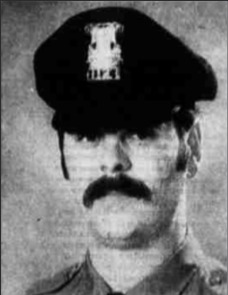

IN-FOCUS: Officer Pongracz

Steven Pongracz was an officer of the Detroit Police Department who was active for 16 years from 1972 until his retirement in 1988. He was a security guard at Great Lakes steel before becoming a police officer with the DPD in late 1971. He began his career in the 5th Precinct station (Jefferson) and transferred to the 4th Precinct (Fort-Green) in 1979 and then to the 13th Precinct (Woodward) in 1985. He retired in 1988 and received a stress-related disability pension.

During Pongracz's 16 years of service, he was sued at least 17 times by citizens who claimed that they were beaten or assaulted by Pongracz while being arrested. In not one of these cases did prosecutors charge the officers for unnecessary force; as a result, the plaintiffs resorted to the civil courts. In these cases, the odds were decidedly more in favor of the plaintiffs. The City of Detroit spent around $1.4 million in settlements with Pongracz's accusers. Despite the constant recurrence of accusations involving violence and misconduct, the city defended Pongracz in cases which surfaced almost every year from 1974 until 1984. Pongracz defended his actions to the Detroit Free Press in 1990, stating that “the force I used was the necessary force. I’m not saying that they’re all lying, I’m saying the physical force used was the necessary force. Once their force stopped, I stopped.” Injuries that victims suffered included broken teeth, feet, ribs, jaws, and gunshot wounds. Many of the complaints against Pongracz follow a similar trend: an intoxicated Pongracz, disproportionate force, and defenselessness.

Other DPD officers and superiors had shown that they were familiar with Pongracz's reputation despite the police department's position that they had no system for accounting for the sum total of suits and complaints brought against him, and so were unaware of his trend of violent assaults and drunkenness. According to Pongracz, officers would joke about how he seemed to attract such a high volume of lawsuits. An officer who worked with Pongracz later testified against him stated:

The Intoxicated Assault and Arrest of Fannie Tully

Fannie Lou Tully was a 41 year-old woman who lived in Southwestern Detroit, just outside of Mexicantown. She was at home on August 22nd, 1984 at 3:45 a.m. when she heard loud voices coming from her neighbor’s house. This tense exchange was between her neighbor and Officer Steven Pongracz, who appeared to be drunk and stumbling. During the argument, Pongracz spotted Tully on her porch and began to quickly approach her home. According to Tully's affadavit in her subsequent lawsuit, she told Pongraz to step away from her, as she noticed that he reeked of alcohol and was obviously inebriated. After she told him to go away, he forcefully grabbed her by the arm and told her “Bitch, you’re going to jail.” It was then that Pongracz began to arrest Tully, in spite of giving no reason for doing so. Pongracz fastened Tully’s handcuffs so tightly that her wrists began to bleed. After she was already handcuffed, he pulled his pistol out and held it against her head, threatening that to“blow [her] brains out”. He dragged her to the police car and hurled her into the back seat, which caused her head to slam against the car on the way in. Immediately after, Pongracz slammed the door on Tully’s bare foot and caused a fracture in her toes. In other arrests, victims of excessive force allege the same pattern; that is, injuring people while violently tossing them into the back of the squad car.

Pongracz was not the only officer involved in the abuse and criminalization of Tully. After being searched at the Fort-Green station, she was driven by two unknown police officers to the Detroit Receiving Hospital. The officers chained her to the hospital bed by her left foot and left arm. She remained chained to the bed as she was being treated, until she was taken to a small, isolated room in the hospital where she was imprisoned for six hours. At 1:00 p.m, nine hours after she was arrested, Fannie Tully was taken to a different police station and charged with intefering with a city official in lawful performance of his duties.

Soon after, the charges of inference were dropped. Another police officer, Stanley Polanski, was present during the initial assault on Tully. Subsequently, Tully sued both officers and the City of Detroit for assault, negligence, and the infringement of her civil rights. However, prosecutors did not bring charges against any officer, and the city would settle the case for $75,000.

In her suit against Pongracz and the City of Detroit in 1986, Fanny Lou Tully brought her complaint to the civil court, with excerpts from the court records describing the event below:

Alcohol Abuse on Duty

This was not the first time that Officer Pongracz was accused by victims of brutality while under the influence of alcohol. In 1977, he was accused of assaulting Wright Handy and beating him at the 5th Precinct station, again while intoxicated. During the same year, Pongracz assaulted Johnnie Robinson after the officer was leaving a bar with other officers at 2:00 a.m. Of the fifteen known cases against Pongracz, and with only a fraction of the circumstantial details in those fifteen cases being known, four allege that the officer was drunk. Of these four instances, two occurred in the year 1977, one in 1982, and the last in 1984. The breadth of these accusations of drunkenness offers consideration of the DPD's procedure for dealing with possible alcoholism or alcohol abuse in active police officers. Pongracz's trend of drunkenness while on duty belies the Department's own ordinance on how the department treats the disease of alcoholism and alcohol abuse. In 1977, the DPD issued a General Order providing the Department's stance on alcoholism. The policy was rather lenient, recognizing societal changes which began to treat alcoholism as a disease. The departmental procedures would offer counseling and treatment to officers who were affected by alcoholism. However, the shortcoming of this policy are illustrated by the Department's classification of its priorities. In a numerical ranking, the DPD viewed alcohlism's "interference" in the police force as affecting job performance, the department's image and the officer's health.

