Patterns of Police Homicides

NOTE: This page is in development and the data and details should not be used or cited under any circumstances. The research project has identified at least twice as many police homicides for this time period as included below and is in the process of validating all of the data.

Patterns in Police Homicides

Police homicides in the early 1990s mirror patterns from earlier decades. Each identified homicide was in or very close to a primarily African American neighborhood and most were on or near the border between white and black neighborhoods. It is likely that these neighborhoods consisted of middle-class African Americans who were unaccustomed to experiencing police violence in their neighborhoods, making them more likely to report these homicides that they viewed as cruel and unusual. More homicides went unreported within poorer neighborhoods because police violence within these neighborhoods could have been viewed as almost commonplace. A public reaction among middle-class African Americans would generate a media response, whereas outcry from the poorest neighborhoods in Detroit was unlikely to receive any attention. This showcases how homicides are more likely on the borders of these different groups, possibly due to police using excessive force in order to protect the “good community” from the marginalized communities they’ve already criminalized. This really highlights how income is much more of a community indicator for this later time period than race due to “white flight”. This is to be expected because by the 1990s, the city of Detroit was less racially diverse as it was in the 70s and 80s. As a result, different income levels do a more effective job of differentiating communities than race would for this time period. Most of the homicides are located near at least one other homicide, indicating certain geographic “hotspots” of police brutality. Although there are a few on the map, we also notice a significantly lower amount of homicides in the impoverished southwest area of Detroit. This lack of incidents is not likely from the actual absence of police violence, but more likely the result of lack of reporting and police accountability. Areas such as southwest had terrible police-community relations at the time due to police corruption, gang activity, and the constant over-policing/under-policing as youth was criminalized. This likely led to a lack of reporting, and allowed for the police to run uncheck particularly in that part of town.

Of the 16 homicides that we have identified from 1990 until 1993, an alarming percentage have been justified or attempted to be justified by the police claiming that the person was a suspect in a crime or was carrying a weapon that posed a threat to the officer’s life. In almost every death of a civilian, they are killed by gunshot with the very public exception of Malice Green. The officer then argues that the victim had a weapon of some sort, usually a gun or knife and the shooting was in self defense. Two officers claimed that the civilian was reaching for a weapon, but there was no weapon found on the scene. Five officers claimed that they saw a weapon or the suspect looked like they had a weapon, but the civilian was later found to be unarmed. Six of these homicides were of people who were suspects in a crime, some of which were found not to have been the correct suspect. The more than half of the civilians killed by police were said to have had a weapon, but this statistic is likely skewed. A conversation with a Detroit Free Press reporter, Joe Swickard, revealed a troubling pattern of “dropsy” incidents, when civilians were said to have dropped the contraband on the ground and the officer could rightfully suspect that it had belonged to them. It is possible that some or many of these homicides had weapons planted at the scene. There had even been an alleged discussion among officers about planting a gun in Malice Green’s car. Additionally, even after the federal law prohibiting police from shooting suspects who were fleeing, there were five instances of police homicides of fleeing suspects. The consistency in this pattern throughout the late 20th century is remarkable. Officers could also avoid discipline by claiming that the shooting was an accident, as two officers did during this time period. The number of homicides that were justified or attempted to be justified in almost identical manners indicates a troubling pattern of police abandoning responsibility for the lives that they had taken.

Police Homicide Incidents (1990-1993)

A document that we recovered from the archives that came from an Inter-Office Memorandum gave statistics about shootings by police from September of 1991 to September of 1993. While this does not cover our entire time period, it represents a large portion of it. During this portion, there are 25 fatal police shootings reported by the DPD. We have only identified 15 of these, as the last is the beating death of Malice Green. This report covers exactly half of the months in our time period, meaning that if the shootings were to happen at a statistically constant rate, the total amount of fatal shootings would be 50 in our time period. That would mean we have only uncovered 30%. This indicates a deliberate attempt of the DPD to keep instances of police shootings within the department, and not to give details to the media. The report also does not account for police homicides by other means, so the number could be even higher. In Joe Swickard and David Ashenfelter’s expose of the excessive use of force in the DPD published in 2000, they estimated an average of ten police homicides per year in the early 1990s. This would indicate that there were 40 homicides during this time period, meaning that we have only identified 40% of homicides. We will never know the actual number of police homicides due to inaccuracy of reporting and the deliberate concealment of information, but if these estimates are close to correct, violence within the department was rampant, and information about it is scarce.

