Outside Investigations

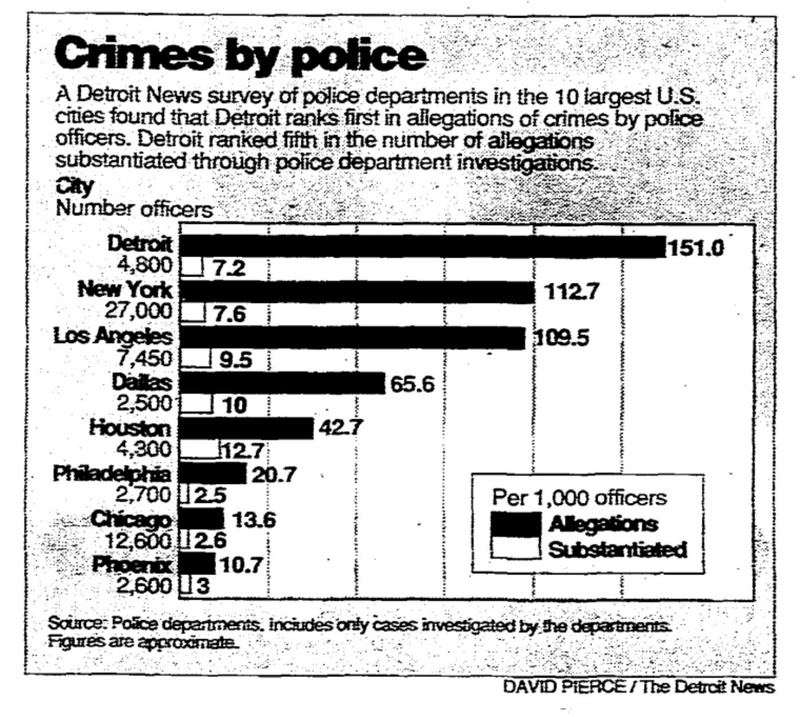

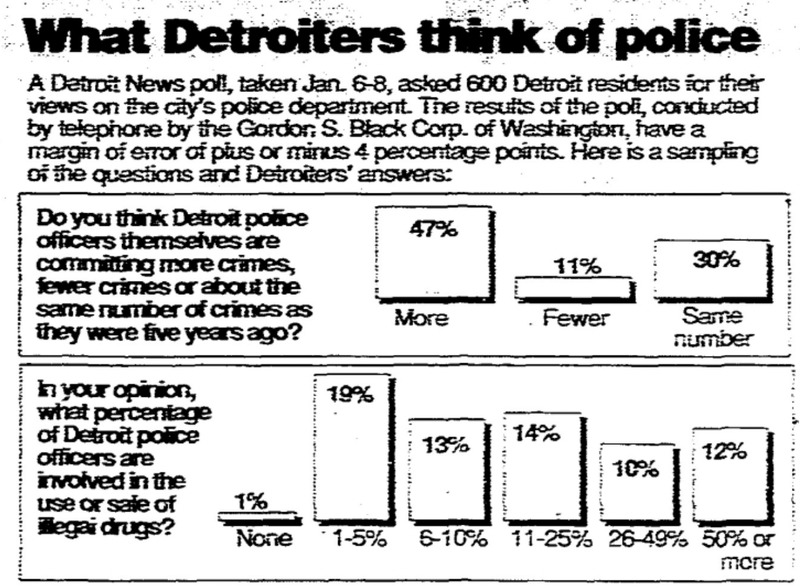

During the late 1980s and the early 1990s, just as the War on Drugs was reaching its fever pitch, official corruption was flourishing in Detroit, especially in the Detroit Police Department (DPD). During the mid 1980s the rate of criminal complaints against DPD officers skyrocketed, jumping from 497 formal complaints in 1985 to 725 just two years later. Around the same time, a flurry of scandals involving high profile crimes committed by police rocked the DPD. As an article in a Detroit News series noted in 1989, many of those crimes involved narcotics and drug corruption: “Detroit officers have been accused of planning the murder of a drug dealer on behalf of another drug dealer, accepting payoffs from dealers, and stealing drugs and drug money in the past two years.” The article went on to list even more recent incidents:

Although the Detroit News directed blame for the increased number of serious police crimes on a dramatic increase in the hiring of new, inexperienced officers during the mid 1980s, the high frequency of drug related offenses and the use of increased funds from the federal War on Drugs to enable that massive hiring wave suggest that the escalation of narcotics policing also contributed to the heightened levels of police corruption and misconduct experienced in Detroit at the time.

