Drug Corruption

The War on Drugs ushered in an era of hysteria over heroin traffic in the United States. In 1971, Richard Nixon called for an attack on narcotics activity across international borders. It was well known that high ranking government officials in Burma, south Vietnam, Laos, and Thailand were directly involved in heroin trafficking. Of course, these problems were not unique to Southeast Asia. Many Americans were concerned with the U.S. federal government’s stake in heroin traffic, both internationally and domestically. Residents of drug-plagued cities were familiar with their local governments’-- namely the police-- role in colluding with drug dealers.

10th Precinct Narcotics Conspiracy

In 1973, the Wayne County Citizen’s Grand Jury requested indictments against 22 Detroit police officers for involvement in heroin trafficking. Whites Against Repression (WAR), a group described as “progressive whites” organizing against heroin corruption and STRESS in the city, petitioned to initiate a probe into the matter by the Citizen’s Grand Jury. The following year, ten Detroit police officers in the 10th precinct were charged with drug trafficking. Witnesses testified that the defendants were involved in a “lucrative dope ring” that operated on Pingree Street on the city’s west side. Police officers allegedly took bribes from drug dealers in exchange for protection against raids and arrests. Two of the original defendants and one witness were suspiciously murdered after the indictments.

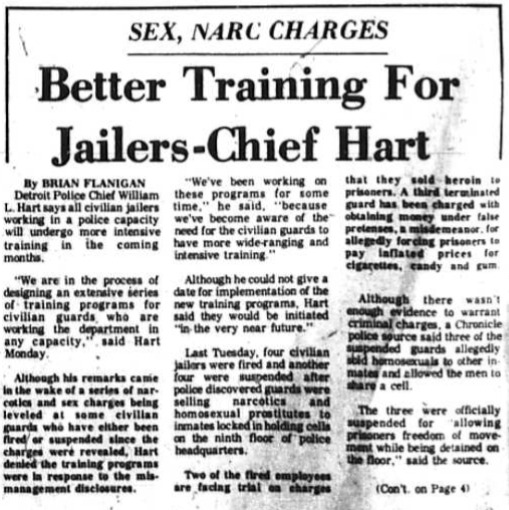

Situations like these were not simply isolated instances of misconduct. In 1978, 8 guards were disciplined for “selling narcotics and prostitutes” to inmates in holding cells on the 9th floor of police headquarters. Investigation into police conduct began when prisoners started complaining that their money and valuables were stolen while being detained.

