4. Wrongful Convictions

The criminal justice system in the United States contains various safeguards designed to prevent innocent people from being convicted of crimes they did not commit. Preventing wrongful convictions was important enough to the nation’s founders that they dedicated three of the ten constitutional amendments in the Bill of Rights to providing protections for people accused of crimes. The Fifth Amendment gives individuals the right not to incriminate themselves and not to be imprisoned without due process; the Sixth Amendment guarantees the right to a speedy public trial by a jury of one's peers as well as the right to legal council; the Eighth Amendment forbids excessive bail, fines, and cruel and unusual punishments.

Despite these safeguards the risk of wrongful conviction remains. The protections afforded to those accused of a crime can only work to the extent that the officials and institutions tasked with providing them actually do so. Even in cases where the rights of the accused are respected, a variety of other factors, including misleading evidence, inadequate police investigations, mistaken witness testimony, false confessions, and false accusations can still result in wrongful conviction and imprisonment. The unavoidable possibility of wrongful conviction makes it all the more important that the police officers, prosecutors, forensic analysts, judges, and public defenders, who collectively make up the criminal justice system make every effort possible to ensure that their work does not put innocent people in jails and prisons.

Wrongful Convictions and Exonerations in Detroit

In Detroit, those in charge of the criminal justice system have not always fulfilled their responsibility to protect the rights of the accused and safeguard against wrongful convictions. Recently, those failures have become more visible. Improvements in forensic science, including DNA testing, have helped many wrongfully convicted individuals prove their innocence and regain their freedom. Relatively new initiatives such as the national Innocence Project, founded in 1992, and the Michigan Innocence Clinic, founded in 2009, have provided legal and investigative assistance to wrongfully convicted people and have helped exonerate many. In 2018 the Wayne County Prosecutor’s Office, led by city prosecutor Kym Worthy, created a Conviction Integrity Unit tasked with reviewing cases of individuals who claim to have been wrongfully convicted. Collectively, these developments have unleashed a torrent of new exonerations in the past twenty years, freeing dozens of innocent people, costing the city of Detroit millions of dollars in restitution payments, and exposing historical patterns of malpractice at various levels of Detroit’s criminal justice system, some of which still appear to be present today.

This map shows the locations of many of the alleged crimes for which Detroiters were wrongfully convicted between 1974 and 1993. Hover over a point to learn more about the exoneration it represents.

Since many of those exonerated in recent years were originally convicted decades prior, their cases can shed light on the state of policing and prosecution in Detroit and Wayne County during the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s, the period explored in the exhibit. Drawing on data from the National Registry of Exonerations, a collaborative project founded in 2012 that seeks to document all known cases of exonerations from 1989 to present, as well as newspaper reports, court records, and other official documents, it is possible to piece together a picture of the pattern of mistakes and misconduct that contributed to the large number of wrongful convictions in Detroit between 1974 and 1993.

Before delving into the details of Detroit’s history of wrongful convictions, it is important to acknowledge the limits of the available data. The wrongful conviction cases explored below all involve individuals who were convicted in Wayne County between 1974 and 1993 and were exonerated after 1989. Thus the data set excludes anyone exonerated prior 1989 and, importantly, any wrongfully convicted individuals who have not yet been legally exonerated.

The exclusive inclusion of cases that resulted in legal exoneration creates biases in this data. For one, the wrongful convictions in this set are more likely to be related to major crimes. Since the appeal process is long and expensive, often lasting over a decade, individuals wrongfully convicted of minor crimes with shorter sentences are much less likely to get full exonerations prior to their release. Although several of the individuals in this data set were exonerated after serving their sentence, it seems reasonable to assume that those with shorter sentences related to less serious criminal allegations would be less likely to go through the intensive effort required to receive legal exoneration. Similarly, this data set is likely biased towards cases with circumstances favorable to meeting the legal requirements for exoneration. Legal standards for overturning a conviction and granting a new trial make it easier for some wrongful convictions to be overturned, while making others more difficult. Inadequate legal defense, for example, may be overrepresented in this data set because courts tend to be willing to overturn convictions when the convict can clearly demonstrate that they did not receive adequate legal counsel. The most blatant forms of official misconduct, such as hiding or tampering with evidence may also be overrepresented. Forms of misconduct that are less likely to leave a paper trail, such as verbal intimidation of witnesses or investigative failures are probably underrepresented. Cases in which an individual made a false confession or in which new evidence was later discovered may also be underrepresented.

