Media Bias and White Support for Crash

The crash program implemented by Mayor Miriani and Police Commissioner Hart received strong support from the white-owned media and from the majority of white residents of Detroit. Civil rights organizations and some white liberals opposed the crackdown and mass arrests, but their voices were drowned out by the intense focus on the two white female victims and the widespread fears that black crime had spiraled out of control in the city.

Newspapers and the Race-Based Crime Crackdown

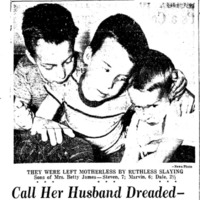

The two mainstream newspapers, the Detroit Free Press and Detroit News, hyped the alleged crime wave, cheered on the police crackdown, and provided saturation coverage of white victims of violent crime in ways never done for black victims. The Detroit News even announced separate $5,000 awards for the capture of the killers of Marilyn Lou Donohhue and Betty James. The Free Press ran multiple stories about the family of Betty James and warned the public of the "recent attacks by Negro men on women in heavily travelled areas of Detroit."

At the height of crash, the Detroit News reported that the city had experienced 157 murders during 1960, the most violent year on record since 1931. The point was to justify the crash program, but the statistics also raise the question of why these two victims, whose suspects were "Negro men," received such disproportionate attention from the city government, police department, news media, and general public.

Numerous articles in the Free Press and Detroit News recounted the pervasive fear of violent crime across Detroit, focused primarily on the fear as experienced by white people. Citizens were terrified to walk alone at night, husbands did not want their wives to walk to work, people were afraid even to go to the grocery store. Media coverage amplified these fears, especially after the second Betty James slaying. The white newspapers focused extensively on her vulnerability as a white working-class mother who had a job in the dangerous business district, and portrayed her despondent husband and abandoned children as a tragedy that could happen to any reader. The DPD announced that other nurses who worked at the hospital where Betty James had been employed could call a police officer for an escort home.

The Detroit News and Detroit Free Press also presented the crash program as a great success, repeating the line from the mayor and DPD. On Dec. 30, Commissioner Hart announced he was "pleased with the program" and that "the program is getting the desired results. It apparently is driving the undesirables under cover or out of town. That is what we had hoped with happen." Two weeks later, the Free Press reported that purse snatchings dropped 68 percent, robberies were down 27%, and the city experiences 26 fewer burglaries. The newspapers also reported that the police had confiscated 1,296 dangerous weapons and other items in the mass street-sweep operation that searched 150,000 African American men and arrested 1,500 without cause. The coverage did not focus on the constitutional rights of innocent citizens, except when civil rights groups forced the mayor and DPD to address this angle, and implied that the city was safer even though the police still had not solved the murder of either Marilyn Lou Donohue or Betty James.

Mobilizing the Public

Mayor Miriani and Commissioner Hart also issued a "call to action" for community involvement in the crash crackdown. Hart asked "for citizen’s aid" in helping police to identify criminals. Residents of Detroit responded, and by January 1 the police had received more than 400 tips in the murder investigations. The Detroit News, which was offering cash rewards, received hundreds more.

