Drugs in Detroit

The correspondence between Detroit Police Chief William Hart and Detroit Mayor Coleman A. Young is an insightful look at Young's policies and relationships with the DPD. As the police department cracked down on narcotics with increased funding and manpower for raids, drug busts, and various multi-person "Operations," Mayor Young's rhetorical support for both the Federal and State level War on Drugs was a vital public statement to Detroit residents. Mayor Young was tasked with mediating between the state's funding choices for implementing the War on Drugs and Detroit's dire need for some capital relief in its effort to sweep crack cocaine from the streets.

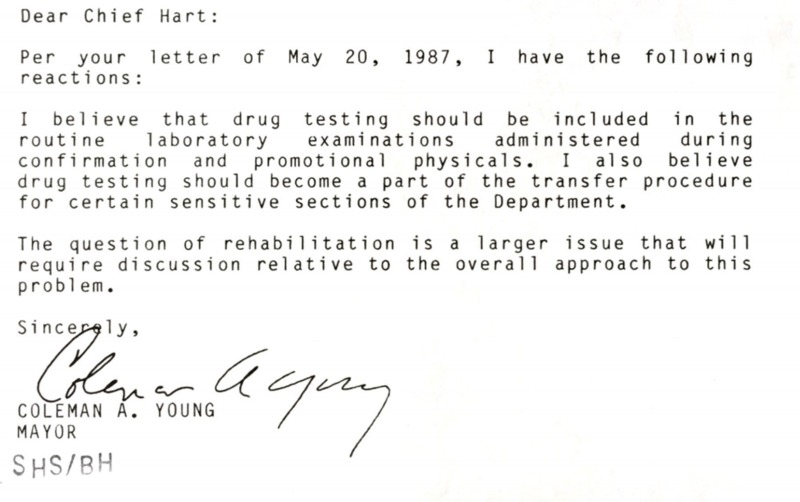

Even more vital between Chief Hart and Mayor Young is the discussion of various officers dismissed for drug abuses, and how they should be dealt with in such an "anti-drug" era as this one. Inter-precinct transfers and paid suspensions were the norm and the standard for non-violent (and often even for violent) offenders within the department.

Continued communication between Detroit Police Chief William Hart and Mayor Coleman A. Young exhibits both that there was some degree of growing interdepartmental concern about police drug corruption, as well as the intentional framing of the issue as “a few bad apples.” Mandatory drug testing as early as 1987, when trials for DPD drug corruption would happen over two years later, is a telling addition to the DPD corruption timeline. Additionally, the intervention of the mayor's office into the police department's conduct is a recurring theme throughout this time period; with Operation Crack Crime, the investigations against narcotics asset forfeiture, and later, the lawsuits against officers for major crack-related misconduct.

The DPD went through tumultuous legal disputes throughout the late 1980s in regard to officers' drug usage. During this time, the mayor's office proposed and drafted a Drug Testing Policy which would mandate testing for not only uniformed officers, but civilian administrators in the police department as well. This proposal sought to appease the DPOA, who had been outspoken critics of testing officers for drug usage, as well as respond to public outcry about growing drug-related police misconduct. Drug screening is framed not only as a regional solution to the DPD's drug problems, but also an issue with which the city could ground itself in the constitution. The Law Department of Coleman Young's administration actively sought to sidestep any ongoing legal disputes with this policy, whether that be from the public or from the officers themselves. With such a powerful union, oftentimes police-related reform was stagnated not in the political processes, but at the foot of the DPOA.

Drug tests proved successful in multiple precincts, but the police officer's union took issue with the random nature of the testing, and later litigated against the procedure.

