Operation Backbone

Operation Backbone was the name of an undercover investigation by the FBI into alleged police corruption in the Detroit Police Department (DPD). The operation began in 1990 and ended in May 1991 with the arrest of 11 police officers and 5 civilians. Although Operation Backbone was only one of several outside investigations into corruption in the DPD and Detroit’s city government during the late 1980s and early 1990s, its focus on narcotics corruption and its relative proximity to Mayor Coleman Young made it an attractive subject for the press and one of the most consequential scandals to play out in Detroit during that period. Several elements of the case made it exceptional and easily sensationalized by the news media: it involved undercover agents posing as drug dealers, it hinted at possible criminal activity and complicity on the part of high-ranking police officials including the then head of Detroit’s homicide division, and one of the civilians arrested happened to be Coleman Young’s favorite niece. But the revelation of blatant drug corruption among police officers in Detroit also brought to light broader, deep-seeded problems within the DPD. Narcotics corruption was hardly a new phenomena in Detroit, and the criminal activities of those arrested in Operation Backbone would have sounded quite familiar to anyone who had paid attention to previous scandals involving the DPD. Moreover, several of the figures connected to the scandal had been working in the DPD for many years. Their alleged corruption raises questions about the systemic lack of accountability that allowed “bad apples” to make careers as police officers and rise through the ranks to positions of power, even when there had been earlier signs of their misconduct. Therefore, although exceptional in some respects, the corruption unearthed by Operation Backbone can nevertheless provide important insights about larger patterns of police misconduct in Detroit and the institutional flaws that enabled police criminality.

Operation Backbone officially started in 1990, but its roots date back to the mid 1980s. In order to understand the investigation into corrupt Detroit police officers it is first necessary to examine how the FBI came to suspect that corruption was taking place. The FBI’s path to Operation Backbone is a telling story in its own right, involving a murder coverup, a large-scale drug operation, and a now-famous police informant named Rick Wersche Jr.

Damion Lucas, the Curry Brothers, and “White Boy” Rick Wershe Jr.

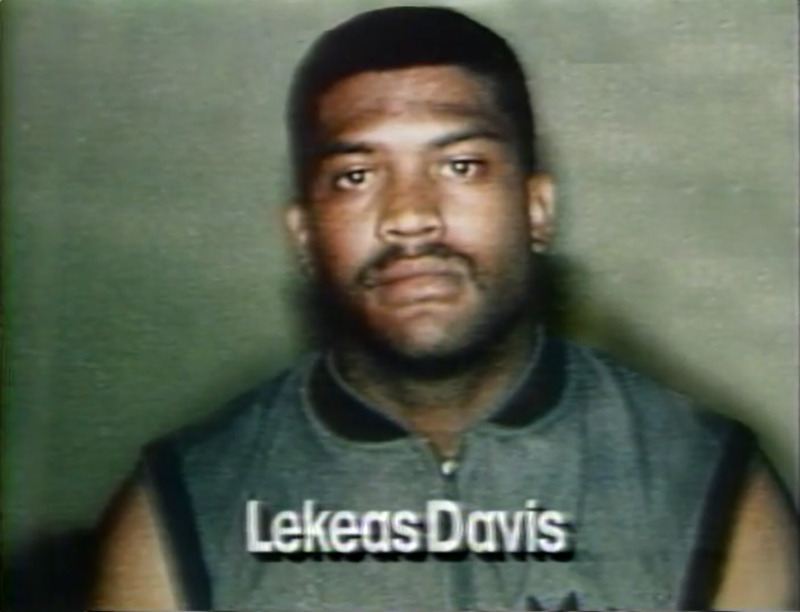

For FBI agents in Detroit, the first hint of corruption within the DPD came with the police response to the murder of 13-year-old Damion Lucas. The story of that murder and the subsequent accusations of a police coverup are detailed at length elsewhere in this exhibit, so a basic summary will suffice here. Damion Lucas was killed accidentally during a drive-by shooting that by all accounts was targeting his uncle, Leon Lucas. Leon Lucas allegedly owed money to Leo Curry, a prominent drug dealer and one of the leaders of the Curry Brothers drug organization. Despite that connection, Detroit homicide investigators instead chose to pursue charges against a man named Lakeas Davis, who had allegedly been seen arguing with Leon Lucas weeks earlier. The decision to arrest Davis and the failure to investigate possible connections to the Curry organization raised flags for FBI agents with knowledge of the case.

