Police-Community Relations

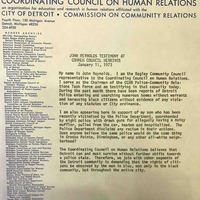

“The degree of hate that exists in the police department is at an all time high, as is the hate in the community for the police. People have not come to hate the police for no reason.” -- John Reynolds, Chairman, Police-Community Relations Task Force, 1973

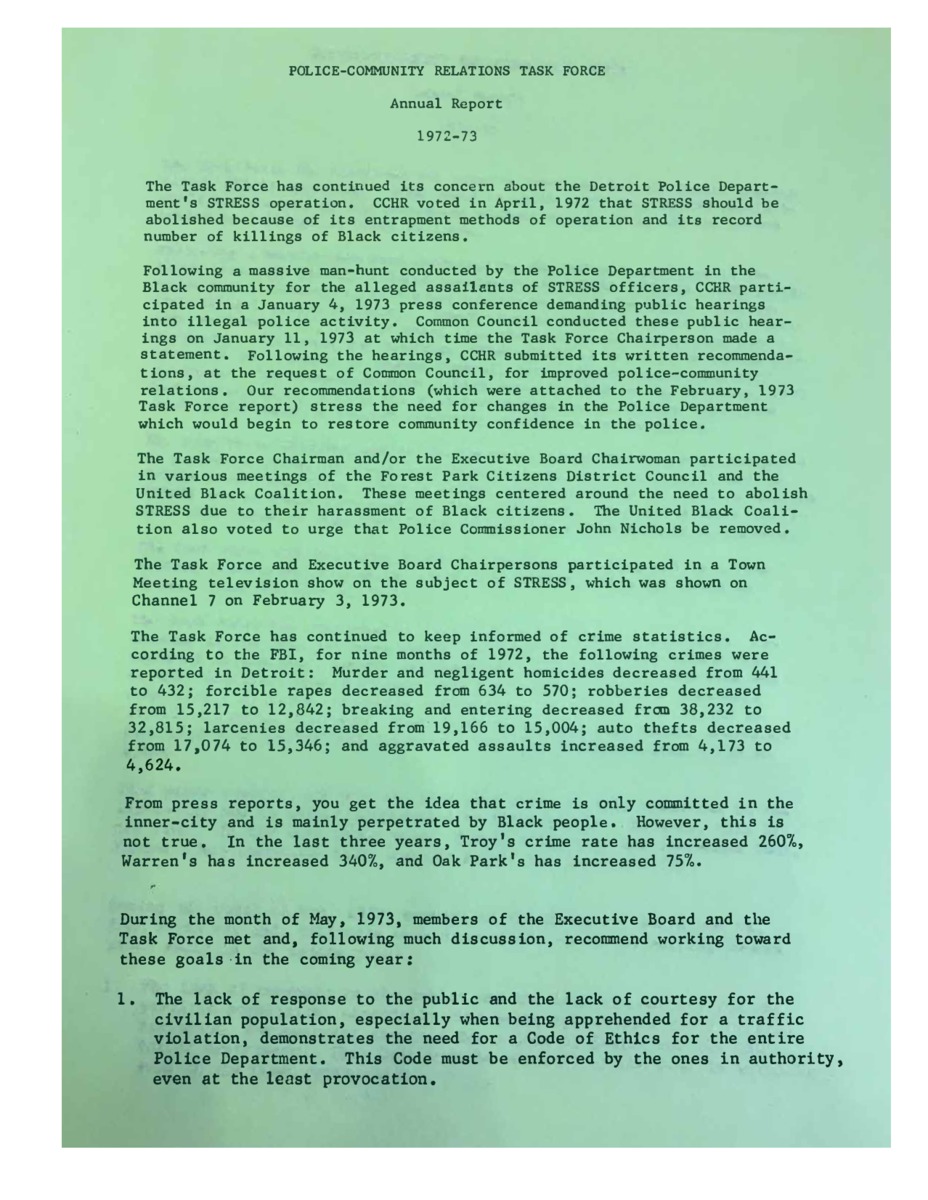

Tensions between police and the larger Detroit community were high in the years following the uprising of 1967. In the Police-Community Relations Task Force Annual Report of 1971, it was reported that “there [was] a great deal more to be done” in terms of strengthening those relations. The 1972 annual report was concluded with a paragraph about the hatred and prejudice that existed within the police department against the communities that they were expected to serve and protect.

