Untested Rape Kits

In 2009, a Wayne County assistant prosecutor discovered the existence of 11,219 rape kits, abandoned by the Detroit Police Department (DPD) in a dilapidated evidence warehouse. While over two thousand of those kits had markings indicating they had been submitted for testing, investigators were unable to determine if that testing had ever been conducted. The vast majority, nearly 9,000 kits, had never even been submitted at all. Those abandoned kits, the oldest of which dated back to 1980, represented nearly 30 years of sexual assault cases that Detroit police had failed to sufficiently investigate.

Origins

A rape kit, also known as a sexual assault kit, is a set of tools used to collect and store forensic evidence samples from the body of someone who has experienced sexual violence. The administration of a rape kit is often invasive, uncomfortable, and traumatic for victims, especially because it must be administered in the immediate aftermath of their assault. That so many women in Detroit were made to undergo that experience, just to have their kits left abandoned an untested for decades, is a testament to the callous approach that many in the DPD took in regards to investigations of rape, sexual assault, and violence against women in general.

The rape kit was invented in the mid-1970s by feminist activist Marty Goddard, however, its administration only became common procedure in hospitals starting in the late 1970s and early 1980s. When coupled with the fact that the oldest abandoned rape kit discovered in Detroit was from 1980, that history leads to an important conclusion: at the very moment that rape kits were being introduced, Detroit police were already failing to test many of them.

The fact that Detroit police officers in the 1980s did not follow through on many sexual assault investigations may be somewhat unsurprising given the myriad other ways in which the DPD at the time demonstrated a lack of respect and concern for women and victims of sexual violence. Yet the practice of leaving rape kits untested did not end in the 1980s. It’s continuity over nearly three decades demonstrates that the failure to properly investigate cases of sexual violence was a constant characteric of the DPD for that entire period.

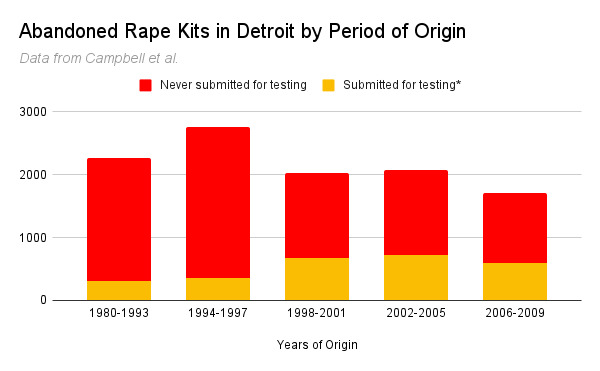

In the aftermath of the discovery of the untested rape kits in Detroit, the city commissioned a team of researchers to start the Detroit Sexual Assault Kit Action Research Project. Members of the Action Research Project were tasked with carrying out a census of the discovered rape kits and creating a report on what had gone wrong. The following chart uses data from that census to show the number of rape kits in the possession of Detroit Police and the period from which those kits originated. Note that the first column represents a period of 13 years whereas each subsequent period is only 3 years.

“Minimal Investigational Effort”: Why So Many Rape Kits Went Untested

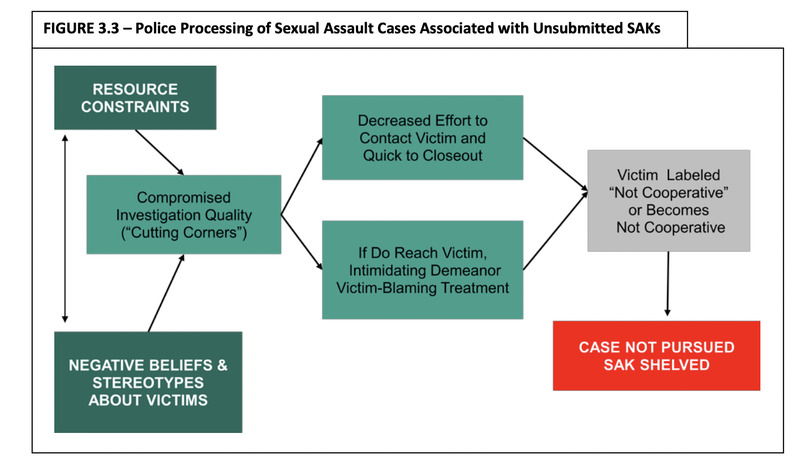

In trying to determine how and why so many rape kits had gone untested for so long, the members of the Action Research Project conducted an extensive analysis of the DPDs internal structure, performed an audit of a sample of sexual assault cases, and interviewed a variety of personnel within the DPD. Their review identified several underlying causes behind the lack of attention given to cases of sexual violence by the DPD. According to the Action Research Project report, those causes included “chronic understaffing and resource depletion,” as well as the disturbing tendency among law enforcement to express “negative, victim-blaming beliefs about sexual assault victims.”