One FBI agent in particular, a man named Herman Groman, was especially suspicious of the DPD response to the Damion Lucas murder. During the mid-1980s Groman was involved in a multi-agency investigation into the Curry drug organization and had reason to believe that Leo Curry and his brother Johnny Curry were involved in the murder. Around the time of the Damion Lucas murder the FBI had been able to arrange a wiretap on Johnny Curry’s phone. Using the wiretap, Groman had heard Curry talking to an associate about a recent homicide of a 13-year-old “bringing heat” on his organization. When Detroit police arrested Lakeas Davis, foreclosing the possibility of a serious inquiry into the alleged involvement of the Curry brothers, Groman was dismayed and attempted to contact Detroit homicide to convince the department that it had arrested the wrong suspect. Those in the DPD were not receptive to Groman’s attempts to persuade them to reverse course in the Damion Lucas murder investigation and instead proceeded with their case against Davis.

It was around that time that Groman and others in the Detroit FBI office began to suspect that police corruption was at play in the handling of the Damion Lucas murder. Aside from the DPD’s apparent reluctance to investigate the Curry organization, Groman and the FBI had other reasons to question the relationship between police and the Curry family. Examining Johnny Curry’s phone records prior to the wiretap, Groman found that in the immediate aftermath of the Lucas murder Curry had made several calls to unlisted numbers of two members of the DPD: a Seargant named James “Jimmy” Harris, and the then-head of Detroit’s homicide section, a future Detroit City Council member named Gil Hill.

Even more compelling for Groman and the FBI were the statements of an informant in the Curry narcotics investigation describing a call between Curry and Gil Hill concerning the Lucas killing. The informant was a teenager by the name of Rick Wershe Jr. who had started working as an undercover informant for both the FBI and Detroit police when he was just 14 years old. Wershe told the FBI that he had been in a car with Johnny Curry while Curry had spoken over speakerphone with Gil Hill. According to Wershe, Curry had brought up concerns that his organiation was being targeted as part of the Damion Lucas murder investigation and Hill had assured Curry that he would “take care of it.”

Because of his suspicion of police involvement in covering up the Damion Lucas murder, and because the DPD seemed unresponsive to his suggestions that they investigate the Curry brothers, Agent Herman Groman decided to take his evidence directly to Lakeas Davis’ defence attorney. Eventually, that information helped Davis convince a prosecutor to drop the charges against him. Davis was finally released after spending nine months in jail, and no further charges were ever brought in the Damion Lucas case. Officially, Lucas’ murder remains unsolved to this day.

Profile: "White Boy" Rick Wershe Jr.

The story of the teenage informant who helped alert the FBI to police corruption in the DPD is so remarkable that it has been told in not one, but two separate feature length films: the 2017 documentary White Boy, and the dramatized 2018 production White Boy Rick, featuring Matthew McConaughey as Rick’s father. Even prior to Richard Wershe Jr.’s involvement in Operation Backbone, the teenage drug dealer was a favorite subject for many members of the press in Detroit, who tended to overstate his prominence in the Detroit drug market and gave him the sensationalized nickname “White Boy Rick.” In actuality, Wershe Jr. began working as a DPD and FBI informant prior to his involvement in the drug trade. Rick’s father, Wershe Sr., was himself working as a police informant by the mid-1980s. It was through his father that the FBI and DPD were introduced to Wershe Jr. and began soliciting information from him about suspected drug dealers that he knew from the neighborhood in which he lived. Wershe Jr. was just 14-years-old in 1984 when he started working as an informant for the FBI. According to Wershe Jr., DPD officers and FBI agent Herman Groman soon began asking him to take on a more dangerous role, going undercover to make drug buys from members of the Curry drug organization and selling the product to build trust with the Curry brothers. Groman himself has since confirmed that Detroit police officers instructed Wershe Jr. to make drug buys, although he has denied having a personal role in those operations. After working with the FBI and DPD for several years, law enforcement eventually stopped using Wershe Jr. as an undercover informant. By that time, however, Wershe Jr. was deeply involved in the drug trade and he continued to buy and sell drugs without police supervision. In 1987 Detroit police caught Wershe Jr. with a large package of cocaine. He was prosecuted and convicted under the state of Michigan’s 650-lifer law—a statute that required a mandatory life sentence for anyone convicted of possession of over 650 grams of heroin or cocaine. Although the law was changed in 1998, Wershe Jr. was not granted parole until 2017, having already served nearly 30 years in prison for a non-violent drug offense he committed when he was still a minor.

