Misconduct and Cover-Ups

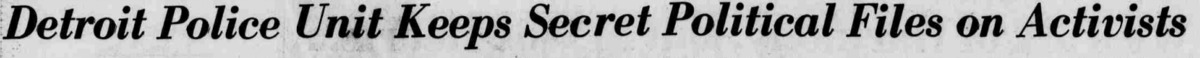

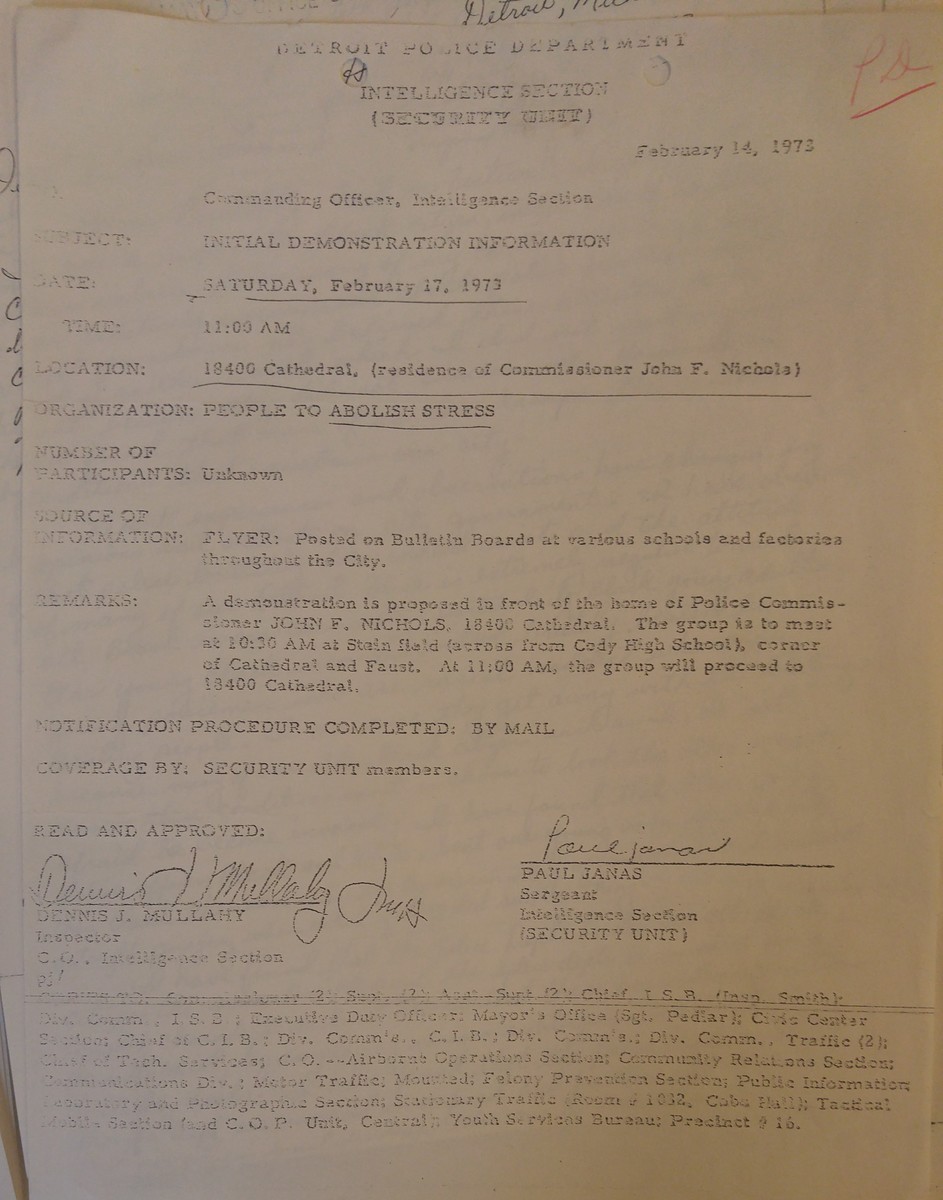

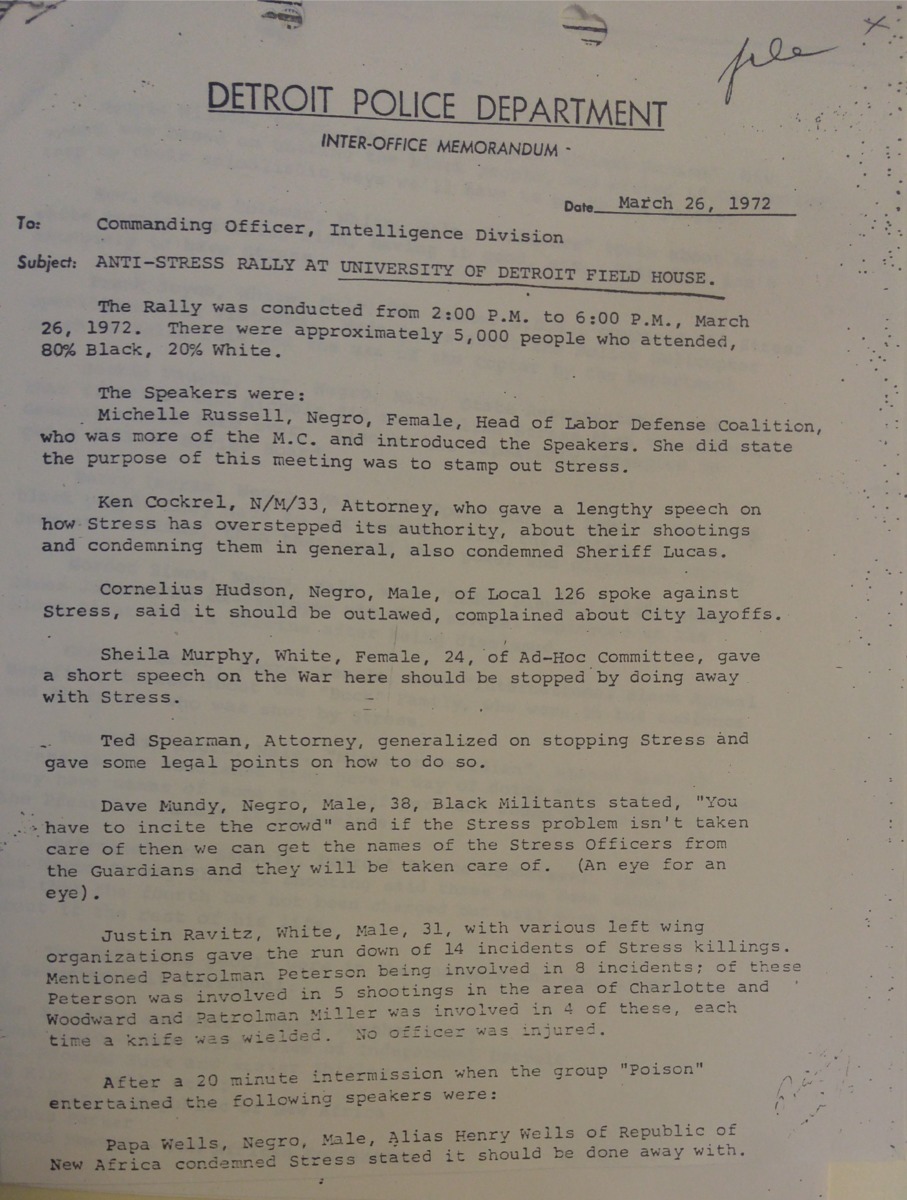

Political Surveillance

The Detroit Police Department paid close attention to radical leftist and also moderate community organizing that took place at this time. Throughout the early 1970’s, groups like the Detroit Urban League, NAACP, League of Revolutionary Black Workers, and the Labor Defense Coalition were holding meetings and forming coalitions in response to misconduct and corruption on behalf of the DPD. Much like the decoy officers of the STRESS unit, DPD officers were going undercover as radical activists at almost every one of these organizations’ meetings and community organizing efforts--acting as informants, taking down the names of every person in attendance and sometimes recording what was said word-for-word. No anti-STRESS organizers or police reform and oversight advocates were exempt from the surveillance practices of DPD. In fact, many recorded instances of anti-police sentiment or violence at these meetings was first incited by the DPD informants.

