Sex Crimes Unit

The Women and Children's Division (1921-1974)

The Detroit Police Department (DPD) started the Women and Children’s Division in 1921 specifically to address sex crimes and child abuse. This section was renamed the Sex Crimes Unit (SCU) in 1974.

The Women’s Division contained a staff of 71 female police officers. Until 1974, female police officers were confined to this division. These officers investigated and processed criminal complaints of sex crimes involving male victims under ten years old and female victims of any age (WD packet). The division also dealt with cases of child abuse and neglect, as well as noncriminal concerns such as wayward youth. These cases might have involved “misbehavior” by girls under the age of 17, such as shoplifting, arson, “immorality,” and attempted suicide. Female police officers were expected to primarily attend to the social problems of the individuals involved in these cases.

The Sex Crimes Unit

The national context around sexualized violence influenced the changing priorities of the DPD during the 1970s. In a 1974 report on rape in Detroit, the DPD highlighted the drastic rise of rape in comparison to other violent crimes. The report claimed that women living in the country’s 58 core cities have a 100 in 100,000 chance of being raped. In Michigan, the rape-risk-rate for women increased from 26.7 per 100,000 in 1971 to 35.1 per 100,000 in 1974.

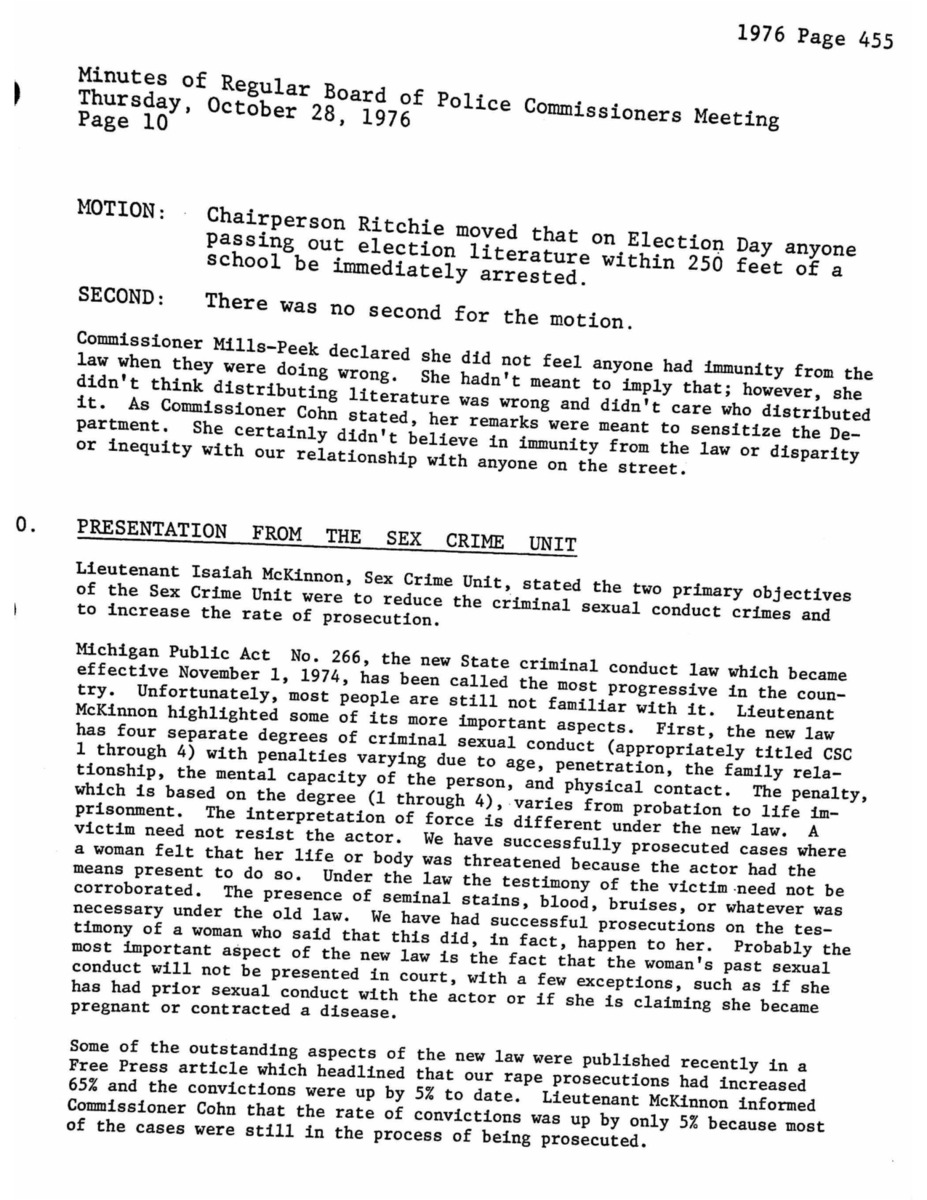

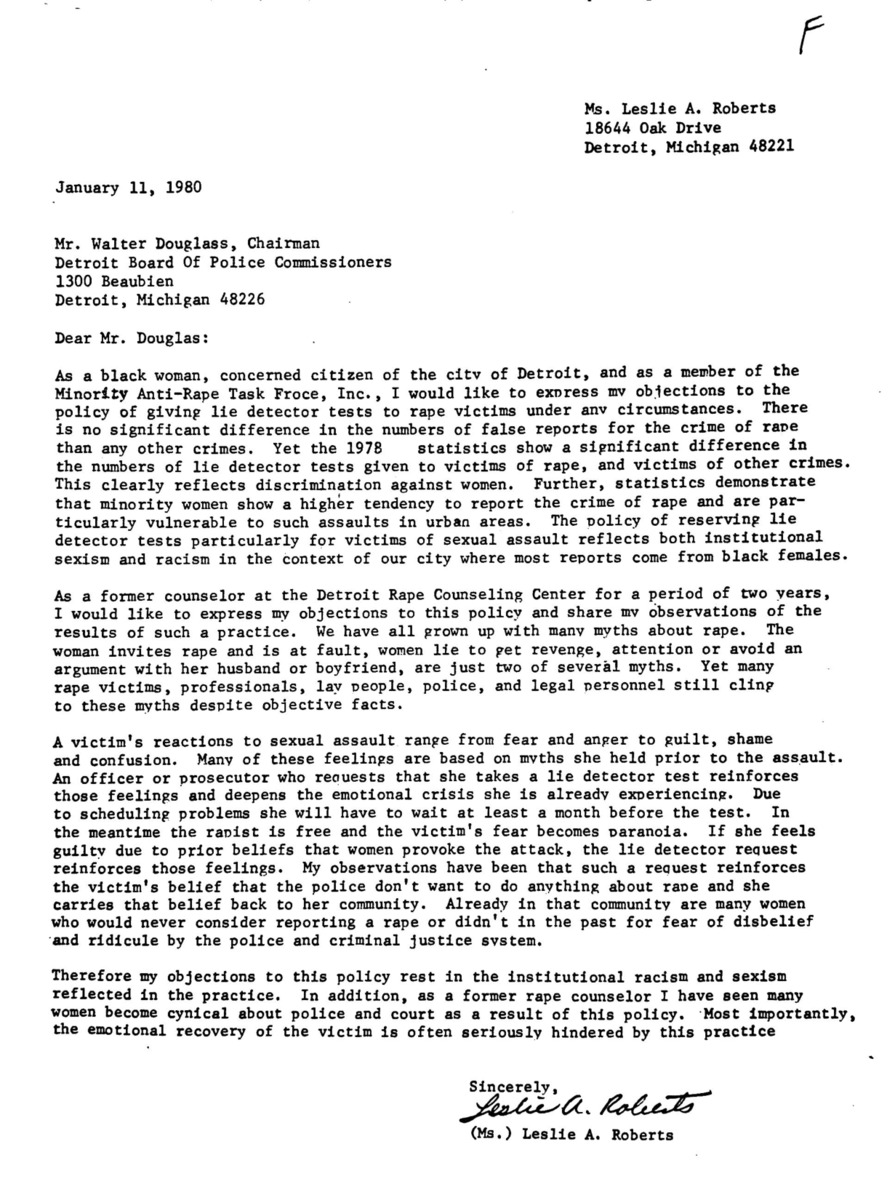

The newly formed SCU was responsible for the “investigation, apprehension, and prosecution” of sex crimes as defined under the Criminal Sexual Conduct statute. The Michigan Public Act No. 266, which became effective in 1974, established new criminal conduct law. The law recognized four separate degrees of criminal sexual conduct and corresponding penalties, varying from probation to life imprisonment. The law also revised the interpretation of force, declaring that women need not resist the perpetrator. The Act got rid of corroboration requirements for victim testimonies, as well as requiring the female victim’s sexual history to be presented in court. The SCU investigators worked with the Crime Analysis Unit to develop patterns of modus operandi and descriptions of sexual offenders, as well as to investigate severe rape cases like gang rapes and robbery armed rapes.

Housed within the SCU was the Rape Counseling Center (RCC). Founded in 1975, the center came under the auspice of the DPD in 1977 at the urging of city council members Erma Henderson and Maryann Mahaffey, as well as the National Organization of Women. The RCC staff were trained social workers that offered emotional support and tended to a victim’s trauma at the hospital or at the SCU. The staff also followed up with the victim throughout the entire court process and made referrals to other agencies that could offer additional care to victims. The social workers who worked within the RCC educated the police department and the public about sexual assault reporting and prevention.