Patterns of Wrongful Convictions

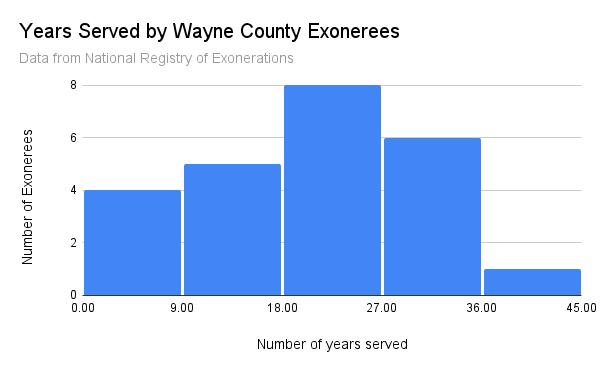

What can we learn by examining this set of wrongful convictions? First and foremost, these cases drive home the tragic human cost that errors and misconduct in the criminal justice system can wreak on citizens. Between 1974 and 1993, at least 24 individuals were wrongfully convicted in Wayne County before later being exonerated. The average time spent wrongfully incarcerated for these exonerees was just over twenty years. Cumulatively, the group members lost 496 years of their lives to wrongful convictions. The extent of that astounding loss and the suffering it entailed is difficult to imagine, but it nevertheless makes it clear that failures in the criminal justice system can produce horrific outcomes for wrongfully convicted individuals as well as their friends and families.

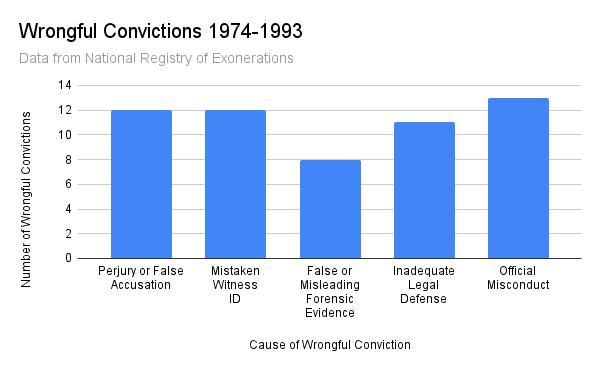

The data on wrongful convictions in Detroit also provides useful information for those concerned with preventing wrongful convictions. By looking at the factors that led to wrongful convictions in these case studies it is possible to identify problematic patterns of mistakes and misconduct among police, prosecutors, public defenders and judges. To facilitate this, contributing factors in this data set have been grouped into five broad categories used by the National Registry of Exonerations. These are: Mistaken Witness ID, False or Misleading Forensic Evidence, Perjury or False Accusation, Inadequate Legal Defense, and Official Misconduct. In the vast majority of cases there were multiple factors that contributed to the initial wrongful conviction.