This surveillance was not unique to Detroit. The practice of police surveillance against leftist black political organizations has its roots in the federal government. Beginning in the mid-1950s, the FBI introduced a program called COINTELPRO to spy on supposed communists and communist groups in the U.S. Shortly after the Detroit Uprising in 1967, FBI director J. Edgar Hoover established a "Black Nationalist Hate Groups" category within COINTELPRO. The FBI coordinated with local law enforcement in major urban cities to surveil, raid, and sabotage black political activists, in particular, the Black Panther Party. On December 4, 1969, the Chicago Police Department, working in conjunction with the FBI, carried out a political assassination against Black Panther local party chairman Fred Hampton in his sleep. COINTELPRO ended in 1971, but the Detroit Police continued its practices of spying on black leftist groups that challenged police brutality.

In 1972, DPD's surveillance efforts increased with anti-STRESS sentiment from the public. Informants kept track of all names and numbers at meetings and protests ranging in size from a dozen to 5,000 people in attendence. At many of these meetings, according to DPD's diligent notes, comparisons were made between the Vietnam war and the practices of the STRESS unit. Mentions were made of "defeating" officials like Mayor Gribbs and Wayne County Prosecutor Calahan and even of "taking care of S.T.R.E.S.S." if the city wouldn't.

Such surveillance and record-keeping practices make clear the police department's fear of being held accountable and lack of transparency within the communities they vowed to protect and serve. They also support theories of police keeping tabs on and targetting the radicals that they saw frequently at gatherings like State of Emergency Committee meetings and anti-STRESS protests.

Unlawful Arrests

[LINK COMING TO ARCGIS MAP (Misconduct incidents isolated)]

Not only were politically active Black Detroiters being closely watched at this time, they were also being unlawfully arrested. While demands for police reform gained momentum, DPD countered, often using high arrest rates as evidence for the effectiveness of their new STRESS unit and other policing tactics. In reality, these arrests represented the criminalization of the Black community. Loitering, disorderly conduct, and resisting arrest were among the most common of charges pressed against Detroiters who were being unlawfully arrested.

Many of these arrests were instances of police officers spinning political expression or large gatherings as criminal activity. Some unlawful arrests, though, were the result of misdirected accusations and a lack of investigation on the part of police. One of the most brutal of these instances is known as the UNICOM incident.