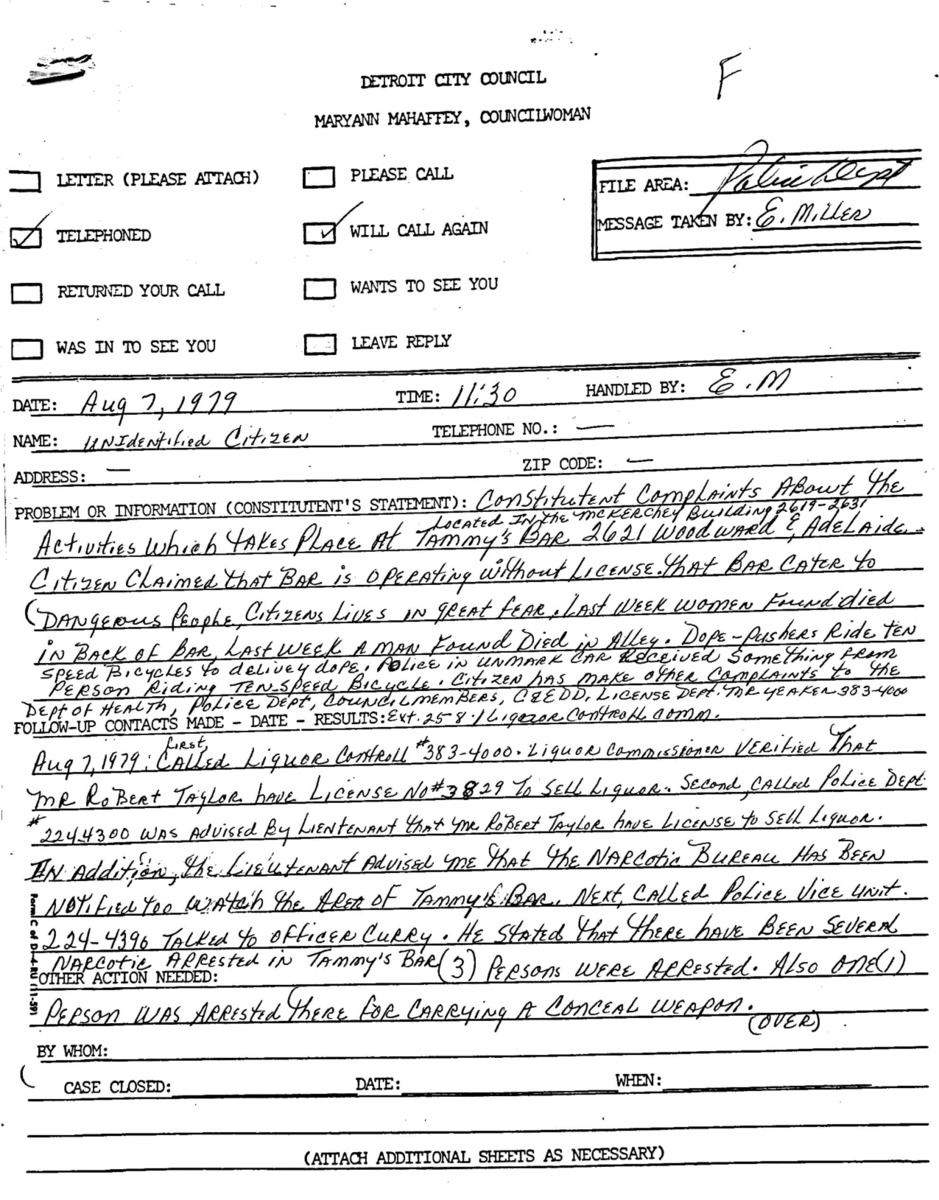

The blatant underpolicing of narcotics in certain neighborhoods by the DPD suggests, among other things, an underlying pattern of corruption in narcotics enforecement. Frequently, evidence of drug corruption came from citizen complaints sent to the Department of Health, city council members, and the police. In 1979, citizens wrote to Councilwoman Mahaffey about possible police involvement in drug activity at a local bar. They believed that the bar had been operating without a liquor license, and claimed to witness a deal between a drug runner on a bike and a police officer in an unmarked car. Citizen complaints claimed that the bar catered to “dangerous people,” and feared that recent deaths in the alley behind the bar were related to narcotics activity. In the investigation following the complaints, the police claimed that the deaths were accidental. The report does explicitly list three narcotics arrests made at the bar, possibly in attempt to dispel any suspicion that the police were protecting illegal activity at the bar. The report did not address allegations of police participation in narcotics trafficking.

While it is very difficult to detrmine the full extent of drug corruption within the DPD during the late 1970s and early 1980s, we do know that it existed. Based on the large scale of well documented corruption and narcotics conspiracies that took place directly before and after the period (the 10th Precinct conspiracy and the conviction of Chief of Police William Hart for embezzeling confiscated drug money, respectively) , it is clear that some DPD officers, even those at the top of the departtment, were willing to fully enjoy the benifits of drug money even if it meant their own participation in illegal actvities and narcotics markets.