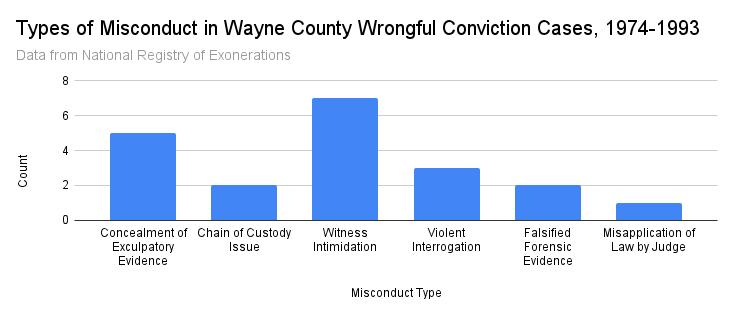

One of the most striking features of this dataset is the frequency of cases involving official misconduct. Among the 24 known wrongful convictions that took place during this exhibit’s time period, 13 involved some element of clear misconduct on the part of criminal justice officials. While the specific details of the misconduct in these cases varied, the vast majority of them (11 out of 13) involved either witness intimidation or the concealment of evidence favorable to the wrongfully convicted defendant. Upon closer examination, many of these cases seem to hint that broader cultural and systemic issues within the Detroit Police Department created an environment where wrongful convictions were more likely to take place. Several of these case studies are explored in more detail below, and elsewhere in this exhibit.

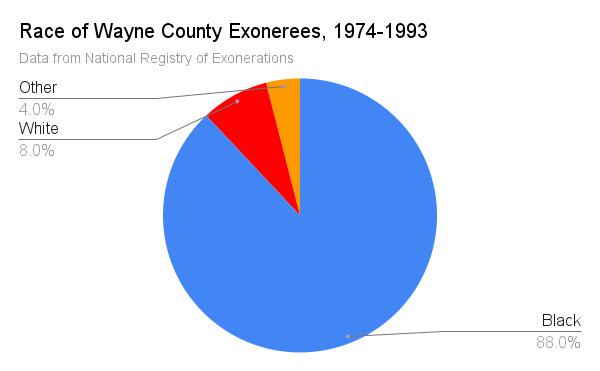

Finally, it is crucial to note that this data affirms a broader trend evident in this digital exhibit and countless other studies of policing and criminal justice in the United States: that African Americans are disproportionately harmed by the problems in our criminal justice system. Eighty-eight percent of exonerees wrongfully convicted in Wayne County between 1974 and 1993 were African-American men. Although Detroit was a Black-majority city throughout much of this time period, with the African-American population ranging from 43% of the total in 1970 to 75% in 1990, at no point did Black residents constitute more than 80% of those living in the city. The disproportionate representation of Black men in the available data on wrongful convictions shows that African Americans were significantly more likely than their white counterparts to be convicted of a crime that they did not commit. The racially disparate impact of wrongful convictions is a central implication of this dataset, and an important context for the systemic issues and patterns of misconduct discussed in greater detail in the following section.

Dwight Love and Ledura Watkins: Miscellaneous Files and the Concealment of Exculpatory Evidence

Before a person accused of a crime in the United States goes to trial, both the defense and prosecution go through a process called discovery, wherein both sides must exchange information about the evidence and witnesses they have collected and plan to present in court. In its 1963 ruling on the case of Brady v. Maryland, the Supreme Court affirmed that the suppression of exculpatory evidence by a prosecution represents a violation of a defendant’s right to due process as guaranteed by the fourteenth amendment. In other words, police and prosecutors are not supposed to hide relevant evidence from a defendant, especially when that evidence is favorable to the defense.

There is some evidence from this set of wrongful conviction cases that suggests members of the homicide unit of the Detroit Police Department routinely and intentionally hid exculpatory evidence in murder investigations, and that the concealment of such evidence may have been standard practice for decades.

