Reagan's National Drug Strategy

"What an insult it will be to what we are and whence we came if we do not rise up together in defiance against this cancer of drugs." - Ronald Reagan

The Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986

In September of 1986, President Ronald Reagan alongside his wife Nancy spoke to the nation in regard to their combined support to create strategies and policies that would work to combat the growing issue of drug abuse in America. As Nancy promised to continue to spread awareness of the dangers of drugs to American youth through campaigns such as “Just Say No” the president informs of his new proposals that will work to combat the “epidemic” of drug use and create a safer nation. This legislation, the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986 became law a month later- increasing penalties for drug possession, creating minimum sentences for drug-related offenses, increasing funds for drug enforcement measures, and importantly resulted in the creation of a disparity of 100:1 for crimes related to crack versus powdered cocaine.

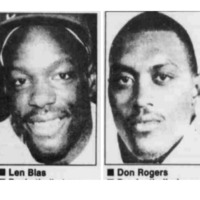

In June of 1986, two widely known athletes in the United States died in less than two weeks of each other, both as a result of cocaine overdoses. The tragic deaths of Cleveland Browns football player Don Rogers and the University of Maryland basketball star Len Bias, two talented young men in their prime, sparked a media uproar that government action needed to happen immediately to prevent more unnecessary destruction. This led to the expedition of the passing of the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986, legislation that would gain a legacy of controversy.

Crack cocaine, given that it is much cheaper to produce, was utilized more heavily in areas of low socioeconomic status, consisting primarily of minority groups. Powdered cocaine was significantly more expensive, and therefore used by predominantly upper-class white Americans- individuals that were far less likely to be policed in the forefront and further improbable to receive harsh punishment if they were charged with a drug-related crime. The 1986 bill created minimum sentencing laws with a 100:1 disparity between powder and crack cocaine, supported by untrue claims that crack is more dangerous and addictive, while there is pharmacologically no difference in effects between the two forms. Possession of 5 grams of crack (approximately 0.18 oz) would lead to a 5-year minimum sentence, and 50 grams (approximately 1.8 oz) would elicit a 10-year minimum sentence; an individual possessing powdered cocaine would have to have 100 times as much to trigger the same penalty. These were justified through the assertion that mandatory minimums would greatly reduce the number of large-scale drug traffickers, but in reality, most often affected users and street dealers. This disparity overall led to a major racial and class imbalance where minorities faced exorbitantly harsher punishment for use and sale of virtually the same drug as their affluent, white counterparts. The extreme actions taken against crack specifically alongside the continued media hype of the dangers of the drug led to the major focus of public attention and militarized police efforts to be on the inner cities, which had naturally formed a market around the profitable drug. Meanwhile, suburban and upper-class users of powdered cocaine were largely ignored in policy, media portrayals, and enforcement measures.

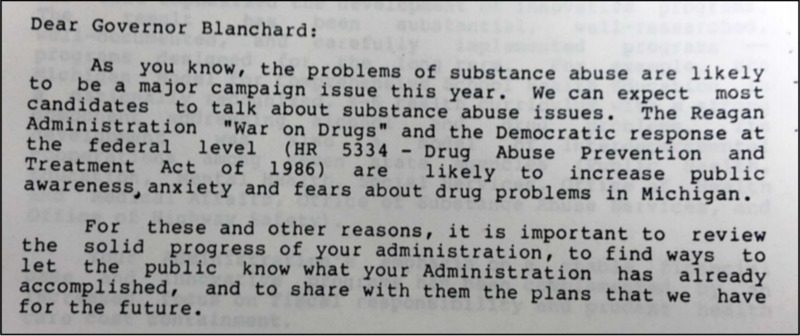

An additional aspect of the Anti-Drug Abuse Act was that it made the forfeiture of property much easier by law, specifically allowing for the seizure of belongings equating to the value of illegal goods if those substances were no longer available. Consequently, state legislatures similarly expanded their search and seizure policies in congruence with increased law enforcement efforts. This is just one example of how Reagan’s policies did not unilaterally affect federal regulations but were further influential in shaping state and local strategies. In Michigan, almost immediately after Reagan announced his national initiatives, state departments with ties to public health and narcotics were urging the initiation of comprehensive tactics to begin the attack on drugs at the state level.

