Hart’s Conviction

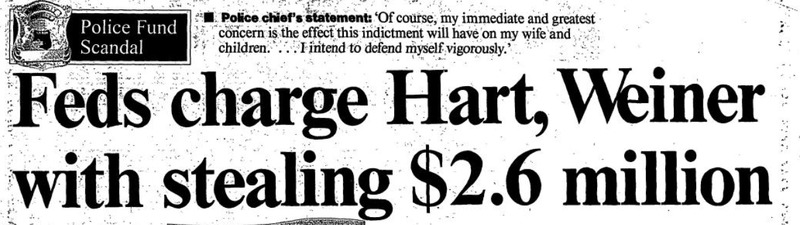

In early 1991, a federal grand jury released criminal indictments against Chief William Hart and one of his former deputies, accusing them of embezzling millions of dollars from the city and marking the culmination of one of the highest-reaching scandals in the history of the Detroit Police Department (DPD). For more than a year prior, federal investigators had been looking into the finances of Chief William Hart. They found evidence that Hart and his former Deputy Chief, a man named Kenneth Weiner, together stole $2.6 million from the DPD “Secret Service Fund.” Immediately following his indictment Hart was forced to step down as Chief of Police. In 1992 he was finally convicted of embezzlement and received a notably harsh sentence of ten years in prison.

The secret fund from which the money was embezzled had been controversial even prior to the joint FBI and IRS investigation that eventually brought down Chief Hart and former Deputy Chief Weiner. The fund was intended to be used for undercover police operations including drug buys, stings, and payments to informants. The first major scrutiny over the use of the fund came in 1980, when attempts by city auditors to review its expenditures was rebuffed by Chief Hart and Mayor Coleman Young, who claimed that its uses must be kept confidential for the safety of undercover officers and police informants. The following year, a city auditor managed to obtain documentation showing that a large appropriation from the Secret Service Fund had been used to install additional security features on Coleman Young’s private residence. In response to calls for further investigations of the fund’s use from members of Detroit’s City Council, Chief Hart assumed total administrative control over the fund. The move gave Hart the power to rebuff oversight attempts by refusing to deliver documents regarding the fund’s use. Although auditors and City Council members made additional efforts to monitor expenditures from the Secret Service Fund during the following years, they were largely unsuccessful in exerting meaningful oversight or control over it.

The FBI and the IRS investigation into the fund began in 1989 as a result of information obtained from former Deputy Chief Kenneth Weiner. At the time, Weiner was cooperating with the FBI after having been convicted of a litany of corruption charges relating to a variety of corrupt financial schemes he had been involved in during his time as Deputy Chief of Police. Weiner told federal investigators about the misuse of the secret police fund and allegedly indicated that Mayor Coleman Young had been involved in some capacity.

As the investigation got underway, federal agents were met with stiff resistance from Chief Hart and the Mayor’s office. Mayor Coleman Young had long been under the belief that the FBI was targeting him and those in his inner circle for political reasons. That belief was not entirely unfounded—the FBI had been surveiling Young because of his left-leaning political affiliations since the late 1950s—but, unfortunately for Coleman Young’s reputation, neither were the allegations against Chief Hart. Although Young’s refusal to cooperate with federal investigators never resulted in any criminal charges against him, it certainly reflected poorly on his administration. Already facing the indictment of William Hart, a long-time political ally and one of his first major appointments as Mayor, Coleman Young also had to respond to public allegations from federal agents that he had worked to stonewall their investigation.

The charges against Hart and Weiner were damning. In total, Hart wrote 98 fraudulent checks from the Secret Service Fund, all of which were payable in cash. He allegedly had employees cash the checks and give the money to a high ranking member of his staff, who then returned the cash to Hart. It was also revealed that during the probe Hart had attempted to convince a witness, a woman named Andrea Jeaneen Henry, to lie for him. Hart and Henry were in an extra-marital relationship and investigators were looking into whether Hart used the fund money to pay off Henry’s mortgage. The exposure of his infadelity added an additional element of public humiliation to an already dire legal situation. Kenneth Weiner, for his part, funneled additional dollars out of the fund using several shell corporations he had created to facilitate his illicit financial dealings. Investigators alleged that Hart and Weinerhad each stolen nearly $1.3 million in public funds. Over the course of the 1980s the city had appropriated nearly 10 million dollars for the Secret Service Fund. Hart and Weiner had collectively embezzled roughly a quarter of that total. So much money had been stolen that several of the DPD divisions that were supposed to be receiving the money were directly impacted. The internal affairs and organized crime sections especially felt the effects of the missing funds. Narcotics too was affected, with undercover drug officers reporting that they had been forced to use their own money to conduct certain drug buys.

Sources:

United States v. Hart, No. 92-2144, 6th Circut (2006).

Coleman A. Young and Lonnie Wheeler, Hard Stuff: The Autobiography of Coleman Young, (Detroit: Viking Press, 1994).

Detroit News, News Bank - Access World News.

Detroit Free Press, ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

Gimlet Inc. Crimetown, Episode 8, "Operation Backbone."