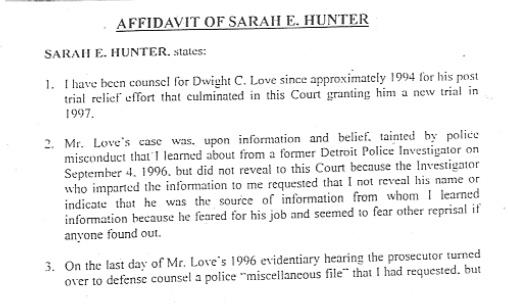

In 1996, attorney Sarah Hunter was working to overturn the life sentence of a man named Dwight Love, who had been wrongfully convicted of murder in 1982. As a part of her investigation into Love’s case, Hunter made contact with a former Detroit police officer named Ritchie Harrison. According to Hunter, Harrison described a systematic pattern of misconduct in the Homicide Department and the Major Crimes Unit of the Detroit Police Department. Harrison alleged that the chief of the Major Crimes Unit at the time, Commander Gerald Stewart, had encouraged him to “learn to lie” and to “have enough detail to back it up." Harrison also reportedly accused Stewart and other officers in the Major Crimes Unit of destroying exculpatory evidence in multiple cases. Finally, Harrison told Hunter that the Homicide Department routinely used files labeled “miscellaneous” as depositories in which they stored any and all evidence that might serve the defense of a suspect that they were seeking a warrant for. Harrison explained that the purpose of these “miscellaneous files” was to hide exculpatory evidence from both prosecutors and defendants. Hunter later testified as to the details of her conversation with Ritchie Harrison in a sworn court affidavit, excerpts of which are reproduced below:

"10. Mr. Harrison told Mr. Robertson and me that Commander Gerald Stewart was a person who resorted to illegal tactics in convicting and framing others by hiding exculpatory evidence and/or that he would destroy evidence. Mr. Harrison stated that he was on leave from his the [sic] department because he had refused to destroy evidence at Stewart’s behest, and he gave us the name of that case and the details of what occurred when he refused to destroy and tamper with evidence, although I did not verify the details of that case.

11. Mr. Harrison said that when he came to work in Commander Stewart’s Unit he was instructed that the first thing he was to do was to learn to lie and he better have enough detail to back it up.

12. Mr. Harrison said that he witnessed Commander Stewart [the Chief of the Major Crimes Unit of the Detroit Police Department] and others shredding and destroying evidence in one case in particular that he named, and in others.

13. Mr. Harrison also told Mr. Robertson and me that Commander Stewart was a person who probably would not care than [sic] an innocent person was wrongfully convicted...

15. Mr. Harrison explained that a “miscellaneous file” is created for every homicide case and that in these files the police pick out every bit of evidence that is exculpatory as to the perpetrator they will seek a warrant for, and every other piece of evidence that is inconsistent with their theory of who did the crime, and they leave it in the miscellaneous file before presenting the case to the prosecutor’s office for a warrant.

16. Mr. Harrison told me and Mr. Robertson that he believed the prosecutors in Wayne County do not know about the miscellaneous file but that there is one for each case, and that very few people knew that such files existed. He said these files are intentionally created by police to conceal exculpatory evidence, even from the prosecutor.

17. Mr. Harrison said that no one knows about the miscellaneous files except for people who work in Homicide, and he gave us the impression that no one else was supposed to know about the miscellaneous file."

Given an absence of additional evidence to verify the statements Harrison made to Sarah Hunter, it is not possible to know if all his allegations about destruction of evidence and other criminal police practices in the Major Crimes Unit were true. One element of Harrison’s story, however, was verified by Sarah Hunter shortly after their meeting.

Armed with knowledge of “miscellaneous files” Hunter asked a court to order the Detroit Police Department to hand over the miscellaneous file in Dwight Love’s case. The court granted Hunter’s request, and by the end of 1996 she had obtained a copy of the file, which had never been given to Love’s original defense attorney. In the file Hunter discovered a trove of exculpatory evidence that would have made Love’s original conviction much less likely, including multiple witness statements pointing to other culprits. At least in Love’s case, Harrison’s allegations about the use of miscellaneous files to hide exculpatory evidence appear to have been true.

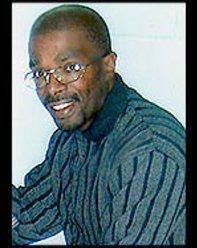

Proof of the suppression of evidence in Love’s original trial by means of a miscellaneous file eventually helped Hunter convince a court to overturn Love’s conviction, however it was not enough on its own. Hunter also showed the court evidence that police had intimidated Love’s then-girlfriend to change her testimony and undermine Love’s alibi and produced a signed confession to the murder made by another man after Love’s conviction. Together these elements met the extremely high standards necessary to secure a new trial. In 2001 prosecutors finally dropped all charges against Love, exonerating him after nearly 20 years. Love had spent 16 of those years wrongfully incarcerated. He missed his mother’s funeral and the birth of his first grandchild while in prison for a crime he did not commit. Love never received a penny in compensation.

