IN FOCUS: Carl Fitzpatrick

On February 7, 1961, Carl Fitzpatrick told of his personal encounter with the DPD’s unjust crash program. Fitzpatrick, a 31-year old African American man from Detroit, gave a detailed affidavit to civil rights investigators. He described being arrested by the police for reasons he did not know, illegally held for days in the police station, and then criminally and brutally tortured with physical abuse and Russian Roulette. He also lost his job while in detention. While his hand-written affidavit is at times hard to decipher, it clearly recounts the illegal actions of the Detroit Police Department under crash.

Fitzpatrick explained that he had been arrested before and had received a two-year prison sentence back in 1947, as a 16-year-old, for burglary. He served three more years for a very minor parole violation. He received another prison sentence in 1953 for being in the wrong place at the wrong time and charged with accessory to car theft. From then on, he had "been stopped occasionally . . . by the police and required to show my identification." He went to jail again in 1959 on an unjustified public disorder charge from an undercover cop. It is clear from the affidavit that by 1960, Fitzpatrick had faced repeated police harassment, and excessive sentences from prosecutors and judges, as continued punishment for the only offense that he admitted, burglary as a juvenile. He was a marked black man with a criminal record, known to the DPD, and it was about to get much worse.

Nothing prepared Fitzpatrick for the treatment he received in December 1960. On a Saturday morning, he was arrested at his home at 8:30 a.m. by a uniformed police officer. Without explanation, the police took him to the downtown DPD headquarters to be interrogated by the Homicide Bureau. Fitzpatrick had to wait in a room with two hundred other African American men, who also appeared to be arrested for no apparent reason. (It is clear from the context that the DPD picked Fitzpatrick up after the Marilyn Lou Donohue murder as part of a mass round-up of black men in their twenties and thirties who had criminal records, before the much more indiscriminate street sweeps that followed the second Betty James murder).

