Unjust Police Brutality: Robert F. Mitchell, 1957

The Robert F. Mitchell case of January 1957 exemplifies a pattern in police brutality in the city of Detroit during the civil rights era: police officers brutally beat an African American man, and then claim self-defense because he was allegedly resisting arrest. The victim then files a formal complaint, and so the DPD's Trial Board investigates the case and exonerates the white officers, taking their word over the testimony of an African American civilian as well as African American witnesses, almost always. The Detroit Free Press, the city's leading newspaper, covered this type of story in a limited fashion and mainly from the perspective of the DPD. The Michigan Chronicle, Detroit's main African American newspaper, reported on the case extensively with numerous front-page articles, detailed information from the perspective of the victim, and extensive documentary evidence of an official cover-up by the Detroit Police Department.

Mitchell, a 31-year-old African American businessman from Ohio, graduated from Ohio State University and then Wayne State Law School. He was a bar owner in Detroit, a husband, and the father of a two-year-old. He was a member of the Cotillion Club, an elite group of black civic and business leaders who promoted better police-community relations. He had no criminal record before the incident.

What Happened?

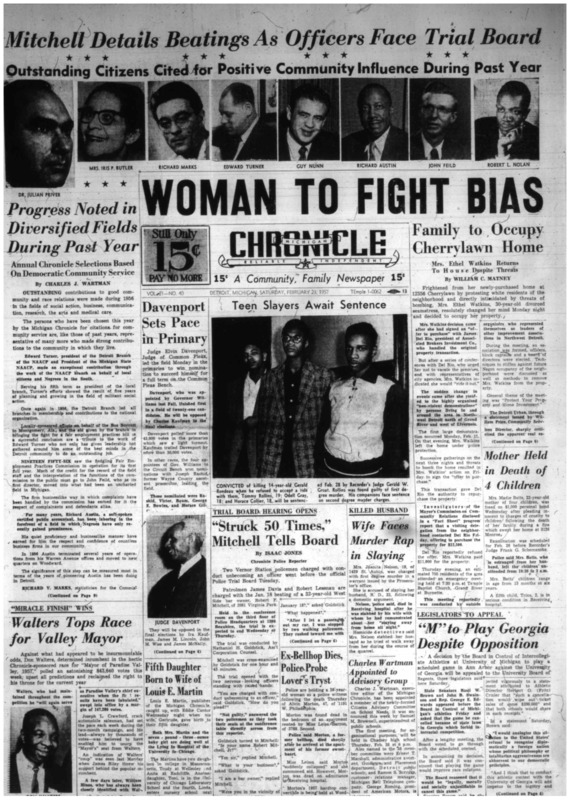

According to Robert Mitchell, two Detroit police officers stopped him for no legitimate reason and brutally beat him. Around 9:15 p.m. on Monday, January 18, 1957, Vernor Station patrolmen James R. Davis and Robert J. Lessnau* detained Mitchell "without provocation" as he dropped someone off from his vehicle. The officers asked for Mitchell's credentials, which he willingly provided. The officers questioned if a roll of change in his car was because he was an illegal numbers man (gambling), which Mitchell denied, saying it was for his business. The officers then asked him to step out of the car in order to search both the car and his person. Mitchell complied at first, but then, as a crowd gathered, he asked to be searched at the station because he did not like being treated like a criminal in public. Mitchell said, "They treated me like I was a known hoodlum." The officers proceeded to beat him brutally with their night sticks, striking him around 50 times, while cursing him and calling him racial epithets. Mitchell sustained terrible injuries and sought treatment at Receiving Hospital. He suffered multiple bruises on his scalp and forehead, a scalp laceration that required up to 10 stitches, the loss of a tooth, and other bruises on his arm and leg.

Following the incident, Mitchell filed a complaint to the DPD and also to the FBI, under a federal statute providing a $1,000 fine and/or a year in jail for a law enforcement officer who deprived a citizen of his constitutional rights without due process of law. Mitchell’s complaint, in combination with the media publicity, prompted Mayor Louis Miriani and Police Commissioner Edward S. Piggins to request an internal investigation by the Trial Board. (The FBI did nothing).

