Forfeiture Scandals

“Asset forfeiture is a powerful tool used by law enforcement agencies, including the FBI, against criminals and criminal organizations to deprive them of their ill-gotten gains through seizure of these assets.” — FBI.gov

Video Explanation: Civil Asset Forfeiture

Asset forfeiture is a long-debated but longer-used system of claiming or reclaiming the physical assets of convicted, charged, or even suspected criminals and the usage of these assets for the fiscal gain of the law enforcement agency that seized them. Asset seizure may occur with cash, objects of value, drug seizures, and sometimes the cars or houses of those charged with criminal acts. In the Detroit Police Department in the mid- to late-1980s, asset forfeiture was utilized heavily as a way to bolster the funding of an individual precinct or the greater Detroit Police Department. Since the 1980s were wrought with police crackdowns on drug enforcement, and additionally the DPD became accustomed to regular and violent drug raids, one of the most common forms of asset forfeiture used during this time was the seizure of narcotics from crack houses or supposed drug dealers.

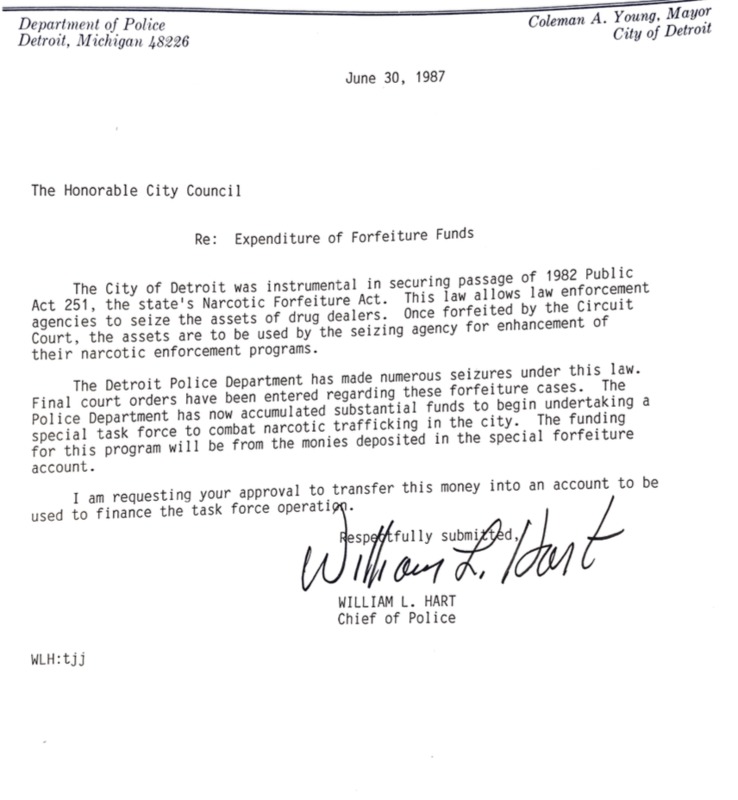

The DPD’s forfeiture of narcotics became not only a regular practice, but also one worthy of intra-departmental investigation and later state-wide suspicion. This comes from a trend within the department of failing to follow the procedure for seized or forfeited assets to the DPD of logging the quantity, type, class, and the worth of any particular seized drug. Michigan state law was amended in 1982 -- with the advocacy of Police Chief William Hart -- to account for narcotics within the types of goods that DPD officers could seize during the adjudicative or arrest process of a given person. Hart was notably supportive of this legislation, given that it allowed more freedom to his officers to seize and liquidate assets from narcotics dealers.

The DPD developed a forfeiture department to deal with the influx of assets being seized in drug raids as well as street policing incidents. Forfeiture departments work interdepartmentally to distribute funding based on the profits made from asset seizure. The DPD was becoming a profitable institution as it pulled funds from suspects and criminally charged persons.

