Drug Policies in Michigan

State-level policies were incredibly important in establishing models for policing and “crime reduction.” Not only did Michigan’s Governor at the time, James Blanchard, establish forums and committees to decide how the Anti-Drug Abuse Acts of 1986 and 1988 were going to function in Michigan, but his office also served as the mediator between the national War on Drugs and local city governments such as Detroit that would be following the leads of the higher levels of government. The federal anti-drug legislation gave Michigan 20 million dollars which was mandated to be allocated among three categories related to drug abuse: The office of substance abuse services, the department of education, and the office of criminal justice. While efforts were made in the fronts of educational and rehabilitation programs, the need for harsher punishments and more effective law enforcement ultimately led to the changes that had the most lasting effects. This federal money, as well as additional funds from the state, consequently funded the street-level war on drugs in urban areas through financing programs like Operation Crack Crime in Detroit, resulting in thousands of arrests on the basis of discretionary policing tactics and racial profiling.

Escalating The Hype and Involving Citizens

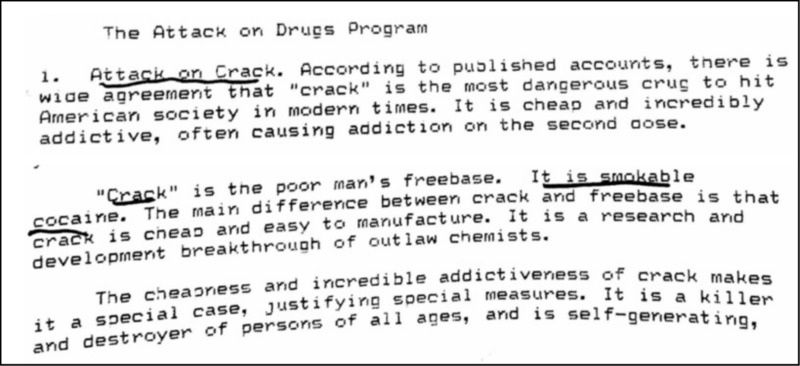

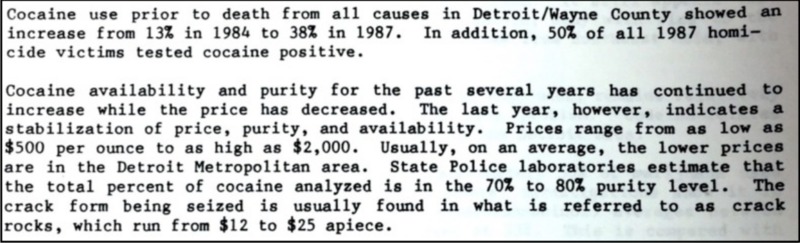

The Blanchard administration took largely the same approach as the federal government in terms of pushing a punitive shift in drug policy, significantly through the explicit separation of crack from powdered cocaine, playing off of the media perception that crack specifically was"instantly addictive"-despite this claim having no scientific basis. Blanchard's staff encouraged him throughout his terms to continue heightening drug policies and make them known so that the people of Michigan would be confident in their state police and government. While the federal policies were largely rooted in the concern of marijuana smoking among white suburban youth and a sensationalized perception of harder drug use, Michigan was somewhat more aware of the impact that cocaine was having within local communities. There were block grants established for certain areas that were seen to be at the highest risk of youth drug involvement- the city of Detroit being a primary receiver. Government officials further wanted to increase the involvement of citizens as active participants in the fight against drug use, following the national narrative of a collective effort while simultaneously escalating the notion of a crack "epidemic". Roy Hayes, U.S. Attorney for eastern Michigan set up a hotline where citizens could call about information and concerns in regards to cocaine- (313)-NO-CRACK. It was manned by DEA agents 24/7, and Agent Robert DeFauw stated that “confidentiality will be protected and rewards will be paid for information leading to arrests and convictions”. While it was commonly stated that crack was a problem facing all of society, it was also implied that certain groups of people were more likely to be involved with this “most dangerous drug” by calling it “the poor man’s freebase”.

Militarization of Michigan’s Police

The Blanchard administration's labeling of crack as the largest threat to American society, coupled with the acknowledgment that its inexpensive nature made it especially attractive in poor urban areas, led to law enforcement taking a militarized approach to policing primarily low-income areas. This was heightened by Blanchard's support of incentivizing legislation that allowed for asset forfeiture in drug-related crimes, causing a shift of precedence to drug crimes above all others for the profit motive. Michigan’s Public Act 135 of 1985 allowed for 100% of forfeited goods in drug arrests to be utilized by police to assist law enforcement efforts, which during that fiscal year equated to $5.5 million. The Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986 further produced federal legislation that expanded the scope of forfeiture laws, adding to the already bias policing determinants in place. As a result, Michigan State police became very active in drug raids across the state, especially through the creation of the State Police Drug Strike Force, which was deemed laudable by Blanchard and state officials as successful measures to combat the drug crisis. These tactics would trickle down to Detroit, with the formation of their own tactical raid squads through operation crack crime.