The officers told a very different story. According to Davis and Lessnau, they pulled Mitchell over for a headlight violation. They claimed Mitchell did not cooperate with their lawful requests. Lessnau went to his patrol car, called the police station, and learned that Mitchell did not have a police record. When Lessnau returned, he asked to search Mitchell and the car, and Mitchell refused. The officers claim Lessnau put his hands into the car to try to get Mitchell out of the vehicle, at which point, Mitchell started driving away and dragged the officer 20 or 30 feet before he was forced to stop. They did not explain how Mitchell was forced to stop. They claimed Mitchell then struck Lessnau and seized Davis’s coat, as they were taking him out of the car. According to the patrolmen, they then legally used their night sticks to control Mitchell. Mitchell was charged with assault, resisting arrest, and obstruction of a police officer performing his duty.

Civil Rights Protests and Dismissed Charges

Mitchell’s case drew widespread attention after he filed the FBI complaint and African American civic groups took up his cause. Twelve African American groups organized protests following the DPD's criminal charges against Mitchell. Around 100 civic leaders formed the Detroit Citizens Committee and demanded that the DPD conduct a full investigation. More than twenty-five African Americans, many of whom were Mitchell's fraternity brothers from Ohio State University, sent telegrams to the Police Department regarding the incident, asking for witnesses and defending Mitchell's character.

Due to this "community interest," Mayor Louis Miriani requested that Commissioner Piggins convene a Trial Board inquiry. Other politicians, such as councilman William Rogell, opposed the internal investigation and said that the "the boys in blue take a lot of beating from cop-haters." The Detroit Free Press claimed, with little acknowledgment of the racial context, that such an experience "could happen to anyone."

The Detroit Commission on Community Relations (DCCR), a biracial agency with responsibility for peaceful race relations, also hosted a community meeting to discuss the situation and gathered evidence for an investigation (right).

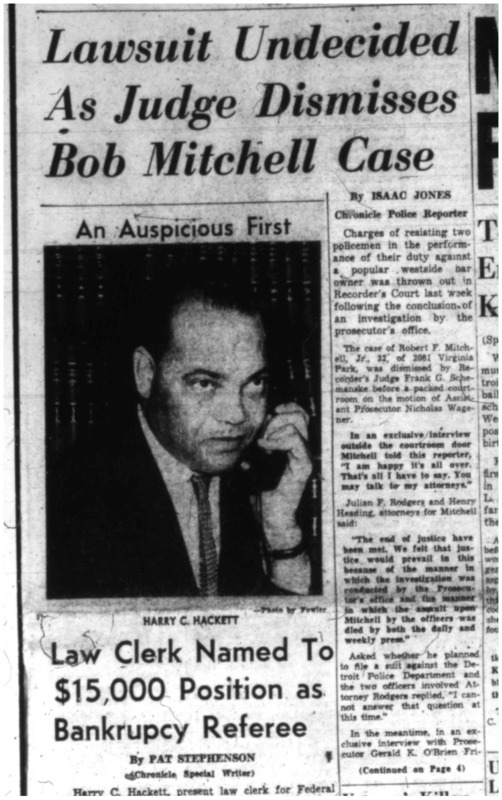

On February 7, at the request of the Wayne County prosecutor, a judge dismissed the criminal charges against Robert Mitchell. Judge Frank Schemanske ruled that "the story the eye witnesses tell is certainly not in accordance with the representation made by the Police Department in their write up." The prosecutor, in a very unusual development, expressed public doubt about the official police account and recommended that the DPD consider discipline of the officers involved.

Note: the prosecutor never indicated any inclination to consider criminal charges against the DPD officers, even given the eyewitness testimony that supported Mitchell's account. A police officer who assaults a civilian without cause has committed a felony, filing a false official report is also illegal, and testifying to a false story is perjury.

