Overview

A riot broke out under enigmatic circumstances at a rock concert at Cobo Hall. The audience was far from homogenous—as the rock concert in the downtown area attracted black people from the city and white people who came in from the suburbs. The event devolved into utter chaos because the security and police presence was too minimal to control the crowd. The police framed the violence as instigated by “black youths” and that many were likely part of organized gangs. Witnesses at the scene describe seeing these alleged gang members throwing chairs, rushing the stage, and robbing dozens of people at knife and gunpoint. 47 people were arrested that night for crimes including disorderly conduct, sexual assault, and armed robbery but of those arrested 28 were released that same night without being charged. No one was charged for the gruesome sexaual assaults that were reported by witnesses. DPD reacted to this mass hysteria and outrage about the lack of police intervention at the time by announcing they would be rehiring 450 previously laid off officers, intensifying the restrictions of the city curfew and its enforcement, and increased the number of plain clothed police officers at concert venues and the like (reminiscent of STRESS). This event seems to be a watershed moment in the re-intensification of the police apparatus following Young’s initial reforms earlier in his term. This event typifies a sentiment that seems to have been shared by Young and the leadership in the police department that due process and eradicating crime was far less important than the use of dramatic demonstrations of force and extreme rhetoric to quell public outcry about the perceived crime crisis. Placating the fear of people who read about danger but whose lives were not so directly affected by may have been prioritized over due process for everyone who happened to live in heavily criminal/criminalized communities.

Intensification of Youth Crime Control

In the aftermath of the Cobo Hall Riot the city made a variety of reforms to their approach to juvenile crime. The punitive intensification of the city’s approach to juvenile crime control was certainly not limited to its new emergency curfew order, however, the enforcement of the curfew was an excellent tool to facilitate the other changes.

The police commissioners claim that the new emergency curfew is written in a way that eliminates discretion but that is clearly false. They provide standards for when officers should allow juveniles to continue on their way. Including if they believe they are headed somewhere they can be released to their parent or guardian. But they remain vague enough that officers can simply decide to book or not to book anyone they please.

Before this August, 1976 emergency curfew, any juvenile who violated the curfew would be handled by the Youth Section—a unit of the police department designated to specifically handle youth crime. The new curfew (General Order 76-103) shifts the authority over juvenile curfew violators to the police precincts meaning that teenagers out in public after 10 pm without a parent or guardian were now arrested, taken to the station, fingerprinted, photographed, recorded as violators and then released to their parents. If the teenager is seen committing a first offense misdemeanor—even if it is an aggravated case—can decide to release the offender with a warning.

The design of this policy in terms of the arrest process and the decision to charge or release an offender gave far too much discretion to police officers. This kind of autonomy over who to simply release with a warning and who to arrest and charge with a crime based on no concrete guidelines created a system where officers could treat people based on their own prejudices, regardless of the crime they were accused of committing.

The move to process juvenile curfew violators at the police precinct was—ironically given the arbitrary nature of who was detained and charged—part of a larger effort to increase and systematize records about potential juvenile criminals. While most curfew offenders would be taken to their given precinct anyone suspected of gang activity would be taken directly to the probate court where they would be processed by the Gang Detail—a part of the Headquarters Surveillance Unit. The DPD was aggressively pursuing a way to track gang activity and mass detention based on curfew violations was an extremely helpful tool in this effort. The detention and processing of suspected gang members was not limited to the nighttime hours though.

Following Cobo, Mayor Young requested that the DPD change its policy on identification requests. Before 1975 if an officer asked someone for their ID and they refused—as long as they were not being placed under arrest—they could legally just leave. Now the officer can stop anyone if they decide they have “reasonable cause” and insist that they provide ID. If they refuse or do not have ID the police can arrest them, fingerprint, and process them. The police commissioners even acknowledged that it is common for teenagers not to have ID, which makes this policy very effective at tracking people the police think may be gang members in an official capacity even if they have not committed a crime. This sort of policy is reminiscent of “labeling hype” a phenomenon which historian and ethnographer Victor Rios describes in Los Angeles among black and latino youth who have been arrested and regardless of whether or not they have been convicted of a crime deemed gang members. In both Detroit and Los Angeles the police’s labeling—often incorrectly—of black and latino youth further criminalizes them as they face both concrete ramifications of appearing in a database as a gang member as they try to seek employment and interact with the law in the future. And perhaps to an even more significant degree it criminalizes them by engendering in them the mindset that they are inherently criminal. When one’s government is constantly telling them their very existence is a crime they start to believe it.