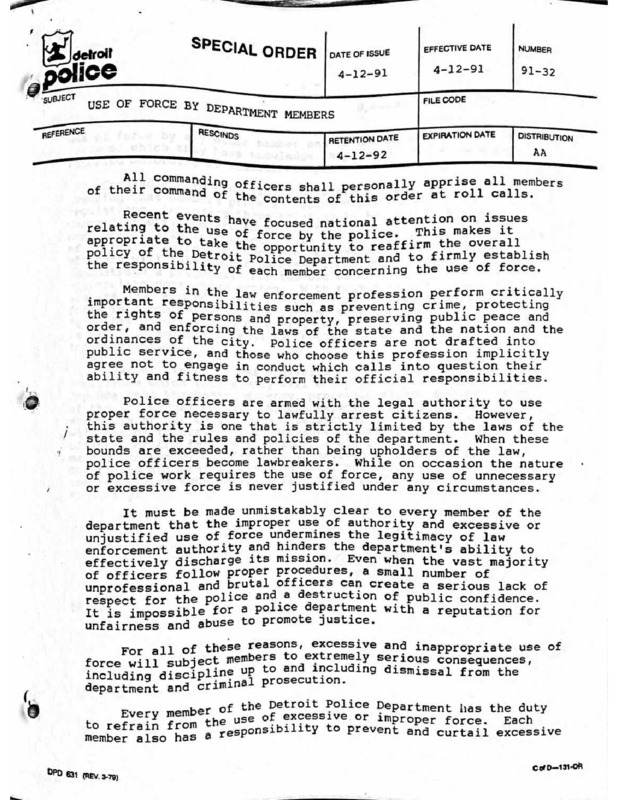

During the early 1990s, the use of force policy was largely a non-issue before the fatal beating of Malice Green. Shortly after his death, the DPD’s policies were examined in-depth, or at least that is how the department portrayed it to the public. This resulted in changes to the tools that officers carried on them and the introduction of plastic flashlights and mace (link). Even after the federal law had changed to prohibit officers from shooting civilians in the back, this pattern still prevailed. A special order published by Stanley Knox in 1991 that gives an overview of the use of force policies in the department and what should happen if those were to be violated. He takes a stance of strict authority and denounces any use of excessive force by officers. He charges officers with the responsibility to not violate these policies and to keep others from violating the policies. He requests that supervisors properly discipline officers that use excessive force and that commanding officers remind officers of their policies and how to avoid using excessive force regularly. Near the end of the report, he mentions that officers who do not report uses of excessive force will also be punished, which indicates that there have been instances of officers shirking their responsibility to report in the past. He refers to the laws of the state and the police department as the guiding factors in making disciplinary decisions, but does not explicitly say what these are. Knox also mentions that even if the use of excessive force within the department was a result of “a few bad apples,” it was still unacceptable. However, we can infer from the information we have found about officers being exonerated that there were typical circumstances that could be cited to indicate that the officer’s life was in danger, which would give them a right to use force. This could be the appearance of a weapon on the civilian or apprehending a suspect of another crime, both of which we see consistently. These patterns suggest that the policies within the DPD are at fault for the numerous police homicides in the early 1990s. This is an open debate, however, because the number of officers involved in more than one police shooting from September 1991 to September 1993 is 18. This is a small portion of the force, but still a significant number.

