"We are providing resources for a squirmish, not those needed to win a war" -Charles Rangel, 1986

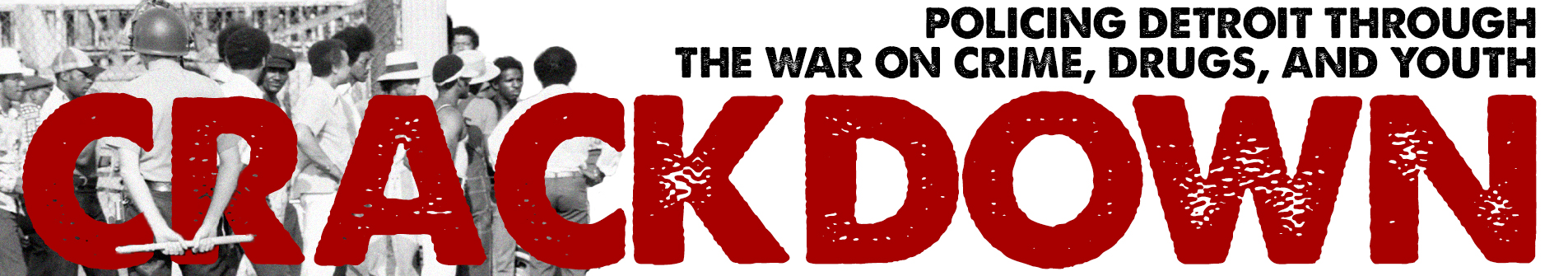

American War on Drugs

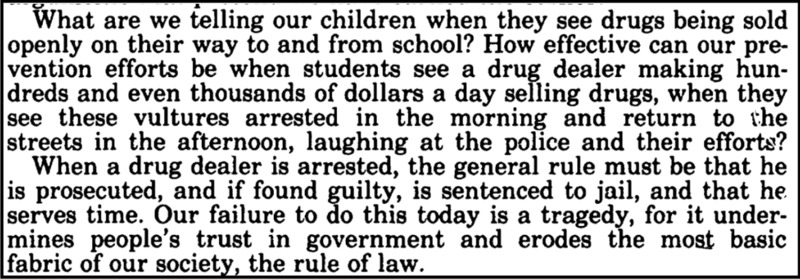

While the War on Drugs was well underway by 1986, the late '80s saw some major shifts in how policies were focused. While the previous focus was the use and dangers of heroin, cocaine took center stage in the turn of the decade- alongside the growing fear of the rise in marijuana use among American youth. This especially had a role in influencing early strategies that put heavy emphasis on prevention and education programs. In the months leading to the passing of the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986, much of the congressional argument stressed the belief that the federal government wasn't doing enough to prevent school-aged kids from being dealt drugs. At a hearing before the Select Committee on Narcotics Abuse and Control in July of 1986, Senator D'Amato from New York spoke specifically to this issue, stressing the need to send a message to dealers and users that their actions have consequences.

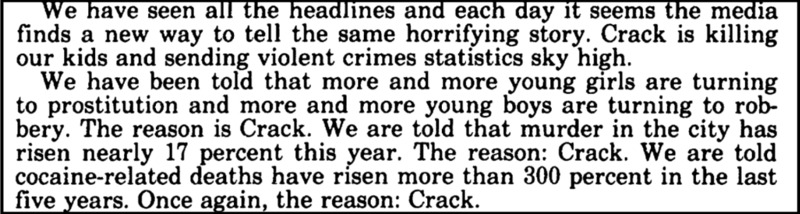

Additionally, at this committee the dialogue moved towards a more emotional call to action, essentially blaming all of the perceived ills of society on crack cocaine. Specifically, New York Congressman Mario Biaggi largely conflated rising crime rates with the use of crack. Similar beliefs were shared in Michigan, which were expressed by Inspector Joel Gilliam of the Detroit Police Department's narcotics division. He submitted "A Report From the Frontlines" to the House Select Committee on Narcotics Abuse and Control detailing the scope of the crack cocaine crisis in southeastern Michigan. Gilliam states that before 1985 the DPD had never heard of crack cocaine, but that it quickly became a catalyst for rising crime rates and intensified the fear of crime in neighborhoods. He claimed that youth crime "is a direct result of the crack crisis" and that this was a national issue that would require "nothing less than a total commitment from all segments of society"