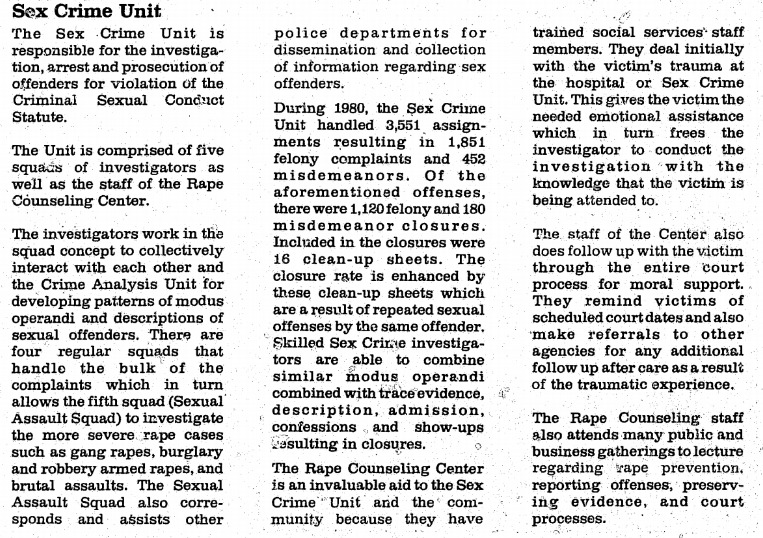

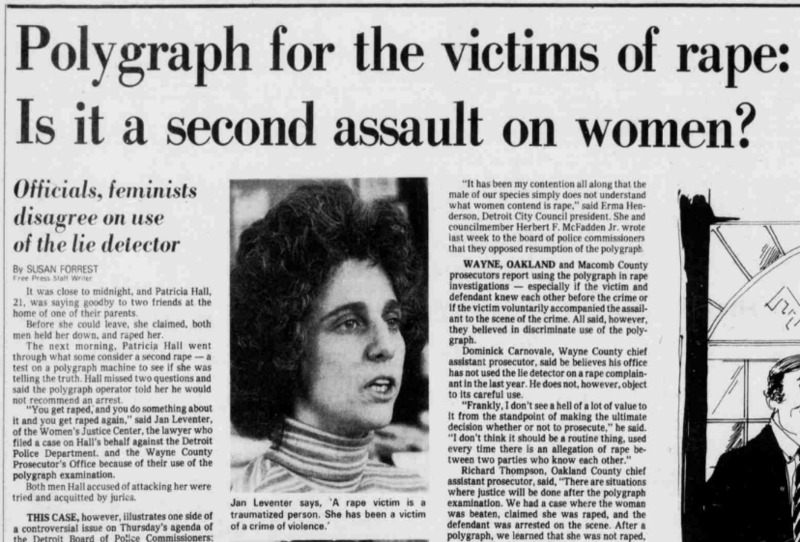

The Sex Crimes Unit underwent crucial changes during the 1970s. The DPD operated under blatantly sexist protocol for dealing with female victims of sex crimes throughout the decade, and many of its policies had the propensity to retraumatize victims. As late as the early years of 1980s, the DPD Sex Crimes Unit Rape Counseling Center in the DPD conducted lie detector tests on sexual assault victims. Concerned citizens spoke out against this policy. In a 1980 letter to the Board of Police Commissioners, a member of the Minority Rape Task Force and a former counselor at the Detroit Rape Counseling Center called for an end to this practice. She pointed to myths about rape that were reinforced by the act of administering lie detector tests, such as that women lie to get revenge or that women are unreliable. For female victims, the lie detector policy also jeopardized faith in the police and the criminal justice system to do right by victims. Policies like these undoubtedly discouraged women from reporting sexual assaults out of fear that they would not be believed, widening the gap between the number of rapes that occur and those reported.