Groman, for his part, remained deeply concerned about the possibility of high level corruption in the DPD. In 1987 the multi-agency investigation into the Curry drug organization began to close in on its targets. In April of that year a grand jury produced federal indictments leading to the arrests of Johnny and Leo Curry, as well as several of their close associates. The indictments also named, although only as an “unindicted co-conspirator,” Johnny Curry’s wife, a woman named Cathy Volsan-Curry whose uncle was Mayor Coleman Young.

After the arrest of the Curry brothers, Groman met with Johnny Curry and asked him about the suspected police coverup of the Damion Lucas murder. During that meeting, Johnny Curry allegedly told Groman that he had met with Gil Hill shortly after Damion Lucas was killed and given him $10,000 dollars with the understanding that Hill would protect the Curry organization. However, when Groman asked Curry to record the story in an affidavit, Curry refused, claiming that the meeting he had previously described never took place and that there had never been a direct quid pro quo between himself and Gil Hill. Convinced that police corruption had compromised the Damion Lucas case, yet unable to prove it, Groman soon transferred to the public corruption unit of the Detroit FBI. It was there that he helped launch an undercover investigation into the police corruption in Detroit. Groman and his fellow agents named their investigation Operation Backbone.

The Undercover Operation

Operation Backbone began in earnest in September 1990. The plan was to use an undercover FBI agent, posing as a major Miami drug trafficker, to root out police corruption within the DPD. To kickstart the investigation the FBI once again relied on Rick Wershe Jr., who by then was incarcerated, having received a life sentence for possession of over 650 grams of cocaine in 1988. The FBI asked Wershe Jr. to introduce their undercover agent to Cathy Volsan-Curry, who they suspected of arranging police protection for the Curry organization. Wershe Jr. agreed and set up the meeting. Just as the FBI had suspected, Volsan-Curry told the undercover agent, whose real name was Mike Castro, that she could use her connections in the DPD to provide police protection for him to bring cash and drugs into Detroit.

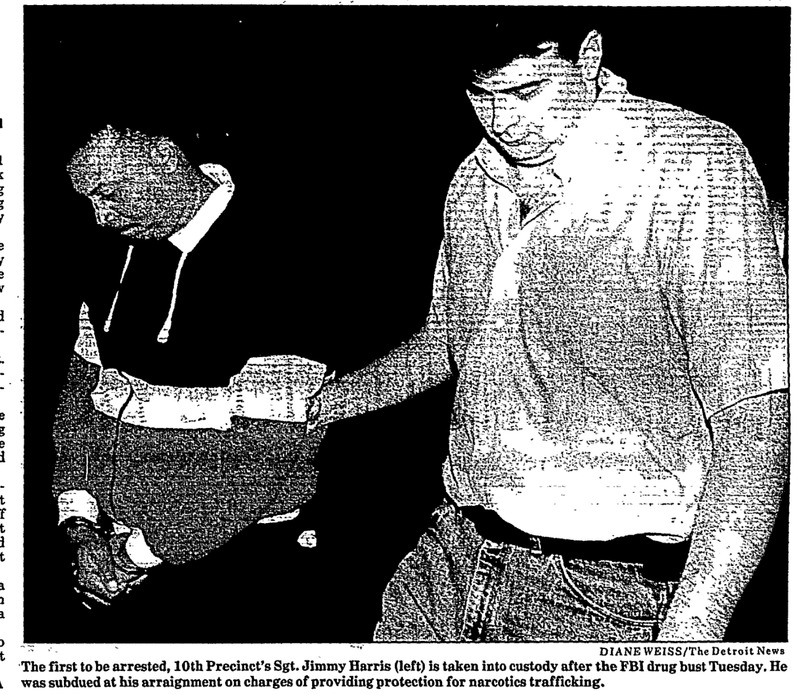

Volsan-Curry soon introduced Castro to her father Willie Volsan, who was the Mayor’s brother-in-law. Willie Volsan proceeded to arrange for DPD Sergeant James Harris, along with several other DPD officers, to provide Castro with a police escort as he brought briefcases full of supposed drug money from the Detroit airport to a local bank for “laundering.” The FBI and Castro made four successful runs pretending to launder drug money, each time paying the corrupt police escort upwards of $5,000 for their illicit services. Eventually, the investigators in Operation Backbone decided to see if the officers would take things a step further.

Undercover FBI agent Mike Castro invited Willie Volsan and James Harris to meet with him in Miami. There, inside a lavish yacht fitted with hidden cameras and recording equipment, Castro explained to Harris and Volsan that he wanted to ship dozens of kilos of cocaine into Detroit using their police protection to ensure safe delivery and prevent interference from law enforcement. Volsan and Harris agreed and before long the pair helped agent Castro bring multiple shipments of what they thought was cocaine into Detroit through the Detroit airport.