The FBI had been surveilling leftist organizations since the 1960s as a part of COINTELPRO, and state police agencies followed suit. Moving into the 70s, White Flight was on the rise in Detroit and throughout the United States, and the country’s greatest perceived threats were street criminals and radical organizers. At this time, perceived criminality and leftist agendas were most threatening to the security felt by white communities. Radical groups were mobilizing, and drug use was more widespread.

Nationwide, criminalization and heavy policing were used to placate the public, and law enforcement agencies around the country--including the Detroit Police Department--followed suit, amping up law enforcement presence, and attempting to deter people from committing robberies, muggings, and minor drug deals by doling out harsh penalties.

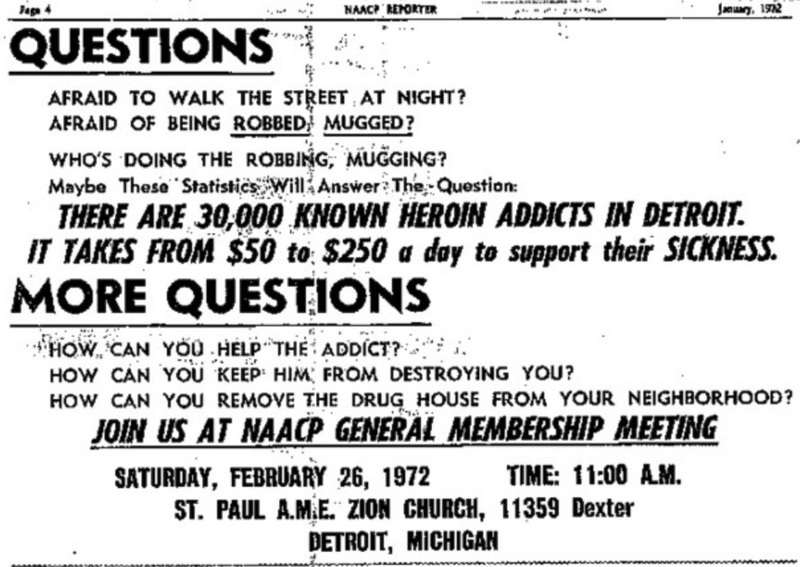

The war on drugs continued to intensify, and the African American community especially was criminalized. Even within that community, the drug epidemic and reported high crime rates had instilled fear. Into the early 1970s, many African American organizations pushed for harsher penalties for drug use and street crimes.

