Youth Curfew Regulations and Devil's Night

Youth Curfew Regulations and Devil's Night

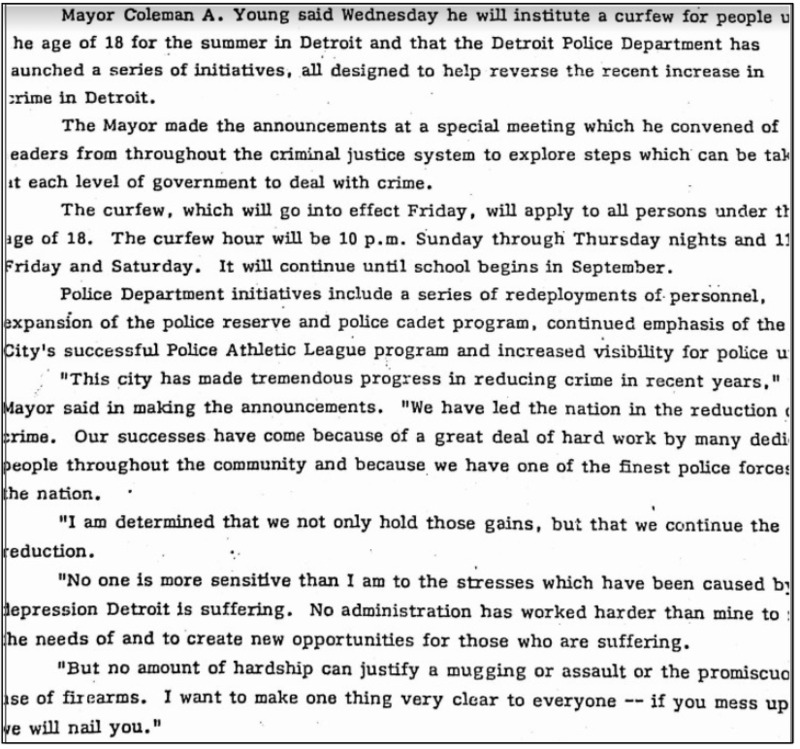

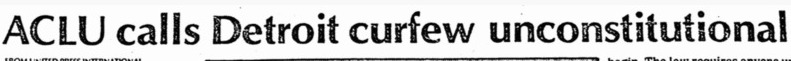

Coleman Young's Curfew OrdinanceIn 1983, Mayor Coleman Young implemented juvenile curfew regulations in an attempt to reduce youth crime and gang activities. The new curfew ordinance required minors under the age of 18 to be off the streets from 10:00pm to 6:00am on weekdays and from 11:00pm to 7:00am on the weekends, with the goal of minimizing crime rates. Young's administration made it clear that no mistakes would be tolerated in his release that stated "if you mess up, we will nail you." This shows the focus on harming the black community, not helping it. The Young administration justified the curfew policy by alleging a significant escalation in youth crime, but statistical evidence (shown below) raises doubt about this claim. This curfew was also vastly different from the 1976 emergency curfews that were put in place because these were long lasting curfews that more directly and explicitly impacted the black community in Detroit. The American Civil Liberties Union denounced Young's curfew policy as unconstutional and argued that the regulations sought to control and repress African American youth by criminalizing them collectively rather than for individual actions. The ACLU portrayed high rates of nonwhite unemployment in Detroit as the main reason behind the youth crime rate and advocated increasing juvenile employment to address the situation. The ACLU also published a question and answer document in response to Coleman Young's curfew that answered commonly asked questions and concerns as well as misunderstandings of the community. Additionally, curfews were a tool used by law enforcement, selectively, and not for all people equally. Blacks were discriminated against significantly during this time, and these curfews were one way of enforcing it.