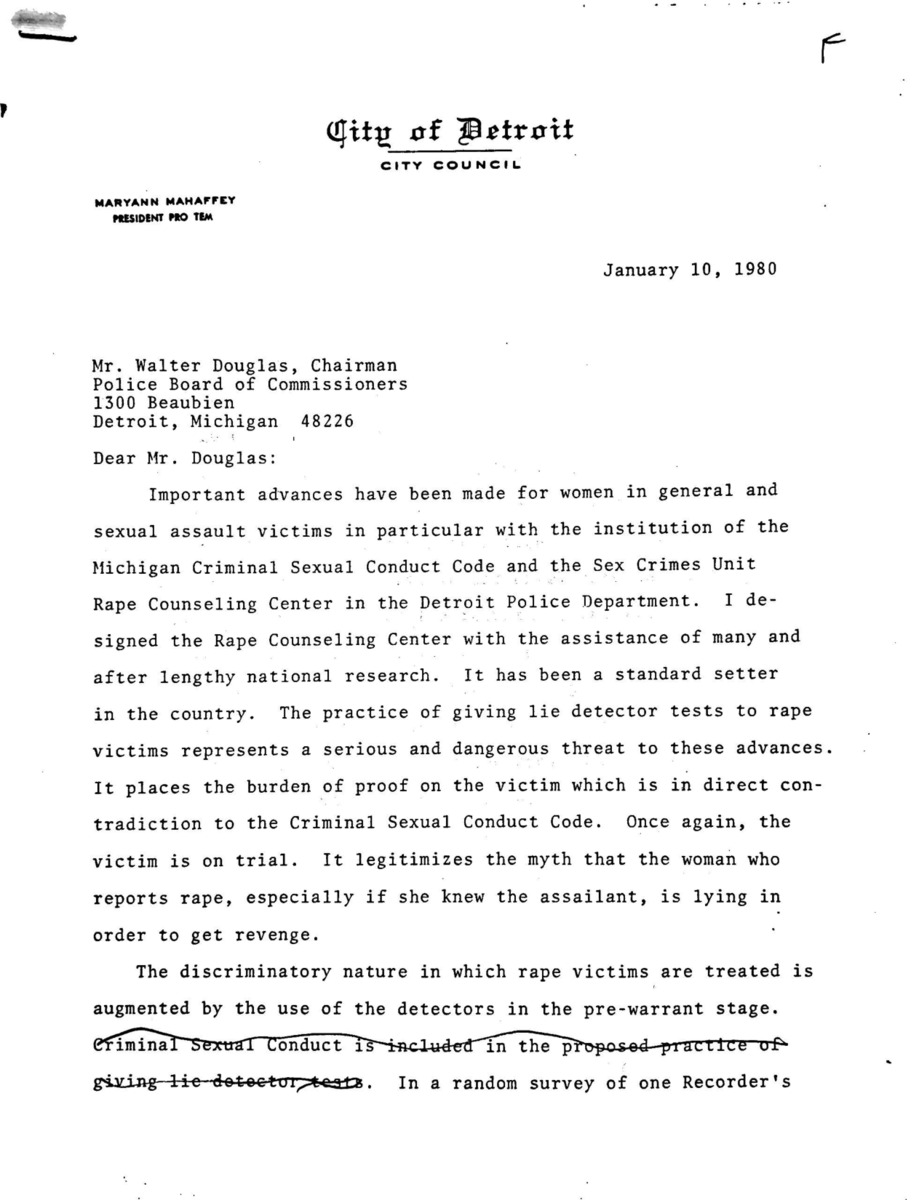

Councilwoman Maryann Mahaffey spoke out against giving lie detector tests to sexual assault victims, as well. Mahaffey called out the double-standard in giving these tests in sexual assault cases but not in other “one-on-one” crimes. She pointed out that in Detroit, sexual assault victims are overwhelmingly Black women. In this way, the DPD policy openly discriminated based on race and gender. Mahaffey believed that the relationship between a victim and “legal personnel” was hindered by the implicit assumption that a victim’s credibility should be tested by a machine. She called for the strengthening of relationships between police, social workers, district attorneys, doctors, and judges, and argues that rather than relying on biased lie detector tests for evidence, police departments should focus on medical evidence kits (rape kits).

Opponents of the DPD’s lie detector policy proposed that cracking down on repeat offenders was the best way to address the problem of sexual assault in the city. In 1978, the DPD established the Special Assault Squad within the SCU, a group of 11 investigators from various departments, including Armed Robbery and Homicide. According to Officer Kelley, the head of the Crimes Against Persons section, “officers became concerned about the growing number of sexual assaults that involved another felony, such as robbery.” However, it is important to note that this squad was chiefly concerned with policing stranger sexual assault, not domestic assault or sexual violence in cases where the victim and perpetrator knew each other.

Another change to the department’s sexist protocol came with the appointment of Ike McKinnon as head of the Sex Crimes Unit.

