorities that existed during the first half of the century. By 1993, the DPD finally reached a 50-50 split between white and black officers, including those in leadership positions, making the force the most representative of the city’s racial demographics since the early 1900s. Overall, on the basis of racial representation alone, it is clear that Mayor Young’s affirmative action policies were a relative success. That being said, even by 1993, women were still relegated to a very small portion of the department’s ranks.

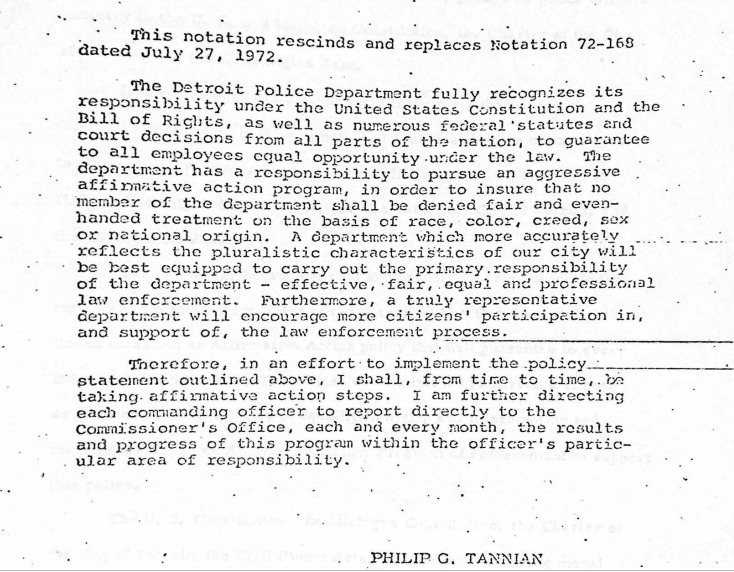

Racial representation for representation’s sake was not, however, the only goal of affirmative action in the Detroit Police Department. Ideally, according to Police Commissioner Philip G. Tannian, the policy was meant to increase the effectiveness of policing in Detroit, reduce the role of racial biases in policing, and improve police-community relations. Whereas the success of affirmative action in changing the racial makeup of the department can be easily and objectively analyzed, it is much harder to interpret to what extent that change helped improve policing in Detroit. The goals proposed by Tannian, however, do provide some framework for evaluating the impacts that affirmative action had in Detroit.

Promoting Effective Policing

Whether or not affirmative action policies helped the police operate more efficiently and lead to a reduction of crime is, and was, a matter of debate. At a press conference announcing a convention of the National Organization of Black Law Enforcement Executives in Detroit in 1979, Mayor Coleman Young boasted that his affirmative action program, especially its increase in the number of black sergeants and lieutenants, had led to a 30 percent reduction in crime in Detroit. While it is certainly true that there was a large reduction in crime between 1976 and 1979, it is less obvious that that reduction was, as Mayor Young claimed, directly related to his affirmative action policies. Budget problems in Detroit during 1975 and 76 had led to massive layoffs in the DPD for those two fiscal years. After the budget crisis was somewhat mitigated, many police were rehired which likely also contributed to the decrease in crime over that time period. It is possible that affirmative action also played a role, but it was by no means the only major change that the department underwent as crime started to decrease.

It is quite likely that the presence of more black officers played some role in improving the Detroit Police Department’s ability to effectively work within predominantly black communities and catch and process criminals. The increase in female officers on the force, for example, made it easier for the department to handle female suspects, especially in light of complaints of male officers conducting strip searches. Additionally, African American officers were presumed to be better equipped to operate within the cultural milieu of black Detroit and thus better able to conduct investigations in those areas. The extent to which that actually was the case is somewhat debatable, especially without knowing the socioeconomic makeup of the many black officers that joined the police force during the 1970’s and 80’s. It is unclear whether or not the majority of black officers in the DPD actually came from the impoverished neighborhoods that they often ended up policing. Regardless of black officers ability to better integrate themselves into the communities in which they worked, it was certainly advantageous for the DPD to have a more diverse base of officers to use in undercover operations such as drug buys.