Rank-and-file police officers were not the only source of corruption within the DPD and city government. The late 1980s and early 1990s also featured several major scandals and external corruption investigations involving higher-ups in the DPD and in Mayor Coleman Young’s administration. Those scandals would come crashing down over the course of the early 1990s and the controversy they spurred was likely a factor in Young’s decision not to run for a sixth term as Mayor, helping to end an era in Detroit politics that had persevered for twenty turbulent years.

Coleman Young himself had long been a target of investigations and surveillance by the FBI and other federal authorities. Records from FBI files on Young indicate that the agency’s initial interest in him was less based on actual evidence of criminality as it was a response to on his political leanings, specifically his leftist views and, later, his involvement with union organizing as a leader in the National Negro Labor Council during the early 1950s. After Young was elected Mayor of Detroit in 1974, federal agencies seemed to step up their efforts to find dirt on Young, an emergent symbol of Black political leadership. During his first two years in office Young was a subject in separate investigations into an investment he held in a housing development project and his connections to DPD Deputy Chief Frank Blount, who had allegedly been receiving payouts from drug dealers. Young was never charged in either case—even Blount was never indicted although he was removed from the DPD—and many commentators, including the U.S. prosecutor in Detroit at the time of the Blount affair, speculated that the federal government was blindly fishing for evidence of corruption involving Young.

During the 1980s several cases brought federal investigators much closer to Coleman Young and his allies in city government. In 1981 an investigation into a waste disposal company, which had bribed a city official in order to secure a lucrative city contract, led to direct surveillance of Young, including wiretaps on his phone conversations. Although investigators suspected Young’s involvement in the crime (or at least his prior knowledge of the bribe), the evidence ultimately fell short of what they felt was necessary to secure a conviction, and charges were never brought against Young in the case.

In the mid 1980s yet another Deputy Police Chief in Detroit, a man named Kenneth Weiner, became entangled in criminal investigations, this time related to illicit financial dealings and allegations of official corruption in the city government. Once again, the investigation brought authorities within striking distance of Coleman Young. A consulting company owned by Young was found to have helped facilitate the sale of gold Kruggerands—coins minted by South Africa’s white apartheid regime—which were connected to a ponzi scheme organized by Kenneth Weiner. Despite two years spent cooperating with authorities in their attempts to substantiate corruption allegations against Young and other Detroit officials, Weiner was ultimately convicted of financial crimes and sentenced to time in prison. Young escaped any form of criminal indictment.

Even in the absence of formal charges against Coleman Young, the repeated criminal investigations into his activities and those in his political orbit took their toll on his reputation. During the early years of the 1990s two additional scandals, both tied to policing and police corruption, brought additional scrutiny to the Mayor and a crushing blow to his public standing in Detroit. First, in February 1991, long-time Police Chief William Hart, appointed by Young in 1976, was indicted of embezzlement for stealing over two million dollars from a secret police fund intended for undercover narcotics operations. Then, less than four months later, the FBI revealed the results of an undercover investigation into police corruption in the DPD, that had been sparked by lingering questions surrounding the murder of 13-year-old Damion Lucas. That revelation included the arrest of 11 Detroit police officers and several civilians. Among those arrested were the Mayor’s niece, Cathy Volsan Curry, and a police Sergeant who had been directly promoted by Coleman Young and had worked on Young’s security detail. While neither of these cases led to charges against Young, they certainly did not reflect well on his administration. In the aftermath of these scandals Young announced he would not be seeking a sixth term.

Coleman Young appears in this clip from a 1990 ABC Primetime Live special on Detroit in which he is confronted about the accusations of corruption surrounding his administration at the time.

Corruption in Detroit and in the DPD by no means began or ended with Coleman Young's administration, and given the lack of any criminal indictment against him it is difficult to pin down what, if any, role he played in fostering, permitting, or participating in corruption in Detroit. However, the multiple outside investigations that federal authorities used to investigate accusations of corruption against Young provide an excellent opportunity to examine patterns of misconduct, corruption, and criminality within the DPD. This section provides the details of several of these investigations not as an inquiry into the alleged criminal activities of individual actors such as Mayor Coleman Young or Chief William Hart, but as a reflection on the broader systemic forces that allowed corruption to flourish within the Detroit Police Department. Outside investigations such as those that surrounded Coleman Young give crucial clues as to the practices, policies, and elements of police culture that contributed to police corruption in Detroit and offer hints as to how cities might work to avoid such problems in the future.

ABC Primetime Live, "Detroit's Agony," Nov. 8, 1990, accessed Oct. 12, 2022, YouTube.

Detroit News, News Bank - Access World News.

Detroit Free Press, ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

Gimlet Inc. Crimetown, Episode 8, "Operation Backbone."