From Section 1(a) of the Public Act 368, Forfeiture Proceedings:

"The local unit of government that seized the property or, if the property was seized by this state, the state shall notify the owner of the property that the property has been seized and, if charges have been filed against a person for a crime, the person charged, and that the local unit of government or, if applicable, the state intends to forfeit and dispose of the property by delivering a written notice to the owner of the property or by sending the notice to the owner by certified mail. If the name and address of the owner are not reasonably ascertainable, or delivery of the notice cannot be reasonably accomplished, the notice must be published on the local unit of government's or the department of the attorney general's public website and in a newspaper of general circulation in the county in which the property was seized, for 10 successive publishing days." -- legislature.michigan.gov

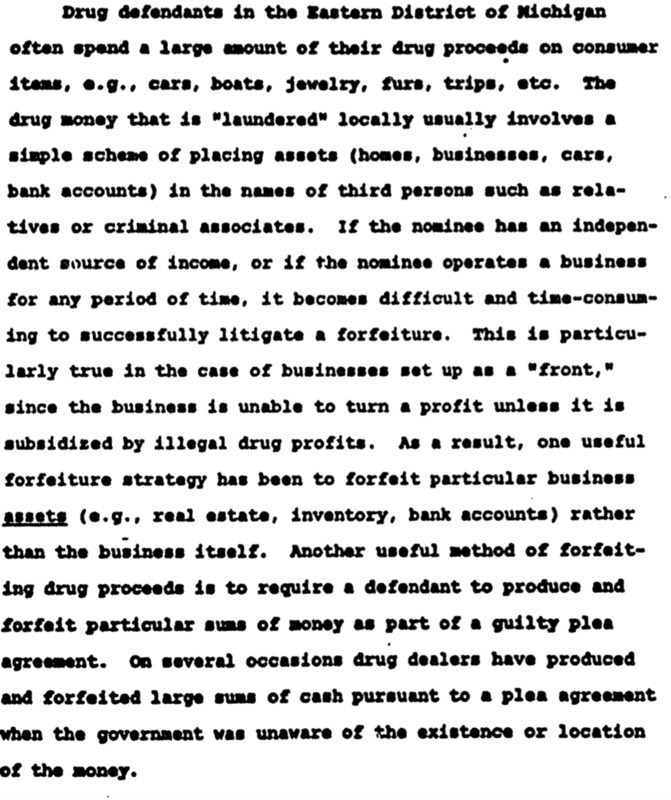

An interesting component of asset forfeiture is that while in narcotics cases the item seized is the item implicating the person in a crime, other times the assets seized exist completely independently of the charges. For example, the seizure of houses and cars from suspected and charged drug dealers may have sometimes been subsidized by drug money, but they themselves are not a part of the arrest or the evidence used to arrest the person for dealing drugs. This was an intentional amendment to the 1978 Michigan Public Act 368, which dictates the procedure for assets forfeited to the police.