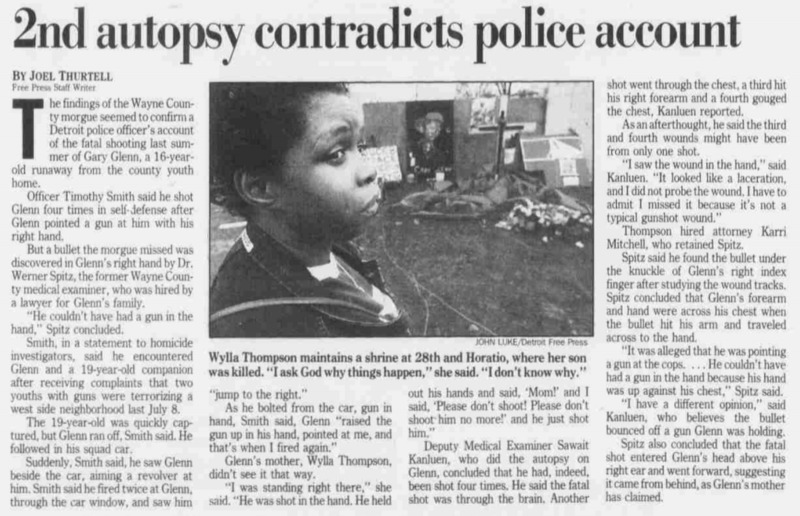

Gary Glenn

On July 8, 1993, Gary Glenn was shot and killed by Officers Timothy Smith and Phillip Ratliff while allegedly pointing a gun at the officers. Glenn was with a friend who had been apprehended by the police, and while Glenn was fleeing, Smith shot at him once from the police car and hit him in the abdomen. When Glenn allegedly held the gun up, Smith fired twice more. After the shooting, an angry crowd gathered and protested the violence. Two guns were alleged to have been found at the scene. A preliminary hearing found the shooting justifiable, so Smith and Ratliff were suspended with pay. Later, the medical examiner found a bullet lodged in Glenn’s hand and concluded that Glenn could not have been holding a gun. There is also evidence that the fatal shot came from behind. Glenn’s relatives filed a $15 million lawsuit against the City of Detroit, Police Chief Stanley Knox, Smith, and Ratliff. They claimed that Smith and Ratliff should have had more training in how to use nonlethal force.

Dartavian Sampson

On November 26, 1990, Officer Brian Fields of the DPD shot and killed 29-year-old Dartavian Sampson. Sampson and his friend, Lucien Major, were suspects in a shooting and robbery that had occurred moments earlier. The pair was alleged to have fled the scene of the crime. Officer Corleen Sewell was also involved in the chase, but was not the one who fired the fatal shot. When Sampson and Major were apprehended, the officers put them on the ground to handcuff them. Fields shot Sampson in the back after Sampson was alleged to have moved his arm, as if reaching for a weapon. It was later confirmed that Sampson and Major were not the suspects that the police were looking for and that Sampson was unarmed. Fields was found guilty of negligent discharge of a firearm resulting in great bodily harm and was sentenced to two years of probation, a lesser sentence that his original charge of voluntary manslaughter would have warranted. Sampson’s family filed a $10 million lawsuit and won.

Donzell Dean

On November 29, 1991, Officer Barton Mitchell shot Donzell Dean, who later died from his injuries. Dean was fleeing in a car during a drug raid of a house nearby. He was 31 at the time of his death. Four uniformed officers, all part of the narcotics squad, were raiding a suspected dope house when Dean tried to escape as a passenger in a car. The driver, Craig Carter, had arrived with Dean at the house at around 12:55 am. Dean exited the car, but when he heard screaming, he got back in. They tried to drive away when Mitchell shot at the car twice, shattering the back window and leading to Dean’s death. Carter called EMS but Dean was dead upon arrival at the hospital. The officers did not have a warrant to search the house and did not end up making any arrests. Mitchell then waited three hours to report the shooting, which was against department rules. The three other officers involved were demoted to administrative positions. Mitchell was acquitted because he said that he thought the shooting was a flashback or dream to when he had killed another civilian in May of 1990.

Thomas Ladell Walker

Thomas Ladell Walker was found shot in the head on January 4th, 1992 in his east side home after an hour-long standoff with the police. Reports do not specify whether Walker was killed by police or if he committed suicide.