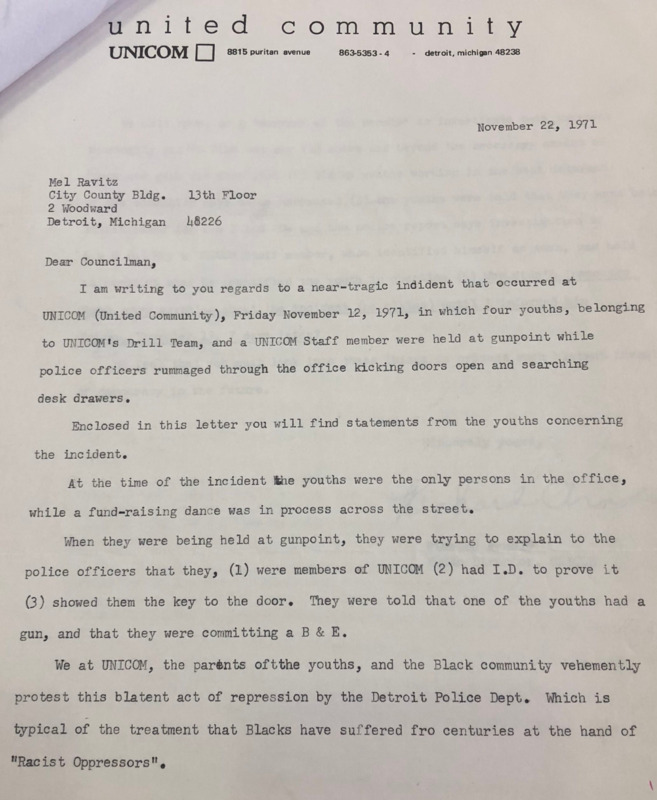

UNICOM, or United Community, was a youth activities center in Detroit. On November 12, 1971, UNICOM became the scene where STRESS officers criminalized the innocuous activities of young African American boys. STRESS officers claimed that they had received a call about a gun on the premises of the United Comminity headquarters, and promptly, twenty police officers arrived at the center--some in uniform, and some in plainclothes. The officers were armed with machine guns, rifles, and shotguns, and knocked on the door of a drill team practice comprised of four boys aged 11-15, and their coach. Two of the children opened the door and were immediately assaulted by officers in plainclothes. While being held at gunpoint, the two boys tried to explain that they belonged to the community center and had reason to be there. Officers mocked the boys, and told them that they were under investigation for breaking and entering into the building.

Despite being told by all of the children and multiple employees of the youth center that the call that was made did not involve them, and that the children and their coach had the right to be there, DPD officers continued to break down doors and hold the children at gunpoint. After some time, officers decided that the call must have been made to a different address and left. However, not before criminalizing the boys and their coach by claiming that they were breaking and entering into a space which they were members. Police also claimed that the boys and their coach had a concealed carry of a weapon, which turned out to be false as well. By comparing the correspondence between Commissioner Nichols and Councilmember Ravitz with the account by UNICOM's Youth Coordinator and accounts of students, it can be noted that the DPD's account attempted to downplay events that occured at the United Community Center in an attempt to publicly lessen their wrongdoings.

“Boys Will Be Boys"

Police brutality was also rampant at this time, not just among STRESS officers, but throughout DPD. Black Detroiters in particular were encountering violence and racism from police. Many were stopped, beaten, yelled at, and even killed by officers on and off-duty. The police department was not outspoken about these issues, and even took measures to cover up especially heinous incidents.

One of the most infamous occurances of police brutality (and DPD cover-up) is known by many as the "Fifth Precinct Incident." On July 22 of 1972, Curtis Lewis, 14, and his brothers found an American flag in a trashcan near their home. There are conflicting accounts on what happened next, but the Lewis’ claim they were playing with the flag, snatching it from one another, when officers approached them, using racial epithets and took the flag away, claiming it was being desecrated. Curtis’ father Gilbert, 34, and uncle James, 28, got involved when they saw the police getting violent. All three were arrested and taken to the fifth precinct, where a shift-change was taking place.

Dozens of DPD officers were moving through the garage when a commotion broke out. Somewhere between 15 and 20 officers began brutally beating James Lewis. An account given in 1973 by a rookie officer who was present then, Officer Jeffrey Patzer, 23, said that the officers were taking turns, holding him up and “kicking the crap out of him. They were beating him with blackjacks, fists, flashlights.”

Two Black officers-the only Black officers present-came forward from the crowd to calm the officers and end the illegal assault, but were also met with brutality from their fellow officers. Patzer said that he could see and even hear one Black officer being beaten in the garage, and that when he asked a sergeant inside if he knew what was going on, the sergeant’s response was, “Boys will be boys.” In the Detroit Free Press, Patzer said, “The beating got down to ‘My turn,’ ‘My turn,’ ‘My turn.’ They were standing the guy up and taking turns smacking him.”