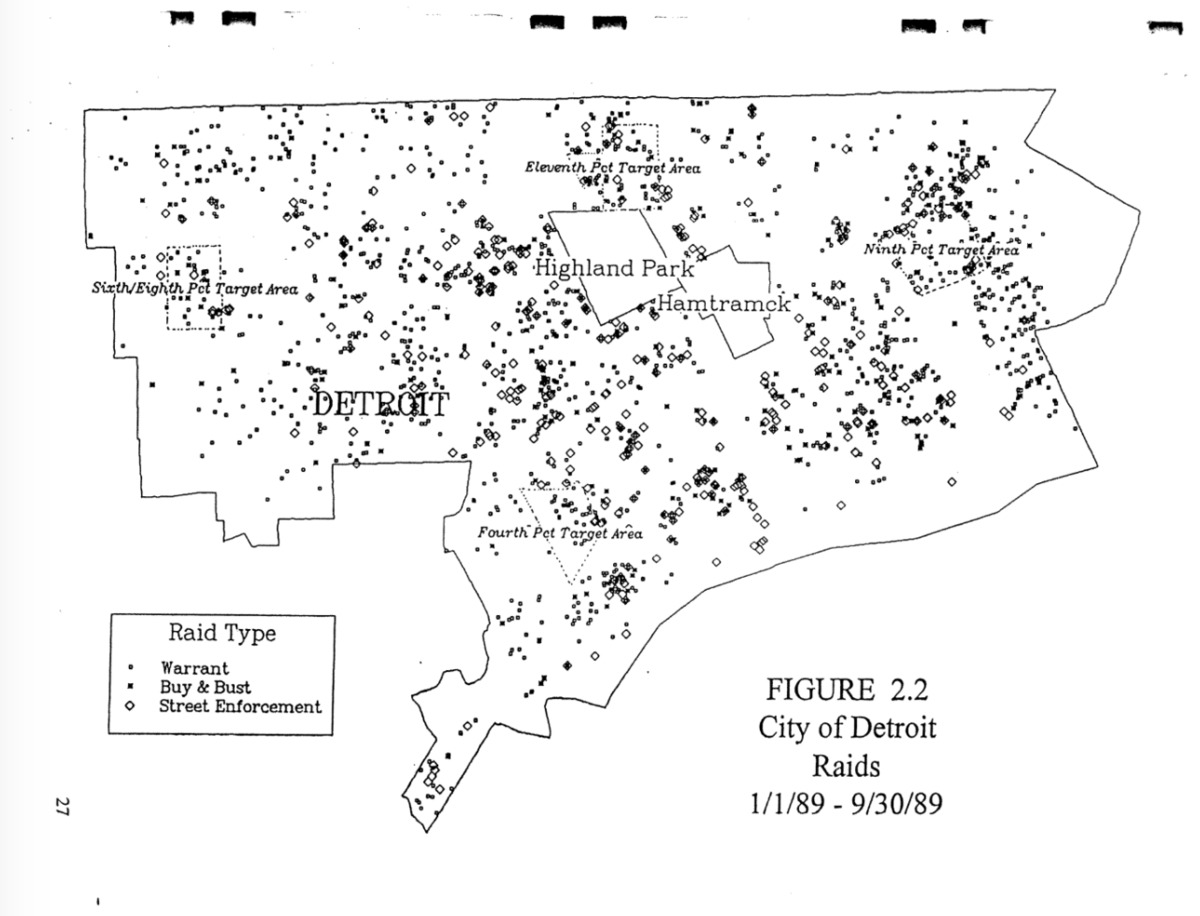

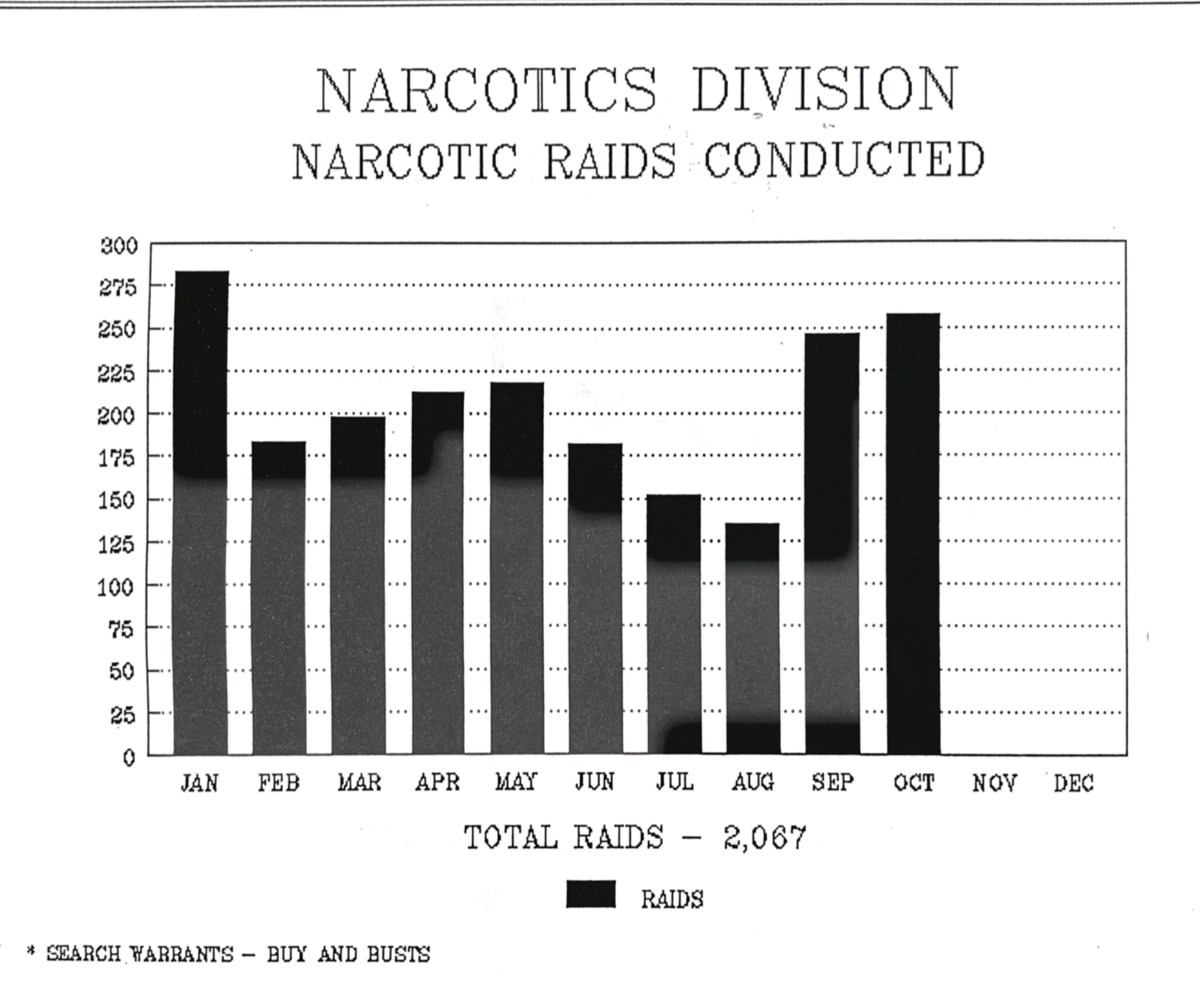

Asset forfeiture and the federal War on Drugs interacted in a simbiosis during the 1980s; the push to get drugs like crack and even marijuana off the streets of major cities became a major facet of individual cities' drug task force plans and law enforcement planning. Because of this, the number of raids went up, and with it, the number of assets seized -- which were then liquidated and processed as funding for the police department. The cycle of narcotics asset forfeiture and narcotics raids became entirely self-sustaining and a testament to the economics of the War on Drugs. Individual precincts (and on a larger scale, entire police departments) had an direct economic incentivization to raid buildings and communities suspected of harboring drug dealers.