In some ways, however, the introduction of affirmative action may have actually hurt the department's efficiency. For one thing, affirmative action increased racial tensions between white and black officers. As exemplified by the assault of black Officer William Green by several off duty white officers, these racial tensions could boil over and cause serious problems for the department. Throughout the implamentation of affirmative action the resistance of white officers through formal and informal means erroded the cohesion of the DPD, drained DPD resoureces throgh costly legal struggles, and disrupted the day to day operations of the department.

Additionally, affirmative action in hiring led to a sharp influx of inexperienced, and sometimes undertrained rookie officers. In the summer of 1977, for example, the DPD rushed a class of new police officers through a “crash course” program which was conducted in just 8 months instead of the standard 12 month porgram that most officers went through at the time. About a year later the Detroit News reported that at least 9 of those recruits had already been involved in gun related accidents. Those accidents included both shootings of civilians as well as several officers accidentally injuring themselves while handling weapons.

Affirmative action did have huge effects on the Detroit Police Department literally altering the face of policing in the city. The change, however, was not merely aesthetic. The scale of affirmative action within the DPD ensured that it changed the way that policing was conducted by fundamentally altering the dynamics of the force. Although many of the changes brought by affirmative action were advantageous and helped improve policing, the harsh reactions against it and the increase of inexperienced officers that it brought with it complicated the policy's impact. That complicated mix of positive and negative impacts as well as the variety of other changes that were affecting policing in Detroit at the time make it impossible to determine with absolute certainty the extent to which affirmative action may have improved the efficiency and effectiveness of crime control in Detroit.

Reducing Racial Bias and Improving Police-Community Relations

The historical record is also somewhat unclear when it comes to the impact that affirmative action had in reducing the racist culture that was ubiquitous within the Detroit Police Department and improving the often fraught relations between Detroit cops and the citizens they were supposed to protect. It is relatively clear that, at the very least, affirmative action in promotions increased the number of black superior officers and provided the black rank and file with some degree of recourse when they experienced racist treatment from their white peers. Interviews with black police officers who were on the force before and after the start of the affirmative action program confirm that the policy improved conditions for African American officers. Both former DPD Officer David Bruce as well as former Chief of Police Isaiah McKinnon described in interviews how outright racism between cops declined as more black officers were put into superior positions.

The higher number of black officers and the increase in black leadership also seem to have increased public trust in the police department, at least during the beginning of the affirmative action program.

The short video above shows former Chief of Police Isaiah "Ike" McKinnon being asked about a surge in citizen complaints after the election of Mayor Young and the start of the affirmative action program. McKinnon responds by explaining how the election of a African American mayor coupled with an increase in black representation throughout the police hierarchy helped generate increased trust in the police and law enforcement institutions. According to McKinnon, the increase in complaints demonstrates not that officers were committing more misconduct, but that residents felt that they had representation within the police force and that for the first time their complaints would be heard. Although renewed faith in law enforcement may have been an early result in the rise of representation within the DPD, the number of archived complaints starts to drop off again during the mid to late 1970’s. There are multiple ways to interpret that decrease in complaints. It is possible that affirmative action and African American leadership radically changed the culture of the department and greatly reduced the amount of officer misconduct. A more pessimistic explanation is that Mayor Young’s administration failed to sufficiently reform the DPD and residents once again started to believe that their issues would remain unresolved. It is quite possible that decreased excitement about Young’s reforms worked in tandem with incremental improvements in policing to generate a lower number of complaints. Nevertheless, the surge of citizens writing complaints against problematic police conduct after Young’s election demonstrates that African American representation could and did increase trust in the DPD, even if it was only temporary.