Officers Curtis Burton, 24, and Glenn Walker, 25, filed reports immediately after, and a small article ran on the bottom corner of the Free Press in early August of that year, but no action was taken by DPD. The official police story up until Patzer’s testimony said that a fight had broken out when James Lewis freed himself and kicked an officer in the groin. There was no mention of the beating of Burton or Walker. Because of the testimony he gave in support of Burton’s claims, Patzer was pressured to leave the police force altogether.

Other instances of police corruption and misconduct, like that involving Raymond Peterson planting a weapon on a civilian he had fatally shot, have been documented by a number of organizations and media outlets. Not only has DPD ignored complaints from civilians and black police officers, the department was also involved in more incident cover-ups and even drug activity.

Bring in Jeffrey Patzer in the folder on laptop here

Home invasions and sexual assaults maybe here or in subsection 1?

Sexual Assault--Muriel Roberson Case

add this case, there are additional documents of testimony in Gribbs B 126 F 3, this is also a narcotics corruption case, 17 year old is heroin addict

Violence against women--Muriel Roberson

moved from elsewhere:

The STRESS Unit: Criminals to the Public

Despite the police department's best efforts to publicize low crime rates, over time, STRESS became known for its criminality, not its crime-fighting. Although in its early years only the more radical groups were vehemently against the unit, by mid-late 1972, most progressive groups and African American organizations were calling for it to be abolished.

STRESS engaged in policing practices that most found to be unlawful and racialized, meaning that the undercover unit was baiting, arresting, and killing mostly African American men, and that the officers often failing to identify themselves as police or tell their victims their rights. There was also reasonable suspicion that officers were giving false accounts of these "criminal" incidents, even going so far as to plant weapons or fabricate entire statements.

Officer Raymond Peterson, specifically, became infamous among Black Detroiters who called him “Mr. STRESS” for his involvement in many arrests and shootings carried out by STRESS. He was involved in the shooting of Robert Hoyt, where he was discovered to have planted a weapon on his Hoyt, and the shooting of James Henderson, which sparked suspicion of premeditation on Peterson’s part. Raymond Peterson was a standout, but not the only officer suspected of illegal activity during his time with STRESS.

"The Blue Curtain"

Isaiah (Ike) McKinnon, an African American officer who joined the DPD in 1965, ran up against the so-called "Blue Curtain" of police silence and cover-ups of brutality by fellow officers many times during his career. In 1972, McKinnon was a sergeant in the 10th precinct when he intervened to stop fellow police officers from beating and kicking three African American teenagers after a chase. After he stopped the white officers, he went back to the station house and had the following exchange with the lieutenant on duty:

- McKinnon: "A number of officers were savagely beating three young men on the street and I stopped it."

- Lieutenant: "What are you going to put in your report?"

- McKinnon: "Exactly what I saw."

- Lieutenant: "Ike, if you do that you're going to cause these guys to lose their jobs."

In the video excerpt below, Ike McKinnon describes this incident and the repeated efforts by the DPD hierarchy to convince him to drop the matter, revealing the "Blue Curtain." He also recites the law enforcement code of ethics that police officers are supposed to "respect the constitutional rights of all," which he believed and tried to follow, while many in the DPD did not.

Sources:

Detroit Free Press, April 9, 1973

Detroit Free Press, July 31, 1975

Roman S. Gribbs Mayoral Collection, Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library

Mel Ravitz Papers, Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University

Detroit Free Press, August 5, 1972

Elizabeth Hinton, From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime: The Making of Mass Incarceration in America (2015)

Isaiah McKinnon, Stand Tall (2001)

Isaiah (Ike) McKinnon Interview, Part 1, December 3, 2019, https://lsa-dss.mivideo.it.umich.edu/media/t/1_rxtil0md/145739741