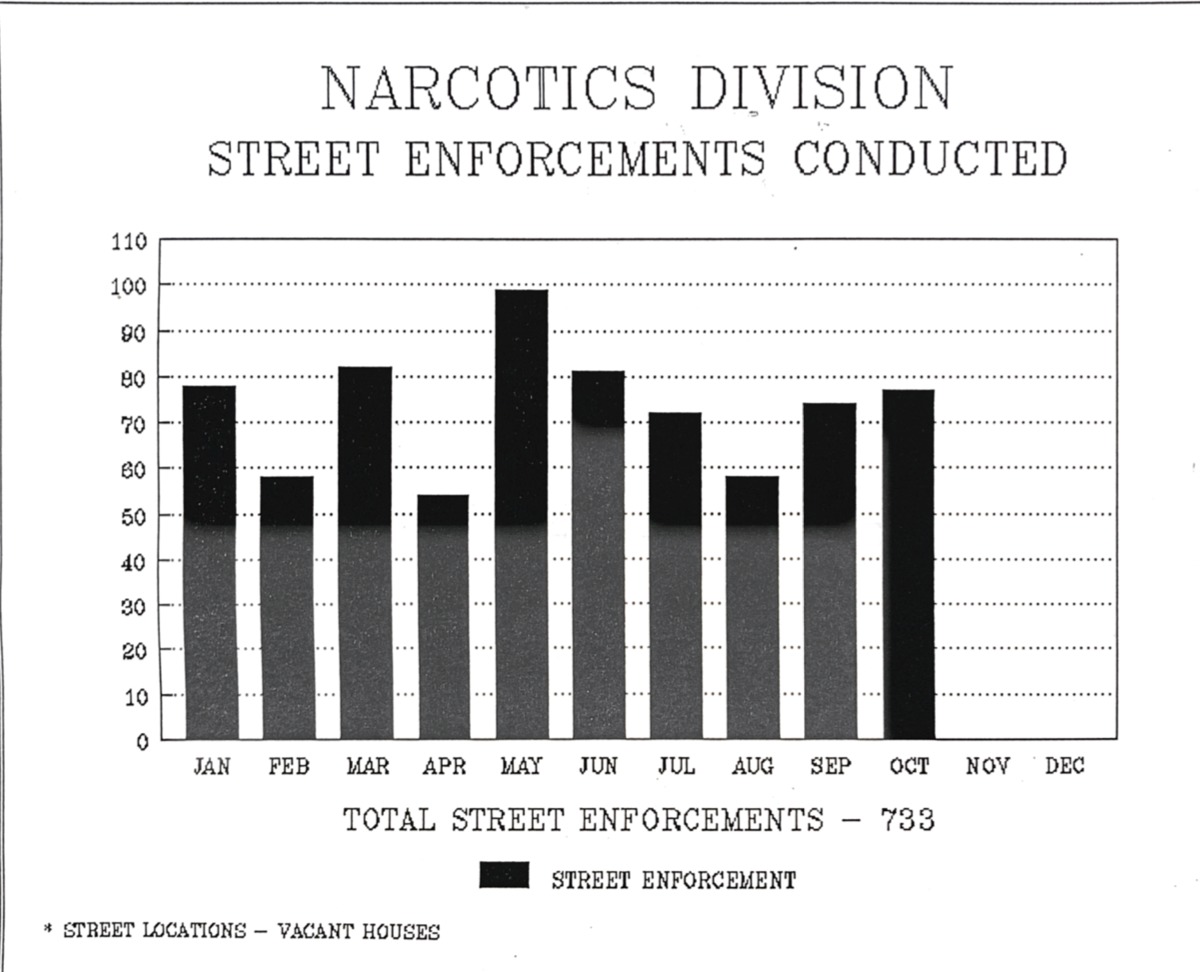

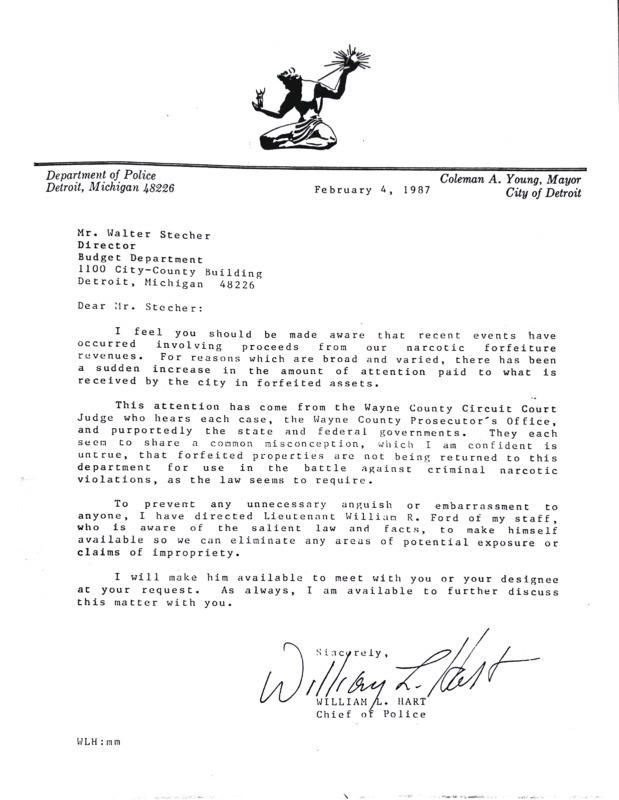

The DPD went under investigation in the late 1980s for misuse of assets seized by officers in drug-related raids and arrests. Narcotics seizures heightened from 1986 to 1989 following statewide conference on drug strategy following the 1988 amendments to the Anti Drug Abuse Act of 1986 and the DPD’s initiatives to increase raid-based arrest in lieu of street enforcement arrests. DPD Chief Hart communicated with multiple city administrators and government officials to both investigate and silence the suspicion of misuse of funds and items seized in drug raids. The missing or misused funding from the raids was classified as a miscommunication on the part of the officers -- Hart described them as not knowing what procedure to follow or logistics to observe when cataloguing seized assets from raids and arrests.