The Select Committee on Narcotics Abuse and Control held a further hearing in the weeks leading up to the passing of the 1986 act, with the Congressional Black Caucus leader Charles Rangel at the forefront of the debate. Rangel, an African American from Harlem, served as a strong advocate specifically for the need for further funding for all drug-fighting endeavors and attributed the drug crisis to "inadequate policies, insufficient resources, and a lack of commitment to confronting the problem." Discrepancies between the Senate and House versions of the anti-drug legislation rested on the issue of funding, with Rangel stressing that the government should focus less on the immediate costs and "provide what is needed to win the war" in order to see long term effects. This issue of funding and how it would be allocated across different programs was one of the main areas of argument- specifically in regards to rehabilitation versus law enforcement. Democratic members of congress largely vocalized the need to put a primary emphasis on educational resources and treatment programs, while conservatives tended to argue for using the bulk of funds for policing and more punitive efforts. This difference in political opinion on where federal funds should be distributed is highlighted below in a discussion with Bill Butinski, the executive director of the National Association of State Alcohol and Drug Abuse Directors and Edward Jurith, the Director of the Office of National Drug Control Policy. Despite this argument, the urgency for a more comprehensive drug bill in America crossed party lines.

Discussing The Issue of Funding Allocation

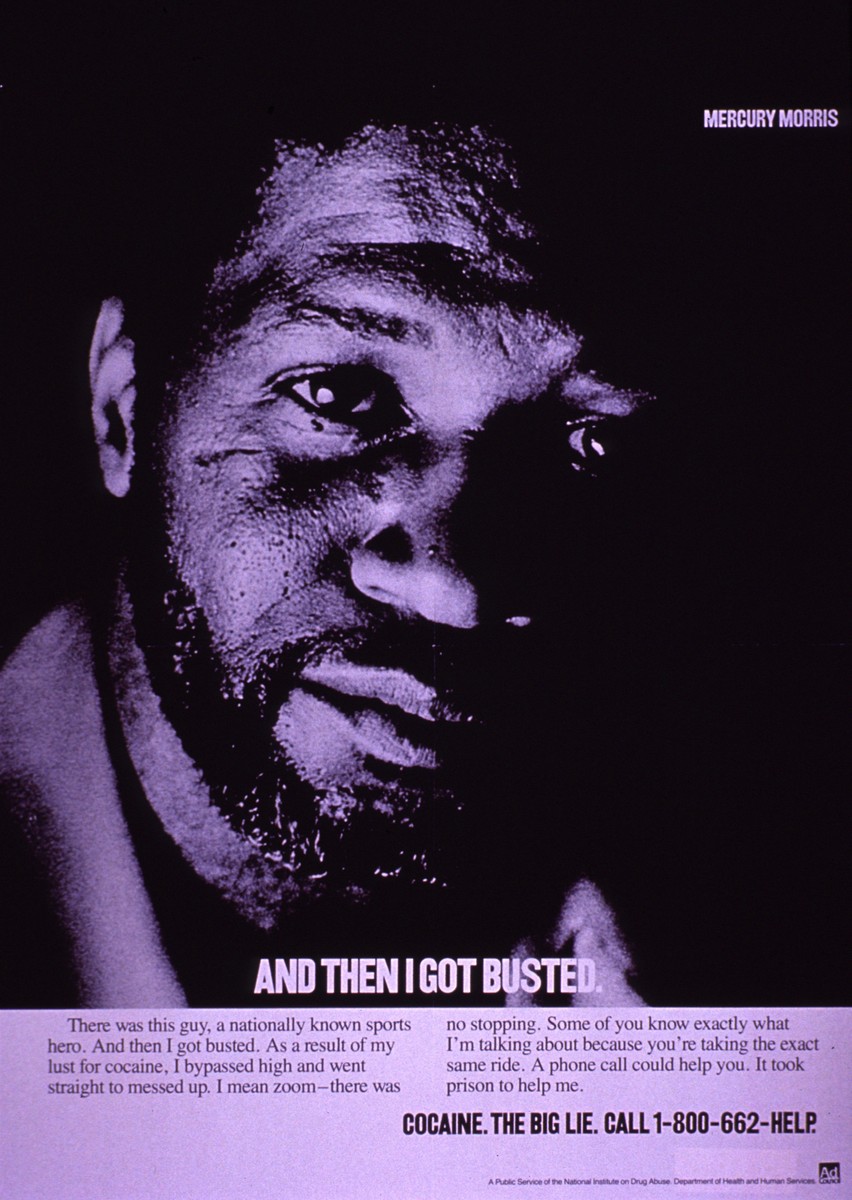

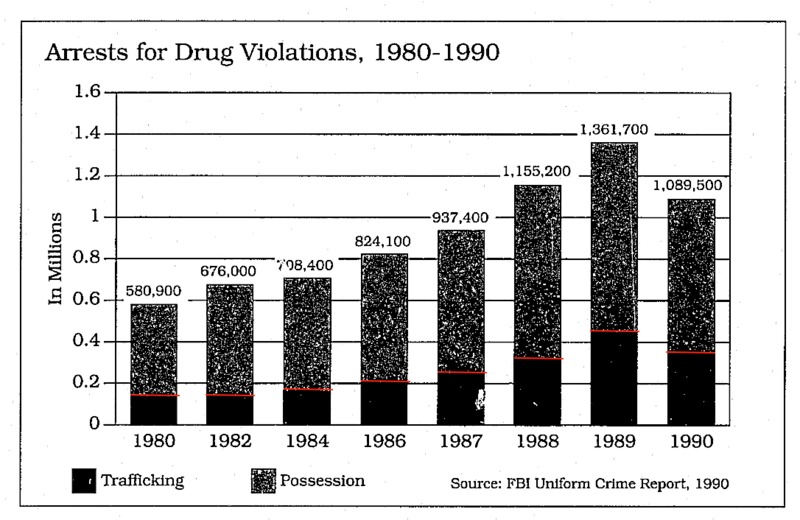