Community Response to DPD's Controversial Tactics

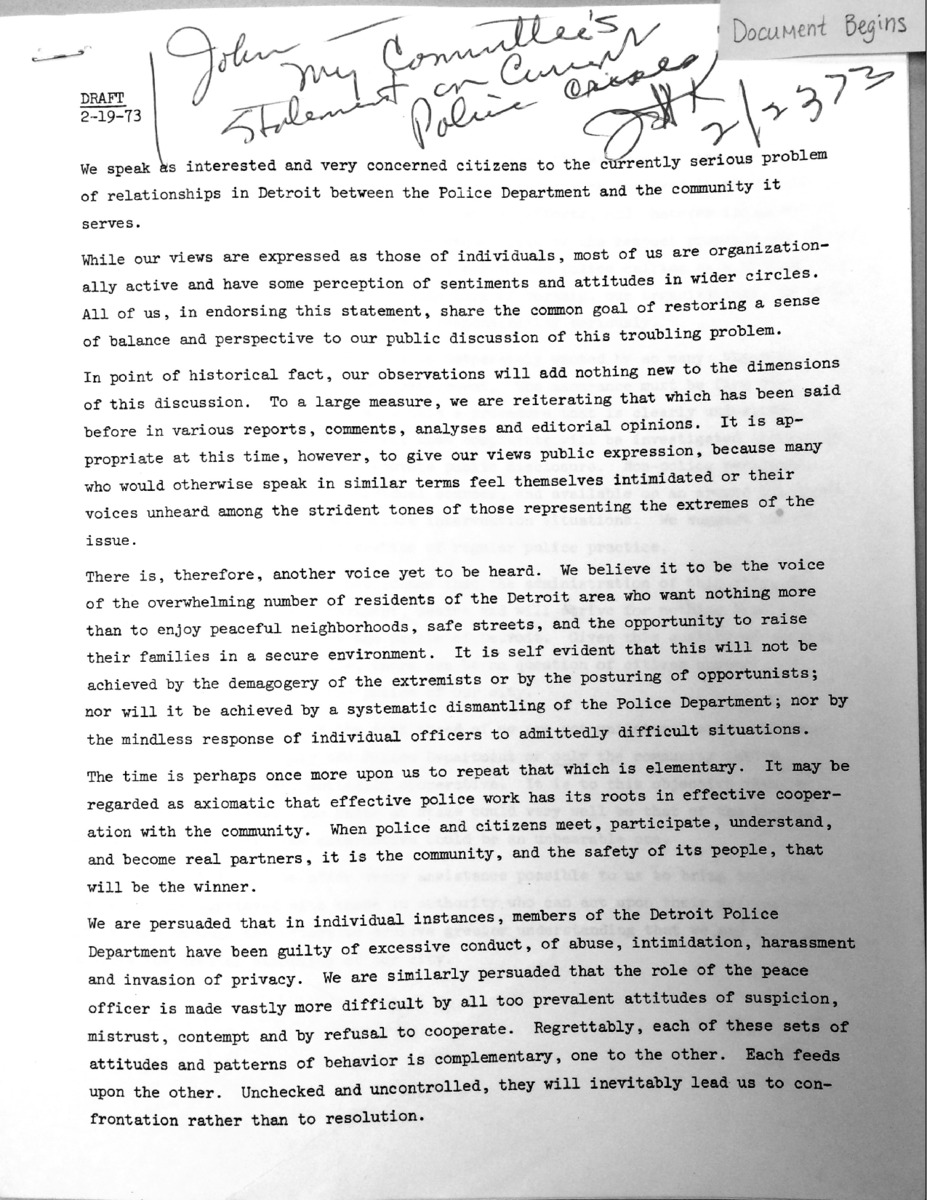

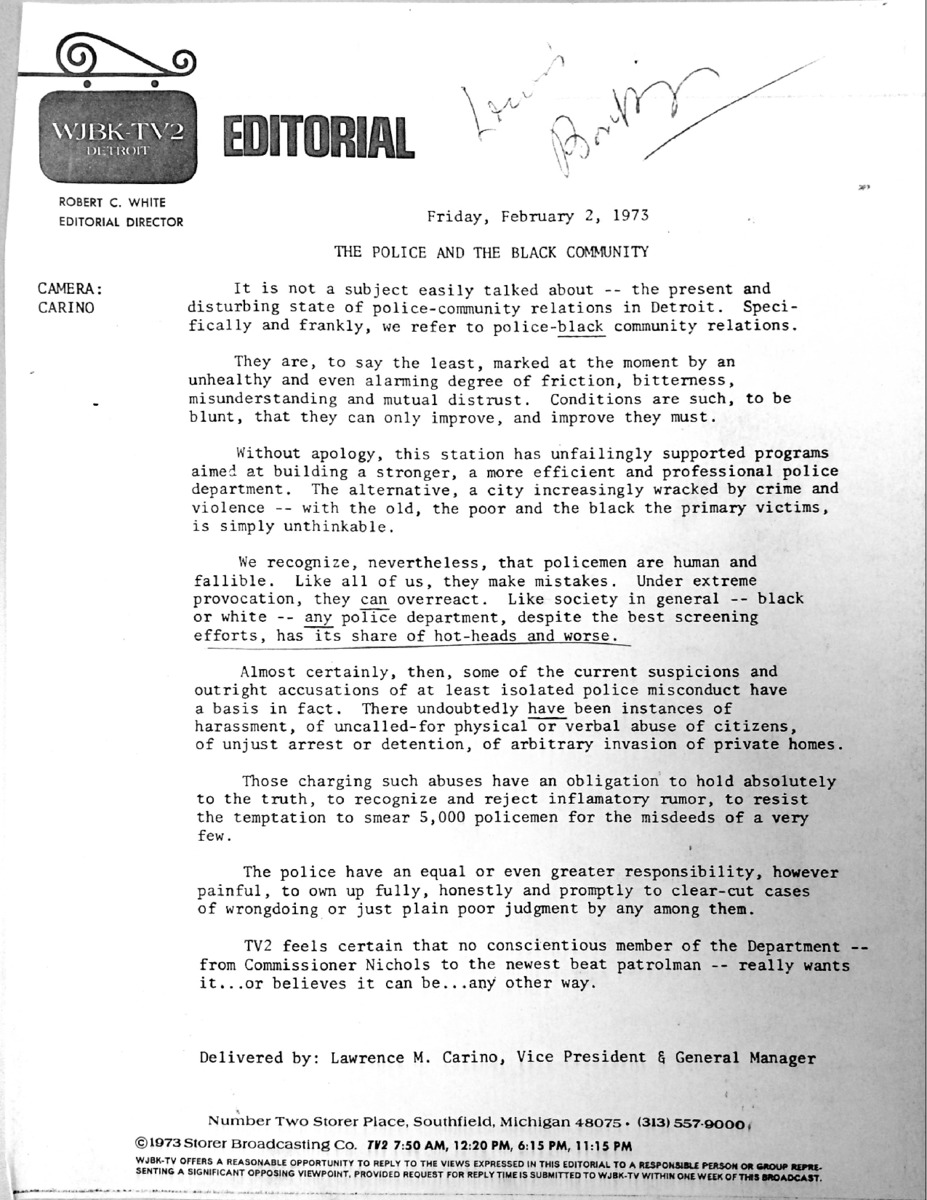

In the same year that the Task Force reported that hate and prejudice were behind the community's distrust for police, WJBK Detroit released an editorial on police-Black community relations, saying that "black or white -- any police department, despite the best screening efforts, has its share of hot-heads" that can make mistakes and overreact. In many ways, along racial and class lines, the city was divided on the issue of crime and policing. Some wanted stricter enforcement of laws, and some wanted reform. Some felt the entire policing and criminal justice system was broken, while others insisted that the major problem faced by police was "bad seed" officers.

While radical organizations seeking to abolish the police or reconceptualize policing as a whole had existed for years, most organizations in the city of Detroit in the early 70s were moderate. Prominent Black-led groups like the Detroit Urban League or the NAACP did feel that crime needed to be cracked-down on, and that only minor changes needed to be made to improve the larger Detroit community. The stances of even these more moderate groups would shift, though, moving further into the 70s.

At the turn of the decade, liberal policies continued to give way to racialized and violent policing practices in the streets, but failed to satisfactorily bring up arrest rates and stop the drug and petty crime problem that the city was facing. Crime rates were continuing to go up, along with statistics about drug use. Part of the city’s inability to solve these problems with heavier police activity was due to DPD officers themselves being involved in criminal activity.

Sources:

NAACP Papers, Library of Congress, ProQuest History Vault

Detroit Commission on Community Relations/Human Rights Department Records, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Detroit Urban League, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

Police Brutality and Misconduct

(decide what goes here and what in coverups)

Gallery below has items

Additional brutality to add

John Reynolds son beaten