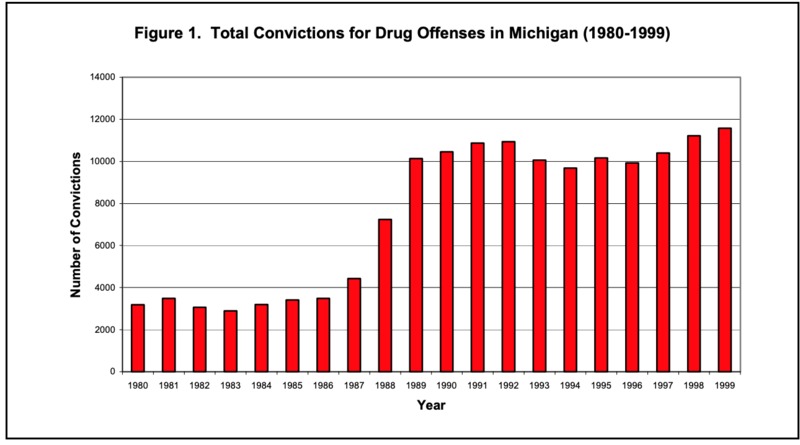

Such a specific targeting and aggressive tactics naturally elicited a gross increase in the number of arrests and convictions during the late 1980s, with new policies greatly influencing the significance of this. While the mandatory minimums set forth in the Anti-Drug Abuse Acts were controversial and criticized nation-wide, they were not new to Michigan in 1986. In 1978, the “650 Lifer Law” was passed which dictated a life prison sentence to anyone convicted of possession, distribution, or intent to distribute over 650 grams of cocaine. It further mandated a 20-30 year sentence for amounts between 225 and 650 grams, and incrementally lesser minimums for amounts less than 225 grams. While this was an attempt to get at the root of the problem by discouraging large-scale drug trafficking networks, it led to a sharp increase in convictions of individuals falling under the lesser quantity category, affecting drug runners and street dealers as opposed to king pins. These tough sentences were challenged in the late 80s by opposers who thought they were too strict- leading them to be reduced in 1988, but quickly reinstated in 1989, and were not repealed until 2002.

Blanchard Speaks To Committee On Justice and Public Safety, 1989

Bl

Blanchard’s Conflicting Narrative

In this Congressional Committee on Justice and Public Safety (see above), Blanchard took aim at the federal government for the large percentage of people who are in prisons for substance abuse-related incidents, pointing out that these facilities are greatly overcapacity and stating, "state and local judges are sending everybody that they find to prison, oftentimes people who should be in local jails or in some other corrective program." He argued that there is too much discrepancy in sentencing in regards to where a convicted individual will end up spending time, and a lack of consistency across government levels. However, while he may have spoken out against prison overcrowding, it wasn’t the sheer increase in prisoners that he was concerned about, as 18 new prisons opened in Michigan during Blanchard’s time in office. Even into 1990, Blanchard still viewed his policies to be under effective and expresses the need to create even tougher and more punitive laws to punish drug-related offenses. In reference to the 650-lifer law, Blanchard bragged to the director of the Office of National Drug Control Policy, "Michigan already has the toughest punishment in the nation for drug dealers-life without parole." but that Michigan still needed "even stronger laws to punish them."The new strategy in 1990, while including an increased effort to involve local communities, further expanded the police force to attack drugs at the ground level.

Sources:

Detroit Free Press, July, 1986

Blanchard Papers Collection. September 8, 1986. Box 19. Bentley Historical Archives, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Lieblich, Eliav & Adam Shinar. “The Case Against Police Militarization.” Michigan Journal of Race and Law 23, 1, 2018

Walker, Nancy., Villarruel, Francisco., Judd, Thomas., Roman, Jessica. “Drug Policies in the State of Michigan: Economic Effects,” East Lansing, Michigan: Michigan State Institute for Children, Youth, and Families. April, 2000

Affholter, Patrick & Bethany Wicksall. “Eliminating Michigan’s Mandatory Minimum Sentences for Drug Offenses,” Lansing, Michigan: Senate Fiscal Agency, 2002.

Blanchard, James. “Committee on Justice and Public Safety.” C-SPAN. February 29, 1989. Washington, District of Columbia, United

States. MPEG-4, 19:40.