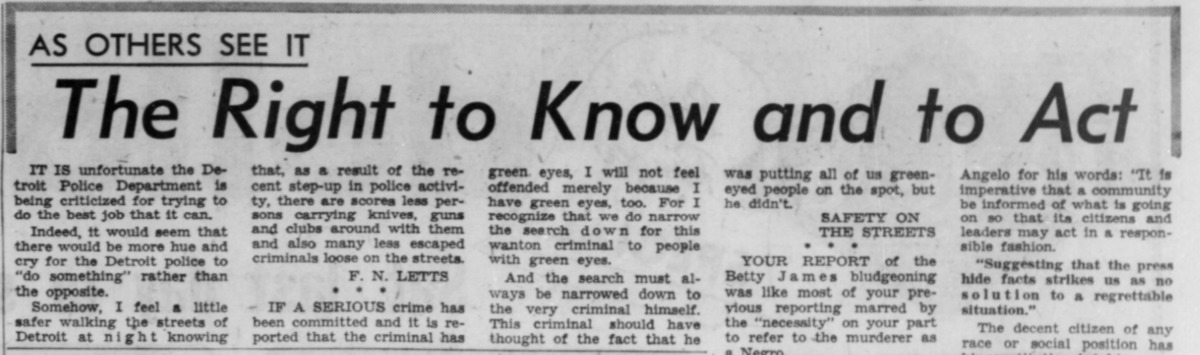

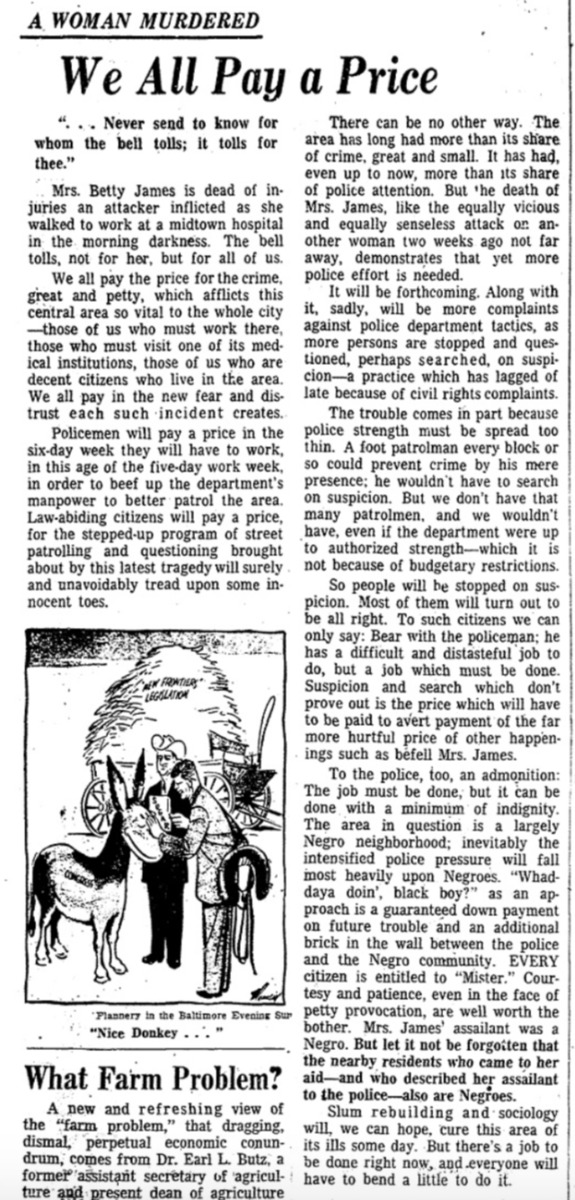

On Dec. 29, the Detroit News published an editorial titled "We All Pay a Price" (see below gallery) The essay lamented the death of Betty James and what it meant for the "decent citizens" of Detroit. The Detroit News emphasized that the crackdown was necessary because of the violent crime problem, and briefly acknowledged that the police were questioning and searching some "law-abiding citizens" in the manhunt. But this was unavoidable:

The Detroit News explained that the racial focus of the crash program was necessary, because the killers in the unsolved murders were black men (withouth addressing the race of the victims or suspects in at least a dozen other unsolved murders in the city for which the News had offered no cash awards). The editorial asked "Negroes" to accept this sacrifice, expressed hope that the police would be courteous as they "unavoidably tread on some innocent toes." The editorial also reminded readers that black residents had come to Betty James's aid during the attack and had given the description of the suspect to the police, with the implication that nothing following from these events could possibly be racially discriminatory.

Many residents also wrote to the newspapers expressing their support for the crash program, and a smaller number expressed opposition. In the Free Press above excerpt, several correspondents defended the DPD for protecting the "decent citizen" and pointed out that the suspects were black men, and so the mass round-up was essential and not racially discriminatory. One white liberal criticized the Free Press for constantly emphasizing the race of the murder suspects.