The Reagan administration's 1984 anti-drug strategy and the 1986 Anti-Drug Abuse Act took a more comprehensive approach that focused heavily on prevention programs, dealing with international interdiction efforts, and theoretically tackling large scale drug trafficking through minimum sentencing laws. In reality, low level offenders caught with possession or local distribution were those most often arrested and affected by sentencing minimums, as law enforcement focused the majority of their efforts on inner cities like Detroit. Into the later 1980s and early 1990s, the strategy became more explicitly centered around cracking down on these small-scale street dealers-based on the belief that it would bring about a large disruption on the entire network of drug trafficking by deterring people from getting involved in dealing and using. However, as arrests for drug-related offenses continually increased through the 1980s, it actually resulted in the rate of arrests for possession to increase at a much higher rate than traffickers. This paralleled the gross increase in aggressive police tactics brought about by the reliance on tactical teams to perform drug raids. With the scope of asset forfeiture broadened by the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986, it became incentivized to take a more militarized approach to law enforcement. This led to the frequency of raids and use of tactical squads to increase greatly, specifically in Detroit through the formation of Operation Crack Crime. While Congress played a large role in the passing of anti-drug legislation, presidents, governors, and local mayors enacted their influence and were important contributors to the heightened fear of crime and drugs. The War on Drugs as a whole functioned as a sort of feedback loop, where constituents would demand more of their representatives, who would then guide federal policy and presidential attitudes, which would filter back down to smaller forms of government and local policies. This function overall led to a strengthening of the mass panic surrounding the largely perceived "epidemic" of drugs.