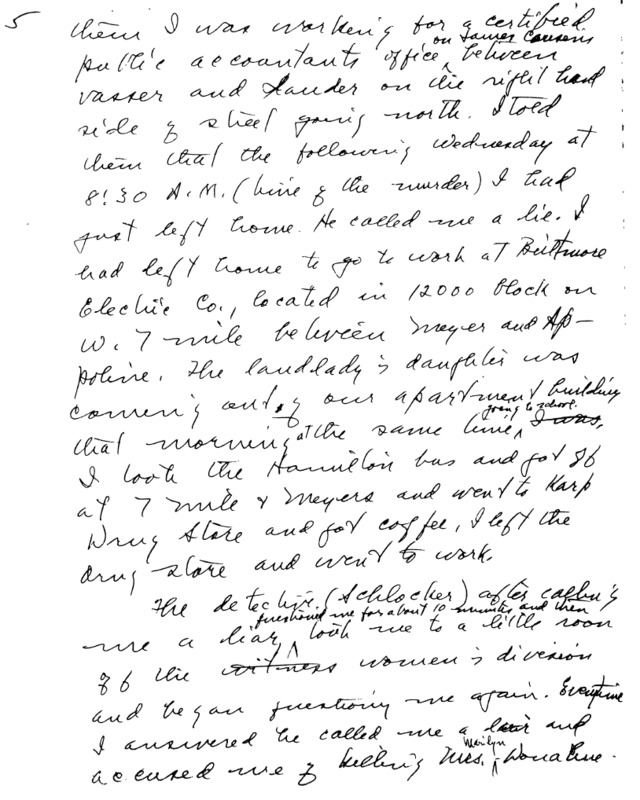

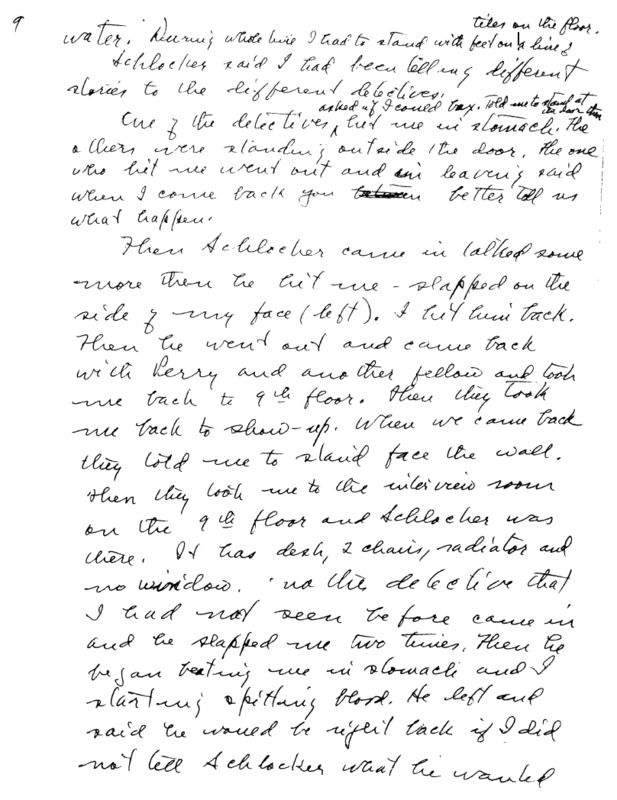

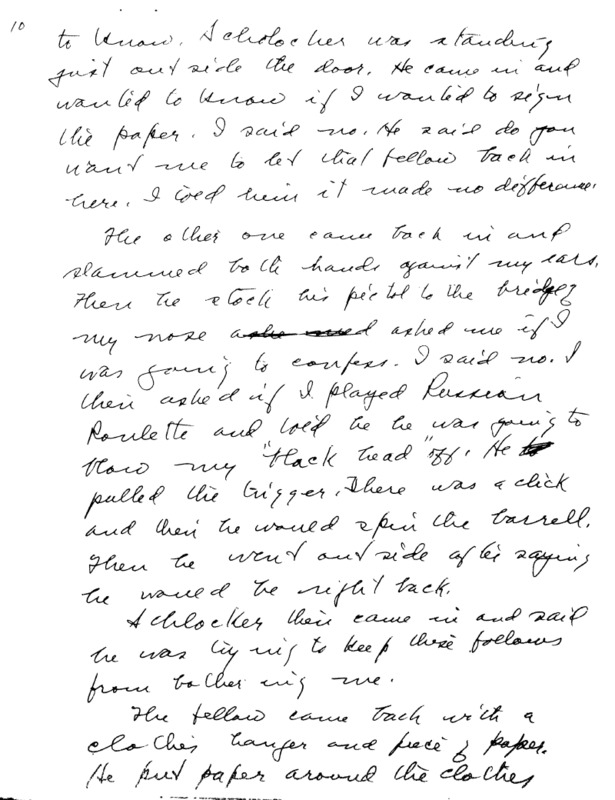

The DPD detectives and officers took Fitzpatrick into various rooms on different floors. They accused him of killing Marilyn Lou Donohue, the first of the two white women murdered in December 1960. He gave his alibi and said he didn't know anything about it. The detectives called him a liar and refuted everything he said. They forced Fitzpatrick to strip off his clothing and refused to allow him to call his landlord, his wife or, most important, a lawyer. They wrote a confession statement and tried to force Fitzpatrick to sign it. They kept him overnight and gave him no food, no water, and no chance to sleep. One detective claimed Fitzpatrick told different stories to different officers. The officers were doing everything to try to get Fitzpatrick to confess to the unsolved murder. They even tried to hypnotize him with a candle, and then there was the physical abuse.