I was looking forward to my new assignment as lieutenant in charge of the Sex Crime Unit, but didn’t anticipate how depressing it could be at the same time. The first thing I saw as I stepped off the elevator on the seventh floor of police headquarters was a row of wooden chairs lining the hall. The was where the rape victims would sit, right out in public, hurt and demoralized, becoming further victimized just knowing that every person who walked by knew what had happened to them. It disturbed me greatly that they had no privacy and no way to maintain their dignity… Some nights there might be four or five rape victims sitting in the hall with two or three suspects being interviewed at different desks around the room, all out in the open. (Stand Tall, pg.99)

McKinnon soon decided to do something about this. He took it upon himself to create an enclosed waiting area for victims away from prying eyes, a change not universally well-received within the unit: “They thought I was crazy.”

Hear McKinnon describe the changes he made to the Sex Crimes Unit (9:35-11:12):

SOURCES:

Forrest, Susan, "Polygraphs for the victims of rape: Is it a second assault on women?", Detroit Free Press, January 10, 1980

Flannigan, Brian, “Special Detail Cracks Down On Sex Violators!” Michigan Chronicle, August 5, 1978

Interview of Isaiah "Ike" McKinnon by HistoryLab Team, Ann Arbor, MI, Dec. 3, 2019,

https://lsa-dss.mivideo.it.umich.edu/media/t/1_rxtil0md/145739741

Mahaffey, Maryann, Letter to Police Board of Commissioners About Lie Detector Policy, (January 10, 1980), Box 39, Folder 11, Maryann Mahaffey Papers, Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library

McKinnon, Isaiaih “Ike”, Stand Tall, 2001, Sleeping Bear Press

Roberts, Leslie, Letter Objecting to Lie Detector Policy, (January 11, 1980), Box 39, Folder 11, Maryann Mahaffey Papers, Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library

Women’s and Children’s Service Section, “Rape: A Brief Profile,” DPD Annual Report 1974, NCJRS