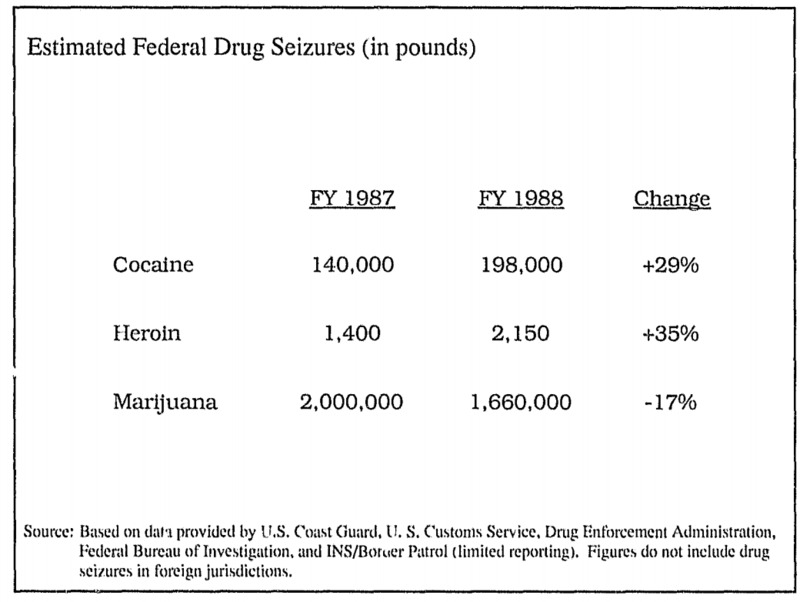

The 1986 act was just the beginning- the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1988 was signed two years later which furthered many of these measures, and actions continued into the early 1990s. It is evident that well through the late eighties, crack specifically continues to be considered the more serious and problem-causing drug, and a main reason to amp up the national war. As funding for drug-fighting programs increased, there was a trend towards using this money for increased policing and expansion of the criminal justice system, as opposed to efforts for rehabilitation.

"Just Say No"

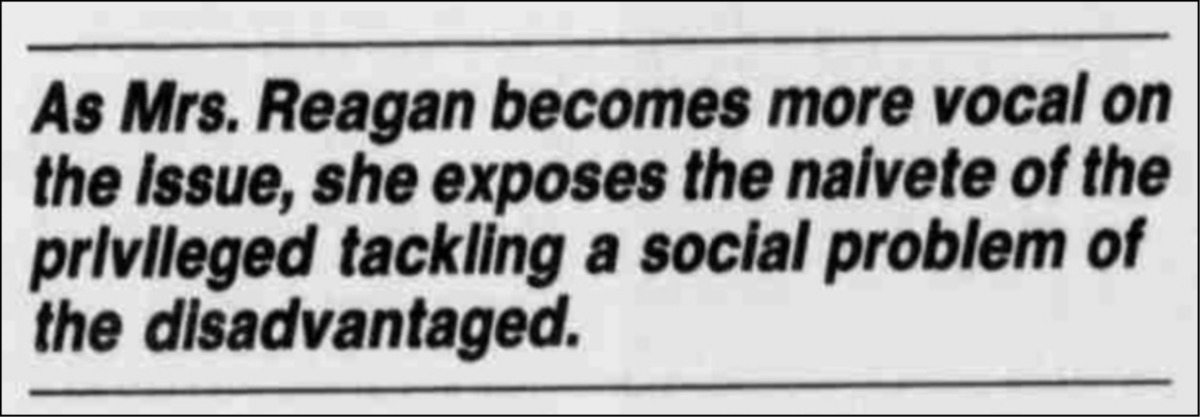

“‘Just Say No’ sounds just fine as the advice given to privileged youngsters who are offered candy by strangers. But when the First Lady suggests the phrase as a final solution to youthful drug abuse, it smacks of a gross ignorance of street addiction, peer pressure, and the agony that drives poor children, especially, to the bottle, the needle, and the pipe.” -Les Payne, Detroit Free Press, 1986

While the deaths of famous figures may have been an important spark in hastening public outrage, Nancy Reagan had been influencing perceptions of the gravity of drug use from the early 1980s through her “Just Say No” movement- a campaign that would define her time as first lady, but would also be criticized for its obtuse nature and overall ineffectiveness. Nancy traveled around the country to schools, rehabilitation centers, and anti-drug rallies as well as appearing on television and radio to spread the message that drug abuse could be largely averted by simply refuse the proposition of trying drugs. “Just Say No” clubs were implemented in schools and communities nation-wide, with kids encouraged to pledge that they would resist the pressures and temptations of drug use. Overall, this strategy grossly simplified the solution to decreasing adolescent drug use and was shown to be a largely ineffective form of preventative education. It was further criticized in terms of ignoring the real systemic causes of drug use in lower-class areas where the issue was most prevalent.

The issues of drug use and abuse would soon become major points in election campaigns across all levels of government, with a bipartisan acknowledgment of a need for stricter laws and increased enforcement. In the national as well as state and local spheres, departments and agencies such as the DEA began to increasingly release reports detailing continuing drug threats, actions being taken, and statistics showing how these new regulations and efforts were being implemented. While drug-related initiatives were increasing incredibly throughout the late 1980s, fears of the corruption of youth through illicit substances and of general national crisis grew in parallel.

Sources:

“President Reagan's Address to the Nation on the Campaign Against Drug Abuse” September 14, 1986. Reaganfoundation.org

Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986, Public Law No: 99-570. U.S. Statutes at Large

3207. https://www.congress.gov/bill/99th-congress/house-bill/5484/all-info

Vagins, Deborah., Jesselyn McCurdy. “Cracks in the System: Twenty Years of the Unjust Federal Crack Cocaine Law,” American Civil Liberties Union (2006). https://www.aclu.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/drugpolicy/cracksinsystem_20061025.pdf

“Just Say No,” History. August 21, 2018. https://www.history.com/topics/1980s/just-say-no