Mission and Research Ethics

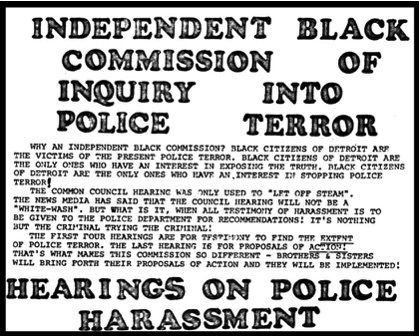

The main mission of the Detroit Under Fire project is to excavate and document the often deliberately hidden history of police violence and to make these stories, and the archival records that they are based on, available to public as well as scholarly audiences and especially to impacted communities. The second and equally important goal is to document the sustained activism and resistance of Black residents of Detroit, and of civil rights organizations more broadly, to police brutality and discriminatory law enforcement policies and practices. Please see the Politics and Silences in the Historical Archive page of the Overview section for elaboration of the particular challenges of carrying out a research mission shaped by the state's deliberate distortion and falsification of the historical record, and by other archival silences as well.

Black Lives Matter and State Violence. This project, and the Policing and Social Justice HistoryLab itself, emerged from the immediate context of the Black Lives Matter protests that followed the fatal police shooting of Michael Brown in 2014 in Ferguson, Missouri. The Black Lives Matter movement brought increased awareness of the reality that even basic information about the total number and incident details of police homicides in our current time is extremely hard to excavate and deliberately hidden from the public by government agencies, leading to a proliferation of activist efforts to document the full scope of fatal shootings by law enforcement officers in the contemporary United States. As Patrick Ball, a scholar of state violence, argued in Granta, "it is difficult to collect information about violence committed by governments" because agents of the state "make every effort to disguise their actions," leading to systematic undercounts of the actual scope of police killings and distorted accounts of what actually happened in incident reports produced by the agencies that committed the violence and media stories that primarily rely on those same agencies. What is true for our current moment is even more difficult to excavate for the increasingly distant past.

The Detroit Under Fire team began with a straightforward research question that turned out to be not only difficult but impossible to answer in full: how many people did the Detroit Police Department kill during the modern civil rights era, who were they, and what were the circumstances of their deaths? The project expanded into a much more comprehensive investigation of police power and civil rights/black power activism in Detroit, both because of the profound archicval silences and distortions around the identities and circumstances of individuals killed by law enforcement, and because of the incredibly rich archival documentation of activist campaigns against police brutality, misconduct, and broader policies of racial criminalization in the history of modern Detroit.

Project Subject Position and Public Mission. We, as a project team, acknowledge our subject position as privileged researchers from a wealthy and unequal public university that has had a historically troubled relationship with the city of Detroit, and as a diverse but also majority-white group of researchers, half of whom grew up in Michigan but none of whom are from Detroit. One of our project's main goals is to take advantage of the historical resources that our research team has access to--most of which are contained in archives open only during Monday-Friday work hours or in expensive digital databases that require institutional subscriptions--and make as many of these documents as possible available to public audiences and members of directly impacted communities who may be unable to examine them otherwise. Therefore, while the history recounted in this exhibit is shaped by our interpretations and analysis, the reproduction of more than 1,500 archival documents on exhibit pages and through interactive maps also allows audiences to carry out investigations of your own.

Research Ethics and Decisions about Disclosure vs. Anonymity. Documenting state violence raises difficult questions of research ethics, especially when the available sources involve trauma and are often tilted toward the law enforcement perspective, criminalizing the Black residents of Detroit in particular. At the same time, many of the non-state accounts of police brutality and misconduct that our research has uncovered came from regular people who--often at significant risk of police retaliation--filed formal complaints with the DPD's notoriously ineffective Citizen Complaint Bureau, wrote letters recounting violations of their rights to elected officials, sent accounts of what happened to the NAACP or the Michigan Chronicle (Detroit's African American weekly), requested investigations by government civil rights agencies such as the Detroit Commission on Community Relations and the Michigan Civil Rights Commission, and filed civil lawsuits against the DPD. In almost all cases, our project has made the research ethics decision to include the names and identifying information of people who filed complaints of police brutality and misconduct with these agencies and organizations, rather than reproduce the power of state violence by silencing or censoring their stories. The exceptions involve victims of sexual assault and rape who did not intend for their complaints to become public; a small number of juveniles whose experiences are recoverable from the archives but not from newspapers or other public records, and juveniles who were witnesses to police homicides and testified or spoke to police under duress.

Note on Racial and Gender Identity. Throughout the exhibit, victims of police violence are identified by their presumed racial and gender identities as well as by age and other categories, when relevant. Doing so is important for analyzing the broader patterns of police violence as well as for telling individual stories--people who appear in the archives often identified themselves through categories such as a Black mother filing a complaint on behalf of a teenage son, a Black husband and father whose family faced police harassment, a Black male racially profiled while driving, a Black woman abused during a traffic stop or in a precinct station. (Black residents of Detroit and the news media also often used 'Negro' during this era; the Detroit Police Department quite often used the outdated racial designation "colored" in its internal records). But in other cases, especially involving brief police and media reports about fatal shootings, the racial and gender identifications of the people involved are based on categories determined by law enforcement actors and are difficult or impossible to confirm independently. The exhibit notes the instances when the state's imposition of racial and gender identities on historical subjects seems questionable but otherwise uses the racial (Black/white) and gender (male/female) categories found in the archival documents, with the recognition that in some cases this will almost inevitably reproduce assigned identities that the historical actors would not have used to describe themselves. Additionally, the Detroit Police Department and the media rarely identified people outside of a Black-white binary during this era; members of the city's relatively small Latinx population were often classified as white, sometimes as Black, or otherwise labeled as 'Spanish,' 'Mexican,' 'Mexican American,' 'Latin,' or 'Latin American.' (Some Latinx subjects also self-identified as white, Black, or biracial).

Contact. Please send a message to detroitunderfire@umich.edu if the identity of yourself or someone you are related to is disclosed in this exhibit and you would like to request that it be redacted/removed, or if you have a personal story that you would like to add to this project or that is documented here but you believe should be revised, or for any other reason. Readers are also welcome to contact Professor Matt Lassiter, the director of the Policing and Social Justice HistoryLab, with any and all such inquiries at mlassite@umich.edu.