While the policy afforded officers deserved job security by recognizing alcoholism and alcohol abuse as a treatable disease, it only recognized alcohlism as "receiving the same careful consideration and offer of treatment that is presently extended to all members having any other illness." Although the DPD accounted for the department's image and the officer's health as being negatively affected by alcoholism, it did not recognize the temperamental effects that alcoholism could have on an officer, and by extension, on the health and safety of civilians. In this way, alcoholism is not any other disease, as evidenced by the detailed violent encounters between civilians and Pongracz while he was under the influence. That these occurrences spanned seven years attests to the shortcomings of the DPD's treatment of alcohlism and alcohol abuse.

The consequence of the DPD's failure to either treat or punish Pongracz was an often violent combination of heavy drinking with civilian confrontations, whether they be on-duty or off-duty. The "us versus them" complex of police departments [see, Police Violence and Misconduct] often presents hostile situations between officers and civilians. In the case of Steven Pongracz, they could have been exacerbated by his heavy drinking. On August 31st, 1982, Pongracz and several off-duty police officers and firemen were drinking heavily at a public park in Southwest Detroit. Since it was after 10:00 p.m, two residents--Eddie Andrews and Joseph Konkador--approached the officers and asked that they quiet down. As Andrews and Konkador walked back to their homes, two other officers with Pongracz fired 21 shots at the residents. Neighbors claimed that the officers fired upon the residents first, and that the latter returned fire. Other officers at the scene claimed that Andrews and Konkador fired first, and that they only defended themselves. However, Pongracz claims he did not fire at all. In spite of the officers’ assertions that the residents had fired first, Konkador called the police to intervene. Upon their arrival, he was beaten and arrested. Pongracz and the other officers were cleared of assault charges, yet Pongracz was suspended without pay for one month after the incident even in light of his claim that he did not fire his service-issued pistol.

Total Lawsuits and Repeated Brutalities

The Law Department and Police Department argued that they did not have a system for compiling and sharing information on the total number of lawsuits against an officer. However, another noticeable trend in Pongracz’s offenses was that the vast majority occurred around midnight or in the early hours of the morning during the entire 10-year period of offenses. Since most occured while on-duty, this suggests that although Pongracz came to be a 16-year veteran of the department, his shifts were the less desirable midnight “graveyard” shifts, which were often relegated to those officers who were not in excellent standing with their superiors. Yet in all of these lawsuits, the City of Detroit defended Pongracz until they had paid out $1.4 million to his accusers in settlements. Pongracz was not the only officer that the City had spent millions in defense of during this period, with others being:

- Officer Steven Hine, nine cases of $1.1 million in settlement

- Officer Delbert Jennings, seven cases of $86,701 in settlement

- Sgt. Lee Brown, five cases of $1.2 million in settlement.

Included below are the total of known lawsuits against Pongracz, with the total settlement amount spent in his defense by the City of Detroit:

The Victims:

Kenneth Sisk, age 20, was assaulted by Pongracz at 10:30 p.m. on August 27th, 1975 when the officer arrived to pick up friends who had allegedly been tampering with cars. Sisk said that Pongracz knocked him to the ground and kicked him, breaking one of his ribs.

Juan Haygood, age 31, was beaten by Pongracz and an unnamed partner at 3:00 a.m. on January 30th, 1976. The officers arrived to investigate a disturbance in the apartment complex. Haygood said he was attacked when he protested the officers going door-to-door. Pongracz claimed that Haygood shot him in the face with a staple gun, and that he had to “let go” of Haygood’s dog bit him, which caused Haygood to fall down the stairs. By the end of the altercation, Haygood suffered a broken jaw, facial fractures, and broken teeth. Haygood was not charged, and neither was Pongracz.

Theodore Bell was assaulted by Pongracz at 9:25 p.m. on February 16th, 1977 after an argument with his girlfriend. Bell suffered two broken teeth.

Johnnie Robinson was assaulted by Pongracz and other unnamed officers around 2:00 a.m. on May 29th, 1977 while they were leaving a bar.

Leonard Harris, age 25, and John Lee Candate, age 27, said Pongracz and another officer assaulted them on the east side around 1:50 a.m on July 16th, 1977 when they were responding to a hit-and-run incident in the vicinity. The officers said they observed Candate give a shotgun to Harris, who then ran inside his house. Both men said they were attacked without reason, and were outside arguing with neighbors over a parking space. Harris suffered cuts to his head.

Wright Handy said he was assaulted by Pongracz around 11:15 a.m. on September 2nd, 1977. Pongracz and his partner pulled Handy off of a city bus for allegedly drinking and acting debauched. Handy said Pongracz beat him repeatedly while he was held at the 5th Precinct station. He spent six weeks at the hospital recovering from his injuries. Ultimately, Handy was charged with disorderly conduct and Pongracz was cleared of misconduct.