Unidentified Male

On November 1, 1993, an off-duty officer shot and killed an unidentified man at Barber Elementary School. The man was alleged to have caused a disturbance in the school before revealing a gun. He did not shoot anyone inside the school.

Unidentified Male

An unknown suspect held up a Society Bank and Trust co. in Toledo, Ohio and was apparently chased north on I-75. He stopped near the Elm Street exit in Monroe. After he stopped, shots were exchanged and the unknown suspect was fatally hit with at least one bullet around 3 pm. The outcome of the incident was not reported in the media.

Eric Ward

On Thursday, December 12th, 1991 Eric Ward was fatally shot by two police officers. Eric Ward was a 17-year-old who escaped from a Juvenile Detention called W.C. Maxey Boys Training School center near Whitmore Lake. Two officers were responding to a complaint that someone was firing a gun. Ward allegedly failed to obey an order to drop his “weapon.” After the fatal shooting, it was apparent that all Ward had was an air gun that looked like a .45 caliber handgun according to the police.

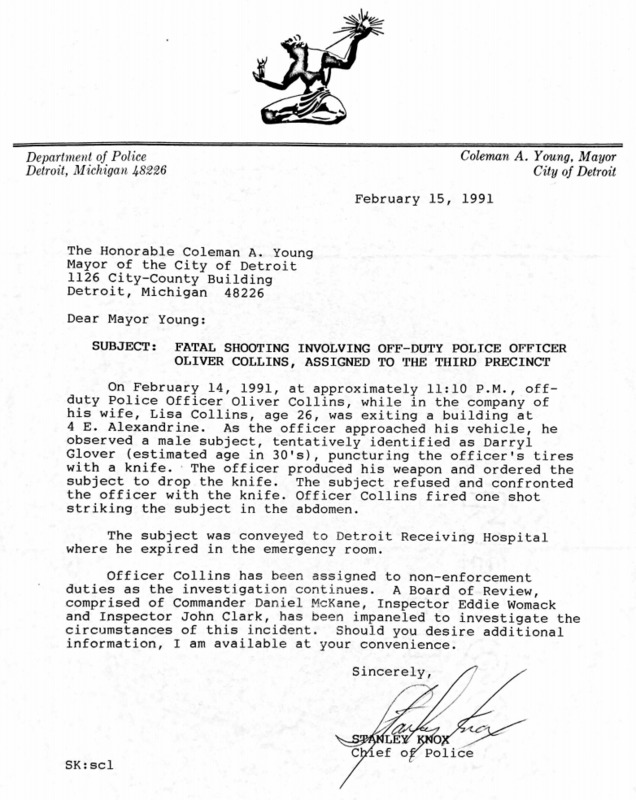

Daryll Glover

On February 14, 1991, Officer Oliver Collins, while off-duty, shot and killed Daryll Glover, who had a history of mental illness. Collins walked out of a restaurant with his wife Lisa on Valentine’s Day and saw a man putting holes in the tires of his car with a knife. Collins ordered the man to drop the knife. When Glover did not drop the knife and allegedly confronted Collins with it, Collins shot Glover once in the abdomen. Glover died in the hospital from his injuries. A Homicide Inspector said that the shooting seemed to be justified, but a witness claimed that Glover did not have a knife because his hands were open. Another witness, a security guard, claimed that he did have a knife. Later, Collins stated that he regretted the shooting.

Andre Amos

Officer Terry Murphy shot and killed 26-year-old Andre Amos on March 20, 1990. A witness and neighborhood resident, Shirley Baldwin, said that she was talking with another woman when she saw a Ferndale police vehicle go down the street, and soon after she heard gunshots. The police had been chasing Amos from a janitorial supply store, Crandall-Worthington Co., after he was suspected of stealing $500 while armed. The Detroit Free Press describes the neighborhood that Amos was shot in as full of drug dealers and prostitutes, and as a “dumping ground for truckers.” The officers fired eight shots at Amos, but the police claim to not know who fired the deadly shot. Another witness said that he watched Amos die and did not see a gun near him.