Even prior to the introduction of rape kits, the DPD did not devote sufficient resources to handling accusations of sexual assault and violence against women. Far from an incidental result of general scarcity in the city’s budget, the lack of funding and staffing dedicated to dealing with gendered violence was an intentional policy predicated on widespread sexist beliefs in a police department that was, and still is, predominantly male in its membership and leadership. Even as feminist activism in the 1970s and 1980s forced the DPD and the City of Detroit to take sexual assault more seriously, the organizations charged with responding to cases of sexual violence still suffered nearly perpetual underfunding and understaffing. Groups such as the DPD Sex Crimes Unit, the city’s crime lab, hospitals, and other service providers for victims of sexual violence all “functioned under chronic resource depletion” for decades. While that lack of resources undoubtedly contributed to the DPD’s failures in responding to sexual assault, it was certainly not the only factor. The DPD as a whole struggled with funding issues and low resources at various points in its history, yet those problems never resulted in a comparable backlog of other types of forensic evidence. The Action Research Project confirmed this, its report stating: “no statistical association between staffing cuts [in the Sex Crimes Unit] and [Sexual Assault Kit] submission rates, which suggests that there were other factors at play.”

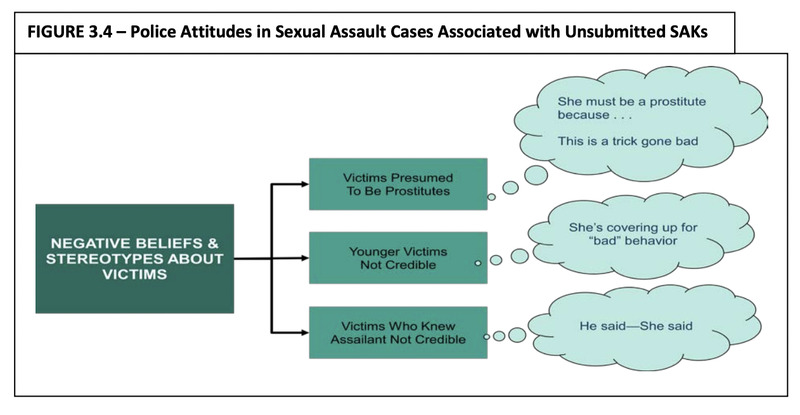

As the Action Research Project report makes clear, other factors contributing to the DPD’s chronic failure to properly investigate sexual assault were longstanding sexist attitudes as well as “negative beliefs and stereotypes about victims [of sexual violence].” During the 1970s and prior, sexual and domestic violence were explicitly regarded as a low priority within the DPD, precisely because they were crimes that primarily affect women. Patriarchal and misogynistic assumptions often informed the police response to sexual violence. Unlike with other crimes, police suspicion in sexual assault cases immediately fell back on the victims, so much so that rape victims were routinely given polygraph tests as late as 1980. Although feminist activists won some victories during and since the 1970s, changing official policies to encourage a greater police response to violence against women, sexist biases in police culture remained evident.

Through interviews with members of the DPD and a review of past sexual assault investigations, the Action Research Project found that male officers frequently found reasons to downplay or cast doubt on the accounts given by victims of sexual violence. Officers routinely employed victim blaming, acting dismissively in cases when a complainant knew the offender, or when they suspected that a complainant had been engaged in prostitution. The treatment of young victims by police was particularly egregious, with many officers alleging in police reports that adolescent victims had fabricated their accounts of being assaulted to avoid taking responsibility for “bad behavior” such as staying out too late. These tendencies also impacted the way that DPD officers directly treated victims of sexual violence. In some cases officers overtly intimidated victims by antagonizing, interrogating, and even threatening them during interviews.

As a result of victim blaming and hostility in police treatment of victims, many sexual violence cases were prematurely closed before being properly investigated. The two most common justifications given by Detroit police officers to prematurely close sexual assault cases were to reject the legitimacy of the complaint (by claiming that the victim was untrustworthy or that there was insufficient evidence to show that a crime had occurred, even when police had made no effort to locate such evidence using information provided by the victim) and to assert that complainant was not willing to pursue charges (by claiming that the victim was unavailable or non-cooperative, even when officers treated victims with hostility and actively discouraged pursuing charges). Officers often used the scarcity of resources to justify their own investigative failures, claiming that they could only afford to look into the cases they perceived as most viable and legitimate.

Finally, the Action Research Project noted that an intersectional approach is useful in understanding police responses to sexual assault. The Detroit residents most vulnerable to sexual violence were Black women, and many of them were poor or working class. The convergence of sexist, racist, and classist biases among DPD officers was clearly reflected in their dismissive handling of sexual assault cases. The result was that victims, who were often poor or working class Black women, were exceedingly less likely to receive justice in the form of police intervention against their assailants.

Sources:

Detroit Free Press

Pagan Kennedy, "The Rape Kit's Secret History," New York Times, June 17, 2020

Rebecca Campbell et al. "Final Report- Corrected," Nov 9, 2015, THE DETROIT

SEXUAL ASSAULT KIT (SAK) ACTION RESEARCH PROJECT (ARP), NCJRS, https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/248680.pdf