The ACLU's Curfew Response

The ACLU published an article in the Detroit Free Press in protest to Coleman Young's new curfew regulations. The organization called out these laws as unconstutional and alledged that they were aimed at minority populations with an emphasis on control more than prevention of violence and destruction. The article gives an overview of the impact that the curfews had on the city including a 17 year old high school student who was arrested at a video arcade after his high school graduation with his friends. He was involved with a bigger police sweep of the Greektown area in which over 25 other teenagers were arrested for being out past curfew time for the same reason of being out late after graduation. It was clear through the ACLU report that these teenagers were in the arcade and not causing disruption, violence, or destruction. They also were not approached until after their curfew expired at which time the police arrested them along with the other 25 graduates, all of which were African American teenagers, out past this regulation time. The ACLU also argues in the article that teenagers are not responsible for the increase in crime and violence in the city citing several shootings in Detroit that occurred in the weeks leading up to the implementation of the new curfew ordinance and all who were involved were over the age of 18. This evidence and annecdote shows an alternative reason behind the implementation of the curfews and that it was a systematic method intended to criminalize and control black youth, especially downtown and in particular neighborhoods.

Juvenile Arrest Records: No Wave of Violent Crime

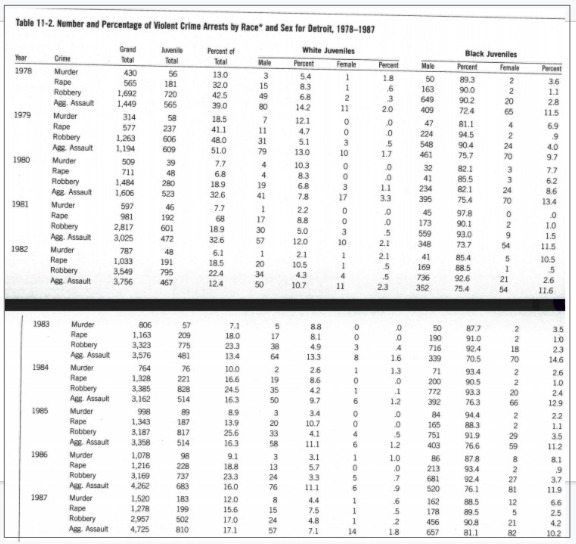

Violent and serious offenses by juveniles did not show a statistically significant increase between the late 1970s and the 1983 implementation of the curfew decree. In fact, while the overall arrest totals for categories including robbery and assault more than doubled during this time period, the juvenile totals were relatively constant and in every year constituted only a small fraction of total crime in the city of Detroit. Law enforcement data reveals 56 arrests of juveniles for homicide in 1978, and 57 arrests in 1983 (7 percent of the citywide total). Juveniles accounted for almost half of all robbery and aggravated assault arrests in 1979, but less than a quarter by 1983. Most of those arrested for violent offenses were male, and African Americans also accounted for an overwhelming percentage of the juvenile totals compared to white youth, but it is important to remember that the city population was around 70 percent black by the mid-1980s due to continued white flight to the suburbs. In 1984, when Coleman Young instituted the first Devil's Night curfew, only about about one-sixth of total arrests in Detroit involved juveniles. Curfews targeted these black youth through discretionary age-based policing, a policy of social control through preemptive criminalization and assumptions of collective guilt.