Terry Grayson

A shoot-out occurred inside a Detroit Nightclub at 2 a.m, Black Orchid Club, were off-duty deputies were in. A man named Terry Grayson, aged 27, was walking past the deputies when he accidentally spilled an ashtray. Grayson apologized and the officer turned around and saw a gun being pointed at him. This is when shots were being exchanged. One of the officers fired, striking Grayson in the head. Grayson was found dead a block away.

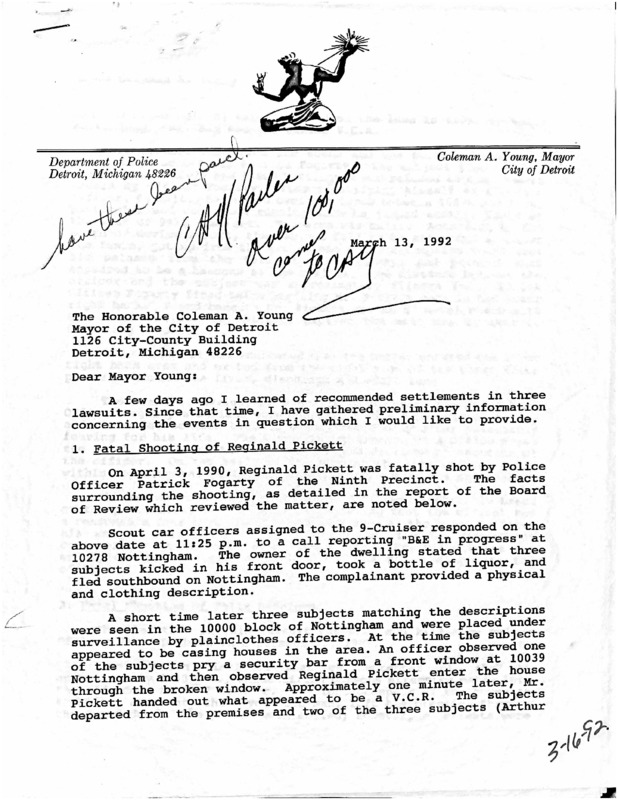

Reginald Pickett

On April 3, 1990, Officer Patrick Fogarty of the Ninth Precinct shot and killed Reginald Pickett. Fogarty claimed that Pickett matched the description of a man who had broken into a home and taken a bottle of liquor before fleeing. Shortly after the break-in, the officers watched three men who matched the given description of the suspects allegedly use a crowbar to break into another house. Pickett entered the house and handed a VCR to the two other men. When they saw the officers, Pickett allegedly attempted to flee. Fogarty chased Pickett, who jumped a fence and fell to the ground. When he got up, Fogarty claimed that Pickett was holding something that looked like a handgun. Fogarty shot Pickett twice; the shot that killed him was in his lower back. There was no gun at the scene and Pickett died at the hospital. The Board of Review found that Fogarty’s actions were in line with department procedures because he feared for his life. His family was awarded $375,000 in a lawsuit in 1992.

Unknown Youth

Detroit Police shot a 17-year old teen in the 4100 block of Rohns on the east side. The teen was pointing a gun at two police officers, one of the police officers shot the teen in the shoulder. The teen dropped the gun, ran away, but the police caught him. The youth was not publicly named.

Thomas O’Bryant Scott

On May 27, 1993, Sergeant Claudia Barden shot and killed Thomas O’Bryant Scott while conducting a drug raid on a house. Barden was alone and entered the house with her weapon drawn, where she found Scott asleep. She woke Scott and brought him with her throughout her search. When they were in the kitchen, Barden shot Scott in the back as a result of his alleged attempt to flee. She told another story in which Scott hit her arm and that is what caused her to pull the trigger. The results of the autopsy suggest that Barden shot Scott in the back while he was leaning over. There were no charges brought against Barden as of four months after the death. There were also no drugs or alcohol found in Scott’s system, and he was unarmed. His mother complained in a letter to Knox that she was not notified about her son’s death until much later and that they would not give her any or accurate information when she contacted the police and the morgue. She accuses the police of hiding the truth about what happened to her son and cites a probable cause of the officer being African American as well as the victim.