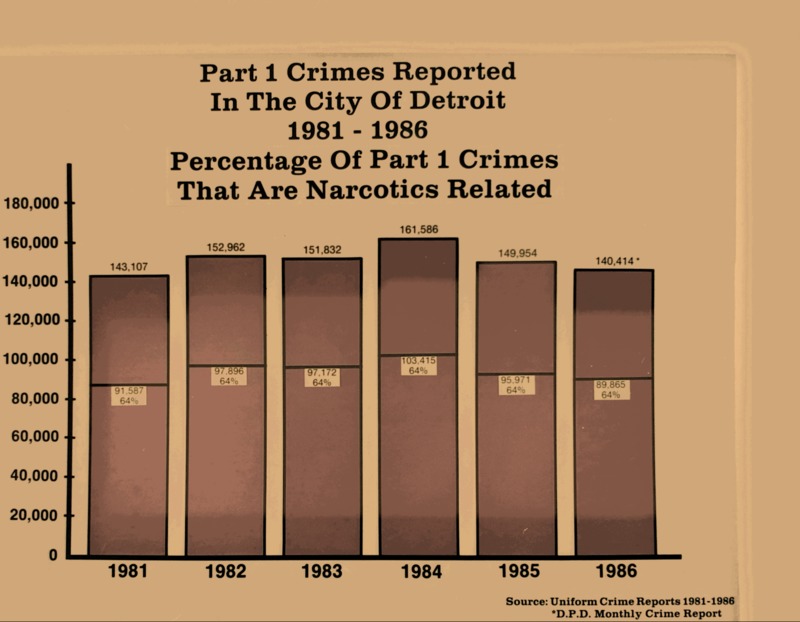

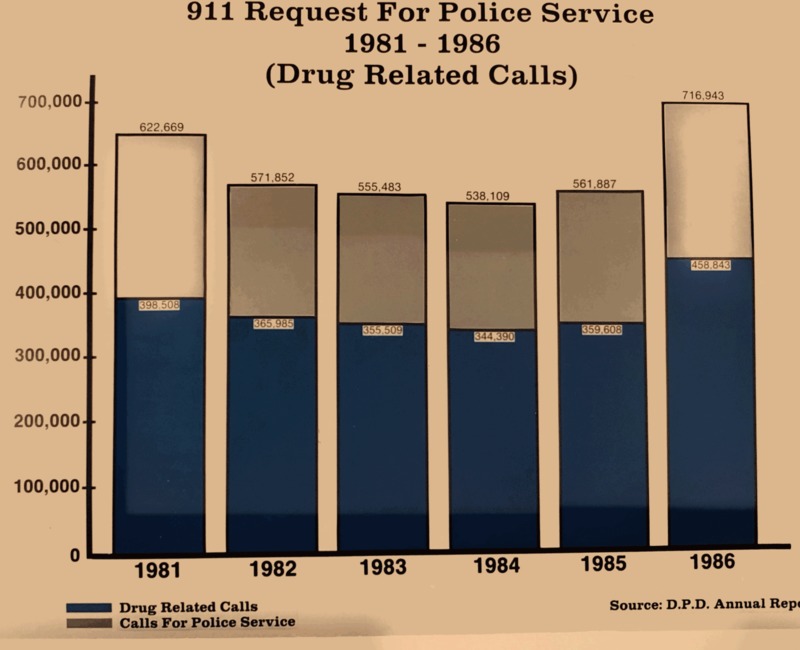

Detroit’s place in the national and state level Wars on Drugs was as an epicenter of crack crime and a major focal point in policing and law enforcement tactics. The DPD under Coleman Young were recipients of notable grants and financial investment, but even with this, the city seemed to be struggling to accommodate the financial burden of implementing a city-wide War on Crack.

While Michigan's Criminal Justice System certainly received funding from the 1986 Anti Drug-Abuse Act, the funding was proportioned throughout the different counties in the state and Young's administration was at times openly critical of the amount that the city of Detroit received. Detroit, being the major metropolitan population center in the state, was burdened with the identity which many cities carry; it is separated from smaller towns and suburbs based on the racial and economic demography of its residents. This became apparent in the War on Drugs as Detroit's post-ADA funding went primarily toward punitive drug policing, whereas in primarily white, higher-income neighborhoods, the emphasis in programatic funding was drug education and the Reagen-era "Just Say No" theory.

The Anti-Drug Abuse Act came at a key time in the social climate of Detroit's drug markets. With the police arresting and disbanding Young Boys, Incorporated just years prior, the city had a power vacuum in terms of drug sales and vice-market employment for young Black youth in the inner city with no other options. This, along with the introduction of crack cocaine into the city in addition to marijuana, brought drug use to be the immediate and pressing topic of both legislation and citizen panic.