One-Man Grand Jury

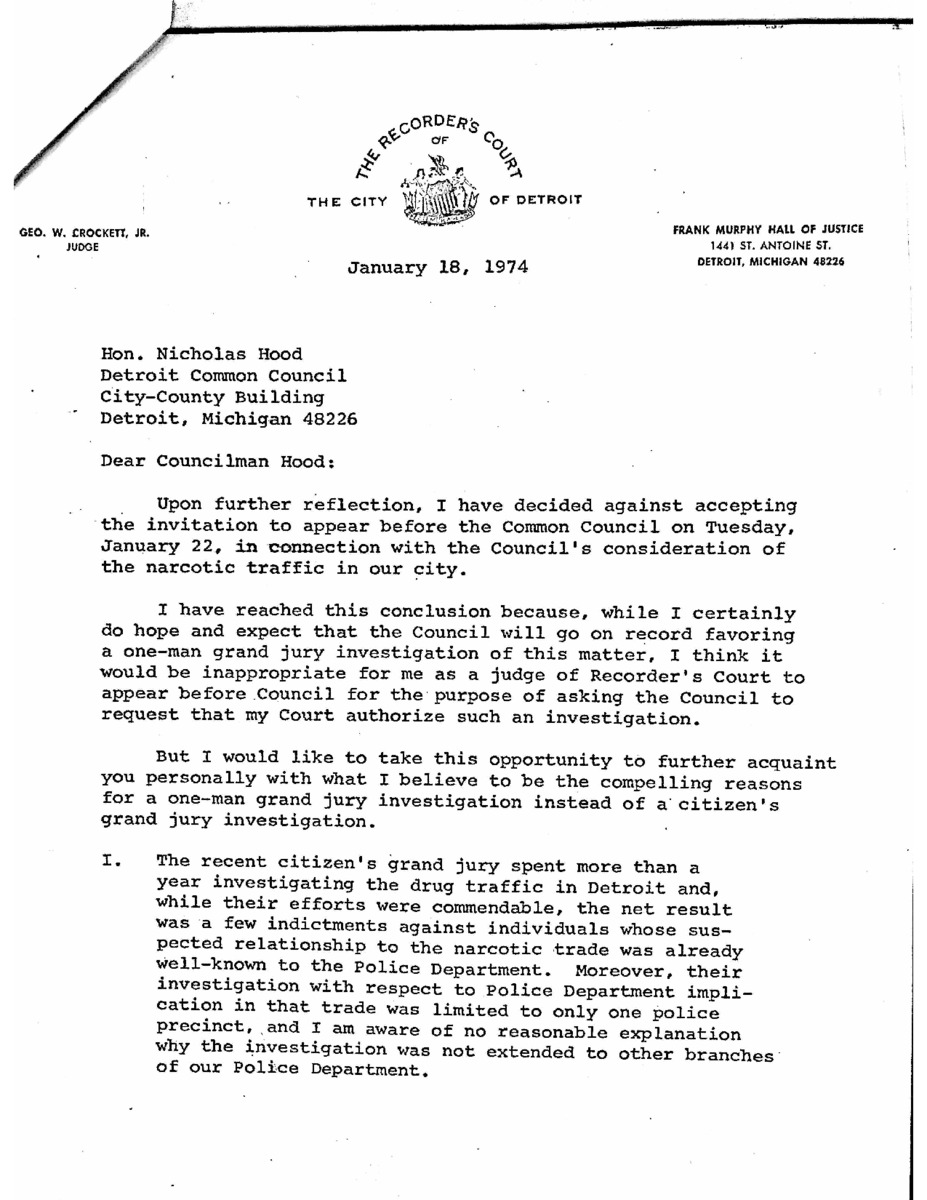

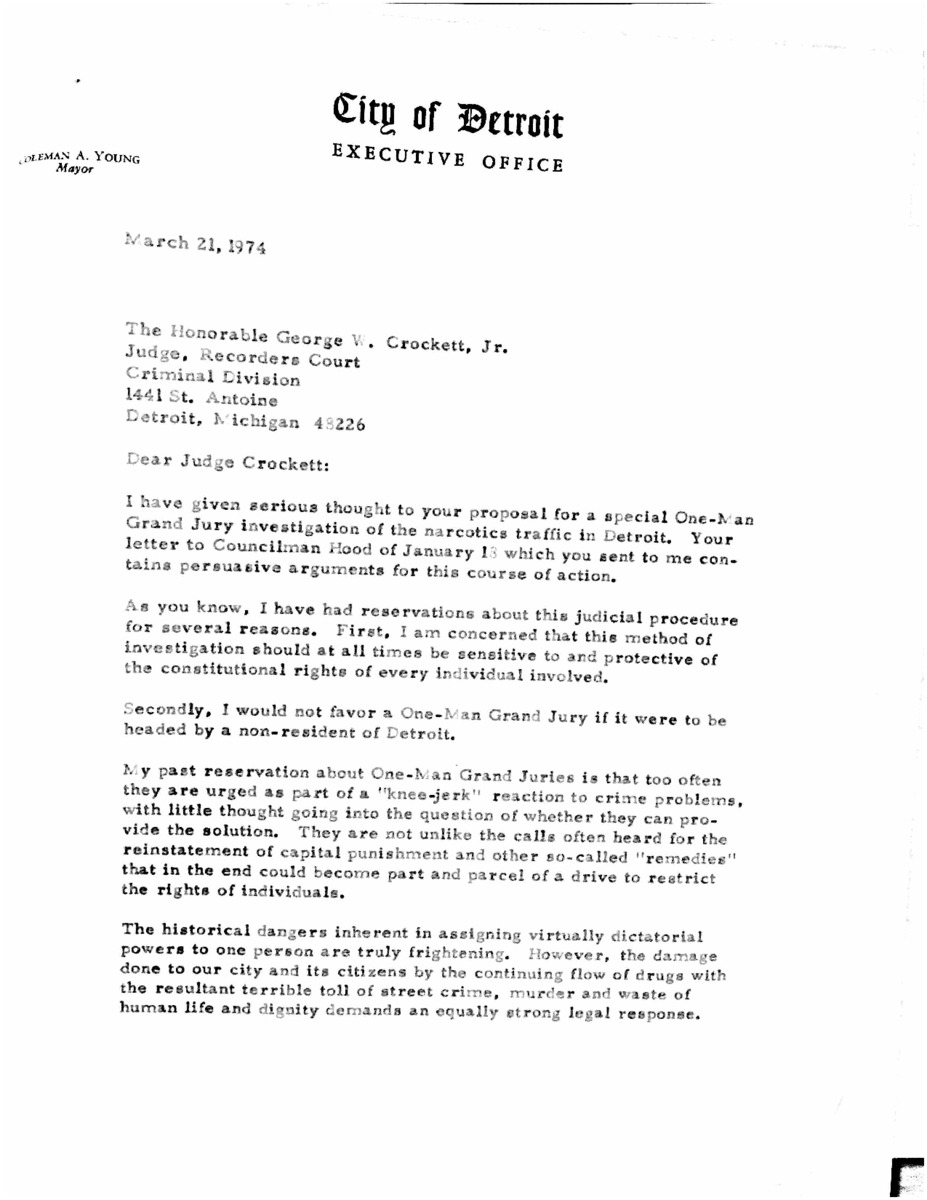

Community concerns of a rigged judicial system prompted calls for a “people’s court”-- a judicial institution that empowers and honors the needs of citizens-- to try the major players of heroin trafficking in Detroit. Public officials, however, had something else in mind. Judge George Crockett, an African American judge who presided over the Wayne County Recorder’s Court from 1969 to 1978, advocated for a one-man grand jury as the most effective way to investigate narcotics corruption and procure justice. A one-man grand jury involved a single judge investigating a case instead of a traditional grand jury composed of citizens. He cites the inefficiency and narrow scope of the citizen’s grand jury investigation as support for his argument, as well as its position under the Prosecutor’s Office and the Police Department. Skeptics of the one-man grand jury argued that the process gave too much power (“dictatorial power”) to a single person, thus raising questions about the constitutional rights of individuals involved. Still, proponents of the one-man grand jury argued that the method had the necessary capacity to efficiently prosecute drug traffickers. Mayor Coleman Young, in response to Judge Crockett’s proposal arguing in support of the one-man grand jury instead of the citizen’s grand jury, conceded “I now agree that the One-Man Grand Jury may be the most potent, viable and hopeful method of rooting out the cancerous evil of drugs from our city.”

SOURCES:

"Better Training for Jailers- Chief Hart," (May 4, 1978), Michigan Chronicle, Hatcher Graduate Library

Citizen Complaint, (August 7, 1979), Box 39, Folder 10, Maryann Mahaffey Papers, Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library

Letter to Councilman Hood from Crockett, (January 18, 1974), Box 11, Folder 17, Coleman A. Young Papers, Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library

Letter to Judge Crockett from Young, (January 18, 1974), Box 11, Folder 17, Coleman A. Young Papers, Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library

Weinbaum, Mary, “The Heroin Empire,” (July-August 1973), Groundwork: From the Ground Up