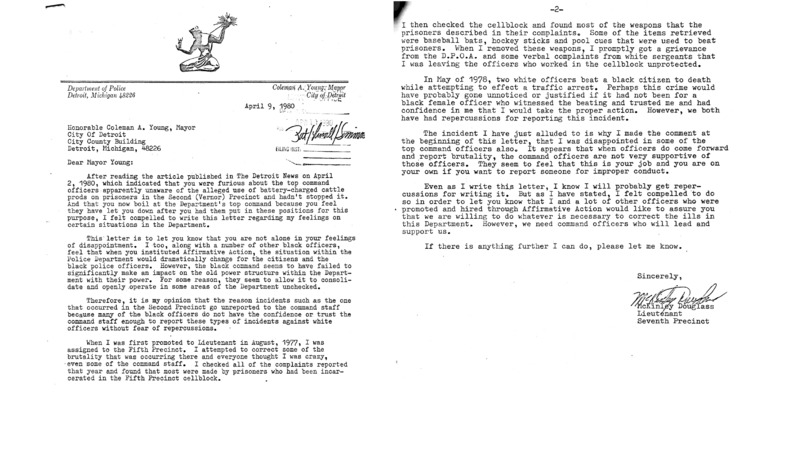

Sentiment from Black officers within the DPD suggests that affirmative action may not have led to the culture change Mayor Young hoped for. In his letter to Mayor Young in 1980, Lieutenant McKinley Douglass of the Seventh Precinct expressed that while he, along with other Black officers, thought that affirmative action would dramatically improve the situation of Black citizens and police officers, the increased presence of Black officers in the DPD was not enough to tackle decades of reinforcement of racist power structures. The sheer number of Black officers joining the force did not mean that those in authority, mostly white officers, regarded Black officers’ contributions with respect. Lieutenant Douglass explains that when he joined the force in 1977, he attempted to expose and correct the brutality committed against incarcerated persons in the Fifth Precinct cellblock. When he followed up on prisoners' complaints, corroborating many of them, he suffered verbal harassment from white sergeants accusing him of leaving the offending officers “unprotected.”

The racial tensions provoked by affirmative action produced a situation where many Black officers could expect that reporting misconduct by white officers would make themselves subject to retaliation. Douglass describes how he and a Black female officer faced repercussions after reporting an incident of two white officers beating to death a Black citizen during a traffic stop. In this way, the racially polarized environment within the DPD also allowed for misconduct and corruption— especially as committed by white officers— to go unchecked.

Lieutenant Douglass’s letter speaks to the complex racial dynamics produced within the DPD by Young’s affirmative action reforms. Douglass concludes his letter by acknowledging that he will likely face repercussions for writing the letter, but feels compelled to assure Mayor Young that “other officers who were promoted and hired through Affirmative Action… are willing to do whatever is necessary to correct the ills in this Department.” By entrusting affirmative action with the task of bettering police-community relations, it seems that some Black officers felt disproportionately responsible for correcting improper conduct within the DPD, an undertaking that would have been nearly impossible amidst the racist power imbalances within the department.

Although a greater number of African American superior officers helped give rank and file with a way to fight intradepartmental racism, affirmative action did not entirely eliminate the racist culture within the DPD. Additionally, while affirmative action, especially in its first few years, contributed to an improved relationship between police and the Detroit community, it did not fully mend the attitudes of distrust and resentment that many citizens held in regards to the police department. Later events, such as the killing of Malice Green and the conviction of former Police Chief William Hart for embezzlement in 1992, would only serve to further erode trust in the police at the same time as the city was finally achieving full representation in its police department. In short, although affirmative action may have provided some boost to police community relations and helped to decrease the amount of open racism within the DPD, the police department would continue to have to fight an uphill battle in order to fully convince the citizens of Detroit, especially the African American citizens, that they were all on the same team.

Sources:

Detroit Police Department, Anual Report, Serial. (DPD, 1970-1981).

Coleman A. Young Papers, Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library.

The Detroit News, NewsBank.

Interview of Isaiah "Ike" McKinnon by Matt Lassiter and HistoryLab Team, December 3, 2019, Ann Arbor, MI.