Herman Groman, Mike Castro, and others in Operation Backbone still believed that the corruption went deeper than what they had been able to uncover at that point in their investigation. Contributing to that belief, Willie Volsan reportedly bragged throughout his involvement in the operation about his close relationship with Gil Hill, the head of the DPD homicide section. The FBI made two unsuccessful attempts to prove that Gil Hill was also corrupt. First, through a meeting with Willie Volsan, they attempted to bring Gil Hill on board with their phony drug operation. Although Hill hardly acted surprised by the request, telling agent Castro he would consider it, he ultimately did not take the bait. Then, towards the end of the investigation, the FBI tried to convince James Harris to flip, asking him to wear a wire and collect evidence of corruption among Gil Hill and other higher-ups. Harris refused to do so. Without any promising options available to extend the investigation the FBI concluded Operation Bakbone with the arrest of 11 corrupt police officers and 5 civilians.

James Harris was, of course, one of the police officers arrested and convicted as a result of the probe. Harris was sentenced to 30 years in prison, but was released in 2008 after receiving a commutation from President George Bush. After his release, Harris participated in an interview with the creators of the Crimetown podcast to share his experience with Operation Backbone. When asked if he regretted his refusal to cooperate with the FBI investigation Harris had this to say: “I’m a loyal person. If I had cooperated then I’d have to bring people in like the Mayor, his family. And then how could I come back to Detroit and face these people? You know they’d all remember and say ‘goddamn Jimmy Harris told ‘em, testified against the Mayor and police officers and other people’.”

Crimetown: Police Sergeant Jimmy Harris Plans Drug Shipments on Undercover FBI Video from Gimlet on Vimeo.

Profile: James “Jimmy” Harris

Operation Backbone was not the first time that James Harris was involved in a major public scandal connected to his work in the Detroit Police Department. Just a few years after Harris first joined the police force in 1968 he volunteered to work as an undercover officer in the DPD’s STRESS program, a controversial plainclothes police unit whose members killed at least 22 Detroit civilians during its three years of operation (1971-1973). Harris was involved in one of the most infamous and most violent incidents involving STRESS officers. In March 1972, a group of STRESS officers conducted an impromptu raid on an apartment filled with off-duty Wayne County Sheriff’s Deputies. Both groups of law enforcement officers apparently mistook each other for criminals and a gun battle broke out between them resulting in the death of one of the Sheriff’s Deputies and the permanent paralysis of another. Far from a bystander or passive participant in this incident, James Harris was one of the initiators of the violence, and was likely responsible for firing the first gunshots. In the aftermath of the episode, which came to be known as the “Rochester Street Massacre," some anti-STRESS activists speculated that the incident may have been a result of two groups of corrupt law enforcement officers competing for access to the city's lucrative drug trade. Although James Harris and two other STRESS officers were charged with assault with intent to kill for their actions during the shootout, the Wayne County Prosecutors' case against them was notably weaker than it could have been given the evidence and a jury found all three officers not guilty. Following the acquittal, all three officers continued working for the DPD.

James Harris actually moved up in the ranks after the Rochester Street Massacre. By 1975 Harris had been promoted to detective and was the head of a squad within the homicide division of the DPD. Later, Harris began working for Mayor Coleman Young’s security detail. His service for the Mayor paid off in 1986 when he was promoted to the rank of Sergeant. Although standard procedure in the DPD awarded promotions based on test scores from competitive written and oral exams, Harris was given his promotion directly on the recommendation of Chief William Hart, who cited Harris’ past work for the Mayor as the reason for his recommendation.

There are other reasons to belive that James Harris’ actions during Operation Backbone were not his first time engaging in corruption. Most concretely, Harris’ connections to the Curry drug organization had been one of the original factors that led the Detroit FBI to suspect a coverup of the Damion Lucas murder and corruption within the DPD. In addition to the phone call made from Johnny Curry’s phone to Harris’ unlisted telephone number shortly after the Lucas murder, a police raid of Johnny Curry’s home had produced a card listing multiple telephone numbers for both Gil Hill and James Harris. In the video of Harris’ meeting with undercover FBI agent Mike Castro in Miami, Harris appears relaxed and eager while engaging with people he believed to be major drug traffickers. Moreover, Harris demonstrated was the primary link between the undercover FBI agents and the other corrupt officers who helped protect “drug shipments” during Operation Backbone. Harris’ apparent comfort with corrupt activities and his connections to other corrupt officers suggest that his experience with illicit activities may have been more extensive than he has admitted.