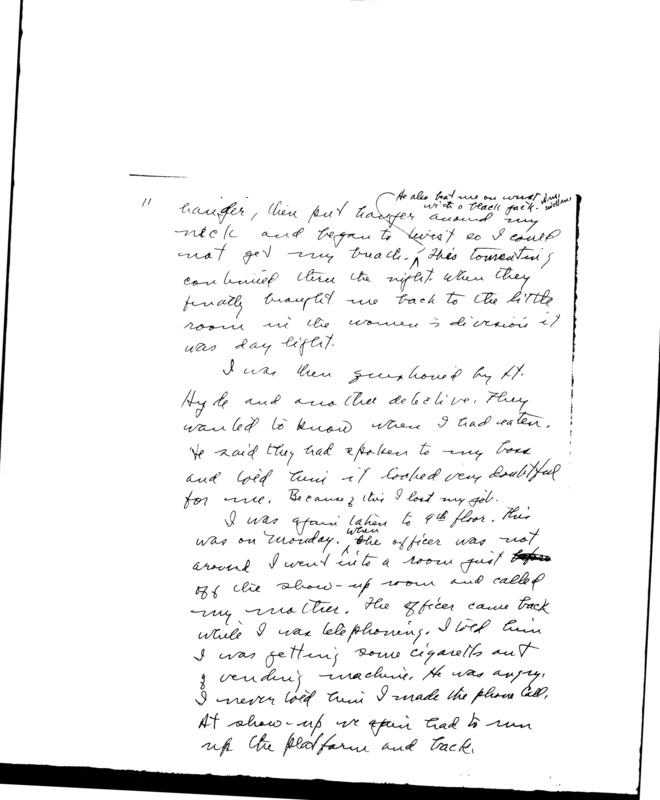

The officers took turns brutalizing and torturing Fitzpatrick. They punched him in the stomach and slapped him across the face. One choked him with a clothes hanger, wrapped in paper so it would not leave a mark, until he could barely breathe. Another beat him with a black jack.

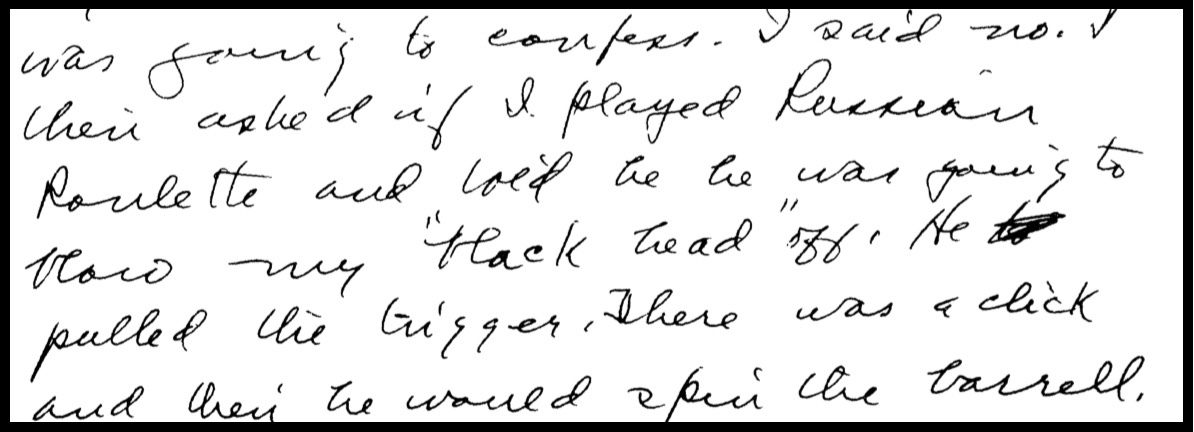

The affidavit ends with a vivid description of the officers torturing Fitzpatrick with Russian Roulette. Fitzpatrick said one officer put "his pistol to the bridge of my nose." The officer said he was going to "blow my black head off." Fitzpatrick tells how the officer "pulled the trigger. There was a click and then he would open the barrel."

After a few days, Fitzpatrick managed to call an attorney, who forced the DPD to release him with a writ of habeas corpus from a judge. The Homicide Bureau did not apologize for the inconvenience, acknowledge the illegal confinement, or address the criminal acts of torture. But one detective did give Fitzpatrick his card and told him if another police officer stopped him in the murder investigation, the detective "would let them know I had been checked."

This final line is confirmation that there were no grounds at all for "suspicion" of Carl Fitzpatrick, beyond his race and gender as an African American man. If his story is representative of those arrested, and there is no reason to think that it is not, then DPD officers were systematically torturing large numbers of black men to see if they could find someone who would confess to the murders of white women that they were under extreme public and media pressure to solve.

There are few records in the historical archive about the experiences of the 1,500 African American men rounded up in the crash program. But Fitzpatrick’s story is undoubtedly just one of many examples of illegal investigative arrest, criminal torture of a prisoner, and other egregious acts by the DPD during the crash program and crime crackdown of December 1960 and January 1961. It took considerable courage for Carl Fitzpatrick to give this affidavit to civil rights investigators, because of the real possibility of police reprisals had it become public. But nothing happened as a result of his affidavit, which was for decades buried deep in the investigative files of the U.S. Civil Rights Commission at the National Archives.

Read excerpts from Carl Fitzpatrick's affidavit below and the full affidavit above right.

Source:

Affidavit of Carl Fitzpatrick, February 7, 1961,18-30, Folder 103963-002-0504, Assault and Abuse of African Americans by the Detroit, Michigan, Police, 1960-1962, Civil Rights Movement and the Federal Government: Records of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, Police-Community Relations in Urban Areas, 1954-1966, National Archives and Records Administration