Love’s is not the only wrongful conviction in this data set that was caused, in part, by the concealment of exculpatory evidence in a miscellaneous file. In 2009 a man named Ledura Watkins, who had been wrongfully convicted of murder in 1976, obtained the miscellaneous file for the homicide investigation in his case. The file Watkins received contained over 300 pages of evidence that had not been made available to his original defense lawyer. The miscellaneous file included evidence that Travis Herndon, Watkins alleged co-conspirator in the murder and the only witness linking Watkins to the crime, had at one point told police that Watkins had acted alone in carrying out the crime. At Watkins’ trial Herndon changed his story to testify that he had been there when Watkins committed the murderand, in exchange for testifying, a prosecutor granted Herndon immunity from prosecution in connection to the crime. The miscellaneous file also contained evidence about other suspects in the case that would have helped Watkins’ defense in the initial trial.

Just like Dwight Love, Ledura Watkins needed more than the evidence in his miscellaneous file to finally convince a court to overturn his original conviction. Watkins already had one such piece of evidence, as Herndon had recanted his testimony against Watkins years earlier in 1980. Watkins and his lawyers also managed to produce several additional pieces of evidence in his favor, including police forensics reports that had not been handed over to Watkins’ original defense. In 2017, a judge ordered that Watkins' conviction be vacated. Wayne County prosecutors promptly dismissed all charges against Watkins and he was finally released. Watkins had been just twenty years old when he was wrongfully convicted. At the time of his exoneration Watkins was 61 years old, having spent 41 years incarcerated for a crime he did not commit.

Watkins’ case suggests that using miscellaneous files to hide exculpatory evidence in murder cases may have been a long term standard practice for officers and investigators in the Homicide Department in Detroit. The fact that a miscellaneous file was produced in the investigation that led to Watkins’ wrongful conviction shows that such files were being used to conceal evidence as early as 1975. When Dwight Love was wrongfully convicted in 1982, miscellaneous files were evidently still being used to conceal exculpatory information. As late as 1996, when attorney Sarah Hunter first learned of the existence of miscellaneous files, they were allegedly still a ubiquitous feature of investigations in the Homicide Department.

While there is no available evidence that corroborates the full extent of the allegations made by former Detroit police officer Ritchie Harrison to Sarah Hunter in 1996, his description of the use of miscellaneous files by the Homicide Department of the Detroit police appears to have been accurate. Moreover, as evidenced by the cases of Dwight Love and Ladura Watkins, the use of miscellaneous files to hide exculpatory evidence appears to have been common practice for at least twenty-one years between 1975 and 1996. It is impossible to know based on current available information how many murder cases in that twenty year span were seriously compromised by the use of miscellaneous files. It will likely never be possible to know how many people were wrongfully convicted and incarcerated as a result of this practice. What we can conclude from these cases is that for more than twenty years officers and investigators in Detroit’s Homicide Department were willing to violate the rights of the accused in a systematic fashion. The fact that the practice continued for so long is indicative of a police culture in which officers “probably would not care if an innocent person was wrongfully convicted.”

Darrell Siggers and Desmond Ricks: Witness Intimidation and Faulty Forensic Evidence

The available data on wrongful convictions in Wayne County between 1974 and 1993 also shows strong evidence of two other systemic issues: intimidation and coercion of witnesses by police and poor handling of forensic evidence. In at least two exoneration cases in this data set, those of Darrell Siggers and Desmond Ricks, misconduct and mishandling of both witnesses and forensic evidence compounded one another and led to wrongful convictions. Together, these two wrongful convictions represent a callous attitude on the part of police investigators that is fairly representative of wrongful conviction cases in this data set and of the worst elements of police culture in the Detroit Police Department as a whole.