DPD Trial Board Investigation

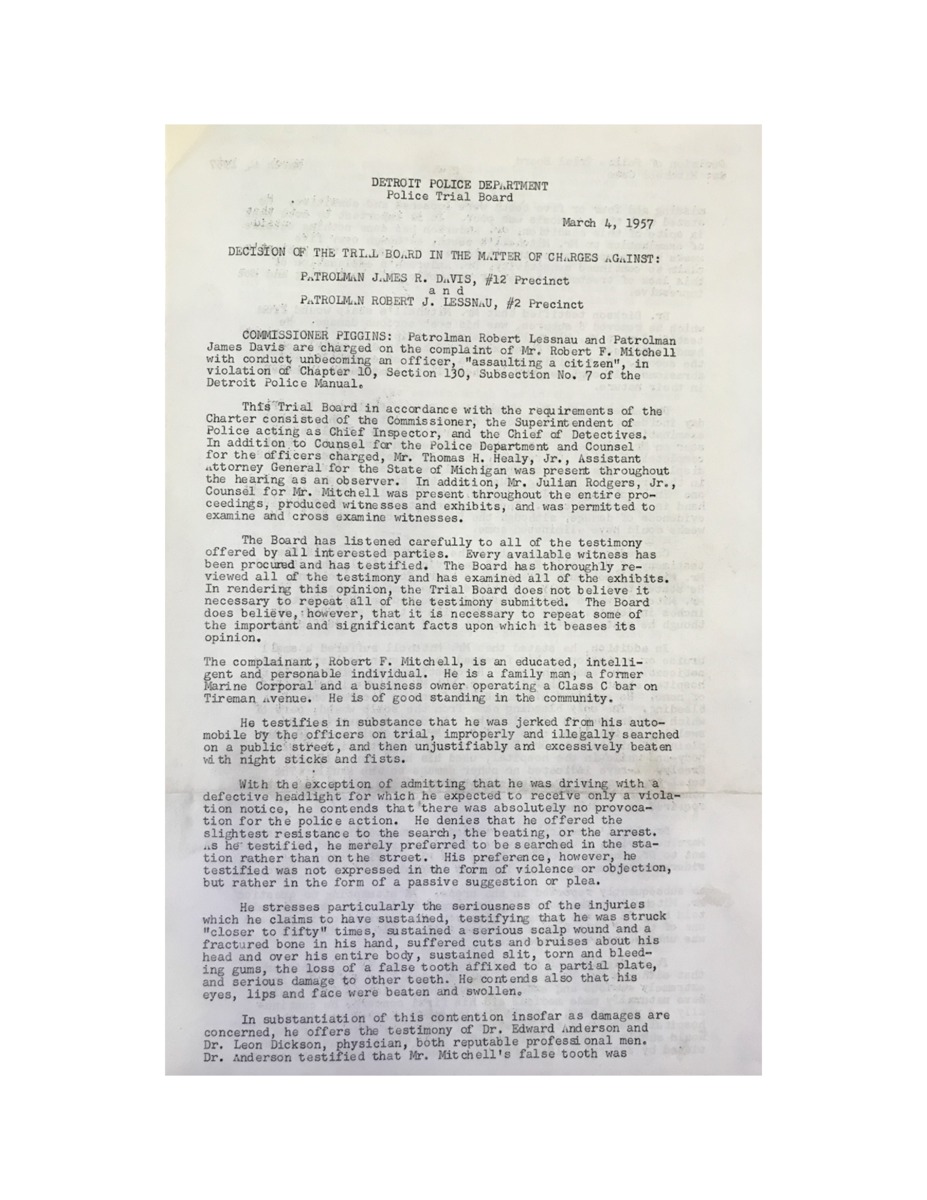

The Police Trial Board, chaired by Commissioner Piggins, heard from Michell and the same eyewitnesses who had convinced the prosecutor to drop charges and then exonerated Patrolman Lessnau and Patrolman Davis on March 4, 1957.

Robert Mitchell testified to the Trial Board about the incident in vivid detail:

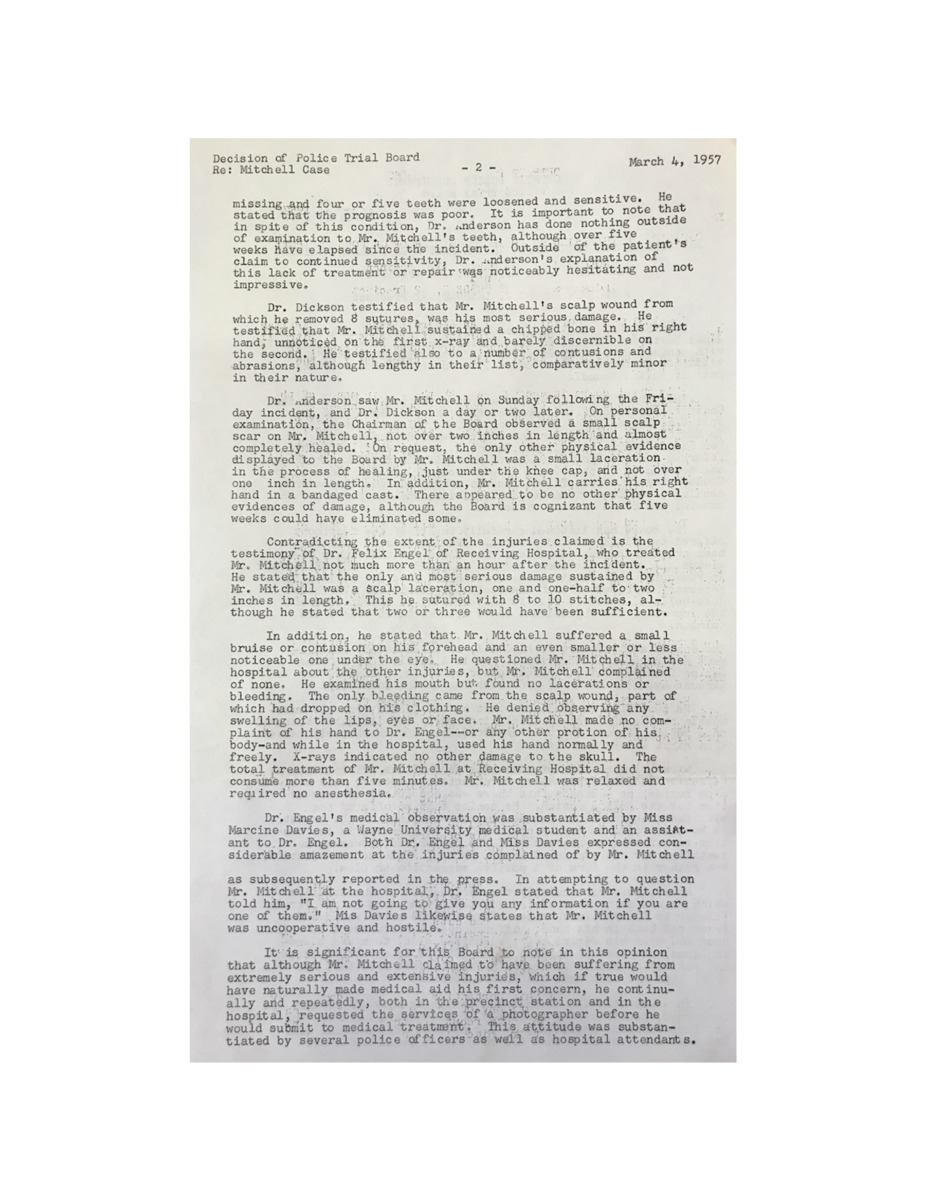

The Trial Board reached its decision by first questioning the severity of Mitchell’s injuries. They argued that the initial doctor who treated Mitchell at Receiving Hospital did not believe his injuries were as serious as other (African American) doctors who provided a second opinion days later. (Reading between the lines, it is clear that Mitchell did not trust the white doctors at Receiving Hospital to fairly document injuries attributed to police brutality). The Trial Board further contended that Mitchell acted with ulterior motives by having a photographer document his injuries before medical treatment, and that he was seeking to make a political point about the police. Effectively, the Trial Board report implied that Mitchell was seeking to frame the two police officers.

The Trial Board also asserted that the eyewitness accounts, all from African Americans, were inconsistent, because some said the police beat Mitchell in a doorway, and others said the police beat him in the street. (According to Mitchell's testimony, the officers beat him in both locations). Based on these alleged discrepancies, the Trial Board criticized the Wayne County prosecutor for agreeing to the dismissal of the charges against Mitchell.