Sources:

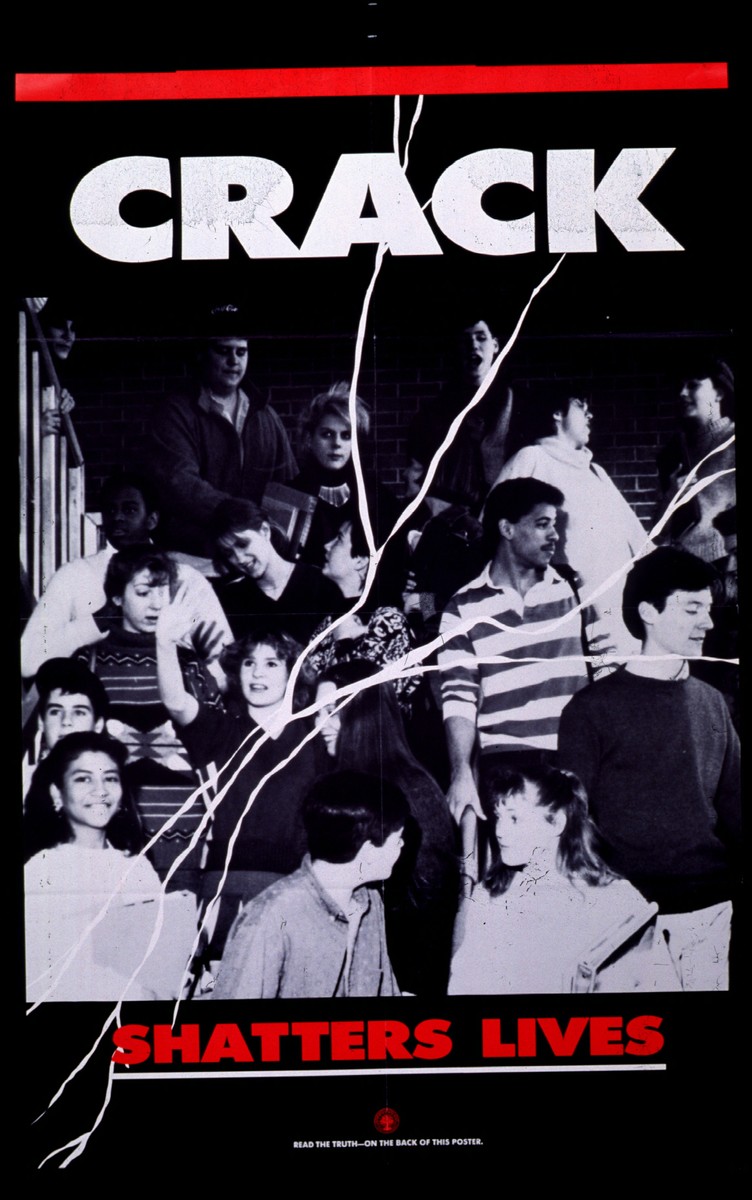

United States Dept. of Education. Crack Shatters Lives. Washington, District of Columbia, 1989. From the United States National Library of Medicine, http://resource.nlm.nih.gov/101452472.

U.S. Congress, House of Representatives, Select Committee on Narcotics Abuse and Control, Testimony of Senator Alfonse D’Amato (D-New York) in “Trafficking and Abuse of Crack in New York City”, 99th Cong., 2d sess., July 18, 1986, 3-4.

U.S. Congress, House of Representatives, Select Committee on Narcotics Abuse and Control, Testimony of Representative Mario Biaggi (D-New York) in “Trafficking and Abuse of Crack in New York City”, 99th Cong., 2d sess., July 18, 1986, 8-11.

U.S. Congress, House of Representatives, Joint Hearing before the Select Committee on Narcotics Abuse and Control and the Select Committee on Children, Youth, and Families, Report by Inspector Joel Gilliam of the Detroit Police Department in “The Crack Cocaine Crisis”, 99th Cong., 2d sess., July 15, 1986, 169-178.

Representative Charles Rangel (D-Harlem), “Opening Statement to Annual Meeting of the Congressional Black Caucus,” Select Committee on Narcotics Abuse and Control Hearing, “The Federal War on Drugs: Past, Present, and Future,” October 3, 1986, 53-64.

“National Drug Control Strategy: A Nation’s Response to the Drug Crisis,” United States Department of Justice, Office of National Drug Control Policy, January, 1992, 1-116.

1984 National Strategy For Prevention of Drug Abuse And Drug Trafficking, United States Department of Justice, District of Columbia, United States, September 10, 1989.

National Drug Control Strategy of 1989, District of Columbia, United States, September 15, 1989

Indexed Legislative History of the Anti-Drug Abuse Act 1986, United States Department of Justice, 1986