1988 Release to City Council on Asset Seizures and Funding, January - October

In 1988, between the months of January through October alone, there were 2,067 drug raids which amassed over $3 million in forfeited assets.

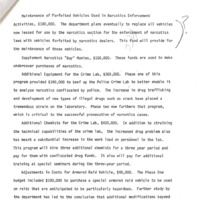

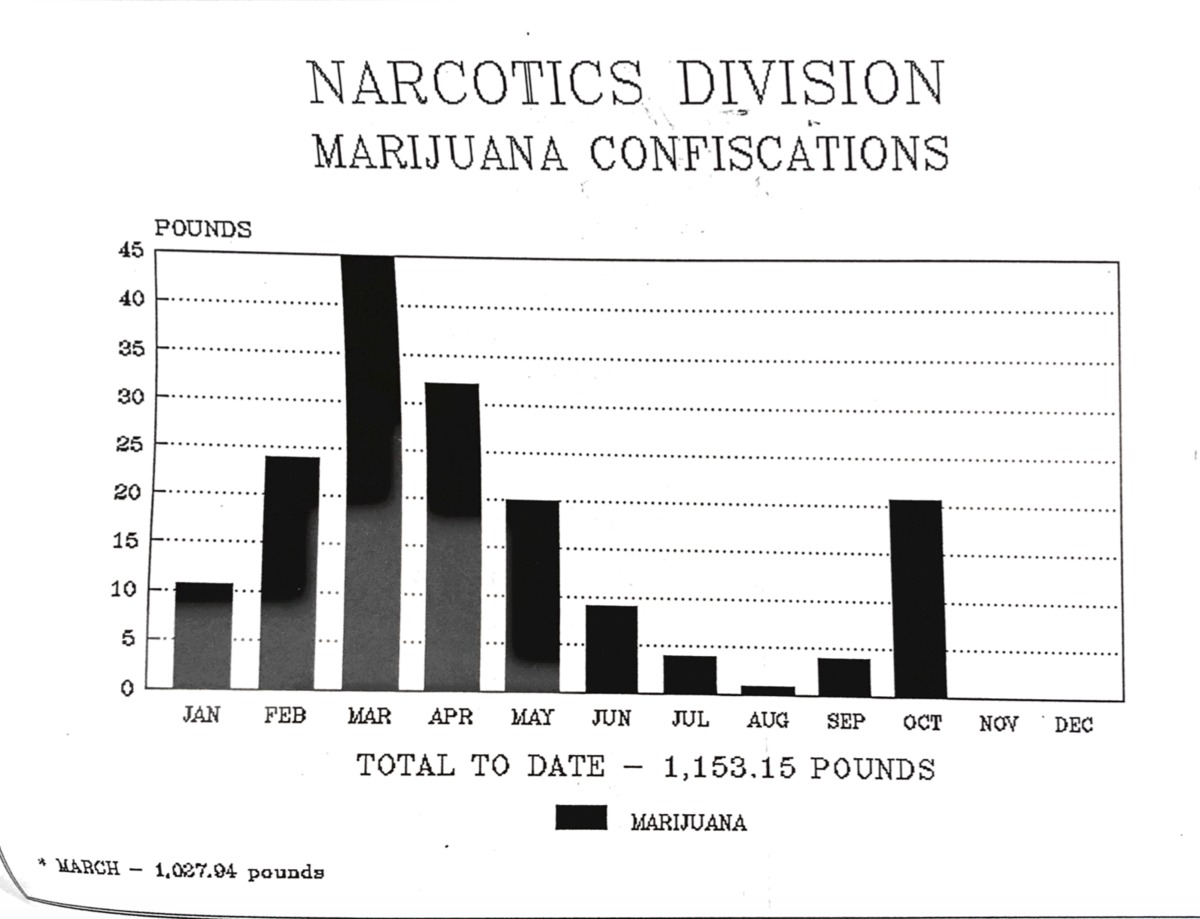

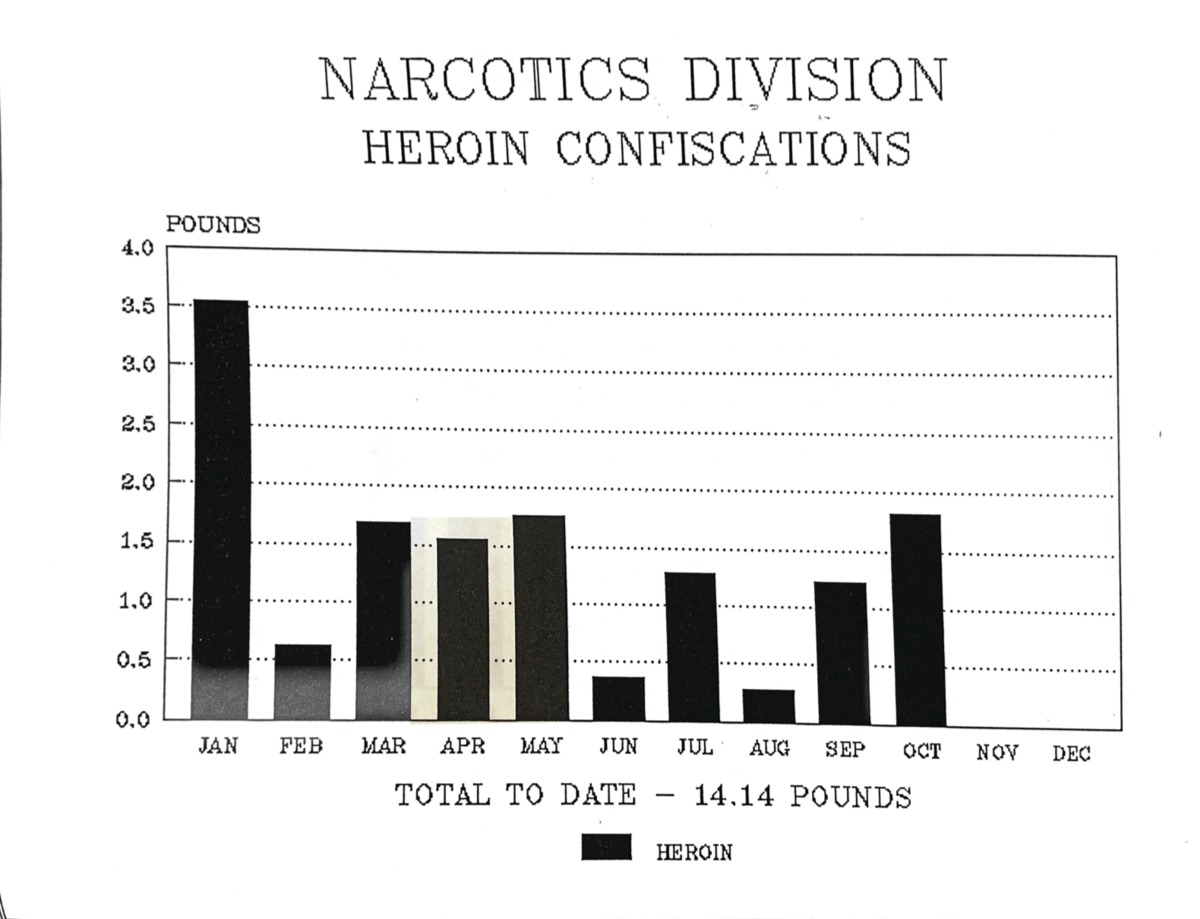

Statistics on Drugs Confiscated in January - October 1988

Sources:

Minutes of the Board of Police Commissioners, 1987-88. Burton Historical Library and Archive.

Folder 19 Box 262, Coleman A. Young Papers. Burton Historical Library and Archive.

Folder 3 Box 54, Mel Ravitz Papers. Reuther Historical Archive at Wayne State University.

Asset Forfeiture Laws: the State of Michigan. legislaiture.michigan.gov