The Trial Board instead believed the two white police officers, Robert Lessnau and James Davis, who claimed that Mitchell initiated the confrontation by punching Lessnau and that he was "resentful, uncooperative, belligerent, violent, and provoked the incident." The report admitted that a law-abiding citizen who had done nothing wrong might resent being searched by police officers on the street. But it found that the officers' decision to stop and search Mitchell, which escalated the confrontation, was legal, based on a convoluted rationale that someone with a similar name had a criminal record. The Trial Board report found the officers not guilty and emphasized its decision was based on the neutral facts alone.

Read the full Trial Board report rejecting Robert Mitchell's complaint in the gallery below.

The Trial Board report, written by three white male police executives, reveals the inherent racial bias within the Detroit Police Department and how ineffective the notion of "police policing themselves" really was. The report accepted the word of the white officers, rejected the testimony of all of the African American eyewitnesses (right), and jumped through multiple hoops to question the motives and discredit the story of Robert Mitchell. The report scrutinized and highlighted every possible inconsistency in the testimony of the African American witnesses and victim, and subjected the testimony and actions of Officers Lessnau and Davis to none of the same rigorous analysis. The report was a whitewash of police brutality, in an investigation designed from the outset to exonerate the police. Its claims to be fair, neutral, and objective were hollow.

In the conclusion of the report, the Trial Board stated that the Detroit Police Department would never "condone the use of excessive force or brutality." The Trial Board, chaired by Police Commissioner Piggins, then rhapsodized about the hardships of being a police officer and presented Robert Lessnau and James Davis as the real victims of the events in question:

Community Reaction

Unlike the Detroit Free Press, the Michigan Chronicle reported the frustration and disappointment among Detroit's African American citizens regarding the outcome of the DPD invesigation. The Chronicle quoted one Detroiter as saying, "Many Negro citizens, no doubt, because of their experience will not be persuaded that the truth was allowed to prevail." Ernest Shell, the chairman of the Detroit Citizens Committee, stated that "we had earnestly hoped the Trial Board would recognize the broad community significance of this unfortunate occurence and would make at least an effort to show its disapproval of brutality by police officers." To these black leaders and residents, the Mitchell case was not a run of the mill episode of police brutality, because it involved an exemplary citizen and businessman, with multiple university degrees and elite civic standing, with several eyewitnesses who supported his account. They had hoped and believed that the case would provide an opportunity for the police department to treat Detroit citizens equally.

Read the Michigan Chronicle's extensive coverage of the Mitchell investigation in the gallery below. After the exoneration, the Chronicle editorialized:

Assessment

Robert Mitchell's experience of racial criminalization and victimization by DPD officers was typical for African Americans in Detroit during the late 1950s, as the NAACP documented in its campaign against police brutality. (The main differences in his case are the degree of media coverage and that the DPD actually investigated his complaint, which owed to his standing as a repected businessman). Police officers practiced racial profiling and often pulled over African American motorists for minor infractions or for no cause at all. This often led to major escalations and incidents of brutality, especially when a civilian asserted the constitutional right to not be searched or detained without cause. Officers routinely arrested and charged civilians whom they mistreated, which was an effective if illegal way to discredit their complaints by criminalizing their actions. Police officers almost never suffered any consequences for criminal assaults on African American civilians, even when eyewitnesses corroborated their stories.

Soon after the Robert Mitchell case ended, civil rights groups in Detroit began calling for a civilian review board to monitor the police department and investigate officer brutality and misconduct. The DPD and a succession of mayoral administrations, both conservative and liberal, resisted this reform and insisted that the police could police themselves. That story is next.

*In 1961, an African American citizen filed a second complaint against Patrolman Lessnau. Officers Theodore Hart, Robert Lessnau, Robert Hayes, and Richard Bylicki entered Willie Tyner's home without a warrant while his wife and children were home and inquired if Tyner had a gun. They searched his home and car and gave no reason why. They attempted to force him to leave his identifcation at the residence. They arrested him and took his car. He was detained at the station but was never fingerprinted or charged with any crime.

Sources:

Detroit Free Press, January 22, 1957

Detroit Free Press, February 8, 1957

Detroit Free Press, February 26, 1957

Michigan Chronicle, January-March, 1957

Mayor’s Papers 1957, Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library

American Civil Liberties Union of Michigan/ Metropolitan Detroit Branch Collection, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University