Darrell Siggers spent 34 years wrongfully incarcerated after being wrongfully convicted of first-degree murder in 1984. Sigger’s conviction was based almost entirely on testimony from two witnesses, both of whom admitted to being intoxicated at the time of the shooting and both of whom had been standing a great distance away from the shooter. One of the two witnesses that identified Siggers as the shooter later told a relative that he had only identified Siggers after police had threatened to have him arrested for the crime. Two additional witnesses who later came forward reported that they had told police that another man had committed the crime but that police at the time had similarly threatened them with arrest unless they agreed to withhold their statements. Siggers and his attorneys used these statements to challenge his conviction and request that he be granted a new trial. In 2004, however, a judge denied Siggers’ motion, arguing that the three statements about police intimidation of witnesses were not sufficiently credible. Siggers would need more evidence if he was to escape his wrongful incarceration.

Four years later, in 2008, an external event pointed Siggers in the direction of the evidence that would ultimately compel a judge to vacate his conviction. A private investigator for a man accused of murder in Detroit found significant errors in the forensic firearms testing used to connect bullets from the crime scene to his client. As a result of that revelation, the then-Chief of Police in Detroit requested an outside investigation by the Michigan State Police into the firearms and quality assurance units of the Detroit Police Department Forensic Services Laboratory. The report produced in that investigation, released in September 2008, found serious, widespread errors in firearms testing and laboratory procedure.

Investigators from the Michigan State Police re-examined over 200 instances of firearms analysis conducted by the DPD. Investigators found serious inconsistencies in 10% of these cases, indicating that forensic evidence in as many as one in ten firearms cases may have been compromised. The investigation also included a review of the laboratory’s procedures based on the national accreditation standards for forensic testing. Noting that “Essential criteria must show 100% compliance for accreditation to be achieved” by a crime lab, the investigation report into the DPD testing laboratory found that “the DPD firearms unit scored only 42% compliance with the Essential criteria.” The numerous procedural violations documented by the Michigan State Police investigators included a lack of proper labels on 90% of evidence jackets, without which “the chain of custody is broken and the integrity of the evidence is compromised.” Investigators also found that “access to the firearms unit is not restricted” and that there was no consistent documentation of “when evidence is removed from the firearms property room vault,” both of which also compromised the chain of custody on important samples of forensic evidence. Among the other violations listed in the report were a lack of proper training and assessment of technicians, widespread failures to properly calibrate and maintain testing equipment, and a lack of internal reviews or audits into the quality of work done at the facility. Taken together, these widespread failures were “so severe as to demonstrate a systemic problem in all disciplines in the crime lab,” according to a statement from Wayne County Prosecutor Kym Worthy made in the aftermath of the investigation. As a result of the audit by the Michigan State Police, the entire Detroit Police Department Forensic Services Laboratory was shut down in late 2008.

After the exposure of widespread problems in firearms testing by Detroit police, Darrell Siggers made contact with Claudia Whitman, an experienced activist and advocate working to exonerate victims of wrongful convictions. Whitman put Siggers in contact with a firearms expert who could review the statements of a Detroit forensic analyst who had testified against Siggers at his original trial in 1984. The analyst had testified that bullets recovered from the crime scene had matched bullets and shell casings found in the wood of the apartment across the hall from Siggers’ residence. A review of this testimony by the firearms expert working on Siggers’ case found that it was highly unlikely that an analyst would have been able to make a positive identification of the bullets identified at the two sites. Moreover, the expert pointed out that neither the bullets supposedly linking Siggers’ apartment to the crime scene nor the bullets taken from the crime scene itself had appeared in initial evidence reports. It was this evidence of false forensics testimony that finally led to Siggers’ legal exoneration in 2018.

Darrell Siggers was not the only exoneree in the 1974-1993 data set whose wrongful conviction was caused by a combination of witness intimidation and false forensic evidence.