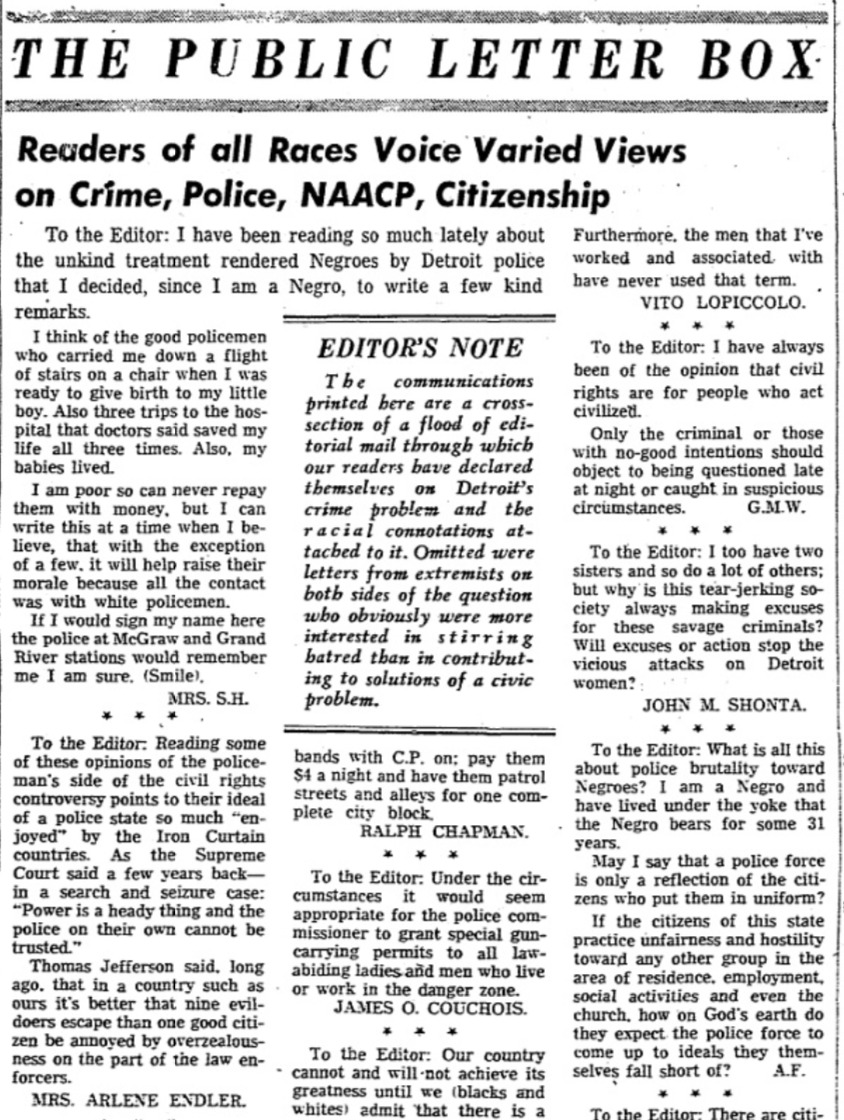

In "The Public Letter Box," excerpted in the gallery below, the Detroit News published a number of racist and reactionary letters from white readers with lines such as:

- "Civil rights are for people who are civilized"

- "Why is this tear-jerking city always making excuses for these savage criminals"

The Detroit News also published a mixture of letters from black residents of Detroit. Several praised the DPD, and others charged the news media with stereotyping and scapegoating "thousands of respectable Negro citizens" based on the actions of a few.

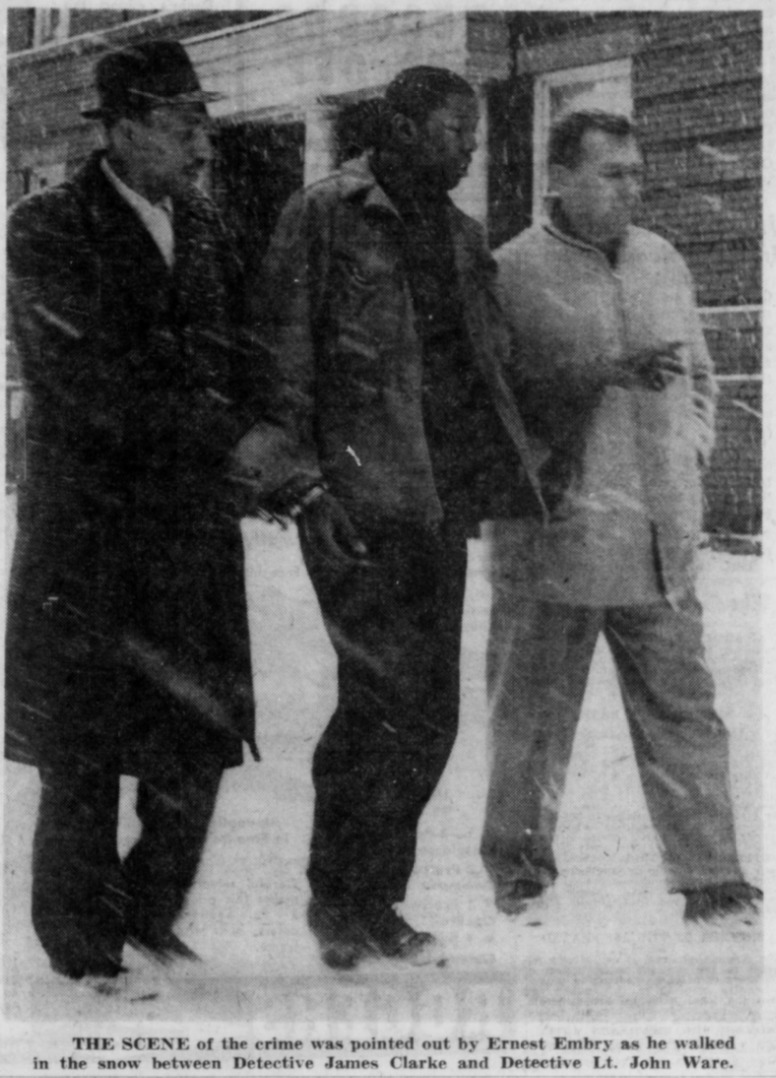

On January 27, 1961, a month after Betty James was murdered, the police identified and arrested her alleged killer, Ernest Embry, a 20-year-old African American male (above right). The Free Press described Embry as a "ragged, dirty young ex-convict who lived in hallways and basements." Embry received a sentence of life in prison. The DPD rewarded the detectives who caught Embry and claimed that their manhunt had solved the crime. The police department did not waste time publicly considering whether the indiscriminate round-up of 1,500 African American men had been necessary to locate Embry, or whether this mass racial profiling had in fact distracted from the crime investigation.