Curtis and Nathaniel Penick, ages 25 and 21, were assaulted on the southwest side at 12:45 a.m. on May 11th, 1982 as they attempted to cross a schoolyard. They were arrested and beaten by Pongracz and another unnamed officer for breaking and entering. The officers claimed that the Penick brothers were drinking on the roof of the school. Curtis was hospitalized for broken ribs and a cut lip. They were acquitted on the breaking and entering charge.

Michael Hagen, 20, was attacked by Pongracz and another officer after he was awoken in his bedroom on May 20th, 1982. While he was being handcuffed, Pongracz placed his knee against his jaw, breaking it and causing his mouth to be wired shut for six weeks. The officers claimed that they chased Hagen on the suspicion of a business burglary, but the charge against him was dropped the next day.

Edward Andrews, age 28, and Joseph Kondakor, age 34, claimed they were attacked around 10 p.m. on August 24th, 1982 by Pongracz and other officers who were drinking in a park. After they asked the intoxicated officers to quiet down, the police opened fire on the pair. Andrews returned fire, but was shot in the arm as he fled to his home. Both parties claim that the other fired the first shots, but Andrews called the police to intervene. Upon their arrival, he was beaten and arrested.

Ernesto Benitez, Rudolfo Moreno, and Wilbert Roberts were arrested on August 5th, 1983 for a concealed weapons charge which they claimed was falsified. Police said they saw the men throw a pistol out of the open rear window, but that rear window was later found to be broken and could not have been rolled down. The men were cleared of all charges, but sued the six officers involved. Pongracz was sued along with the officers because he drove them back to the station.

David Daniel Glenn, age 20, said Pongracz and a partner assaulted him around 4:45 a.m. on February 6, 1984 at an apartment complex while the officers were investigating a domestic dispute. Witnesses said that Glenn told Pongracz that the officers were in the wrong apartment, to which Pongracz told Glenn to “butt out.” After Glenn asked for his badge number, Pongracz took him into the hallway and hit him. Pongracz claimed that Glenn jumped on him to prevent him from arresting another tenant in the apartment complex, but Glenn was acquitted of interfering with a police officer, as was Pongracz cleared of misconduct by the police department.

Fannie Lou Tully, age 41, was arrested and assaulted by Officer Pongracz while he was intoxicated at her home and at the 4th Precinct station on August 22nd, 1984. She was handcuffed so tightly that her wrists bled, had the squad car door slammed on her bare foot to fracture it, and was stomped on by Pongracz at the 4th Precinct station.

Ronald Kinder, age 21, said he was assaulted by Pongracz at 3:30 a.m. on August 25th, 1984, when the officer observed him cutting across a parking lot while walking to his home. When Pongracz asked for his identification, Kinder protested. Then, Pongracz repeatedly slammed his head against a wall and punched him in the face before leaving him. Kinder’s injuries included a gashed eye and broken front teeth. Pongracz was cleared of misconduct.

Dennis Mendoza, age 36, said Pongracz assaulted him after he broke into a bar at 3:00 a.m. on August 29th, 1984. Mendoza was being held by the bar owner until Pongracz and a partner arrived. Mendoza said the officers beat him with a crowbar, rammed his head against the squad car, and then slammed the door on his legs. Mendoza said that he did not resist arrest. When he was brought to the precinct station, he was beaten again. Mendoza received medical attention at a hospital for a ruptured spleen which doctors had to remove. The officers were found guilty by a jury, but a settlement was reached after appeal. Mendoza was also found guilty for breaking and entering and sentenced to 3 to 5 years in prison.

Nickey Hartley of Taylor Pongracz and three other officers awakened him at 4:00 a.m. in his home on November 17th, 1984. They dragged him out of bed by his hair and Pongracz beat him with a flashlight. He said that Pongracz threw him into his bedroom door and then tossed him through a window in his kitchen, shattering the window. Pongracz grabbed him again and pulled him back through the broken window and the officers continued to beat him. He said that even after he was handcuffed they continued to beat him. Hartley was completely naked during the entire incident and was beaten in front of friends and acquaintances.

Silences in Consistencies in Accounts of Police Brutality

The silences and inconsistencies in accounts of police violence become more important when they are vulnerable to manipulation. Since police officers often have an institutional instinct to protect their own, it is incumbent upon observers to more stringently scrutinize the version of events that may have been subject to the “blue code of silence.” [See, the "Blue Code of Silence"]. Officer Pongracz was not charged or convicted of any misconduct in these instances. In the assault of Fannie Tully, up to six different officers were in contact with her both during and after the assault in which she sustained her injuried; yet, none of them testified. Why did only two of the drunken officers in the park fire on the neighborhood residents when they claimed to have been fired upon first, and if Pongracz did not fire a shot, why was he the one who was placed on unpaid leave for 30 days? Even more important is the City’s motivation to defend Pongracz and other officers in 16 cases of recurring brutality when there was no statutory imperative to do so.