Malice Green

Malice Green was dropping his friend off when he was pulled over by an unmarked police car and asked to show his license. He did as he was told, then the two DPD officers beat him with their flashlights. When more police arrived, they continued to beat him. He was pronounced dead at the hospital. See the IN-FOCUS page for more information.

Marcus Chapman

On July 10, 1993, Marcus Chapman was shot in the back of the head by a U.S. marshal. There were two agents involved, but neither were publicly identified. Chapman had was being held as he awaited trial for drugs and weapons charges in West Virginia. Upon notification of his escape, U.S. marshals placed the home of his relatives in Detroit under surveillance. When they saw Chapman exit the home and get in a car with three other people, they began to follow him. When they pulled the car over and handcuffed Chapman, he allegedly pulled out a pistol. Official reports state that Chapman was shot with his own weapon during a struggle, but a 14-year-old witness claimed that Chapman was handcuffed and lying prone when the agents took a pistol from him. The witness said that Chapman tried to flee, and that is when he was shot by police in the back twice, before even being told to freeze. The agents were not taken off the streets, but reports said that the incident was being investigated. This incident occurred only a few days after the death of Gary Glenn.

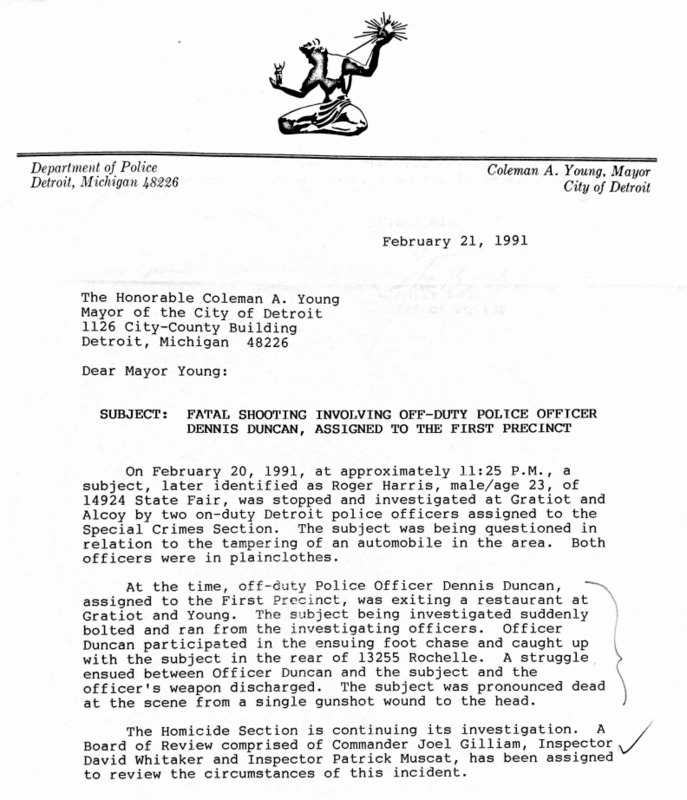

Roger Harris

On February 20, 1991, Officer Dennis Duncan shot and killed Roger Harris after stopping him to question him. Duncan and another officer, both in plainclothes, were interrogating Harris about a nearby auto crime when Harris allegedly fled. Duncan and Harris became engaged in a physical altercation when Duncan’s weapon was fired and Harris was shot in the head. The police report does not indicate whether or not the weapon was discharged accidentally or on purpose.

Jose Iturralde

Iturralde had been stopped by police when he cursed at them in Spanish and allegedly reached for a gun. Officers Ira Todd and Rico Hardy fatally shot Iturralde, a homeless Cuban immigrant, as he reached for the alleged gun. See more about this on the IN-FOCUS page.

Sources used for this page:

Coleman Young Papers, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

Board of Police Commissioner Minutes, Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library

The Detroit Free Press

The Detroit News