The Jeanette Peters Case

In the above gallery of letters to the editor, several African Americans accused the newspapers of stereotyping all black residents of Detroit as criminals and making it possible for Jeanette Peters to level a false accusation of murder against a "Negro male."

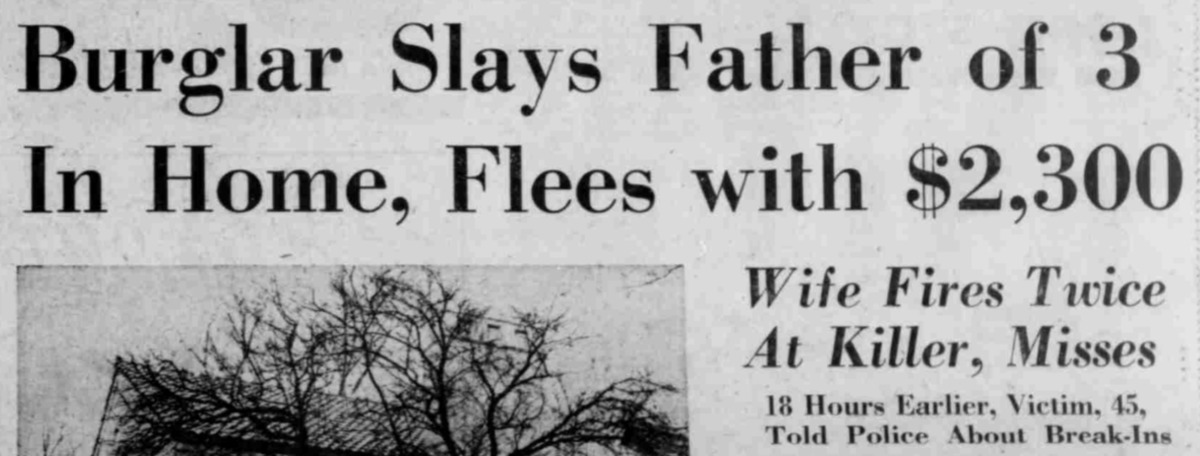

On December 13, 1960, the Detroit Free Press reported an odd story about the murder of Walter Peters, a husband and father who lived in Northwest Detroit, a segregated white area of the city. Jeanette Peters, his wife, reported the crime, allegedly committed by a burglar, and told a harrowing story that seemed almost like a movie. She described how she "chased the killer from the home, fired two shots at him from her husband's gun, but apparently missed him." The Free Press recounted of Mrs. Peters that, "wearing a sweater, skirt and one shoe, she ran screaming after the bandit and onto the front porch, where she fired two shots, aparently missing him." Jeanette Peters described the suspect only as a black male.

Initially, the Walter Peters case seemed to be the fourth unsolved murder in Detroit in just a few weeks in December 1960. It contributed to the media hype of a 'Negro crime wave' and helped justify the DPD's crash program, although Peters did not receive the same attention as that given to the to white women murdered in the streets downtown.

On December 29, 1960, the case was solved. Jeanette Peters admitted to murdering her husband over debt issues. According to Mrs. Peters, the shooting was the climax of a long series of arguments. After the confession, the Free Press gave the case a front-page headline, but then minimal coverage and quickly moved on.

The Jeanette Peters case is another window into the racial politics of Detroit in December 1960. The news media and DPD initially accepted at face value her story framing a black man for the murder of her husband. The story played into another media trope in crime reporting, the invasion of a white middle-class home in a seemingly safe neighborhood by a violent black criminal who had ventured out of the segregated part of Detroit. It was the counterpart to the stories of danger that Marilyn Lou Donohue and Betty James represented, of working-class white women who lived in segregated white neighborhoods but had to venture into a racially mixed zone near downtown for their jobs. The Peters case also fostered fear in the white community and helped generate the political momentum behind the crash program. After Jeanette Peters confessed, the white media and the police department quickly moved on and found no larger truths about crime politics in what seemed like a bizarre and exceptional event. But for black residents, the saga was just more evidence of the racial stereotyping of black criminality in a Jim Crow city.

Sources

Detroit News, December 1960/January 1961

Detroit Free Press, December 1960/January 1961