Devil's Night Detroit - 1984

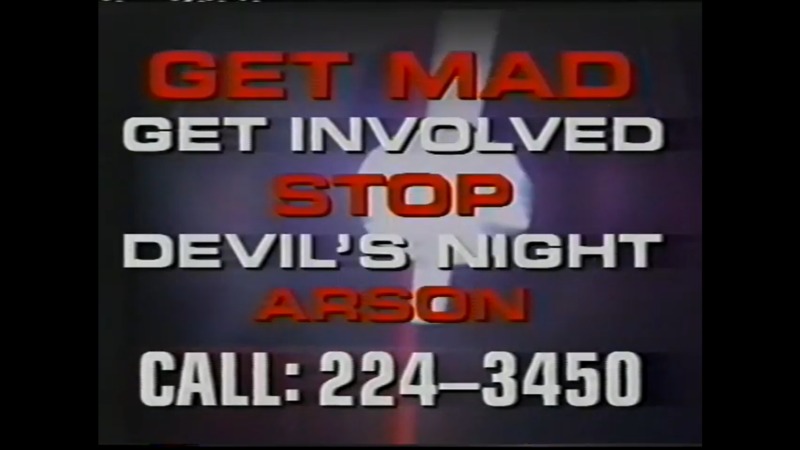

Those familiar with Detroit are undoubtedly familiar with Devil’s Night, a tradition that occurs annually the night before Halloween. Devil’s Night has historically been a night of mischief for Detroit youth. It still exists in a lesser form today, but the Devil’s Nights of the 1970’s and 1980’s were characterized by unparalleled acts of arson. The abandoned properties left over from the stark decrease in population were a prime target, and in 1983 alone there were over 600 fires started. Since Devil’s Night was a night of mischief for youth, they were seen as natural targets for increased security measures.

Although the actions of youth during Devil’s Night were not gang-related, the fear and anger surrounding the event reinforced the characterization of youth as violent, criminal, and dangerous in groups. Devil's Night antics characterized the more common fear among the citizens of Detroit, which was rogue juvenile delinquency exacerbated by underpolicing, a mob mentality, and access to weapons or other dangerous objects.

The 1983 Devil’s Night was especially terrible, and the public was outraged at the loss of wealth and property from the level of vandalism. Therefore, in 1984, Coleman Young instituted the first special curfew intended to control vandalism on Devil’s Night. The mayor announced plans to triple the police presence on the days leading up to October 30th and aggressively enforc the curfew from 10:00 p.m. until 6:00 a.m. Additionally, the city undertook a media campaign to attract volunteers to patrol the city at night and saw great success with thousands of volunteers. The Devil's Night media campaign was one of the largest undertaken by the Coleman Young administration and would continue throughout his tenure.

Community Support for Curfews

Although there were still hundreds of cases of arson in 1984 and vandalism was hardly abated, the Young administration claimed Devil's Night as an astounding success. Although curfews had been instituted in the 1970's in the wake of a surge in youth gangs, the 1984 Devil's Night curfew was beginning of a chain of events and further punitive measures that led to the community's acceptance of the government becoming more liberal with its institution of youth curfews. It is for this reason that Devil's Night can be considered a trial run for youth curfews in Detroit. That summer, Coleman Young reinstituted a curfew for the summer months to popular acclaim. He received widespread support from citizens. Below are reproduced examples of letters of support for the curfew on Devil's Night, undoubtedly showing the political salience of juvenile curfews. Although these are not nearly all of such letters, a tally was found in the archives showing that out of 24 letters sent to the mayor about the curfew during an unknown time period, only 1 letter opposed the curfew. The increased police response to Devil's Night would be viewed retrospectively as one of the premier accomplishments of Coleman Young's mayoral tenure.

Coleman Young's Constituent Correspondence

This form letter was sent out by Coleman Young's office to constituents who wrote in with concerns for their city and their safety. This was found in the Detorit archive along with several folders full of letters, petitions, and notes to the mayor with the cities expression of concern and disgust for the amount of crime that was occurring in the city. This increase in community awareness and distaste for crime in 1984 also shows how ineffective the mayors plans to decrease crime really were. In 1983 when curfews were implemented crime was higher than it was in 1984, and that rates have continued to decrease, however, the types of crime (i.e. crimes committed by juveniles) were decreasing before the implementation of these curfew reguations.

Sources:

“ACLU Calls Detroit Curfew Unconstitutional”. Box 7. Mahaffey Papers, Reuther Library of Wayne State University. 1983.

ACLU of Michigan in Detroit Free Press. Box 7. Mahaffey Papers, Reuther Library of Wayne State University.

Project Youth Survey. Folder 2, Box 653. Millikan Papers. Bentley Historical library, The University of Michigan.

The Coleman A. Young Papers. Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.