Desmond Ricks was wrongfully convicted of second-degree murder in 1992, based on witness testimony and forensic evidence that purportedly linked the bullets used in the murder to a gun taken from Ricks’ family home. In 2010, Ricks, like Darrell Siggers, made contact with Claudia Whitman, who began working on his case. Soon thereafter Ricks reached out to the same firearms expert that had discovered the errors in the forensic analysis used to convict Siggers. That expert, a man named David Townshend, was himself a former Detroit police forensic analyst, and happened to have been one of the analysts who originally worked on Desmond Ricks’ case in 1992. Townshend told Ricks and Ricks’ legal team that he had initially had some concerns about the ballistic evidence from the crime scene. Townshend explained that the bullets that he had matched to the gun taken from Ricks’ residence had been in nearly pristine condition, not damaged as would be expected from fired ammunition. In 2015 Ricks’ legal team obtained photographs of the bullets taken from the 1992 crime scene. Upon examining these photos Townshend discovered that they were clearly damaged and not the same bullets that he had originally analyzed. The inconsistency led Townshend to conclude that investigators at the time of the murder had sent him bullets from the gun discovered at Ricks’ residence, not those taken from the crime scene.

It was not the only incident of blatant police misconduct discovered in the course of re-investigating the conviction of Desmond Ricks. In the mid-2010s members of Ricks’ investigative team produced a statement from one of the primary witnesses, a woman named Arlene Strong who had testified against Ricks at his original trial. Strong recanted her initial testimony in which she had stated that the weapon she had seen used in the murder looked like the gun taken from Ricks’ family home. Just like the allegations against police intimidation of witnesses during their investigation of Darrell Siggers, Arlene Strong claimed that officers had threatened to have her arrested if she did not change her statement to affirm that the weapon from Ricks’ residence was the one she had seen at the crime scene.

In 2017, the totality of police misconduct in Desmond Ricks’ case led Wayne County prosecutors to join a motion requesting a judge to vacate Ricks’ conviction. The motion was granted and Ricks was promptly released from prison. In total, Ricks spent 25 years wrongfully incarcerated.

Taken together, the cases of Desmond Ricks and Darrell Siggers paint a picture of what can happen when a callous police culture is coupled with a systemic lack of procedure and accountability. Police in both cases displayed reckless disregard for the truth in the investigations they were charged with carrying out. Not only did investigators in both cases ignore the statements of witnesses when they seemed to point to the innocence of their prefered suspects, they actively used intimidation and threats of arrest to compel those witnesses to change their statements and lie under oath in order to obtain dubious convictions. The extreme faults and lack of properly implemented procedures in Detroit’s forensic crime lab, exposed by state investigators in 2008, facilitated police misconduct and wrongful convictions. The lack of procedural safeguards for protecting the chain of custody of important pieces of forensic evidence seems to have opened the door for police to falsify forensic material, as occurred with the bullets used to link Desmond Ricks to the 1992 murder for which he was convicted. Similarly, an absence of sufficient technician training and review standards likely played a role in the false forensic conclusions reached by an analyst in Darrell Siggers’ case.

The wrongful convictions of Desmond Ricks and Darrell Siggers also suggest that these problems were both systemic in origin and long term in duration. Siggers was convicted in 1984, Ricks was convicted in 1992, and the Detroit Forensic Services Laboratory was shut down in 2008. These facts, coupled with several other exoneration cases during this period that involved similar types of police misconduct and false forensic conclusions show that these problems persisted within the Detroit Police Department for at least 24 years. Even if operating under the assumption that police intimidation of witnesses and falsification of evidence was limited to certain individual officers, as opposed to being the product of a broader police culture, it remains clear that the misconduct of those “bad apples” was enabled and actively facilitated by a systemic lack of procedure and accountability. There can be little doubt that those individuals already exonerated represent the full extent of the wrongful convictions caused by these systemic problems. It is unlikely that we will ever know the totality of the harm caused by the faulty investigations carried out by officials in the Detroit Police Department.

Sources:

Detroit News

Detroit Free Press

Michigan State Police Forensic Science Division, "Detroit Police Department Firearms Unit Preliminary Audit Findings," Sept. 23, 2008.

National Registry of Exonerations, Newkirk Center for Science & Society at University of California Irvine, the University of Michigan Law School and Michigan State University College of Law, https://www.law.umich.edu/special/exoneration/Pages/about.aspx.

Voice of Detroit