Many of these reforms enacted by the Board of Police Commissioners come at the recommendation of outside sources, namely the mayor’s office and a body Mayor Young formed in the immediate aftermath of the Cobo Hall incident called the, Business & Labor Ad Hoc Committee on Crime & Youth. The members of this committee were made up of officials from various sectors of Detroit law enforcement, labor union leaders, and local businesspeople. The Ad Hoc Committee’s recommendations contained a mixture of punitive and rehabilitative proposals.

The essence of the underling argument contained within their recommendations is that the more involvement the city has in the lives of youth the better. They should come down hard on serious juvenile criminals but provide educational alternatives for students who may be at risk of getting caught up in criminal activity but can be deterred.

The Ad Hoc committee advises the city to move the disciplinary responsibility from the Probate Court for youth status offenders—minors who have committed offenses that are not illegal for adults e.g. truancy—charge the Department of Social Services to remedy such problems. They also recommend lowering status offender age to 16 from 17. Furthermore they ask that Probate Court Judges be allowed to send youth to “State training institutions” if the deem it appropriate. It is not mentioned whether they have to have been convicted of a crime but merely that it would “give some alternatives to the juvenile situation we have in the street.” They anticipated this increased sentencing would require an additional 350 spaces in state detention facilities.

The proposals for education based reforms to the juvenile justice system extend into local schools, where the Ad Hoc committee requests that the state provide funding for “mini-schools” where students with disciplinary issues could be diverted outside of the legal system for extra help.

The committee also recommends the state enact mandatory-minimum sentencing guidelines to ensure individuals convicted of the most serious crimes could not receive lenient treatment. The judges would hold on to some discretion but no one convicted of any of the proposed “major felony offenses” would be eligible for parole.

In the abstract these proposals seem well intentioned and just. However, in tandem with the way the city has begun to obsessively track the movements of youth through the curfew and gang task forces these measures only further entrench the government in the lives of kids leading to further criminalization down the road.

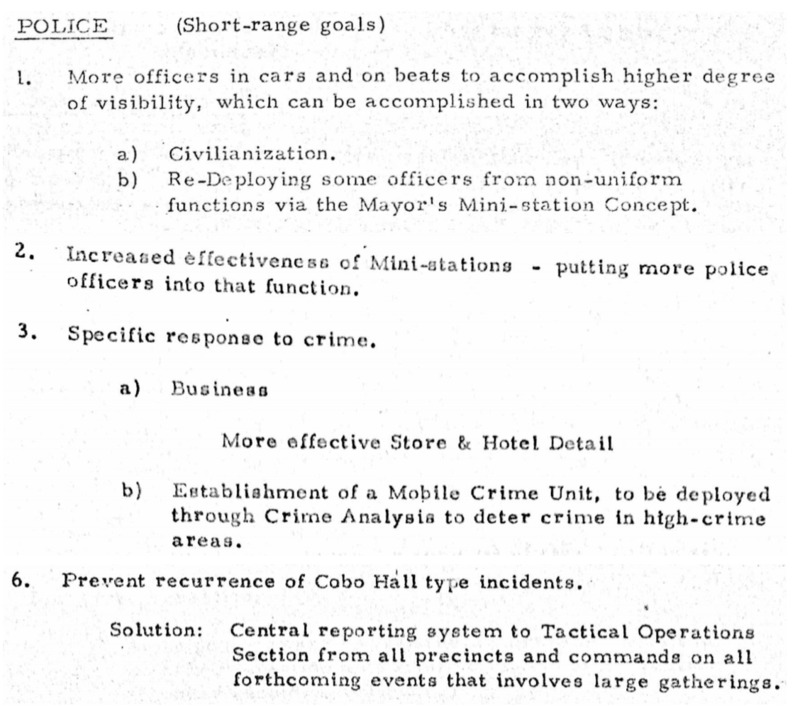

The proposals for reform promulgated by the DPD were in line with the philosophy that police ubiquity and punitive policy would lead to a reduction in crime. The aftermath of the Cobo Incident saw the return of plain clothed police officers and the DPD's support of Young's mini-station program. Young's theory of community policing via mini-stations, just like all of the other ways the government—more specifically law enforcement officials—began to pervade in to private life, the intention of building trust was never going to succeed as the relationship is always inherently adverserial given that one side is simultaneously tasked with establishing control through punitive measures.