Systemic Roots of Narcotics Corruption

Although Operation Backbone was heavily sensationalized by the press, the involvement of Detroit police in narcotics corruption was by no means new to Detroit. The history of drug corruption among Detroit police goes as far back as the mid 1950s, when a handful of current and former DPD narcotics officers were convicted for working with a massive heroin trafficking network. One of those officers, a decorated narcotics cop named Henry Marzette, later became one of Detroit’s first major drug kingpins, organizing massive narcotics transactions and other illegal activities until his death in 1972. In the early 1970s, an internal investigation of the DPD uncovered widespread drug corruption in the 10th Precinct, despite investigators reporting major obstruction from others within the DPD. During the 1980s and 1990s, as the War on Drugs intensified in cities across the United States, narcotics corruption in Detroit seemed to flourish. In 1988 and 1989, the Detroit News ran several stories noting increases in high profile police crimes, many of which involved drugs and drug corruption. For Detroiters who regularly read the local news, Operation Backbone would not have been the first time they heard about DPD officers involved in the drug trade.

Why was drug corruption such a ubiquitous feature of policing in Detroit during the second half of the 20th century? One important fact to note when considering this question is that the problem of police narcotics corruption was not unique to Detroit. Many other major cities at the time, including New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles, to name a few, also had major scandals featuring police involvement in the drug trade during that same period. Some scholars, including historians Lisa McGirr and Eric Schneider, have argued that the act of policing vice markets—such as narcotics markets—itself tends to lead to corruption. This argument certainly holds some weight in the case of Detroit, with many of the city’s major corruption scandals having centered around the drug trade. Yet the lucrative nature of vice markets and the countless opportunities for corruption available to those tasked with enforcing them, only goes so far in explaining the persistence and extent of drug corruption within the DPD. As the corruption of James Harris and the suspected corruption of Gil Hill makes clear, illicit police activities were in no way limited to officers specifically tasked with narcotics enforcement. What other factors might help explain the pattern of police crime and corruption that plagued the DPD for decades?

Another explanation of why the scourge of drug corruption was never fully resolved in the DPD is that police officers enjoyed an astonishing lack of accountability. Internal investigations into police corruption, such as the major inquiry into widespread drug corruption during the early 1970s, were frequently stonewalled by regular officers and police higher-ups alike. The police culture in the DPD was itself a major barrier to proper police accountability. Officers faced being socially ostracized and risked their career prospects if they chose to report the misconduct of their colleagues. The tendency to overlook police misconduct was not limited to the rank and file officers, or even to members of the DPD itself. Wayne County prosecutors, for example, were also reluctant to seriously pursue charges against police officers, as they showed in the aftermath of the “Rochester St. Massacre.” Compounding these issues was a powerful, primarily white police union and a strong pro-police political base in city politics. Those barriers made it hard for anyone—including Mayor Coleman Young, who initially ran on a platform of police reform—to make meaningful changes that could have promoted accountability within the department.

As a result of the impunity enjoyed by many DPD officers, problem officers were allowed to continue within the department and corruption and misconduct became chronic issues. The case of James Harris is representative of the worst consequences of the lack of police accountability in Detroit. Early in his career Harris’ actions initiated the “Rochester St. Massacre,” a deadly shooting between undercover DPD officers and a group of off-duty Sheriff's deputies. Even after Harris’ acquittal in the criminal case resulting from the incident, the DPD could have still fired Harris for demonstrating a lack of restraint and judgment. Instead, Harris continued on the force. Not only did he retain his position as a police officer, he was soon granted a promotion. The lack of accountability for Harris put him in a position to abuse his power to help drug traffickers launder money and smuggle cocaine into Detroit. For countless other problem officers, a lack of accountability similarly enabled continued misconduct and corruption. The outside investigations into Detroit corruption during the late 1980s and 1990s, including Operation Backbone, were a late and insufficient response to a systemic lack of accountability within the DPD that had allowed misconduct and corruption to fester for decades.

Sources:

Detroit News, News Bank - Access World News.

Detroit Free Press, ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

Gimlet Inc. Crimetown, Episode 8, "Operation Backbone."

Gimlet Inc. Crimetown, Episode 7, "Who Killed Damion Lucas?"

White Boy (2017), directed by Shawn Rech (Transition Studios, 2017).

Interview of Herman Groman by Jerri Williams, September 2017, FBI Retired Case File Review, Episode 085, Spotify.